Democracy and the Military

One of the most dramatic developments in Latin America today is the unprecedented shift in the nature of politics since the late 1970s. At no time in the history of the Latin American republics have so many countries established and sustained electoral democracies without military takeovers.

The military coup is no longer an alternative mechanism for acceding to power in the region. There were 19 successful coups in the 1960s in Latin America and 18 in the 1970s, but just seven in the 1980s and only two in the 1990s. The two coups thus far in the new century lasted just hours, both aborted by intense international pressure.

Within a single political generation, electoral democracy has become the norm in almost all of the 20 Latin American nations, imperfect and facing multiple challenges, to be sure, but seen as legitimate by most citizens everywhere in the region. One noteworthy change is the unprecedented willingness of the military in recent years to remain on the political sidelines in Latin America. How can this extraordinary development be explained?

One answer may be found in the failure by the Latin American militaries, that took power throughout the region during the so-called “Third Wave” of authoritarianism between the 1960s and the 1980s, to accomplish their political and economic objectives. The long-term institutionalized military regimes in place in many Latin American countries during these years found that it was much harder to implement policies than to make plans. Chastened by their experience as well as weakened and divided, most were only too glad to return to the barracks—and stay there. The end of the Cold War certainly has contributed to this process.

Another is the combination of the debt crisis of the 1980s and the “lost decade” of national economic erosion that weakened the military institutions through reduced budgets and training. The economic crisis forced them to reassess their historic roles and missions.

From such a reassessment, many Latin American armed forces began to take on a new mission—international peacekeeper. Military and police contingents from 13 countries were serving in the 22 United Nations peacekeeping and other operations in place in 2000. Among the most active were Argentina and Uruguay, with 12, Bolivia and Chile, with six, El Salvador with four, and Brazil and Peru, with three. Such missions can only serve to enhance the professional stature of the armed forces and help to justify their continued relevance in the post-Cold War era.

With the establishment of inclusive mass democracy during a period of economic distress, civilian authorities faced a “guns OR butter” situation. They were under great pressure to increase social expenditures, often at the militaries’ expense, thus further weakening the institutional capacity of the armed forces. While the military establishments were not bereft, many were not able to modernize.

The terms of negotiation for the transition from military to civilian rule in several cases served to protect armed forces interests within civilian rule. In Chile and Ecuador, the military retained a guaranteed share of copper and oil revenues. In Brazil, the military tinkered with the electoral mechanisms until it found a formula that provided relative assurance of moderate civilian rule. Chile’s military leaders also adjusted electoral provisions to assure selection of sufficient conservative senators to block constitutional change and formed a National Security Board that their members dominated and that was not accountable to civilian authority. In Uruguay, the military protected itself from prosecution for abuses while in power through legal provisions proscribing such initiatives under civilian rule.

Short of military takeovers, the armed forces also influenced politics by building alliances with civilians and influencing politics from within. One example is Peru’s use of the principle of civilian control in the 1990s to protect military interests and preserve its privileges.

Haiti and Panama serve to illustrate how egregious military abuse in power can lead to outside intervention and the decision to abolish the military altogether. Such initiatives reinforced a parallel campaign by Nobel Peace Prize recipient Oscar Arias to apply the Costa Rican model of a political system without a military establishment to other smaller countries of the region.

In combination, these explanations suggest an emerging new dynamic of civil-military relations in Latin America in which the armed forces are coming to accept a different role from that which has prevailed in the region since independence.

The changes over time in patterns of military expenditures within Latin America are also revealing. While many changes within individual countries respond to local or sub-regional security issues, the consistent overall pattern over the decades has been a progressive reduction in the burden of military expenditures as a proportion of central government budgets. These have declined from about 21% in the early 1920s, 19% around 1940, 15% as of 1960, 12% in 1970, and 11% about 1980. The only broad exception to this trend is the 1980s, when overall military expenditures increased by over 40%, largely to develop counterinsurgency and counter-drug capacities, before dropping back to about 10% in 1993 and 9% in 1997. Data for 2000 suggest that this trend is continuing—eight of the 20 Latin American countries reduced their military budgets between 1997 and 2000, three remained about the same, and nine increased.

These recent expenditure patterns, including both police and military, suggest that the armed forces of Latin America no longer in most cases consume a disproportionate share of the budget (Chile, at 17.8% in 1997, Colombia with 19.9%, and Ecuador at 20.3%, are the major exceptions.). This trend appears to suggest one of the beneficial effects of democratic practices and civilian control.

Continued expansion of democratic practice and its gradual consolidation get a significant boost from the unprecedented change in the regional and international context of international agreements. These include the Santiago Accords of 1991 Organization of American States (OAS) Resolution 1080, the OAS Washington Resolution of 1997, and the Democratic Charter of Lima of 2001. By signing these multilateral accords, Latin American governments have agreed to give up their long-standing principle of non-intervention. They now allow a regional body to determine appropriate measures when democracy is threatened in a member state. The OAS has invoked one or another of these provisions to respond to internal political crises in various member countries, including Haiti, Peru, Guatemala, and Paraguay. Furthermore, the mere presence of these multilateral instruments has also served as a further stimulus for political elites to work out their problems without threatening democratic forms.

The rapid proliferation of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), both national and international, has also contributed to the consolidation of democratic procedures. These groups have worked to protect, preserve, and expand democratic procedures and practices by calling attention to abuses, protecting human rights, overseeing elections, and generally reinforcing civilian actors and civil society. They include civil-military groups and associations of representatives from both sectors that meet regularly to work through issues and foster mutual understanding. NGO presence and advocacyhelps to further legitimate the democratic process and to make government organizations and procedures, including those of the military, more open and transparent.

While civilian democratic rule now prevails almost everywhere in Latin America, specific cases illustrate some of the challenges that individual countries continue to face.

In Venezuela, the election of a military leader associated with a violent failed coup, Hugo Chávez Frias, introduced a new pattern of military institutional involvement in activities historically carried out by civilian or police authorities—such as crowd control, citizen mobilization, and public works. The creation of popular militias, the so-called Bolivarian Circles, is also a distressing development. Chávez and the military have filled the political space left by the progressive discrediting of once robust political parties. In Venezuela, the electoral process rather than the coup has reintroduced the military into politics, posing a new type of threat to the principle of civilian authority.

The case of Peru reveals a second troubling pattern of civil-military relations. This is the systematic abuse by an elected government of democratic procedures and civilian as well as military organizations to ensure continuation in power. Abuses included a unilateral amnesty for the military and police for human rights violations, the thwarting of a referendum on an unconstitutional third successive election of the president, the stacking of judicial and electoral bodies with government loyalists, and the use of computer machinations to change the presidential vote count. The civilian regime also resorted to massive bribery to ensure a congressional majority and manipulated military and police appointments to ensure compliant armed forces and an intelligence service that would serve the government by intimidating the opposition.

Through such measures, the institutional integrity of the military was severely compromised in ways that contributed to its dramatic failure to dislodge Ecuador’s forces in the 1995 border war. The intelligence services were also adversely affected. Consumed by tracking the legal opposition, they failed to prevent the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA) takeover of the Japanese Ambassador’s residence for four months in 1996-97.

Civilian democratic forces regained the upper hand in the dramatic political denouement of late 2000 and brought about the removal of the “elected” regime and the arrest of scores of corrupt politicians, military, and police. However, the damage done to the political and security institutions of Peru will take years to overcome.

Ecuador’s recent experience suggests a third pattern. Successive elected presidents were removed by congress and a brief civil-military takeover that only international pressure kept from becoming the first successful coup of the 21st century in Latin America. Ecuador provides an example of sustained electoral democracy, but with a multiplicity of parties and procedural regulations that virtually ensure political immobility in combination with a strong armed forces fresh from the military success of the border conflict with Peru. While civilian rule was quickly restored in 2000, a well-institutionalized military establishment remains a political alternative should the civilians falter again. The weight of OAS, United States, and European Union sanctions is the major force standing in the way of any unconstitutional takeover by the military in Ecuador.

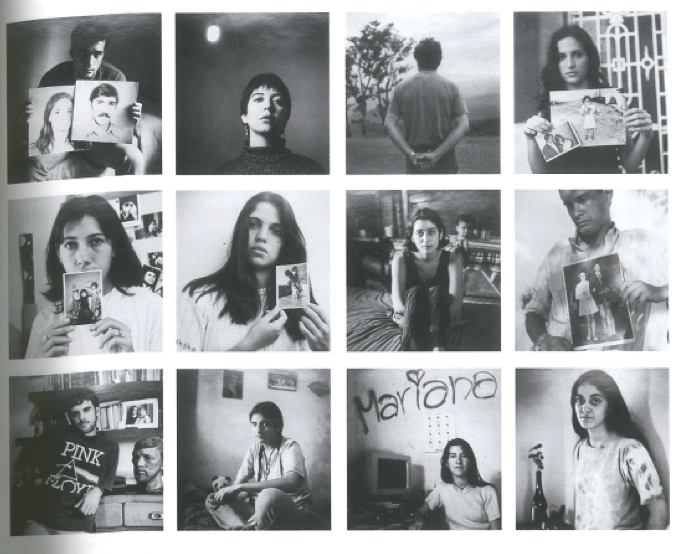

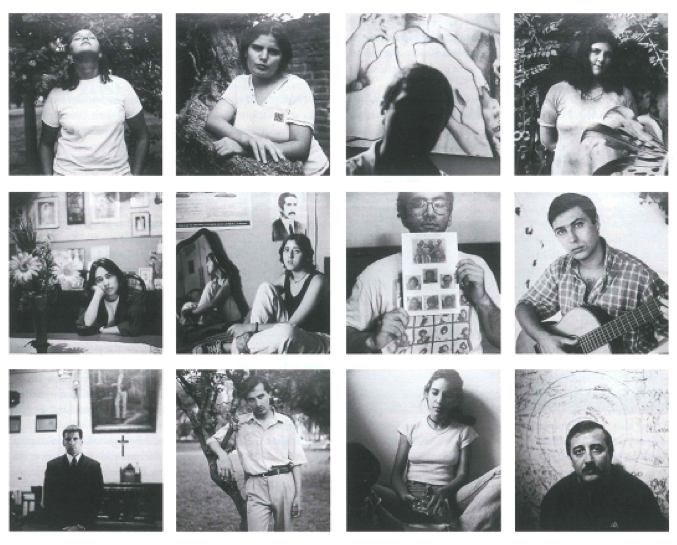

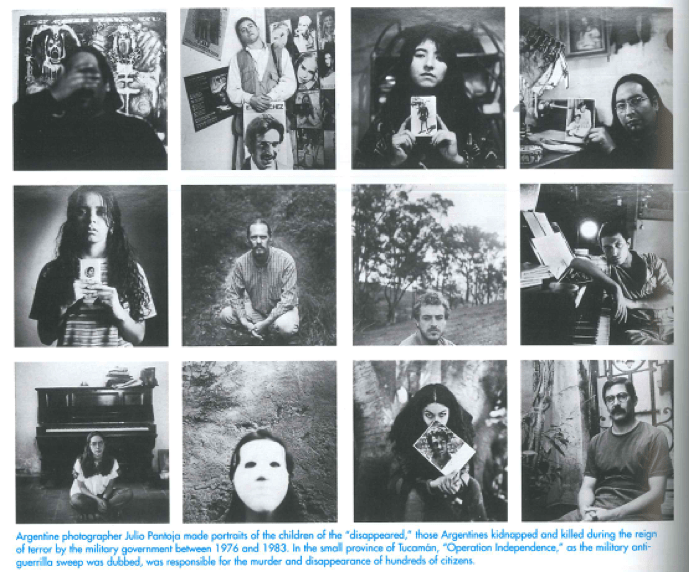

Argentina’s sad tale may be the limiting case in civil-military relations. Here the economic crisis of late 2001 and early 2002 led to the president’s resignation and a revolving door of short-term heads of state, with early elections now in the offing. Throughout the crisis the Argentine military, dramatically downsized by elected governments after its debacle in the Malvinas war and its gross mismanagement and human rights abuses while in power between 1976 and 1983, played no role. Here the civilian authorities were forced to try to work out alone some solution to their country’s problems that appear to be resolvable only with some accommodation with the international financial community.

Colombia, formally democratic since the late 1950s, reflects a progressive erosion of central government capacity in the face of economic stagnation, major drug production, the breakdown of personal security, and generalized political violence. In this context, the armed forces became less able over time to carry out its basic mission of protecting the population and the government. Plan Colombia was designed to reverse this trend by providing substantial economic and military assistance to enable the military to increase its capacity to better protect a beleaguered civilian government.

While many of Plan Colombia’s provisions are controversial, the resources provided appear to be in the process of accomplishing their goal. The military is now larger and better prepared. Formal democracy continues, though with the recent election of a hard-liner with a mandate to restore peace through military initiatives. In Colombia democracy is trying to survive, and the military at this point is committed to its protection. There is no question in the Colombian case of a military takeover, but concerns remain over the likely dynamics of a military-led initiative to end the violence rather than peace negotiations.

As these specific examples suggest, on balance Latin American democracies remain troubled, but in place. The dynamics of civil-military relations vary widely from country to country, but overall the trend continues toward the continued prevalence of civilian-led government and democratic procedures. In most countries, the military has accepted its role as subordinate to civilian authority and is working to redefine its mission within that context. The financial woes of the 1980s and the market liberalization initiatives of the 1990s continue to limit the ability of most armed forces to retain the strong institutional capacity that they developed in earlier decades, with attendant effects on their commitment to professionalism. While this could pose a danger for democracy at some point, the regional and international consensus on the value of civilian elected government offsets such tendencies.

Nevertheless, the armed forces of the region continue to have several important roles to fulfill. One is the new focus on international peacekeeping. Another is the protection of borders still in dispute, both land and sea. In addition, natural disasters require the military to take on emergency rescue and civilian support tasks. Finally, counter-drug operations require armed forces initiatives. As a result, military establishments of the region can continue to justify their presence and their significance without recourse to coups. Democracy in Latin America has multiple challenges to overcome, but in most countries the threat of a military takeover is not one of them.

Fall 2002

David Scott Palmer teaches Latin American politics and United States-Latin American relations at Boston University. His recent writings include “The Military in Latin America,” in Jack Hopkins, ed. Latin America: Perspectives on a Region, 2nd edition (1998), and, with Carmen Rosa Balbi, “‘Reinventing’ Democracy in Peru,” Current History (February 2001).

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Democracy

Ellen Schneider’s description of Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega in her provocative article on Nicaraguan democracy sent me scurrying to my oversized scrapbooks of newspaper articles. I wanted to show her that rather than being perceived as a caudillo

Battro Named to Pontifical Academy

Antonio M. Battro M.D., Ph.D. has been named to The Pontifical Academy of Sciences, the oldest science academy in the world, established by Galileo 400 years ago. Battro, Robert F. Kennedy…

Entre los panales y el poder

Cuando Jacqueline van Rysselberghe fue informada en Noviembre último que ella debería dejar su puesto como alcaldesa de Concepción, una de las ciudades mas grandes e…