Displacement on the Border

The Tale of Guadalupe

GUADALUPE, Chihuahua — A shadowy mix of actors preparing for the start of oil and gas production has spurred large-scale land displacement here, allege hundreds of current and former residents and former residents of the Valley of Juárez. The case has spawned mass applications for political asylum in the United States. The Valley of Juárez hugs the United States-Mexico border southeast of Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua and El Paso, Texas. Though the area is known principally for agriculture, Mexico’s state-owned energy agency Pemex has drilled exploratory wells in the region, and pipelines, a major highway and other infrastructure to support energy production are either planned or under construction. Several valley towns are now near empty, including Guadalupe, where the Mexican army now patrols a practically abandoned town.

The story is unfolding as the city of Juárez actively promotes tourism, celebrating crime rates that have declined since the zenith of a drug war in 2010 and accomplishments such as hosting Pope Francis in February 2016. In a bilateral nod to the valley’s economic promise, a state-of-the-art border crossing linking Guadalupe with Tornillo, Texas, was inaugurated by Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto and U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson in 2016.

Real estate in this sepia-toned, hardscrabble slice of the borderlands has become valuable. The valley is littered with stories about terrorized people fleeing. Guadalupe is eight miles by curving road from the U.S. border across from Tornillo, Texas, but a world away in terms of security. According to the Mexican census, nearly 10,000 people lived here in 2005. By 2010, that figure had fallen to approximately 6,500. Guadalupe’s mayor, who declined to be interviewed for this story, claimed in local media that approximately 1,000 residents remain in 2016.

Physical evidence in Guadalupe suggests that someone doesn’t want people here. Charred or completely burnt houses and shuttered stores line the streets. Pockmarked and shattered windows are everywhere. Very few people are out walking or driving.

“The government sends people here to pressure landowners to get out of here, to say, ‘Go away, we don’t want you here,’” said one resident of Guadalupe who, like others here, asked not to be identified for fear of retribution. Chihuahua’s government denied that allegation.

Analysts suggest buyers are arriving because the area shares geological characteristics with the Permian Basin of Texas and New Mexico, the highest-producing oil field in the United States. “Obviously this land is being re-consolidated in the hands of a few, ” said Tony Payan, director of Rice University’s Mexico Center in Houston. “Many of these politicians will have interests in the shale development in the future and will likely get ahold of that land no matter what.”

The government’s narrative is that Mexican soldiers were sent here to root out organized crime in a prime smuggling corridor to the United States and that the violence is generated by competing cartels. But residents said they believe soldiers are working with organized crime, charging that no activity, legal or otherwise, takes place without tacit government sanction. “This valley is a lawless place, ” another man stated. “It’s the sad truth. ” And when landowners leave and default on property taxes, the state can legally seize their land. After that, the government can legally sell the land to private interests.

Mexican authorities cited in media reports say at least three hundred people have been killed in Guadalupe since 2008—mayors, police, city councilors, business owners and human rights activists. People are learning hard lessons about real estate.

“You know the rule. Location, location, location,” said Julián Cardona, a Mexican photographer based in Ciudad Juárez. He described a slow-motion depopulation that’s taken place over the course of several years. “Every time there was a killing, every time there was a burning house, residents said the soldiers were a block away, ” Cardona recalled. “The soldiers didn’t stop the killers or the people burning the houses.” Others recount soldiers searching homes, purportedly for weapons, followed by the arrival of masked gunmen who then kill or terrorize members of the household.

Pipeline companies in Texas are historically granted the right of eminent domain, the legal right to seize private land because the transport of energy is deemed to be in the public interest. “In the United States, it’s a lawful eminent domain. In Mexico it’s outright violence, ” said El Paso lawyer Carlos Spector. He represents approximately 600 former residents of Guadalupe now seeking asylum in the United States.

“Investors are getting very aggressive, ” said Spector. “All they have to do is get a list from the mayor of a small town, who is under their control, as to who hasn’t paid the taxes. And if they can match up who hasn’t paid the taxes to where the gas and the freeway is coming, then you go after that property. It’s very, very scientific.”

People who remain in Guadalupe say former neighbors who have fled are frantically trying to sell their now-abandoned land though middlemen for cents on the dollar because they’re too frightened to even contemplate coming back.

FEAR IN THE JUÁREZ VALLEY: A CASE STUDY

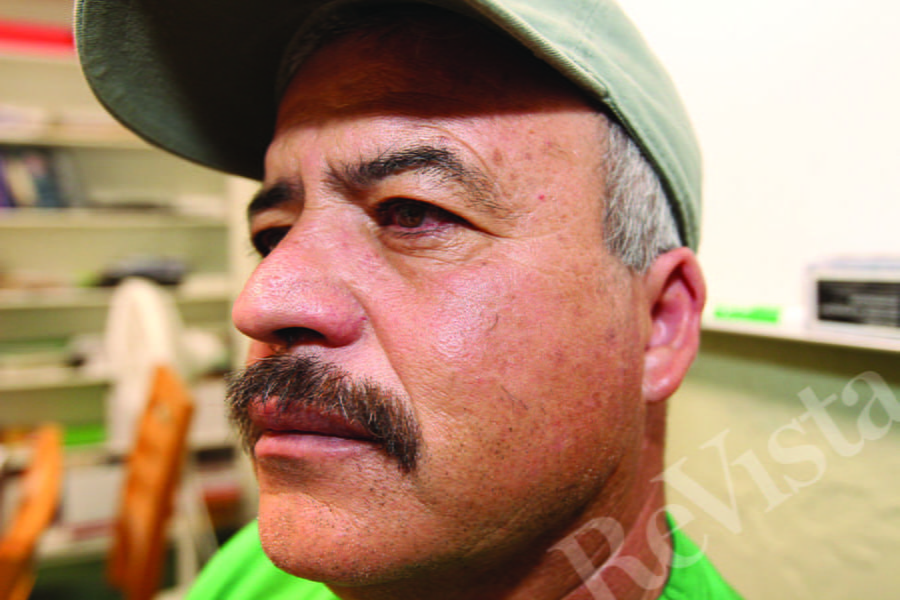

Martín Huéramo, a former city councilor in Guadalupe now seeking asylum in the United States, told me in El Paso that he had received several threats.

Huéramo had opposed the mayor’s resolution that would allow the local government— rather than the state or federal government— to expropriate land to sell to energy speculators. The week after Huéramo was granted permission to enter the United States pending his asylum application, two women on the city council were killed. They had opposed the same resolution.

The year before, he told me two of his brothers-in-law were murdered. “Families in the Valley of Juárez have lost loved ones, ” he said. “It’s a message saying they have to leave. ”

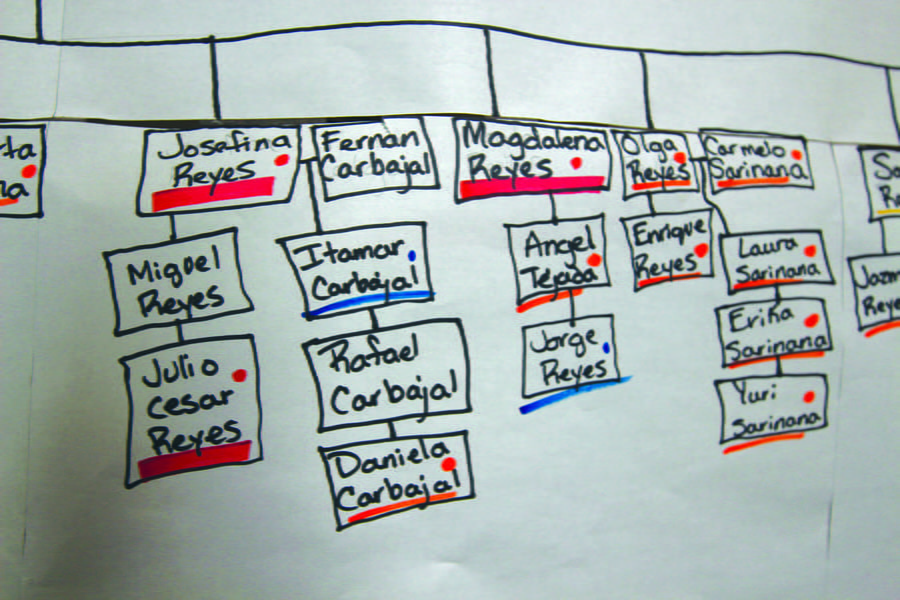

Residents say the murder of human rights activist Josefina Reyes Salazar in 2010 made the valley feel even more dangerous. She was shot to death by a masked gunman soon after she claimed the military was involved in the killing of her son. Reyes Salazar’s brother, sister and a sister-in-law were murdered the next year. In total, six members of the family have been killed.

Gabriela Carballo, an art gallery administrator from Ciudad Juárez, compared opposition to pipelines in Guadalupe to the opposition by some Texas landowners and ranchers to the Trans Pecos Pipeline that will ferry natural gas from Texas into Mexico .

“As a Mexican I can say that we care as much about the environment as any one of these people that are fighting the Trans Pecos Pipeline, ” said Carballo. But she said it’s difficult to take a stand under the actual or perceived threat of retribution. “If we speak out against it, we run the risk of our really extremely corrupt government murdering us,” she said.

There’s no way to verify such a claim. And Mexican officials are quick to refute them. “Violence is minimal right now and no one’s been affected by plans for pipelines, ” said Arturo Llamas, a regulator of pipelines and energy infrastructure in Chihuahua. Llamas, who is also the state’s liaison with Mexico’s federal energy agencies, said energy development in northern Chihuahua represented a boon for valley residents that will ultimately translate into lower electricity and gasoline costs.

“It will help the entire country, not just Chihuahua, ” he said. He claimed to be focused on the valley. “It’s our responsibility to be sure laws are obeyed and that everything that must be done is done properly,” he said. He said he wanted anyone with a complaint to contact his office in Chihuahua City. But few people alleging harm are likely to approach a government they don’t trust.

“I think they [the residents] are now realizing the value of their land,” said Cardona, the Mexican photographer. “Violence is linked to displacement of their families.”

Cardona recalled a visit June 24, 2015, when former Chihuahua Governor César Duarte made a brief stop in Guadalupe. “The governor visited Guadalupe and the mayor ordered the empty buildings and house along the main avenue painted in bright colors; glowing yellow, green, blue, pink. The fact the houses were painted in bright colors is like a smokescreen of what’s really going on, ” Cardona said.

As for Martin Huéramo, the former Guadalupe city councilor seeking asylum, he said he would have no issue with energy production or pipelines if they did not involve, in his words, people being forced out. He doesn’t believe government claims that laws are being adhered to.

Then unexpectedly, he said he believed one of the government’s claims. “The government says violence is down in the Valley of Juárez.” he said. “I believe it because there are no more people left to kill.”

Winter 2017, Volume XVI, Number 2

Lorne Matalon is the 2016-2017 Energy Journalism Fellow at the University of Texas at Austin. He is a staff reporter at the Fronteras Desk, a collaboration of National Public Radio stations focused on Mexico and Latin America.

Related Articles

Colombia’s Other Displacements

Of course, I knew about Colombia’s sad statistics on displacement, with the highest numbers in Latin America and vying with those of war-torn countries like Sudan and…

Getting Respect

When I first arrived in Brazil in the 1980s, I quickly learned that race in Brazil was not important there. The country that once had by far the largest slave population in the…

Ana Tijoux’s Radical Crossing of Borders

This summer, I was an intern in Santiago’s Museum of Memory and Human Rights, the museum dedicated to the victims of Pinochet’s dictatorship. Since I was in Chile…