A Review of Doña Lucía: La Biografía no Autorizada

For the Love of Lucy

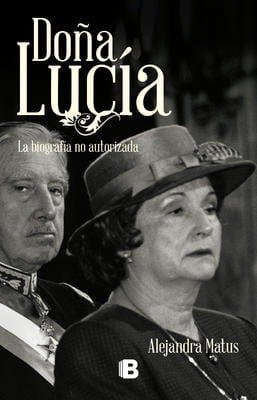

Doña Lucía: La Biografía no Autorizada By Alejandra Matus Santiago de Chile: Ediciones B, 2013, 279 pages.

The day Lucía Hiriart returned to her native Chile from Ecuador in 1959 was not a happy one. With five young children in tow, she and her husband Augusto Pinochet had just spent three and a half years on assignment in Quito, while Augusto, a young Army captain, served as an instructor in the newly founded War Academy in that country. The mission was seen as a promotion for the career officer, who was struggling to advance in the ranks while raising a family. His wife’s parents had little affection for a person they deemed beneath their daughter. Not only was he eight years her senior but also a man of arms in a society deeply suspicious of the military. Yet the marriage somehow endured. Quito, however, proved disastrous for the young couple. Pinochet pursued an active social life while his wife remained at home with the children. Such was the allure of his new job—and a much appreciated salary in U.S. dollars—that he eventually broke his marital vows and pursued other women until his wife threatened to denounce him before his superiors. Knowing that unmarried or separated men (Chile had no divorce until 2004) had little chance of promotion within the Chilean military, she was able to reign in her husband’s philandering, but the marriage had noticeably soured. In every subsequent fight whenever angered, she would unleash her festering resentment for the indignities she had suffered by calling the man who would come to brutally rule Chile by a simple phrase: “milico de mierda.”

Doña Lucía: La Biografía No Autorizada is Alejandra Matus’ effort to show Lucía Hiriart, a controversial yet cultured woman who ruled Chile alongside her husband with scorn for her adversaries, in a new light. Obsessed with virtuosity, piety and good manners, “Lucy” as she was called by friends, was much more instrumental in driving her husband to the edge than previously believed, based on documents and interviews with witnesses and relatives. “I never thought that the plump nice lady of the first days in power would reveal herself to have such a mean character,” said a former government official. Some saw her as Pinochet’s personal right wing, even forcing her husband to break with protocol in public events to greet her first as Head of the Feminine Organizations before any other member of the ruling Junta. “This is war,” she would declare, “and everything is permitted. Had it not been them, it would have been us.” Lucía was especially cruel to those she knew. Anyone who crossed either of them would receive no sympathy.

Matus, a 2010 Nieman Fellow at Harvard, is a well-respected Chilean journalist with many notable books to her credit. Chief among them is El Libro Negro de la Justicia Chilena (2009)—banned right after publication—that focused on the shady dealings of the Chilean judiciary. Servando Jordán, the Supreme Court Minister who invoked a state security law to forbid the book from circulation, accused the author of slander and contempt of court. In response Matus sought refuge in the United States where she was granted political asylum. Two years later the Chilean Congress approved a new law on the press in 2011, allowing the author and the book to circulate freely in Chile.

Doña Lucía has seven chapters that follow a chronology of the Pinochet-Hiriart marriage and discloses little known details about the couple and their disagreements. Perhaps the most revealing is the intimate tension besieging the underachieving husband and the overambitious wife throughout their lives. She hailed from a prestigious family of lawyers and politicians, was raised in an elite school, the daughter of a senator, while he was merely the son of a customs officer and a housewife, and had barely managed admission to the Military Academy on his third try. Augusto had married up, was content with earning a salary in uniform, and was well aware that climbing the ranks beyond colonel would be difficult for an infantryman. Lucía, however, wanted more. She had overcome her parents’ reservation about her choice of husband but only for the opportunity to achieve glory and fame, and if her husband was slow to pursue the perks of power, she would be right there to whip his insecurities into obedience for the sake of her ambition.

The author depicts Augusto as indecisive but astute in the days leading to the rebellion against President Salvador Allende, unsure of the final outcome but swift to eliminate any opposition to his leadership as events unfolded. From Matus’ account, it is Lucía who emerges as the influential partner in defining a new attitude after the military coup of September 11, 1973. Women were destined to heal the nation and assist in its reconstruction, she insisted, and she would lead the charge in that direction by becoming the beacon for morality and discipline. She seemed oblivious to her family’s own extravagances. No man or woman in the military or government who abandoned his marital duties—or imperiled those of others—would remain unpunished. For that she needed access to the best intelligence she could get. Everyone would be accountable to her. To make sure that got done and to prevent other women from approaching her now powerful husband, she forged a close relationship with Colonel Manuel Contreras Sepúlveda, the nefarious head of the División de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA), the secret police. Contreras became a powerful ally while she kept the other military wives of the Junta at bay. She was to preside over all of them—as her husband’s army branch was to prevail in protocol over all military branches. Knowing full well that a place in doña Lucía’s heart (and fears) was the best life insurance for the ambitious spymaster, Contreras encouraged her paranoia with conspiracies large and small that only he could unravel. For his loyal service he was never to lose her trust.

The book reveals in detail how Lucía used the CEMA foundation to expand her reach in public affairs. She had been appointed head of this organization that cared for women and children, but she looked beyond its boundaries to exert more influence in other matters. Rules were modified or eliminated to accommodate her demands for protagonism. She traveled, served her husband’s government as an arbiter of good taste and even fantasized of becoming a Chilean Eva Perón. “She was active and efficient,” claimed an insider, “but also impulsive and demanding. No one would overshadow her for fear of provoking her wrath.” Others disagreed with this assessment stating that Pinochet simply used Lucía to accomplish objectives of his own while leading her to believe that he was acting at her behest. He was quoted as saying that “one may yield on tactics but never on strategy.”

For historians, the book offers a complementary look at the intimate life of the family who ruled Chile’s dictatorship during its most calamitous period. It gives them and the general readers important insights into the personal tensions that drove Augusto and Lucía as they ascended to power while trying to control a progeny that had ambitions of its own. But their moment of personal glory was not interminable. Although they were able to amass a considerable fortune at the expense of the country, they also endured the humiliation of being arrested while visiting a foreign country, and the humiliation of seeing everything they had built come tumbling down. Lucía survived her husband’s passing in 2006 only to witness her influence and fortune taken away by the government, revealing her own corruption in the process. A sad spectacle a whole country has had to endure in the pursuit of justice.

Spring 2015, Volume XIV, Number 3

Pedro Reina Pérez, a historian, journalist and blogger, was the 2013-14 DRCLAS Wilbur Marvin Visiting Scholar. He is a professor of Humanities and Cultural Agency and Administration at the University of Puerto Rico. Among his books and edited volumes are Compañeras la voz levantemos (2015), Poeta del Paisaje (2014) and La Semilla Que Sembramos (2003). More at www.pedroreinaperez.com

Related Articles

A Review of Authoritarian Consolidation in Times of Crisis: Venezuela under Nicolás Maduro

What happened to the exemplary democracy that characterized Venezuelan democracy from the late 1950s until the turn of the century? Once, Venezuela stood as a model of two-party competition in Latin America, devoted to civil rights and the rule of law. Even Hugo Chávez, Venezuela’s charismatic leader who arguably buried the country’s liberal democracy, sought not to destroy democracy, but to create a new “participatory” democracy, purportedly with even more citizen involvement. Yet, Nicolás Maduro, who assumed the presidency after Chávez’ death in 2013, leads a blatantly authoritarian regime, desperate to retain power.

A Review of Las Luchas por la Memoria: Contra las Violencias en México

Over the past two decades, human rights activists have created multiple sites to mark the death and disappearance of thousands in Mexico’s ongoing “war on drugs.” On January 11, 2014, I observed the creation of a major one in my hometown of Monterrey, Mexico. The date marked the third anniversary of the forced disappearance of college student Roy Rivera Hidalgo. His mother, Leticia Hidalgo, stood alongside other families of the disappeared organized as FUNDENL in a plaza close to the governor’s office. At dusk, she firmly read a collective letter that would become engraved in a plaque on site. “We have decided to take this plaza to remind the government of the urgency with which it should act.”

A Review of A Promising Past: Remodeling Fictions in Parque Central, Caracas

A beacon of modern urban transformation and a laboratory of social reproduction, Parque Central in Caracas is a monumental enclave of 20th-century Venezuelan oil-fueled progress. The monumental urban structure also symbolizes the enduring architectural struggle against entropy, acute in a country where the state routinely neglects its role in providing sustained infrastructural maintenance and social care. Like other ambitious modernizing projects of the Venezuelan petrostate, Parque Central’s modernity was doomed due to the state’s dependence on the global oil economy’s cycles of boom and bust.