DRAGONS ON THE LANDSCAPE

Endemic Fauna & Forms of Volcanic Governance

“Dragons on the landscape”. Maribios Volcanic Range from the Pacific coast of Nicaragua. Colored photomontage by Oscar M Caballero.

In the Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican territory, animals had a cultural role beyond agriculture and farming. Indigenous people would express their appreciation of animals with powerful and divine qualities such as jaguars, panthers, snakes and mesmerizing birds through pictorial elements, paraphernalia and the crafting of mythological literature. Native fauna was often painted, carved and even sculpted on mediums of architectural character such as stone trails, cave walls and, later, buildings. These practices developed a profound connection between memory and architecture that has prevailed until the present day. The landscape animal presence would trigger legends about lagoons and volcanic mythology, the naming of regions and religious beliefs. Nevertheless, during the colonization period, the European cosmovision regarded the native culture as pagan mythical folklore.

The colonial mestizaje blended the new Catholic rituals with indigenous practices in a slow amalgamation of customs, often featuring animals in a new way. For example, the satirical drama “El Güegüense o Macho Ratón,” proclaimed by UNESCO as a masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, revolves around encounters between Spanish authorities who wear masks with Caucasian features and Native people who wear horse masks. The Indigenous dancers maneuver clever ways to challenge the colonial authority. The use of a horse mask represents a metaphorical abstraction of wild horses that resist captivity.

A Liquid Country

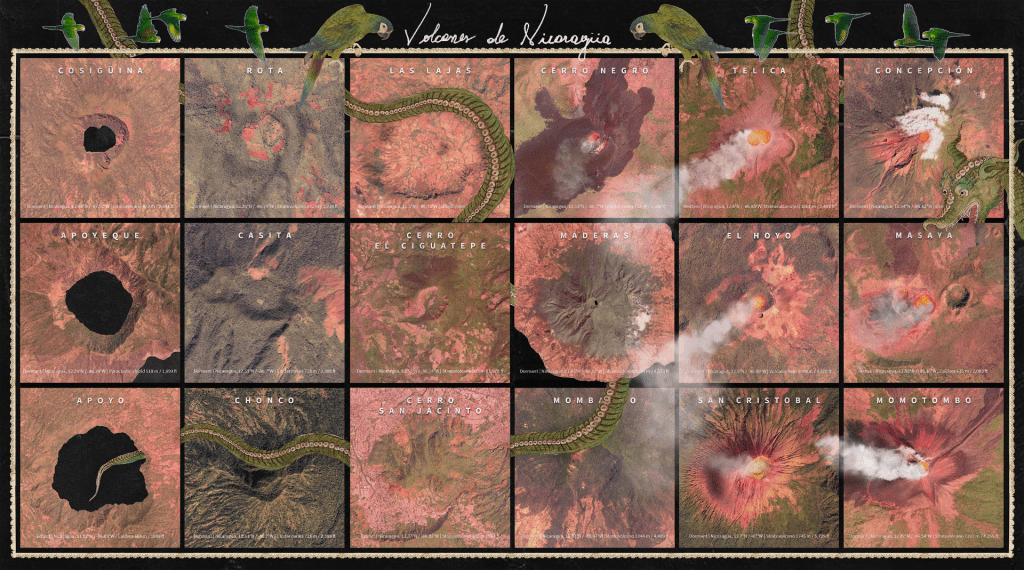

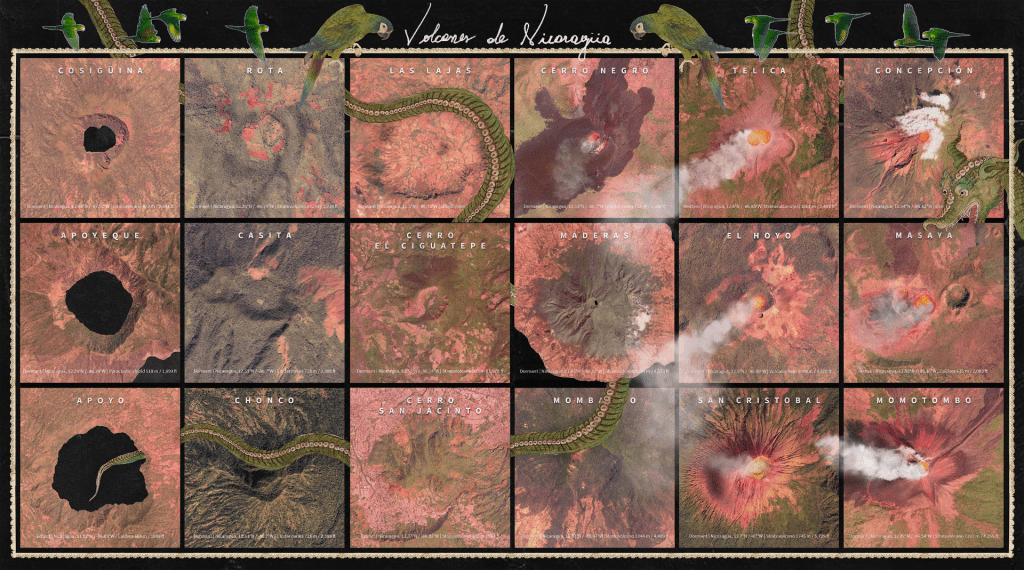

“Tierra de fuego”. Catalog of Nicaraguan volcanos. Colored photomontage by Oscar M Caballero.

Countries with high volcanic activity such as Nicaragua are constantly in flux. The geological movement triggers motions of geographic, political, urban and architectural collapse. This cycle of territorial renewal maintains an intriguing ephemeral state on the landscape. In his foreword to Sabrina Duque’s VolcáNica: Crónicas de un país en erupción, Nicaraguan writer Sergio Ramírez describes the nation as a territory that is yet to be geologically transformed. He establishes a parallelism between geography and history, by virtue of the seismic affairs that shake the underground realm and the political revolutions on the surface that have caused a different type of turmoil, both with dreadful consequences. One could perceive Nicaraguan geography as a liquid state of temporary permanence driven by its volcanology to influence politics, urban planning and nature’s evolutions. This territorial liquidity also carries along traces of memory, storytelling and forms of enduring.

The post-volcanic landscape has proven to be an incubator for fascinating natural transformations that redefine human and non-human boundaries. From the emergence of new ojos de agua out of emptied volcanic craters, the birth of islands on water bodies that were originally part of volcanic erupted material, unexpected forests from fertile post-volcanic soil, topographic transformation at a city scale, urban settlements and nationwide displacements and mutation of animal and plant species.

“Huellas de Acahualinca Maquette”. Photo from the Acahualinca museum in Managua, Nicaragua.

The oldest traces of the presence of animals living among the Nicaraguan people were imprinted about 6,000 years ago by an opossum, a bird and a deer on volcanic mud. The Acahualinca footprints were discovered by accident in 1874 in the capital Managua near Lake Xolotlán. During decades of archaeological studies, it has been determined that 18 people divided into two groups of men, women and children were walking away from a volcanic eruption. In between the two days’ journey, the group of animals passed through the night following the same instinct on a trajectory towards the lake. The fluid lava would solidify these ancient tracks and influence the beginning of a new human settlement that would focus on fishing and agriculture. In modern times, the lake was contaminated by decades of urban mismanagement. Environmental experts think that the mercury ingested in fish such as guapote, mojarras and guabinas would have a negative long-term effect on consumers.

The contamination of Lake Xolotlán is not an isolated case. Multiple water bodies in Nicaragua with rare natural characteristics have been jeopardized through waste modes ranging from an institutional to a local level. Animal and plant species have been the first to perish or emigrate to safe locations. Protecting certain regions as natural sanctuaries has allowed for the preservation of fauna in the wilderness and zoological settings. On this matter, the politics of non-human architecture should focus on designing systems and spatial regulations that contribute to the lasting and proliferation of nature. Due to the latent danger, volcanic lands have often become a vessel for secluded nature, thriving in fantastical ways that only match the descriptions of indigenous mythology.

Crimson Hues on the Warpath

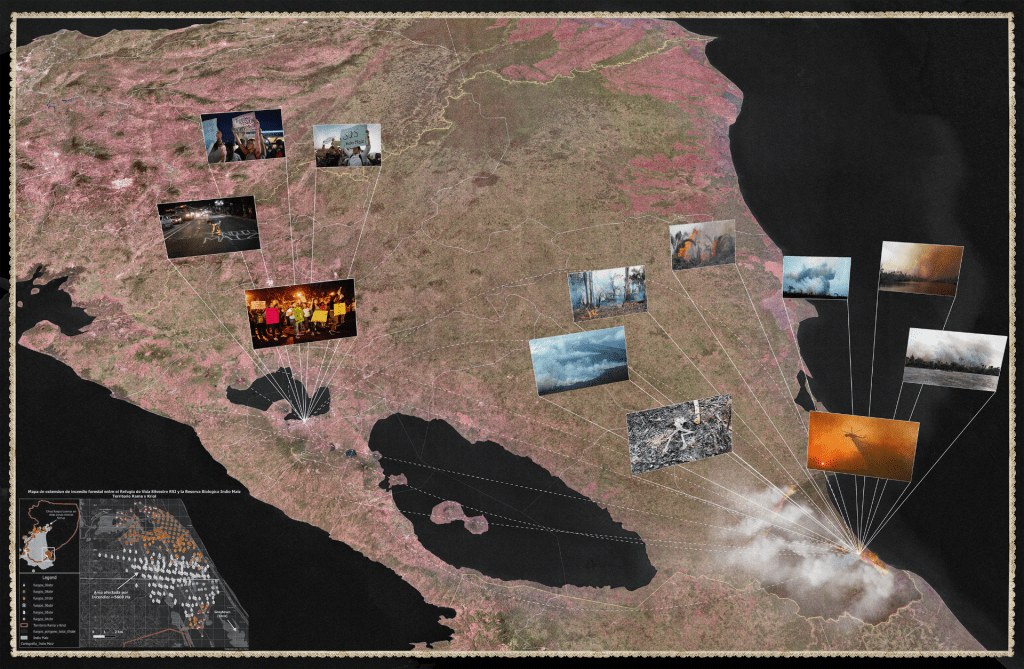

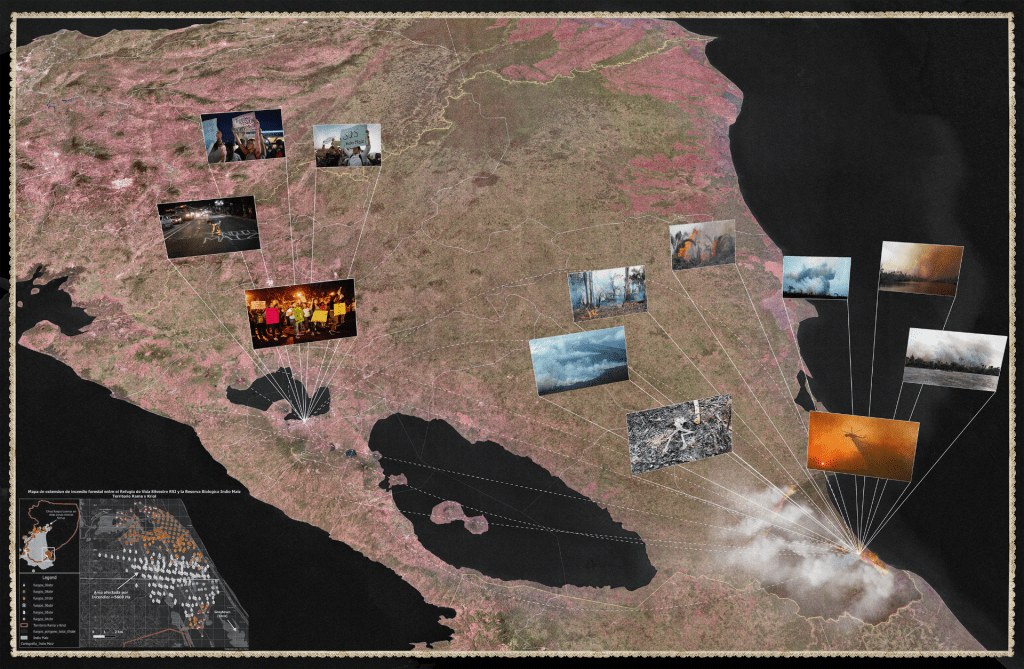

“Volcanic Fury”. Satellite diagram connecting Indio Maiz Biological Reserve burning with protests in Managua against the fire control mismanagement from the Nicaraguan government. Diagram by Oscar M Caballero.

The natural balance of paradisiac reservoirs in Nicaragua has been often maintained due to the volatility of the territory. Environments inhospitable to humans have flourished with endemic species of animals and plants along with uncontrolled governance of geographical formations.

In the southeast Caribbean of Nicaragua—relatively far from the volcanos on the Pacific coast—the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve rests under the camouflage of lush treetops and wetlands. It’s a region struck mostly by hurricanes, but in April 2018 it erupted with the force of a volcano when more than 12,000 acres burned, transforming its vivid greenery with a crimson gleam that unveiled a new dark monochrome landscape and greatly affected its wildlife.

The UNESCO-certified biosphere reserve, one of the most important humid tropical forests in the Central American region, hosts a variety of threatened or endangered species such as tapirs, jaguars, mountain pigs, manatees and a great variety of birds, such as limpets, toucans, quetzals and tiger herons. It’s also a sanctuary for neotropical migratory birds and bird species that have already disappeared from other regions of the country, such as peacock bass, limpets and the harpy eagle. These species have confronted the advance of agricultural gentrification, deforestation, the invasion of settlers from the interior of the country, the construction of religious temples and fires.

It is popularly known that the activity of a volcano could awaken another one and produce a chain reaction across the pacific range. Similarly, the volcanic fury at Indio Maíz lit a second political volcano after 40 years of perennial numbness and exploded with a third reaction, a city that resisted like a volcanic bastion. By the time the media transmitted the news on Indio Maíz, protests spread like wildfire, especially in the capital. The consequences of this forest fire reached the volatile Pacific coast to awaken a disobedient spark and propel the beginning of an insurgency against the unfair politics and mismanagement of the Ortega-Murillo government, including protests against pension reform.

Throughout the protests, one bird, in particular, became a symbol of rebellion because of its untamable nature: “El Guardabarranco” (Eumomota Superciliosa), the Nicaraguan national bird since 1971. The colorful bird is usually found near cliffs in forest regions and its singing serves as an advisory signal for unexpected topography. Even though this species of bird does not nest on tree branches and prefers to nest in secluded holes dug in the walls of cliffs or in caves, it cannot live in captivity. It is popularly known that the bird will charge against the cage incessantly seeking freedom until it meets its final rest. Vicariously, Nicaraguans opposing against the dictatorship projected the fervor for freedom through the symbolism of the bird. “El Guardabarranco,” in addition to being a national symbol, became an ideal of civic protest, an anthem for freedom and an inspiration for endurance.

Mountain of Fire, Valley of Water

“Volcanic entanglements”. Mapping of Masaya Volcano. Scanned charcoal/marker drawing with photomontage by Oscar M Caballero.

Upon the gravitational pull of two concave lagoons carved from past volcanic activity, there is a city made from movement traces. Its intricate streets reveal a pattern of constant displacement between geographical nodes, and the ruins of its colonial architecture are a monument to seismic endurance. Masaya, according to the late folklorist Eliseo Ramirez in his book Masaya indígena y mestiza, means “Land of Deers” or “Burning Mountain” in the náhuatl language. Today, deer can only be seen in protected environments to prevent extinction, but the burning mountain is more prominent than ever.

The Masaya Volcano—composed of Masaya, Nindirí, San Pedro, San Fernando, Comalito, Santiago and other parasitic cones—is one of the highest producers of lava in the Central American region since Pre-Columbian times. The National Park Volcán Masaya, owned by the Central Bank of Nicaragua, is intertwined with an architectural program that extends to the zoo, museum, magma port, trails and caves where multiple species of bats rest. The cauldrons are inhospitable due to the sulfur dioxide they emit constantly, but in an unusual manner, flocks of parakeets can be seen at sunset gliding through the volcanic gasses into the crater.

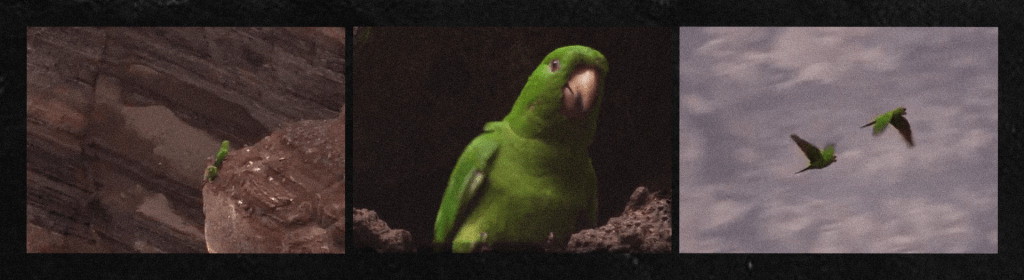

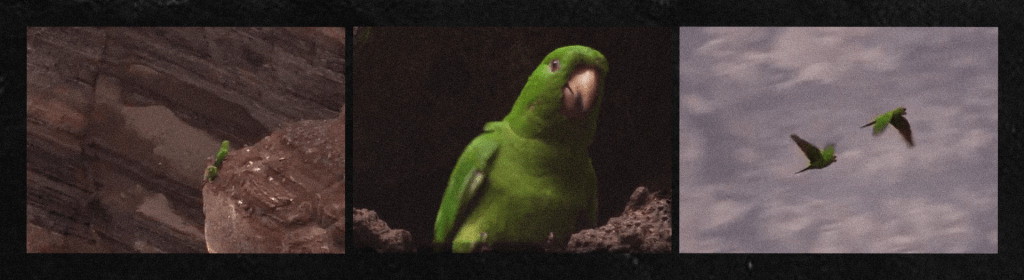

“Parakeets of Masaya Volcano”. Screenshots from NatGeo’s “Untamed Americas” documentary on Twitter.

In 2012, National Geographic released a documentary, “Untamed Americas.” A short segment in the first episode shows the unprecedented habitat of parakeets in the lands of the Masaya Volcano in Nicaragua. This species of bird has managed to live among toxic gasses emanating from the crater, where they have created a new ecosystem by nesting on holes they dug out of the soft soil. The reason why and how these parakeets are able to live among the toxic gasses remains unknown. Although, one could reason that their reclusive human-inhospitable shed might be a survival mechanism. The illegal trade of several species of parakeets and parrots is a deep-rooted practice in several parts of the country where cages full of these birds can be seen for sale along the roadside.

Parakeets are not the only species that have fled from human contact in the Masaya Volcano area. The seclusion of exotic fauna can also be found in indigenous tales. There are several variations of the origin legend of the Masaya lagoon, but the main storyline remains consistent: There was a valley surrounded by a lush forest and it was home of a fantastical beast, a horned snake as long as the contouring of the valley itself. Any attempt to kill the powerful animal guarding the valley would prove unsuccessful. Different tribes gathered and figured out a way to contain the snake. By losing its freedom, the snake deepened in sorrow and cried until its tears puddled on the ground. Eventually, tribes fled and the valley flooded. The horned snake lies at the bottom of the lagoon within the liquid realm it built to defer from human harm. A cautionary tale of a beautiful ojo de agua with an underwater guardian. This legend has been passed down for generations. Even though the valley and the snake are both a metaphor, they represent a sentiment. Allegorically, the narrative explores the volatility of the landscape and the connection between animals and human settlement. Not as opposing forces, but as elements of the same earthly cycle.

Let There Be Lava

Nicaraguan volcanoes will continue to influence territoriality across human and non-human forms of habitability. They represent the governance of nature upon other living affairs and it questions the human response towards climate manifestations. However, the Nicaraguan fauna has created an intrinsic connection with volcanoes, enduring the volatility of their eruptive nature by developing an endemic cohabitation. Joaquin Zavala Urtecho’s essay, “Los volcanes han sido para Nicaragua bendición y flagelo a la vez,” describes the volcanic range as a nervous system that binds the human psyche and geography with deep roots connected to the underground Pacific ring of fire wrapping across the world. In the words of Sabrina Duque, the volcano is a metaphor. It’s both animal and nature, geology and politics, home and foe.

DRAGONES EN EL HORIZONTE

Fauna endémica y formas de gobernanza volcánica

Por Oscar M Caballero

Sobrevolar la cordillera volcánica—compuesta por 19 volcanes alineados en la costa pacífica de Nicaragua—da la impresión de ver a criaturas de fuego en un sueño precario, despertando cada cierto tiempo con una sinfonía tectónica que agita la tierra como en forma líquida. El paisaje mesoamericano oscila entre mito y realidad. Las leyendas indígenas son de suma importancia para comprender la conexión humana con la naturaleza, la fauna, el clima y otras fuerzas terrestres, como los volcanes. El territorio nicaragüense ha convivido con tierras volcánicas en virtud de su capacidad de adaptación. En esta tierra de volcanes, los animales juegan un papel desmesurado, ya sea en las danzas tradicionales, en las reservas naturales o en el Volcán Masaya.

En el territorio mesoamericano precolombino, los animales tenían un rol cultural más allá de la agricultura y la ganadería. Los indígenas expresaban su aprecio por los animales con cualidades poderosas y divinas como jaguares, panteras, serpientes y fascinantes aves a través de elementos pictóricos, parafernalia y literatura mitológica. La fauna autóctona a menudo se pintaba, tallaba e incluso esculpía en medios de carácter arquitectónico, como senderos de piedra, paredes en cuevas y, más tarde, en edificicaciones. Estas prácticas desarrollaron una profunda conexión entre memoria y arquitectura que ha prevalecido hasta nuestros días. La presencia animal en el paisaje desencadenaría leyendas sobre lagunas y mitología volcánica, la denominación de regiones y creencias religiosas. Sin embargo, durante el período de la colonización, la cosmovisión europea consideraba a la cultura indígena como un folclore mítico pagano.

El mestizaje combinó los nuevos rituales católicos con las prácticas indígenas en una lenta amalgama de costumbres, a menudo presentando animales de una manera diferente. Por ejemplo, el drama satírico “El Güegüense o Macho Ratón”, proclamado por la UNESCO como obra maestra del Patrimonio Oral e Inmaterial de la Humanidad, gira en torno a encuentros entre autoridades españolas que portan máscaras con rasgos caucásicos e indígenas que portan máscaras de figuras ecuestres. Los bailarines indígenas maniobran formas ingeniosas para desafiar a la autoridad colonial. El uso de una máscara de caballo representa una abstracción metafórica de caballos salvajes que se oponen al cautiverio.

Un País Líquido

Los países con alta actividad volcánica como Nicaragua están en constante cambio. Los movimientos geológicos desencadenan procesos de colapso geográfico, político, urbano y arquitectónico. Este ciclo de renovación territorial mantiene un intrigante estado efímero en el paisaje. En su prólogo para VolcáNica: Crónicas de un país en erupción de Sabrina Duque, el escritor nicaragüense Sergio Ramírez describe a la nación como un territorio que aún no ha sido transformado geológicamente. Establece un paralelismo entre la geografía y la historia, en virtud de la actividad sísmica que sacude el reino subterráneo y las revoluciones políticas en la superficie que han provocado un tipo diferente de agitación, ambas con consecuencias atroces. Se podría percibir la geografía nicaragüense como en un estado líquido de permanencia temporal impulsada por su vulcanología para influir en la política, la planificación urbana y la evolución de la naturaleza. Esta liquidez territorial también lleva huellas de memoria, historias y formas de resilencia.

El paisaje posvolcánico ha demostrado ser una incubadora de fascinantes transformaciones naturales que redefinen los límites humanos y no humanos. Desde el surgimiento de nuevos ojos de agua a partir de cráteres volcánicos extintos, el nacimiento de islas sobre cuerpos de agua que originalmente formaban parte de material volcánico erupcionado, bosques inesperados de suelos fértiles posvolcánicos, transformación topográfica a escala de ciudad, asentamientos urbanos y desplazamientos a nivel nacional, y mutaciones de especies animales y vegetales.

Los rastros más antiguos de la presencia de animales que habitaban entre los nicaragüenses fueron impresos hace unos 6.000 años por una zarigüeya, un pájaro y un venado en lodo volcánico. Las huellas de Acahualinca fueron descubiertas por accidente en 1874 en la capital Managua cerca del lago Xolotlán. Durante décadas de estudios arqueológicos, se ha determinado que 18 personas divididas en dos grupos de hombres, mujeres y niños se alejaban a paso lento de una erupción volcánica. Entre los dos días de viaje, el grupo de animales pasó la noche siguiendo el mismo instinto en una trayectoria hacia el lago. La lava solidificaría estas antiguas huellas e influiría en el comienzo de un nuevo asentamiento humano que se centraría en la pesca y la agricultura. En tiempos modernos, el lago fue contaminado por décadas de gestión urbana precaria. Los expertos ambientales piensan que el mercurio ingerido en pescados como el guapote, las mojarras y las guabinas tendrá un efecto negativo a largo plazo en los consumidores.

La contaminación del lago Xolotlán no es un caso aislado. Múltiples cuerpos de agua en Nicaragua con características naturales únicas se han visto en peligro a través de modos de desperdicio que van desde el nivel institucional hasta el nivel local. Las especies animales y vegetales han sido las primeras en perecer o emigrar a lugares seguros. La protección de ciertas regiones como santuarios naturales ha permitido la preservación de la fauna en entornos salvajes y zoológicos. En este sentido, la política de la arquitectura no humana debe centrarse en diseñar sistemas y regulaciones espaciales que contribuyan a la perdurabilidad y proliferación de la naturaleza. Debido al peligro latente, las tierras volcánicas a menudo se han convertido en un recipiente para la naturaleza aislada, que prospera de formas tan fantásticas que asemejan a las descripciones de la mitología indígena.

Carmesí en pie de guerra

El equilibrio natural de las reservas naturales de Nicaragua se ha mantenido muchas veces debido a la volatilidad del territorio. Los entornos inhóspitos para los humanos han florecido con especies endémicas de animales y plantas junto con el anárquico nacimiento de formaciones geográficas.

En el sureste del Caribe de Nicaragua, relativamente lejos de los volcanes de la costa del Pacífico, la Reserva Biológica Indio Maíz descansa bajo el camuflaje de frondosas copas de árboles y humedales. Es una región azotada principalmente por huracanes, pero en abril de 2018 entró en erupción con la fuerza de un volcán cuando se quemaron más de 12,000 acres, transformando su vívido verdor con un brillo carmesí que desnudó un nuevo paisaje oscuro monocromático y afectó en gran medida su vida silvestre.

La reserva biológica certificada por la UNESCO, uno de los bosques tropicales húmedos más importantes de la región centroamericana, alberga una variedad de especies amenazadas o en peligro de extinción como tapires, jaguares, jabalíes, manatíes y una gran variedad de aves, como lapas, tucanes, quetzales y garzas tigre. También es un santuario para aves migratorias neotropicales y especies de aves ya desaparecidas de otras regiones del país, como el pavón, las lapas y el águila arpía. Estas especies han enfrentado el avance de la gentrificación agrícola, la deforestación, la invasión de colonos del interior del país, la construcción de templos religiosos e incendios forestales.

Es popularmente conocido que la actividad de un volcán puede despertar a otro y producir una reacción en cadena a lo largo de la cordillera del Pacífico. De igual forma, la furia volcánica de Indio Maíz encendió un segundo volcán político después de 40 años de perenne entumecimiento y estalló con una tercera reacción, una ciudad que resistió como un bastión volcánico. Para cuando los medios transmitieron la noticia de Indio Maíz, las protestas se extendieron como pólvora, especialmente en la capital. Las consecuencias de este incendio forestal llegaron a la volátil costa del Pacífico para despertar una chispa de desobediencia e impulsar el inicio de una insurgencia contra la política injusta y la mala gestión del gobierno Ortega-Murillo, incluyendo protestas contra la reforma de pensiones.

A lo largo de las protestas, un ave en particular se convirtió en un símbolo de rebelión por su naturaleza indomable: “El Guardabarranco” (Eumomota Superciliosa), el ave nacional de Nicaragua desde 1971. El colorido pájaro se encuentra generalmente cerca de los barrancos en las regiones boscosas y su canto sirve como señal de aviso para topografía inesperada. Aunque esta especie de ave no anida en las ramas de los árboles y prefiere anidar en agujeros cavados en las paredes de los acantilados o en cuevas, no puede vivir en cautiverio. Es de conocimiento popular que el ave embiste contra su jaula buscando incesantemente la libertad hasta encontrar su descanso final. Vicariamente, los nicaragüenses opositores a la dictadura proyectaron el fervor por la libertad a través del simbolismo del pájaro. “El Guardabarranco”, además de ser un símbolo nacional, se convirtió en un ideal de protesta cívica, un himno de libertad e inspiración para la resistencia.

Coloso de fuego, valle ahogado

Dentro de los trazos gravitacionales de dos lagunas cóncavas producto de actividad volcánica del pasado, hay una ciudad formada a partir de huellas de movimiento. Sus intrincadas calles revelan un patrón de desplazamiento constante entre nodos geográficos, y las ruinas de su arquitectura colonial son un monumento a la resistencia sísmica. Masaya, según el difunto folclorista Eliseo Ramírez en su libro Masaya indígena y mestiza, significa “Tierra de Venados” o “Montaña Ardiente” en lengua náhuatl. Hoy en día, los ciervos solo se pueden ver en entornos protegidos para evitar su extinción, pero la montaña en llamas es más prominente que nunca.

El Volcán Masaya—compuesto por cráter Masaya, Nindirí, San Pedro, San Fernando, Comalito, Santiago y otros conos parásitos—es uno de los mayores productores de lava en la región centroamericana desde la época precolombina. El Parque Nacional Volcán Masaya, propiedad del Banco Central de Nicaragua, se entrelaza con un programa arquitectónico que se extiende al zoológico, museo, mirador de magma, senderos y cuevas donde habitan múltiples especies de murciélagos. Los calderos son inhóspitos debido al dióxido de azufre que emiten constantemente, pero de manera inusual, se pueden ver bandadas de chocoyos al atardecer volando a través de los gases volcánicos hacia el interior del cráter.

En 2012, National Geographic lanzó un documental, “Untamed Americas“. Un breve segmento en el primer episodio muestra el hábitat sin precedentes de los chocoyos en las tierras del Volcán Masaya en Nicaragua. Esta especie de ave ha logrado vivir entre los gases tóxicos que emanan del cráter, donde han creado un nuevo ecosistema al anidar en agujeros que excavaron en el terreno blando. Se desconoce por qué y cómo estos chocoyos pueden vivir entre los gases tóxicos. Aunque, uno podría razonar que su refugio solitario e inhóspito para los humanos podría ser un mecanismo de supervivencia. El comercio ilegal de varias especies de chocoyos y loras es una práctica muy arraigada en varios puntos del país donde se pueden ver jaulas llenas de estos pájaros a la venta a lo largo de carreteras.

Los chocoyos no son las únicas especies que han huido del contacto humano en la zona del Volcán Masaya. La reclusión de la fauna exótica también se encuentra en los relatos indígenas. Hay variaciones de la leyenda del origen de la laguna de Masaya, pero la historia principal sigue siendo consistente: había un valle rodeado por un bosque frondoso y era el hogar de una bestia fantástica, una serpiente con cuernos tan larga como el contorno del valle mismo. Cualquier intento de matar al poderoso animal que custodiaba el valle resultaría infructuoso. Diferentes tribus se reunieron y descubrieron una forma de contener a la serpiente. Al perder su libertad, la serpiente profundizó en su dolor y lloró hasta que sus lágrimas se derramaron por el suelo. Eventualmente, las tribus huyeron y el valle se inundó. La serpiente yace en el fondo de la laguna dentro del reino líquido que construyó para evitar el daño humano. La historia de un hermoso ojo de agua con un guardián submarino. Esta leyenda se ha transmitido de generación en generación. Aunque el valle y la serpiente son ambos una metáfora, representan un sentimiento. Alegóricamente, la narrativa explora la volatilidad del paisaje y la conexión entre los animales y el asentamiento humano. No como fuerzas opuestas, sino como elementos de un mismo ciclo terrenal.

Lava será

Los volcanes de Nicaragua seguirán influyendo en la territorialidad a través de formas de habitabilidad humanas y no humanas. Representan el poderío de la naturaleza sobre otros seres vivos y cuestionan la respuesta humana hacia las manifestaciones climáticas. Sin embargo, la fauna nicaragüense ha creado una conexión intrínseca con los volcanes, resistiendo la volatilidad de su naturaleza eruptiva al desarrollar una convivencia endémica. El ensayo de Joaquín Zavala Urtecho, “Los volcanes han sido para Nicaragua bendición y flagelo a la vez”, describe la cordillera volcánica como un sistema nervioso que une la conciencia humana y la geografía con profundas raíces conectadas al anillo de fuego subterráneo del Pacífico que envuelve el mundo. En palabras de Sabrina Duque, el volcán es una metáfora. Es a la vez animal y naturaleza, geología y política, refugio y destrucción.

Oscar M Caballero is an architectural designer, researcher and visual artist originally from Masaya, Nicaragua. He holds a MAAD ’20 degree from Columbia University.

Oscar M Caballero es un arquitecto, investigador y artista visual originario de Masaya, Nicaragua. Tiene un Master en Diseño Arquitectónico Avanzado por Columbia University.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter – Animals

Editor's LetterANIMALS! From the rainforests of Brazil to the crowded streets of Mexico City, animals are integral to life in Latin America and the Caribbean. During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns, people throughout the region turned to pets for...

Where the Wild Things Aren’t Species Loss and Capitalisms in Latin America Since 1800

Five mass extinction events and several smaller crises have taken place throughout the 600 million years that complex life has existed on earth.

A Review of Memory Art in the Contemporary World: Confronting Violence in the Global South by Andreas Huyssen

I live in a country where the past is part of the present. Not only because films such as “Argentina 1985,” now nominated for an Oscar for best foreign film, recall the trial of the military juntas…