Education in Colombia

Partnering to Change

In a hotel bar in Medellín a year and a half ago, Governor of Antioquia Guillermo Gaviria, World Bank education specialist Martha Laverde, and Saúl Pineda, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) regional officer in Antioquia, shared cocktails and contemplated how to improve public education in Colombia. Since the Colombian educational system was decentralized about 20 years ago, local entities have identified problems and created their own solutions. Most of the Colombia’s 34 departments (the equivalent of U.S. states) have a secretary of education, each of whom deals day by day with short-term conflicts. Yet, as Gaviria pointed out to his companions, these officials were accumulating the knowledge and experience to help create a long-term plan for national educational reform.

Gaviria—dedicated to finding a political solution to 30 years of political armed conflict and a highly active leader in promoting peace talks in Antioquia—went on to affirm that education in should have two major purposes: First, it should provide children with the key to living harmoniously—an understanding and acceptance of cultural and political differences. And second, education should confer the abilities necessary to thrive in a modern society. With technology advancing everyday and communities faced with increasingly complex problems, children must learn to learn throughout their lives.

His companions agreed. What started as a casual conversation soon developed into a plan for a unique kind of partnership. Gaviria, Laverde and Saúl Pineda determined that transforming education should not be the exclusive responsibility of educators, but rather that members of the economic sector should also embrace this goal. They decided to organize a project in which the fiscal and education sectors would work hand in hand towards a long term plan for public education. Gaviria proposed that other governors be invited to participate and recommended that the World Bank and UNDP join as active members of a new partnership called “Equity of educational opportunities and regional competitiveness.” The three pioneers toasted to the future, confident that a local initiative could mobilize technical and financial resources and achieve radical, far-reaching changes.

PERSEVERANCE UNDER DURESS

After receiving my Master’s in education from the Harvard Graduate School of Education in 2001, I returned home to Colombia, where the project had taken off despite threats of violence from guerillas and paramilitaries. Martha Laverde invited me to work for the World Bank on the project. From 1998 to 2000 I had served as secretary of education for Cundinamarca, and was aware of the need for a long-term vision for education and cooperation with different sectors of society. I had witnessed that secretaries of education, who ostensibly directed policies, generally devoted too much time to “administrative” duties. I was thus happy to participate in a project that would encourage secretaries to conduct a cross-sector dialogue about how education was responding to social changes.

Some weeks after my appointment, the project was sketched out in a ten-page document and representatives from Antioquia met with their counterparts from two adjacent departments, Santander and Caldas, to discuss broad policy guidelines and define basic operations. However, in May 2002, Gaviria was kidnapped by the FARC (the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) while leading a peaceful demonstration against guerrilla and paramilitary activism in the region. In spite of voices raised throughout the country to demand his liberation, at this moment Gaviria remains a prisoner somewhere in the mountains of Colombia.

Laverde, the UNDP, the governors of Santander and Caldas, and the interim governor of Antioquia resumed their efforts with a renewed impetus. Carrying on with the project demonstrated that most Colombians willingly work for change in the face of violence. Indeed, the project itself was not only a bet to improve public education, but also an invitation to an open dialogue on peace in Colombia.

The World Bank was appointed technical secretary of the partnership. In February, 2002, the first meeting took place in Bogotá. By now, seven territorial entities—Antioquia, Caldas, Cundinamarca, Santander, Medellín, Cartagena, Pasto and Manizales—and two international organizations—the World Bank and the UNDP—had become active partners.

FORGING COMMON CONNECTIONS

As the partnership aims to achieve “equity of educational opportunities and regional competitiveness,” it challenges previously disconnected sectors to establish a constructive dialogue. All members contributed to two different versions of a technical document attempting to define the principles, goals and means of the partnership. As yet there is no final version. In fact, as the project moves on, new evidence appears about how difficult it is to come up with a common understanding of concepts such as equity, competitiveness, and development. These are not “neutral” notions, but used for different purposes by dissimilar agents and reveal distinct—even opposing—views about what society ought to be.

Rather than dancing around these challenging topics, the partnership has promoted a one-year agenda of panels and seminars aimed at feeding the debate. Last January, we invited the local director of the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean to discuss educational challenges in Latin America. Harvard Graduate School of Education professors Richard Murnane and Fernando Reimers will participate in a panel through videoconferencing this spring, and we expect French scholar Edgar Morin to visit us in the fall.

So far, members agree on the principle that sustainable development requires universal education of the highest quality so that people have the capability to learn, transform, create and improve their living conditions. We reject the idea of building competitive industries or competitive economies based on low salaries and poor working conditions. We disagree with the assumption that elite education for a few guarantees economic growth. Instead, we strongly believe that the provision of real and universal opportunities to learn and progress through the formal education system is the key to a just society and a strong economy.

However, the crucial issue we face is how to transform education in order to achieve equity and competitiveness in each one of the partnership’s distinct regions. The seven member territories share some features, namely the problems of poverty, violence and internal displacement, but differ significantly in others. By size they range from 400,000 to three million inhabitants. Pasto’s economy is based on agriculture, Antioquia’s on industry and Cartagena’s on culture and tourism. Hence, an enormous challenge for the partnership is to allow each territory to find its own condition-specific solutions while also contributing to a general policy for the country.

Each one of the seven territories has selected a local research institution to explore how education and the economic sector interact and how this relationship should promote equity and competitiveness. The researchers first determine their region’s educational and economic profile. They conduct interviews and focus groups with corporations, school administrations, teachers and students. Finally, researchers organize open forums to air different points of view about how education could contribute to equity and competitiveness and how other sectors—the economic sector in particular—might support educators in achieving such goals.

Four out of seven members have decided to adopt the project’s approach and data to create a ten-year educational plan. They will have to establish different strategies to involve as many people as possible in discussing the future of education and society in general. Even if this process does not radically change the course of education in Colombia, it nevertheless will contribute to a new way of thinking and, hopefully, a new practice. As an example of the potential of a long-term commitment of different social sectors to transform educational policies, the project sheds new light on how communities, states, nations and international organizations can work together to overcome diverse interests, establish common purposes, and ultimately achieve change.

No doubt, this will be a great learning experience for all involved. International partnership members must be prepared to learn rather than “prescribe” and reconsider their own development policies. Educators and education policy makers might learn to talk constructively with economists and planners. Economists and technocrats face the challenge of understanding public education beyond strikes and fiscal deficits. Personally, the greatest challenge I face is integrating the discourse about equity and competitiveness into an actual viable project. I know that such realizing this ideal might be a lifelong project for me.

María Carolina Nieto did her undergraduate studies in law and Master’s in politics at Essex University in the United Kingdom and received her M.Ed. at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. She lives in Bogotá with her husband and three-year-old child and enjoys poetry and the Colombian countryside.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.

Editor’s Letter: Colombia

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American…

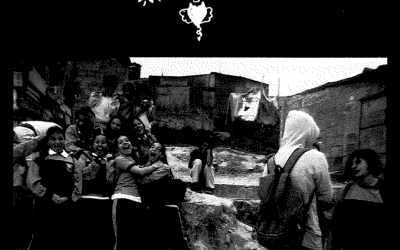

Photoessay: Shooting for Peace

Photoessay: Shooting for PeacePhotographs By The Children of The Shooting For Peace Project As this special issue of Revista highlights, Colombia’s degenerating predicament is a complex one, which needs to be looked at from new perspectives. Disparando Cámaras para la...