Evangelicals in Latin American Politics

In February 2006, while doing field research in Peru for the doctoral dissertation that would become Presidential Campaigns in Latin America, I attended a rally for Humberto Lay, a neo-Pentecostal pastor and candidate for president. Given Lay’s single-digit poll standings, I expected the rally to be a small affair and that I could easily corner one of his advisors to introduce myself.

When I arrived in Lima’s downtown Campo de Marte park, I saw that thousands of Lay’s supporters had filled the park that warm summer night, swaying to the music of Christian rock artists on a massive stage. I had severely underestimated the draw of the somewhat quiet and reserved evangelical politician. Lay’s attendance was noticeably better than that of Alan García, the eventual election winner, at another rally I attended later in the same park. I learned a clear lesson that night: do not underestimate evangelical politicians in Latin America.

Latin America’s religious landscape has been transformed over the past several decades by the growth of evangelical Christianity. In a region where religion was once synonymous with the Catholic Church, more than a fifth of all Latin Americans now identify with non-Catholic Christian denominations. In most Central American countries, figures have reached as high as 40% in recent surveys, approaching the share who describe themselves as Catholic. In everyday Spanish and Portuguese, evangélico is effectively a synonym for Protestant, encompassing born-again Christians but also mainline denominations that would not normally be considered evangelical in an English-language sense. Yet while Anglicans, Methodists and Lutherans have a long presence in the region, their numbers have always been small. Today, around two-thirds of Latin America’s Protestants identify with Pentecostal or charismatic Christianity, movements that emphasize gifts of the Holy Spirit such as speaking in tongues and faith healing.

Solomon’s Temple, headquarters of Brazil’s Universal Church of the Kingdom of God Local: São Paulo/SP. Data: 07/07/2017. Foto: Alexandre Carvalho/A2img

Evangelicals’ growing numbers have translated into formidable political influence in parts of the region. The evangelical caucus in Brazil’s Congress has been growing steadily in size since the mid-1980s. More than one out of every five congressional representatives identifies as evangelical. In the 2018 presidential election, evangelicals were a crucial support base for Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right populist who describes himself as Catholic but is close to evangelicals (and is married to one). In Costa Rica, evangelical pastor and gospel singer Fabricio Alvarado topped the polls in the first round of the 2018 presidential election. Though defeated in the runoff, his National Restoration Party gained a quarter of the seats in Congress, giving Costa Rica the region’s largest evangelical caucus in percentage terms. Elsewhere, evangelical parties and politicians have made headlines for their support for Andrés Manuel López Obrador in Mexico and their mobilization against Colombia’s 2016 referendum on a peace accord with the FARC.

Thirteen years after my visit to Humberto Lay’s rally, I met up with Christian Rosas, spokesman for Peru’s conservative social movement ConMisHijosNoTeMetas (Don’t Mess with my Children), in January 2019. The son of congressman and neo-Pentecostal pastor Julio Rosas, Christian attended Liberty University in Virginia, the evangelical college founded by Jerry Falwell. As he ushered me into his Lima office, Rosas explained with a laugh that he had once been one of about three members of Liberty’s Young Democrats club. Whatever his “youthful indiscretions,” Rosas has long since come back to the fold of social conservatism. He and his movement, which has been spreading around the region, have led grassroots opposition to progressive policies on gender and sexuality in Peru. Between the father’s maneuverings in Congress and the son’s organizing street marches and protests, the Rosas family takes credit for bringing down two Ministers of Education who had sought to integrate modern perspectives on gender and sexuality into Peru’s national public school curriculum.

Protesters from the social conservative movement “ConMisHijosNoTeMetas” in the 2018 March for Life in Lima, Peru. 05/18/2018 Photo by Mayimbú

Julio and Christian Rosas represent the most visible face of evangelical political mobilization in Latin America—a socially conservative reaction to recent progressive trends on abortion, same-sex partnerships, and related issues. Yet Latin America’s evangelicals are diverse. Not all politicians from this community are committed culture warriors. In January 2015, I interviewed a very different type of evangelical politician: Edmundo Salas de la Fuente, a Pentecostal Christian and longtime deputy from Chile’s Christian Democratic Party, which has been aligned with the Left since the transition to democracy. Like many in his party, Salas was more conservative on cultural issues than on the economy or human rights, the main policy areas that united the center-left Concertación. Yet his motivating cause was a different one. In 1992, he had been one of the sponsors of a bill to ensure legal equality between religious minorities and the Catholic Church, a later version of which became law in 1999.

While culture war issues have motivated much of evangelicals’ recent involvement in Latin American politics, the struggle for legal equality with the Catholic Church was what originally drew many of them into the political arena. In the lead-up to Brazil’s 1986 constituent assembly election, a number of evangelical denominations mobilized to elect their own representatives out of a fear that the Catholic Church was maneuvering to expand its own legal privileges, including its potential reestablishment as a state-sanctioned religion, a status it had not enjoyed since 1890. The evangelical powerhouse Assemblies of God went so far as to endorse an official slate of church-member candidates, some of them chosen through state-level primary elections. For Pentecostal denominations such this one, electoral mobilization was a marked departure from a long history of rejecting worldly affairs. For decades, the prevailing attitude among Brazilian Pentecostals was “believers don’t mess with politics.” Starting in 1986, this motto was swapped out for another: “brother votes for brother.”

The leadership of Brazil’s Assemblies of God made a collective decision to enter electoral politics in 1986, but many Pentecostal incursions into Latin American politics have been driven by individual charismatic clergy. In January 2015, I visited the church of Salvador Pino Bustos, a independent neo-Pentecostal pastor in Chile who launched an ill-fated bid for president in 1999. Pino had agreed to an interview before his Saturday evening worship service, so I arrived early, but the pastor was running late. Contemporary Christian music had already started by the time he stepped through the door and was thronged by congregants. Brushing them aside, he led me to his office, where he reminisced for half an hour about his political adventures. After several knocks on the door—“Bishop, it’s time!”—he acknowledged that he needed to get back to his flock. Returning to the sanctuary, he strode up to the stage as the worship music rose to a crescendo and then launched into his sermon before a rapt audience.

Salvador Pino’s political career may have met with little success, but other neo-Pentecostal clergy have used their charismatic leadership to build veritable political empires. Edir Macedo, founder of Brazil’s Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, has been the most prominent and arguably the most successful. Though Macedo himself has never run for office, his church is one of the best-represented in Brazil’s Congress, and his nephew Marcelo Crivella has served as senator and mayor of Rio de Janeiro. Once jailed in the early 1990s on charges of fraud and quackery, Macedo has become a political power broker, eagerly sought out by politicians across the ideological spectrum. His strategic alliance with Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2002 is seen by many as a key component of the Workers’ Party’s successful shift to the center in that election.

The growth and political influence of neo-Pentecostal denominations like Brazil’s Universal Church has been aided by their embrace of prosperity theology, the doctrine that material wealth is a sign of God’s blessing and that donations to the church are an investment that will yield future financial returns. This “health and wealth” gospel has helped make neo-Pentecostalism extremely popular among lower- and middle-class populations, and it has made churches—and their leaders—extremely rich. The Universal Church’s headquarters in São Paulo is a massive replica of Solomon’s Temple that seats 10,000. In addition to political influence and large buildings, the church’s wealth has bought a formidable media presence. Edir Macedo and his wife are sole owners of the Record Group, one of Brazil’s largest media conglomerates, whose holdings include the country’s second largest broadcast television network.

Yet despite the wealth and outsize political influence of figures such as Macedo, many evangelical politicians in Latin America are of more humble origins. In January 2015, I interviewed Héctor and Francesca Muñoz in their modest home in Concepción, Chile. Sitting down to share onces at their kitchen table, Héctor and Francesca told me how they got their start in politics as evangelical student activists at the University of Concepción, where Héctor was elected president of the student federation, traditionally dominated by the Left. After college, they started running for public office, with the Eagles of Jesus student ministry that they had founded providing grassroots support for their campaigns. Though the Muñozes eventually joined the mainstream right-wing party National Renewal—and Francesca would later be elected to Congress on its list in 2017—both believed that evangelicals lack a natural home in Chilean politics, given their conservative stances on sexuality politics but more lower-class social origins and frequent support for progressive socioeconomic policies.

Both faces of Latin American evangelicalism—“health and wealth” prosperity theology and the grassroots mobilization of believers of humble origins—were visible during Chile’s 2017 general election campaign. Evangelicals made headlines when Eduardo Durán Salinas, a candidate for Congress, gave a fiery speech attacking the Bachelet government’s policies on abortion and same-sex unions at an ecumenical worship service where the president was in attendance. Durán’s father, head bishop of the lavish Santiago cathedral of the Methodist Pentecostal Church, was later investigated by Chile’s tax agency for laundering money that the church received as tithes, and Durán himself—now an elected deputy—was fined by the Congressional Ethics Committee for failing to declare that he was receiving a share of these funds.

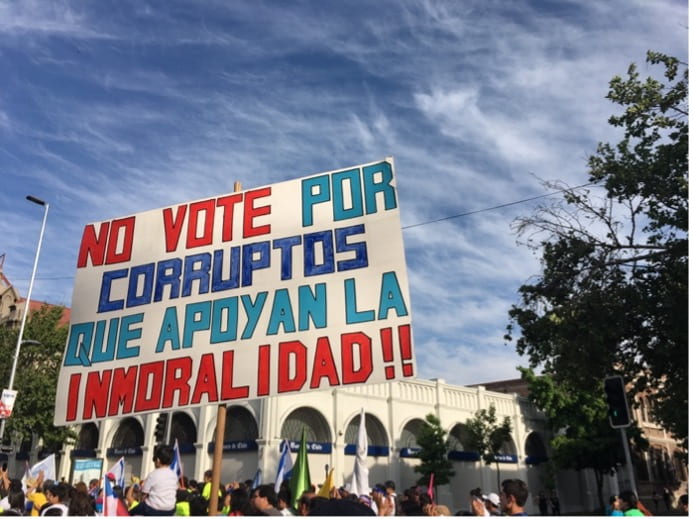

Such ostentatious displays of ill-gotten wealth were absent from another prominent evangelical event that I attended during Chile’s 2017 election campaign. On a national holiday in late October that commemorates the start of the Protestant Reformation, the March for Jesus in downtown Santiago brought thousands of evangelicals—including a notable number of Haitian immigrants—out into the streets, processing toward the presidential palace for a rally. Campaign volunteers handed out advertising for evangelical congressional candidates, and signs implored Chileans to vote against corrupt and immoral politicians.

Chile’s evangelical candidates experienced limited success in the 2017 election, but the political mobilization of Latin America’s growing evangelical community is only likely to gain force in the future. Chilean evangelicals were spurred to action in 2017 by a wave of progressive legislation on sexuality politics, including the legalization of same-sex civil unions and liberalization of abortion laws. In Costa Rica’s 2018 presidential election, Fabricio Alvarado surged in the polls after a decision by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in favor of same-sex marriage helped polarize the race around this issue. As Amy Erica Smith and I argue in a new working paper, progressive policy changes and social movement activism on gender and sexuality raise the salience of these issues, leading both religious identity and issue attitudes to influence people’s choices at the polls. Progressive candidates are likely to benefit from this dynamic, but so are socially conservative opponents. Argentina’s legalization of abortion in December 2020 is only the most recent example of a trend that is likely to spur more evangelical candidacies, and electoral victories, in the future.

Winter 2021, Volume XX, Number 2

Taylor C. Boas is Associate Professor of Political Science and Latin American Studies at Boston University and was Custer Visiting Scholar at DRCLAS in 2017–18. His current book project is entitled Evangelicals and Electoral Politics in Latin America: A Kingdom of This World.

Related Articles

Indigenous Peoples, Active Agents

Recently, the Amazon and its indigenous residents have become hot issues, metaphorically as well as climatically. News stories around the world have documented raging and relatively…

Beyond the Sociology Books

If you are not from Colombia and hoping to understand the South American nation of 50 million souls, you might tend to focus on “Colombia the terrible”—narcotics and decades of socio-political violence…

Exodus Testimonios

The audience at Iglesia Monte de Sion was ecstatic as believers lined up to share their testimonials. “God delivered us from Egypt and brought us to the Promised Land,” said José as he shared his testimonio with the small Latinx Pentecostal church in central California…