Exploring Mexican Judaism

A Personal Story

I was shivering on that sunny warm Mexico City afternoon in March 2019. The climate-controlled archives of the newly inaugurated Centro de Documentación e Investigación de la Comunidad Ashkenazi de México (CDIJUM) were otherwise a delight. Designed to incorporate Mexico City’s Rodfe Sedek synagogue, founded in 1931 by immigrants of Aleppo Syria, the modern documentation center of Mexican Jewry was purposefully envisioned to indicate an alliance between all Jewish communities of the country, including those of Ashkenazi, Sephardic, Syrian (both Aleppo and Damascus) and U.S. descent. Over the past century, each of these strands of Mexican Jewry, had founded independent religious, cultural and educational institutions. A couple of exceptions did exist: the Centro Deportivo Israelita (CDI), a community sports center founded in 1950, and the bridge organization between the Jewish communities and the nation, el Comité Central de la Comunidad Judía de México (CCCJM), established in 1938.

The CDIJUM was designed and constructed by architects Ezra Cherem y Alan Cherem, including the restoration of the Rodfe Sedek synagogue and mikvah. Photo by © LGM Studio – Luis Gallardo.

The director of CDIJUM, Enrique Chmelnik, happens to be a close childhood friend of mine. Two months after the center opened, my extended family and I were honored to receive a personal tour of the museum’s prized holdings. We got to gaze at a chumash (five books of the Torah) in Hebrew and Ladino, samples of family seder plates and menorahs, and archives containing illustrations by Diego Rivera (who claimed Portuguese Jewish descent and was a known friend of the Mexican Jewish community). We browsed samples of family repositories that we learned included more than 8,000 photographs. There was much more than we could take in on one visit: recovered Jewish texts from Nazi Germany and anti-fascist Mexican propaganda posters printed by a society of artist/activists, among whom were counted two Mexican-American women that I was incidentally researching at the time. The CDIJUM also houses materials on Jewish communities beyond Mexico City, such as Monterrey, as well as small communities of Mexicans who identify as descendants of crypto Jews, such as Venta Prieta in the state of Hidalgo.

As my now Mexican-American family sat among the first few rows of seats set up in the gorgeous Syrian Jewish synagogue founded almost ninety years prior, the rounded beams and colorful artwork now included a library and study hall for the new documentation and archive center. I took pictures with my own children and cousin’s children on the synagogue’s bimah (podium) and in front of the ark (which had held the holy scrolls), before walking downstairs to one of the country’s first mikvahs (ritual baths), and then entering the meticulously categorized archives. The next night, my Ashkenazi cousin was getting married to a woman of the Syrian community in the capital’s modern Sephardi synagogue (considered by many to be the most beautiful in Mexico City), located in the suburbs where most Jews have moved. The new generation, like the CDIJUM, represents a new openness to integration between the Jewish communities of Mexico.

Jewish communal life in Mexico did not begin in earnest until after the 1910 revolution; and especially after 1917, when the new anticlerical constitution was ratified. Yet already in 1912, Jews of all ethnic backgrounds gathered together under the auspices of the Monte Sinaí community which by 1918 had founded a synagogue, school and a cemetery. In 1922, the Ashkenazi Jews separated from the Monte Sinaí alliance due liturgical and cultural differences. This led to the founding of distinct communities where those of similar ethnic, linguistic, liturgical and cultural backgrounds banded together to form their own synagogues, schools, mikvahs and youth movements. Thus, Jewish Mexico became a community of communities, delineated by the Ashkenazi, Sephardi, and Syrian (with distinctions between Jews hailing from Aleppo (Hallebi) or Damascus (Shami)) sectors. Among the early Jews of Mexico were also U.S. Jews who first moved to Mexico to escape the draft for World War I, forming the Young Men’s Hebrew Association, and later included an expat business community centered at the Beth Israel congregation. There were also those relatively few but culturally significant U.S. Jews who were among the foreign artists and writers who took refuge and inspiration in post-revolutionary Mexico.

Current Jewish population estimates in Mexico come in between forty and fifty thousand, making it the fourteenth largest in the world, with over 95 percent living in the capital city, and the rest centered in Monterrey, Guadalajara, Tijuana, Cancun and Veracruz. Today’s Mexican Jewish community supports 16 Jewish day schools, and 90 percent of Jewish families send their children to these schools. All but two synagogues in Mexico City follow Orthodox tradition, even if many of its members are largely secular in their day-to-day observance, particularly among Ashkenazis.

Almost two decades before my visit to CDIJUM, I came to Mexico City as a graduate student at Stanford University to investigate how the Ashkenazi Jewish community of Mexico told its own story. At the time of this latest visit in March 2019, I was researching Mexican-American women’s involvement in the Mexican Renaissance, a cultural movement coined as such by Anita Brenner, who was incidentally a student of Franz Boas, a German-Jewish immigrant and founder of the Anthropology Department at Columbia University. The Mexican Renaissance brought members of the nation’s bohemian circles together. Many were commissioned by the country’s centralized education and anthropology sectors in the aftermath of the revolution to enunciate a new Mexican narrative, or perhaps more accurately, to produce a narrative of the new Mexican. At times, these culture makers and activists were also members of Mexico’s Communist Party, as well as artists whose work was commissioned internationally. Some, such as David Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco and Diego Rivera, formed part of the Latino and Caribbean art movement in New York that thrived between 1900 and 1942 (Cullen, Nexus New York: Latin American Artists in the Modern Metropolis).

I found it fitting to see sketches by Rivera in the archives of the CDIJUM, documenting as such that Jews were a part of the Mexican national story and of its storytelling. Enrique placed archivist gloves on his hands as he handled these alongside Jewish immigrant memoirs and photographs, and anti-fascist propaganda posters of the 1940’s published by the Taller de Gráfica Popular. It was in this context that Enrique showed us a copy of a 1936 book on Mexican history; authored in Yiddish by newspaperman Isaac Berliner and illustrated by Diego Rivera, it was intended to educate Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants to Mexico about the history of their new home precisely when Mexico was telling its own history anew. (Shtot Fun Palatsn/A City of Palaces was translated into English only in 1996 for the consumption of U.S. Jews with the patronage of Isaac Berliner’s son, Dr. David Berliner. To my knowledge it was never translated into Spanish.) According to Berliner’s granddaughter, Diego and Isaac met at Communist Party gatherings, and they would at times be joined on Sunday walks by Diego’s wife Frida Kahlo (see Rachelle Grossman’s article on “Mexican Yiddish and Secular Identity” in this issue).

As we were admiring the illustrations alongside the Yiddish text, my uncle Abraham informed Enrique of his great uncle Tio Salomon Hale’s friendship with Diego Rivera. It turns out Diego even painted a portrait of Tio Salomon, which can be seen in family photographs. My mother’s great uncle was known for his impressive collection of artwork, one of which was a wedding gift that hung in our dining room in San Diego my entire childhood.

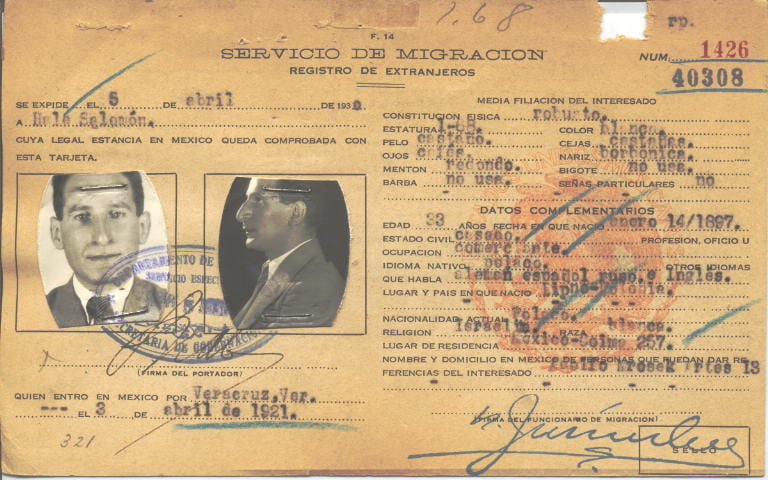

Salomon Hale’s immigration record from Poland to Mexico, via Cuba. Credit: Archivo General de la Nación.

I was born in San Diego, California, in 1978, less than a year after my parents immigrated from Mexico City. Throughout my early years, my parents’ nostalgia for Mexico and particularly, for the Mexican Jewish community, was palpable and explicit. Finally, as I was to begin junior high school at the age of twelve, we “moved back.” My father would say, “se me va a cocer el arroz.” It was imperative that we children live there during our formative years; otherwise, the Mexican Jewish identity that defined them would not be salient in the same way for me and my siblings. I understood the significance of the move, and made the most of it: I joined the local Israeli dance movement (my group won second place one year in the Festival Aviv, an international festival hosting groups from across the Americas and also Israel). I also became the assistant director of our school’s Jewish theatre Habima group, named after the one in Tel Aviv. My world was Mexican Jewish: I joined the Sofim (or Mexican scouts, named as well for the Israeli iteration) and went to the Colegio Israelita de Mexico. I recall that the curriculum focused as much on Hebrew and Tanach (bible) as on Yiddish literature and geshichte (Ashkenazi Jewish history, taught in Yiddish by the lereke (teacher) Jane Befeler, an institution unto herself).

I have always loved history, and recall the pride I took in interviewing my grandfather in his native Yiddish on his coming to Mexico at age seven from Skvira, Russia. These sessions sometimes followed marathon gin-rummy tournaments between me and my twin brother and my grandparents. My grandfather would always seal the competition with treats from his prized candy stash; my grandmother is a health-nut and I think that we were often the excuse for him to be allowed to have sweets as well!

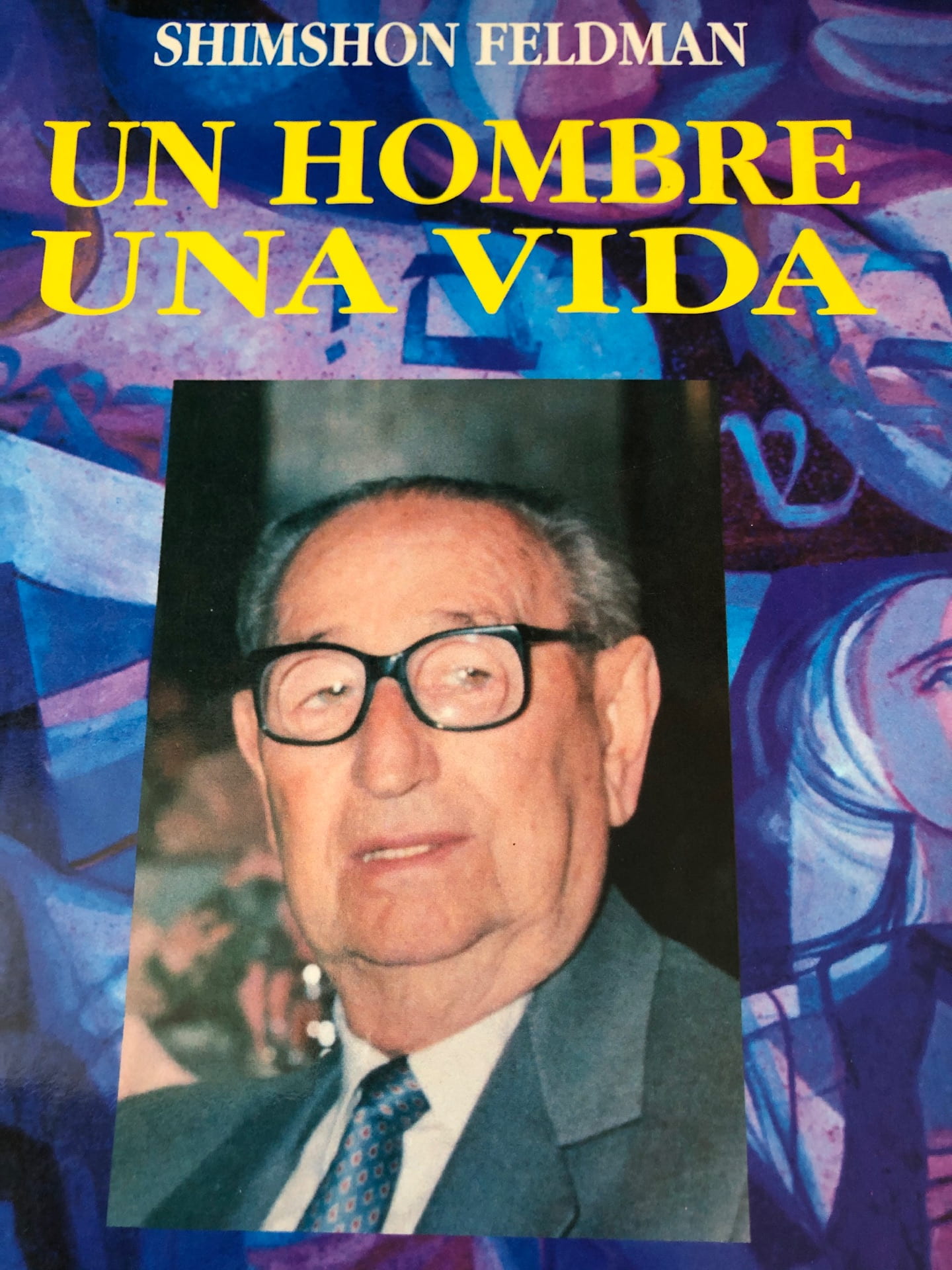

My family was part of the institutional life of Mexico. The Ashkenazi Jewish community was led for four decades by my great-uncle on my father’s side, Shimshon Feldman. I grew up hearing stories of his local leadership as well as visits with Golda Meir (and his recollections of her wit: for example, when my great uncle inquired once about the prudence of opening a certain business in Israel, she allegedly replied: “does it matter if one Jew doesn’t make a living, if another hundred do?”). Shimshon was celebrated as a founding leader of the Ashkenazi Mexican community, and I have a copy of his authored book containing his recollections. He is mentioned in any rendition of Mexican Jewish communal leadership (Shimshon Feldman: Un hombre, una vida; Generaciones Judías en México (1922-1992); Ashkenazi Jews in Mexico: Ideologies of the Structuring of a Community; Huellas: Judíos Ashkenazitas destacados de México).

In my immediate family’s move back to Mexico in 1990, I came to understand the depth and diversity of the Mexican Jewish experience, as well as to appreciate my own family’s place within this story. We were Ashkenazi Jews who, not that long ago, made their homes in Mexico and joined with other immigrants to help Mexico become that home for over 40,000 other diaspora Jews. My own family’s move to California in the 1970’s was an early indicator of another trend, one that would result in one out of every three Latin American Jews migrating away from their Latin American homes in generations to come, mostly to the United States or Israel.

A beacon for local and foreign visitors alike, Monica Unikel-Fasja has dedicated her professional life to illustrating the history of Mexican Jewry and its salience for today’s evolving community. She leads trips to the old downtown la Merced neighborhood for contemporary Jewish day school students, community members,professional associations and foreign tourists, all who embark on Monica’s famous tours to Jewish Mexico to learn about their own pasts and the diversity of the Jewish diaspora experience. Unikel has been leading these tours for more than 25 years, and she is also responsible for restoring the Justo Sierra Synagogue. Founded in 1922 as Mexico’s second synagogue, the Nidje Israel community, it now functions as a cultural center.

Of note, the synagogue on Justo Sierra street (in Mexico, synagogues are called by the streets on which they are located), was designed as a direct copy of the synagogue in Shavel, Lithuania. Recently the granddaughter of a Lithuanian Nazi war criminal from Shavel, addressed this very Mexican community as part of her efforts to address her own family’s legacy by ousting her grandfather not as a Lithuanian war hero but as a villain of the war. Yet, Mexico’s Jewish community was founded primarily through immigrants in the interwar period, in part due to Mexico’s own resistance to serve as a refuge for European Jews during the second world war (see Daniela Gleizer’s Unwelcome Exiles: Mexico and the Jewish Refugees from Nazism, 1933-1945).

Justo Sierra synagogue was where my two sets of grandparents were married, and Tio Abraham was bar mitzvahed before the community moved to the Acapulco 70 locale (for more on Mexico City synagogues, see June Carolyn Erlick’s NYTimes article). My paternal grandmother tells the story that for her wedding day, her own mother gave her a choice of a present: a wedding dress or a stove. She chose the dress, a choice she told me reflected her perspective that one day she would have a stove, but she would never have another opportunity for a wedding dress. At sixteen, she knew herself well; fashion was always more her strong suit than cooking.

A visit today to Justo Sierra, as to CDIJUM, provides contemporary testament that Mexican Jewry was formed by immigration from all over the Jewish diaspora, and that the communal life and institutions that were created in the inter-war period produced in Mexico a community of communities. Yet in my latest trip, I appreciated through my visits to re-imagined institutions, as at my cousin’s wedding, that the next generation of Mexican Jews are more interconnected now than ever before. Moreover, as we dined with Enrique’s family the evening of the joyous spring festival of Purim, after attending synagogue in Polanco where my children read the Hebrew text alongside the Spanish and made noise with groggers that read “Viva México,” I understood that Mexican Jewry has been changed in more modern times as much by in-migration from other Latin American countries, namely Venezuela and Argentina, as well as by those families whose members have ventured beyond Mexico to the United States or Israel, depending on their ambitions, possibilities, family ties or ideals. Mexican Jewry is part of the Latin American Jewish diaspora and as such, evidences a transnational element, one that is reflected in Enrique’s Argentine wife and in families like mine who are divided across the border, but maintain strong family and communal ties.

Though the Jewish community that was founded a century ago in Mexico remains a community of communities, an archive and historic cultural center now join the sports center and central committee to tell a more inclusive story of its foundation, as well as an evolving one. What it means to be a Mexican Jew has become much more expansive in its past and future implications. Writing today from Boston Massachusetts, I am a part of that story.

Winter 2021, Volume XX, Number 2

Dalia Wassner, Ph.D. is the director of the HBI Project on Latin American Jewish & Gender Studies (LAJGS) at Brandeis University. She is a historian whose work provides more inclusive and interdisciplinary approaches to the Jewish Diaspora. To learn more visit LAJGS, or listen to Episode 6 of the Jewtina y Co podcast.

Related Articles

Indigenous Peoples, Active Agents

Recently, the Amazon and its indigenous residents have become hot issues, metaphorically as well as climatically. News stories around the world have documented raging and relatively…

Beyond the Sociology Books

If you are not from Colombia and hoping to understand the South American nation of 50 million souls, you might tend to focus on “Colombia the terrible”—narcotics and decades of socio-political violence…

Exodus Testimonios

The audience at Iglesia Monte de Sion was ecstatic as believers lined up to share their testimonials. “God delivered us from Egypt and brought us to the Promised Land,” said José as he shared his testimonio with the small Latinx Pentecostal church in central California…