First Take: Guatemala, Guatebuena, Guatemaya

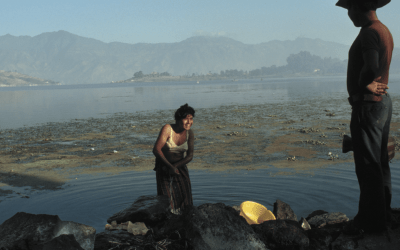

“Guatemala is more of a landscape than a nation,” a friend observed in 1996 when I returned to the country after thirty years of on-and-off absence. I knew as much as anyone could know about events in the country in the pre-Internet era: massacres, democracy, military groups, guerrillas, elections, and yet that particular remark lingered in my mind. Just before my plane landed in La Aurora Airport in Guatemala City, I glanced down at a tourist pamphlet and a novel by Miguel Angel Asturias I was holding. The pamphlet showed a beautiful reality transformed into commerce to attract foreigners, while the book evoked a fantasy built by Asturias’ words to reach another reality, the indigenous world. In the tourist pamphlet, Lake Atitlán looks glued by its green water to its three volcanos, Tolimán, Atitlán and San Pedro, all features that make it one of the most beautiful places in the world. And not far from Panajachel, in San Martín Chile Verde, on this very same lake, the novel describes the life of Celestino Yumi, a Quiché Indian who sold his wife to the Tazol devil, only to get caught up in the clutches of “that mulata woman.” Mulata de tal is perhaps our Miguel Angel’s finest novel. Then, shortly after my arrival, I learned that on these verdant shores of the lake and in San Martín, there had been many, many deaths, those of local peasants, guerrillas and soldiers.

“THE GUERRILLA MOVEMENT THAT DOES NOT LOSE, WINS”

That particular year of 1996 was a special one; “the internal armed conflict,” as officious history would keep calling it, was coming to an end. Some cite 1954 as the year it all started, when President Jacobo Arbenz was forced out of government through the betrayal of his fellow colonels and U.S. pressure; for others, the period of strife began in 1964, when Cuban influence stimulated the rise of the guerrilla movement, and hundreds of young people with more convictions than arms took to the mountains. I experienced this period myself, and I would place its beginning with the fratricidal urban riots in March and April 1962. The military police and the army killed more than fifty demonstrators in the streets of Guatemala City. Lieutenant Marco Antonio Yon Sosa made his appearance during this upheaval, and one has to remember that the first guerrillas were military men, young rangers who organized the Revolutionary Movement November 13 following an unsuccessful uprising against President Miguel Ydígoras.

Thus, in 1996, I waited with several friends in the Plaza of the Constitution. The ceremony for the signing of the Firm and Lasting Peace Accord was taking place in the National Palace, and we watched generals, politicians, guerrilla leaders, and a select public as they arrived. December 29, 1996, was a chilly night. We didn’t mind the cold: 34 years and two generations of Guatemalans wounded by terror were being left behind. The terror cannot even be conveyed by the statistics, some 150,000 dead. The startling figure makes me think of Stalin’s criminally cynical remark that the murder of one person is a crime, but the murder of many is just a statistic.

It is painful but certain that when one counts death in the hundreds of thousands, precision no longer matters. Perhaps percentages tell us more: 92% of the victims were non-combatant civilians; 54% were younger than 25 years old, and 12 % were women raped or physically attacked in various humiliating ways.

I believe that there was no civil war in Guatemala, and I’ve allowed myself to express this dissenting view both in writing and in oral debate. What happened here was a permanent repression by the state, punishing everyone who was considered as part of the political opposition in thought or deeds. This imbued military action with the logic of war-—a military campaign to destroy “subversive” opposition—and what resulted was the systematic destruction of hundreds of union leaders, peasants and students. This went on for three decades.

During this historic time, there were two moments of guerrilla insurgence. The first occurred between 1965 and 1968 and ended quickly in the middle of great confusion. This movement followed the foco theory developed by Che Guevara, calling for vanguard actions of guerrilla cadres leading to general insurrection. The other movement, ten years later (1980-83), advocated the strategy of “the prolonged popular war” in the style of Vietnam. The 1981 guerrilla offensive was smashed by the better organized and more heavily armed Guatemalan army.

The Guatemalan National Revolutionary Union (URNG) suffered a military defeat from which it never recovered, I believe. The military life of the guerrilla insurgency was quite brief, but its political life was long. Its polemical presence allowed it to survive until 1996, negotiate with three successive governments, and sign a substantive and wide-ranging peace agreement. How can one evaluate what happened between 1962 and 1996? It is fitting to remember U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s comment in the January 1969 issue of Foreign Affairs: “The guerrilla wins if he does not lose; the conventional army loses if it does not win.”

THE AUTHORITARIAN TRANSITION TOWARD DEMOCRACY

And here’s another paradox, about which there is no agreement either, namely, that democracy was achieved before peace. I have argued that this transition was contradictory, for the construction of a democratic regime took place even when the repression was still fierce. In 1983, the illegitimate government of General Efraín Ríos Montt laid down electoral and political party laws. The following year, the equally illegitimate government of General Óscar Humberto Mejía Víctores applied these laws, calling for a Constituent Assembly, which in 1985 signed a National Constitution into law. He also called a presidential election, which was won by civilian lawyer Vinicio Cerezo.

Both processes were free, without fraud, with limited pluralism, but in the overall context of terror. For the first time since 1951, there was uncertainty about who would win. All the candidates were civilians of varied ideologies. The rightist military government turned over power on March 15, 1986, to a civilian who espoused a center-left ideology. But the homicide continued.

It seems to make logical sense that the end of the war comes before free elections, as has happened in a number of African countries. There, faced with a dynamic of death, it was only after reaching the difficult moment of a “ceasefire” that peace agreements were reached, and only then did elections take place. In Guatemala, two democratic elections were held before the URNG announced a ceasefire in March 1996, which was then accepted by the government.

The explanation for why a return to democracy came before an end to the terror can be quite convoluted, but let us start with something basic. An electoral process can be categorized as democratic when several independent political parties, of diverse ideologies and histories of opposition to the military, compete against each other. The winning party, the Christian Democratic Party, situated on the timid left in Guatemala, garnered 38% of the total vote. This was the first election without fraud in more than thirty years.

It was not a transition that came about as a result of an agreement; rather, it was imposed from above. Elections under illegal and authoritarian governments do not usually result in democratic governments, so why was there an authoritarian transition to political democracy in Guatemala?

At least three different events took place simultaneously, which I evaluate with different degrees of importance. First, the elections formed part of a counterinsurgency strategy, conceived of and applied by U.S. policy; the objective was to legitimize the regime against which the armed insurgency was fighting. After the elections, the guerrillas would be taking up their arms against a freely elected civilian government and not against a military dictatorship.

Second, the army had destroyed the guerrillas’ headway, which it termed a strategic defeat for the insurgents. Finally, the military leadership suffered internal decomposition, with military coups in which generals were pitted against one another in March 1982 and August 1983. On both occasions, coup leaders offered, as a pretext for their taking power, a “plan for immediate democratization.” The military had lost prestige because of their well-known human rights violations and open corruption. Several officials had amassed wealth through common crime, particularly crime linked to drug trafficking.

TAKING THE “FISH OUT OF THE WATER”

Guatemala is a nation with an important indigenous population of Maya origin. Perhaps what most impressed me on my return to Guatemala were the crowds of indigenous people on the streets of the capital, their social participation and an abundant documentation that went much further than folklore. I worked for the Historical Clarification Commission and spent my days reading about the genocide that had been committed by the army. These were killings with racist roots and, some colleagues say, they were preceded by an indigenous rebellion. If that really did occur, it would be as a result of an awakening of indigenous consciousness, the mobilization of several communities and the decision of those communities to join the struggle alongside the guerrillas.

The guerrillas modified their program to recognize that indigenous people had their own cultural ways and their own struggles, that they weren’t just peasants. Class and ethnicity are not opposing categories, and cultural identity is compatible with class consciousness. The core of the Guatemalan revolution, according to a guerrilla document, is constituted by the indigenous and peasant masses since they are the majority and the most exploited.

It has been documented that many activists approached indigenous communities in the northwest region of the country and that tens of thousands of indigenous people expressed their “sympathy” towards the insurgents. Tales about this mutual rapprochement abound, full of examples of logistical support from the indigenous community and indoctrination on the part of the insurgents. This growing closeness took place in the national context of armed struggle in which the important thing was training and organization for war; the inherent dynamic of the moment was to arm for self-defense. But I have not been able to find any information about indigenous columns in battle or high-level indigenous commanders, or whether they were armed. Indigenous mobilization was easily detected by military intelligence, interpreted as a grave threat, and destroyed on a scale without parallel in Latin America. The guerrilla comandantes did not foresee the massacres, and therefore could not stop them.

Although many do not agree with me, I firmly believe that there was no indigenous rebellion; there was a slaughter of indigenous people. In the second half of 1981, the armed forces put into effect an operation they called “scorched earth.” It was a victory of the army over unarmed peasants. Again, it is difficult to calculate the number of victims. The UN Historical Clarification Commission counted some 80,000 dead, more than 600 villages destroyed; more than half a million refugees and displaced people.

Certainly the massacres of the 1980s were a continuation of colonial genocide. It is shocking that 51% of those killed were in groups of more than 50 persons and that 81% of these were identified as indigenous. General Héctor Alejandro Gramajo, Army Chief of Operations in 1982, explained the operation by saying: “We only wanted to take the fish out of the water…we think we were successful; we left the fish without water.”

SICK STATE, FAILED STATE?

All that I have described ever too briefly in the previous paragraphs has made it very difficult for Guatemala society to function. The legacy of violence is all too apparent. At the beginning of May 2010, there was a riot in Boquerón, a high-security prison in a southeast region of the country. The prison was seized by 200 gang members serving prison sentences. Interior Ministry authorities had to negotiate with the chief of the “maras,” as the gang members are known, giving in on several points and recognizing the maras’ power. More or less around the same time, the Finance Ministry negotiated a fiscal reform for the millionth time with the board of CACIF, a conglomerate of powerful businessmen. And at the end of the same month, the rector of the University of San Carlos and its Superior Council had to negotiate with a student faction that had impeded the operations of the state university for ten days.

There is heated discussion about whether present-day Guatemala can be considered a failed state. In the rhetoric of those who combat violence internationally, a state fails when it has lost control over the legitimate monopoly of violence, or when social relations are ruled by an anti-state logic.

In effect, in Guatemala, the forces of “narcobusiness” controlled several municipalities in regions sharing a border with Mexico, such as San Marcos and Huehuetenango, or sparsely populated regions such as Petén. Various forms of criminal power have emerged there, as well as in regions that have experienced recent agricultural modernization such as Alta Verapaz and Zacapa. Since 2001, criminal organizations with their own “legality” and peasant support have replaced the authority of the state. It seems inevitable that in the face of the current insecurity that plagues citizens, they would respond with another rationalization: to confront private crime, we need private security. There is now a free market of 140 security agencies, most of them legally registered, with at least 65,000 guards, bodyguards and watchmen, all of them armed and poorly trained. At present, the National Police have 20,000 police officers.

In Guatemala, the symptoms of collective anomie—normlessness—are emerging, predicting that this will become a sick society, with elementary sociability decomposing in an extreme form. It is not easy to explain why twenty people are killed every day when there is no civil war; that 750 cars are stolen every day—where are they all hidden? Some 8,000 extortions take place daily in the marginal neighborhoods, proving that the poor prey more on their equals than anyone else.

And yes, with urban robberies, highway assaults, kidnappings, the number of crimes increases, the number of delinquents increases, and no one imagines that there’s an end to it. Carlos Castresana, then director of CICIG, a UN agency that helps with criminal investigations, declared in a March conference in the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO) that Guatemala had the greatest per capita concentration of firearms in the world, with the exception of the Middle East.

In the last five years, the dark figure of the hired hit man has appeared. These are people—often poor youngsters—who are contracted in the free market to kill for a price. On April 28, a 15-year-old boy killed a woman with a single shot. For this job, he was paid the equivalent of $13. Only 3% of crimes denounced to the Public Ministry ever get to trial. The serious thing about this rampant crime wave is the inability of the state to control it. In the last two years, two high-ranking officials of the National Police have been publicly dismissed and brought to trial for participation in drug trafficking rings. About a quarter of the police force has been dismissed for various types of corruption. One moves about in a very insecure society with a weakened public authority and a citizenry that is losing its confidence in the government and in the future.

Guatemala, Guatebuena, Guatemaya

Por Edelberto Torres-Rivas

Es un paisaje más que una nación, me dijo un amigo, cuando volvía a Guatemala en septiembre de 1996 y después de treinta años de irregular ausencia. Del país recordaba todo, o casi todo lo que en esa época sin Internet se podía saber: matanzas, democracia, militares, guerrilla, elecciones… En el último minuto, antes de aterrizar en La Aurora, tenía en la mano un folleto con propaganda turística y una novela de Miguel Angel Asturias. Una hermosa realidad hecha comercio para atraer gringos y una fantasía escrita, a través del océano de su palabra, para llegar a otra realidad, el mundo indígena. En el trifoliar, el lago de Atitlán aparecía pegado con agua verde a sus tres volcanes, Tolimán, Atitlán y San Pedro, todo lo cual según dicen, constituye uno de los lugares más bellos del mundo. Y no lejos de Panajachel, la novela se desarrolla en San Martín Chile Verde, la historia de Celestino Yumi, indio quiché que vendió su mujer al diablo Tazol, solo para enredarse en los abismos de ‘la mulata de tal’, talvez la mejor novela de nuestro Miguel Angel. Poco tiempo después, supe que en las riberas del lago y en San Martin, hubo muchos muertos, gente del lugar, guerrilleros, soldados.

“…GUERRILLA QUE NO PIERDE, GANA”

Ese, 1996, fue un año especial; estaba finalizando lo que la historia oficiosa continúa llamando el “conflicto armado interno”, que habría empezado, según algunos, en 1954 cuando Árbenz renunció bajo presión norteamericana; o según otros, en 1964, cuando la influencia cubana cobró forma de guerrilla porque centenares de jóvenes que con mas convicciones que fusiles se fueron a la montaña. A mi, todavía me tocó vivirlo, por lo que creo que el fratricidio empezó con la revuelta urbana de marzo y abril de 1962. En las calles de la Capital, la policía militarizada y el ejército mataron mas de cincuenta manifestantes. En esa fecha apareció el teniente Yon Sosa, pues en Guatemala fueron militares los primeros guerrilleros, jóvenes rangers que organizaron el Movimiento 13 de Noviembre.

Con varios amigos estuvimos en la Plaza de la Constitución. La ceremonia de la firma del Acuerdo de Paz Firme y Duradera fue en el Palacio Nacional, a donde llegaron los generales, los políticos, los comandantes, y un público selecto. Era una noche fría, el 29 de Diciembre de 1996, y atrás quedaban treinta y cuatro años y dos generaciones de gente lastimada por el terror. Cifras menos o cifras más, unos 150 mil muertos que me hicieron recordar lo que dijo Stalin con criminal cinismo, una persona es un crimen pero muchas ya son sólo estadísticas.

Es doloroso pero cierto, cuando se contabilizan los muertos por decenas de miles, la precisión no importa. Talvez los porcentajes dicen más: el 92% de las víctimas fueron civiles ajenos a los frentes de combate; un 54% fueron menores de veinticinco años y un 12% mujeres violadas o ultrajadas de diversas maneras.

Me he permitido disentir por escrito y en debate oral, en este país no hubo guerra civil. Hubo una permanente represión del Estado, castigando todo lo que fuera considerado pensamiento o acción de la oposición política, vida o gesto sospechoso. Esto calificó el accionar militar con la lógica de la guerra y lo que resultó fue la destrucción sistemática de centenares de dirigentes sindicales, campesinas, estudiantiles. Esto ocurrió durante tres décadas.

En el interior de este tiempo histórico, se produjeron dos momentos guerrilleros. Uno, sucedió entre 1965 y 1968 y terminó pronto, en medio una gran confusión; fue una reproducción de la teoría del ‘foco’, que el Che Guevara elaboró como modelo de guerrilla. El otro, diez años después, (1980-83), se planteó la estrategia de ‘la guerra popular prolongada’, a la manera vietnamita. La ofensiva insurgente, en 1981, fue destrozada por el ejército, mejor armado y organizado.

Me he permitido opinar que la URNG sufrió una derrota militar estratégica de la cual no se repuso. La insurgencia tuvo una vida militar breve pero políticamente larga. Una polémica presencia que les permitió sobrevivir hasta 1996, negociar con tres gobiernos sucesivos y suscribir sustantivos acuerdos de largo alcance. ¿Cómo calificar, como síntesis, lo que sucedió entre 1962 y 1996? Es oportuno recordar lo que sentenció Mr. Kissinger, ‘que guerrilla que no pierde, gana; y ejército que no gana, pierde.’

LA TRANSICIÓN AUTORITARIA A LA DEMOCRACIA

Y ocurrió otra paradoja, acerca de la cual tampoco hay acuerdo, pues antes de alcanzarse la paz se logró la democracia. He sostenido que fue una transición contradictoria pues la constitución del régimen democrático sucedió cuando la represión aún era feroz. En 1983, el gobierno ilegal del general Ríos Montt, elaboró las leyes Electoral y de Partidos políticos. En 1984 el gobierno también ilegal del general Mejía Víctores aplicó tales leyes convocando una Asamblea Constituyente, que en 1985 promulgó la Constitución Nacional. También convocó a elecciones presidenciales que ganó el abogado Vinicio Cerezo.

Ambos procesos fueron libres, sin fraude, con un pluralismo limitado, pero en el seno del terror. Por vez primera, desde 1951, hubo incertidumbre por el ganador, solo hubo candidatos civiles, de diversas ideologías. Y un gobierno militar de derecha, el 15 de marzo de 1986, entregó el mando a un civil de centro-izquierda. Pero el homicidio continuó.

Hay un sentido de la lógica histórica en que el fin de la guerra antecede a las elecciones libres, como ocurrió en esta época en varios países africanos. Allí, enfrentados con una dinámica de muerte solo después de alcanzar el difícil momento del ‘alto del fuego’, llegaron a acuerdos de paz y, solo entonces acordaron la contienda electoral. En Guatemala hubo dos elecciones democráticas antes que la URNG anunciara el alto al fuego (marzo 1996) y el gobierno lo aceptara.

La explicación puede llevar al absurdo pero ella empieza con algo elemental: califica como democrático un proceso electoral cuando compiten diversos partidos independientes, portadores de ideologías diferentes, e historias de oposición a los militares. Ganador, el Partido Demócrata Cristiano, en Guatemala situado a la izquierda temerosa, obtuvo el 38% del total. Fueron las primeras elecciones sin fraude en más de treinta años.

No fue una transición pactada sino impuesta. Las elecciones bajo gobiernos ilegales y autoritarios, por lo general, no producen gobiernos democráticos, salvo en circunstancias especiales. ¿Por qué aquí ocurrió una transición autoritaria a la democracia política?

Hubo al menos tres hechos concurrentes, que valoro personalmente con diversa magnitud. Primero, las elecciones formaron parte de una estrategia contrainsurgente, concebida y aplicada por la política norteamericana; el objetivo era legitimar al régimen frente al cual se alzaba la insurgencia armada. La guerrilla luchaba ahora contra un gobierno civil, surgido de elecciones libres y no frente a una dictadura militar.

En segundo lugar, el ejército había destrozado la iniciativa guerrillera, en lo que se calificó como una derrota estratégica; y por último, la cúpula militar sufrió una descomposición interna: sucesivos golpes, ¡generales contra generales! en marzo de 1982 y agosto de 1983. En ambas ocasiones, los golpistas ofrecieron como pretexto un ‘plan de democratización’ inmediato. Los militares estaban desprestigiados por sus conocidas violaciones a los derechos humanos, había en su interior una abierta corrupción. Varios oficiales habían derivado al crimen común, con vínculos con el narcotráfico.

COMO QUITAR EL “AGUA AL PEZ”

Guatemala es una nación con una importante población indígena, de origen maya. Probablemente lo que más me llamó la atención al volver a Guatemala fue la muchedumbre indígena en las calles de la ciudad, su participación social, una abundante bibliografía que ya no era folclore. Trabajé en la Comisión de Esclarecimiento Histórico y pude leer sobre el genocidio cometido por el ejército. Fue una matanza de raíz racista que según algunos colegas estuvo precedida con lo que califican como una rebelión indígena. Si así ocurrió, ella seria el resultado de un despertar de la conciencia indígena, de la movilización de numerosas comunidades y la decisión de incorporarse a la lucha junto a las guerrillas.

El programa de la guerrilla rectificó al reconocer que los indígenas tenían rasgos culturales y reivindicaciones propias, no solo eran campesinos. Clase y etnia no son categorías opuestas; y la identidad cultural es compatible con la conciencia de clase. El eje de la revolución guatemalteca, dice un documento, lo constituyen las masas indígenas/campesinas, porque son mayoritarias y las mas explotadas.

Se ha documentado que numerosos activistas se ‘aproximaron’ a las comunidades indígenas del nor-occidente del país y decenas de miles de indígenas expresaron su ‘simpatía’ por los insurrectos. Es abundante el anecdotario de ese mutuo acercamiento, pleno de ejemplos de apoyo logístico por parte de los indígenas e indoctrinamiento por parte de los alzados. Esta aproximación ocurría en un escenario nacional de lucha armada, en que lo sustantivo era el entrenamiento y la organización para la guerra; en que la dinámica inherente al momento era armarse para defenderse. Pero no he encontrado información si hubo columnas indígenas, o comandantes de alto nivel, o si estaban armados. La movilización indígena fue fácilmente detectada por la inteligencia militar, interpretada como una grave amenaza y destruida en dimensiones sin paralelo en América Latina. Los comandantes no previeron la matanza, y luego, no la impidieron.

A contrapelo de una fuerte opinión en contra, yo afirmo que no hubo una rebelión indígena; fue una matanza de indígenas. En el segundo semestre de 1981 las fuerzas armadas desencadenaron una operación calificada como tierra arrasada. Fue una victoria del ejército frente a campesinos inermes. De nuevo es difícil precisar el número de víctimas; la Comisión de Esclarecimiento Histórico (Naciones Unidas) denunció unos 80.000 muertos, cerca de 600 aldeas destruidas, más de medio millón de desplazados (internos) y refugiados (en el exterior)

Existe la certeza que las matanzas de los ochenta son continuación del genocidio colonial. Es estremecedor constatar que el 51% de asesinados estaban en grupos de mas de 50 personas y el 81% identificados como indígenas. El General Alejandro Gramajo, jefe de operaciones del ejército en 1982 explicó el operativo diciendo que: “solamente queríamos quitarle el agua al pez…Creo que tuvimos éxito, los dejamos sin agua…¡”

¿SOCIEDAD ENFERMA, ESTADO FALLIDO?

Todo lo que tan brevemente se reseña en los párrafos anteriores, ha determinado un funcionamiento difícil de la sociedad guatemalteca. A comienzos de mayo de 2010, hubo un motín en la cárcel de alta seguridad, el Boquerón, en el sur oriente del país; fue ‘tomada’ por unos 200 pandilleros allí detenidos. Las autoridades de Gobernación tuvieron que negociar con los jefes de las ‘maras’, cediendo en algunos puntos y reconociendo su poder. Más o menos en la misma fecha, el Ministro de Finanzas negociaba por enésima vez con los directivos del CACIF (altos empresarios) una reforma fiscal. A fines del mismo mes, el Rector de la Universidad de San Carlos y su Consejo Superior (Universidad estatal) tuvo que negociar con una facción estudiantil que impidió durante diez días el funcionamiento normal.

Se discute vivamente si ya se descendió a lo que en la retórica del combate internacional a la violencia llaman el Estado fallido. Ello ocurre cuando el Estado ha perdido el control sobre el monopolio legítimo de la violencia. O las relaciones sociales se rigen con una lógica anti estatal.

De hecho, en Guatemala, las fuerzas del narconegocio controlan numerosas municipalidades en regiones fronterizas con México (San Marcos, Huehuetenango) o en regiones poco pobladas y hasta hace poco mal comunidadas (Petén). Allí, o en sitios de reciente modernización agrícola (Alta Verapaz, Zacapa), han surgido desde 2001 formas de un poder criminal, con su propia legalidad y con apoyo campesino, que reemplazan la autoridad del Estado. Pareciera inevitable que frente a la creciente inseguridad que golpea a las ciudadanos, otra racionalidad se imponga: ¡frente al delito privado la seguridad privada! Hay en el mercado libre unas 140 agencias de seguridad, la mayor parte sin inscripción legal, que cuentan por lo menos con unos 65.000 guardias, guardespaldas, vigilantes, todos armados y poco entrenados. La Policía Nacional tiene a la fecha, 20,000 agentes.

En Guatemala se descubren los síntomas de una condición de anomia colectiva, que aproximan el diagnóstico a lo que sería una sociedad enferma, a formas agudas de descomposición de la sociabilidad elemental. No es fácil responder por qué hay ahora una tasa de veinte homicidios diarios, sin guerra interna; setecientos cincuenta automóviles robados por mes ¿dónde se ocultan?; unas ocho mil extorsiones todos los días en barrios marginales, que prueban que los pobres a quien más castigan es a sus iguales.

Y así, robos urbanos, asaltos en las carreteras, secuestros; los delitos aumentan, crece el número de delincuentes y nada permite suponer que se ha ‘tocado techo’. El Dr. Castresana, Director una agencia de Naciones Unidas de ayuda en la investigación penal, declaró en FLACSO (21/III/10), que Guatemala tiene la mayor concentración de armas de fuego en el mundo por persona (con excepción del Medio Oriente.

En el último quinquenio apareció la sombría figura del ‘sicario, el que mata por contrato en un mercado libre. Un niño de 15 años, el 28 de abril de este año, mató de un balazo a una señora por lo cual cobró un equivalente de 13 dólares. Solo el 3% de las denuncias de delitos en el Ministerio Público llegan a juicio. Lo grave de este desborde criminal es la incapacidad del Estado para controlarlo. En los dos últimos años han sido públicamente destituidos y enjuiciados dos altos jefes de la Policía Nacional que formaban parte de una estructura de narcotraficantes. Un 25% de policías han sido destituidos por distintas formas de corrupción. Se transita en una sociedad muy insegura, con la autoridad pública disminuida y una ciudadanía que pierde la confianza en los poderes públicos y en el futuro….

El lago de Atitlán también se enfermó con una bacteria resultado del cambio climático; el turismo ya no llega a uno de los lugares más hermosos del planeta. Pero hay esperanzas de curar el Lago, no todo está perdido. También la sociedad guatemalteca saldrá adelante. Muchos luchamos por que así sea.

Related Articles

Guatemala: Editor’s Letter

The diminutive indigenous woman in her bright embroidered blouse waited proudly for her grandson to receive his engineering degree. His mother, also dressed in a traditional flowery blouse—a huipil, took photos with a top-of-the-line digital camera.

Making of the Modern: An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann

Making of the Modern An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1Related Articles

Increasing the Visibility of Guatemalan Immigrants

Guatemalans have been migrating to the United States in large numbers since the late 1970s, but were not highly visible to the U.S. public as Guatemalans. That changed on May 12, 2008, when agents of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) launched the largest single-site workplace raid against undocumented immigrant workers up to that time. As helicopters circled overhead, ICE agents rounded up and arrested …