Fostering Child Wellbeing

Integrating Mental Health and Health with a Children’s Rights Perspective

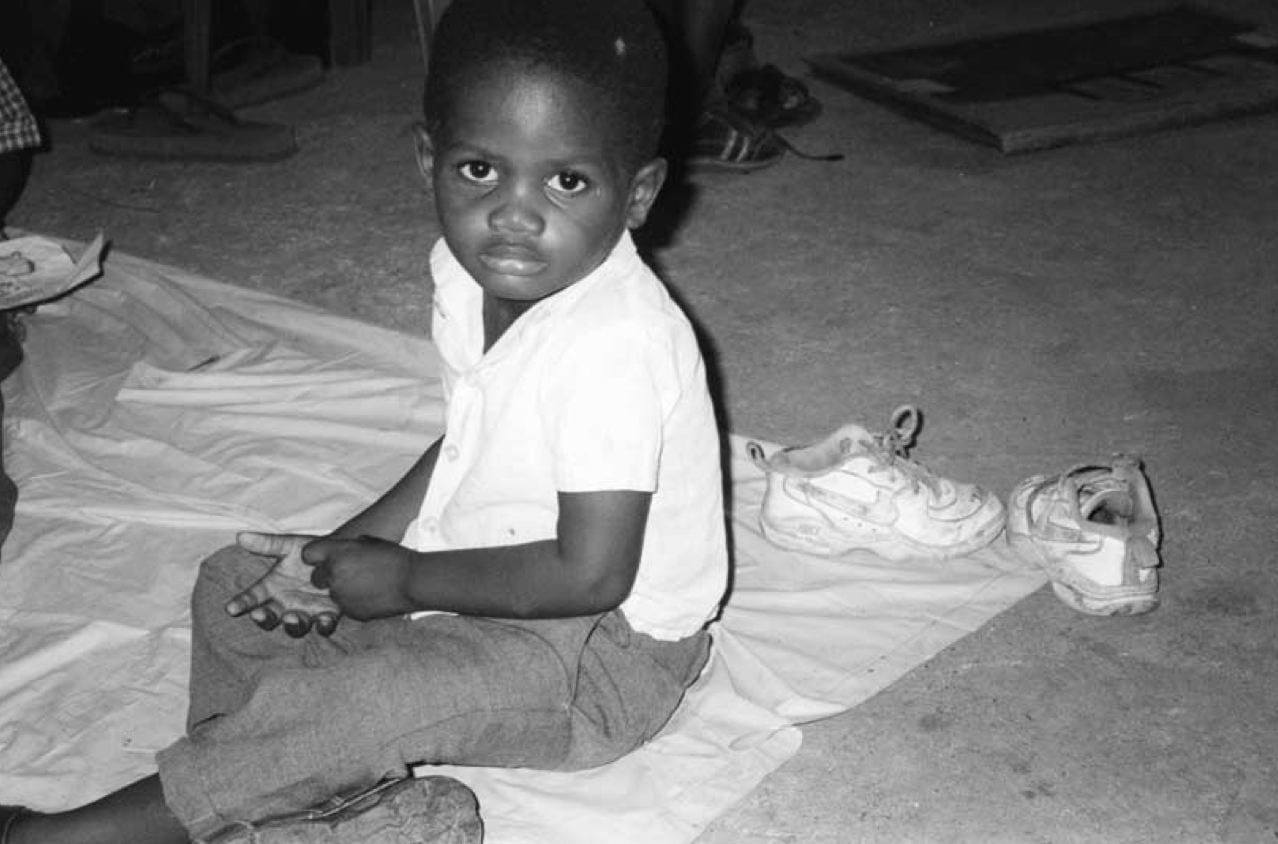

A child and his shoes on the Dominican border. Photo by Daniela Helen Tartakoff

Children sleep and work on the streets of many countries in the Western Hemisphere. They die too young. Injuries to children—whether intentional or not—exceed those in much of the rest of the world. Often, kids either don’t get enough to eat or are not fed nutritious food. Substance abuse is a fact of life throughout Latin America. The stark reality of life for children in the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean brings home both the challenge and the opportunity for those of us concerned with children’s health in the area. Projects in Chile, Jamaica, Costa Rica and Brazil are now seeking to make a difference by connecting rights-based public policy concerns with the more typical health agenda.

Nations in both Latin America and the Caribbean provide fertile ground to demonstrate how to achieve better developmental outcomes for children. From the region, it is hoped that successful initiatives will gain the attention and support of international health agencies, governments, communities, stakeholders and families.

It is true that child wellbeing dramatically improved during the 20th-century. Indeed, several Latin American and Caribbean countries have had particularly striking improvements in the past decade. These changes have shifted the emphasis from enhancing child survival rates to finding ways to enhance the healthy development and wellbeing of the world’s children.

Yet, when faced with overwhelming health and mental health problems, how can responsible individuals think beyond direct assistance as a way of helping the growing number of children who survive beyond age five? Programs providing food or clinical intervention do change children’s lives. The roots of the problem must be addressed; evidence from many parts of the world clearly shows that development and implementation of policies and programs attacking root causes are the way out of dire straits. These programs can impact social ecology and advance health and mentalhealth agendas. They can identify specific problems and solutions and allocate appropriate resources.

Our focus must shift from the more traditional concern with survival and disease. This can only be achieved if new ways to collaborate can be demonstrated, new knowledge can be shown to make a difference in programs and policies, and new resources can be activated and used effectively to achieve child health and wellbeing. Resources currently exist in all domains that can demonstrate innovative ways to achieve these goals. The academic community, health organizations, other systems serving children and youth, and “the community” in Latin America and the Caribbean are some examples. Support from the community is essential for the success of this venture. The traditionally strong role of the family and community infused with new ideas will enable the development of novel strategies that may have broad applicability, replicability and implications for policy.

Recently, the Mental Health and Special Programs Unit of the Technical Services Health Area and the Child and Adolescent Health Unit of the Family and Community Health Area of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS), the Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence at the World Health Organization in Geneva and faculty from Harvard and Columbia universities collaborated to focus on the healthy development and wellbeing of children, rather than the more traditional emphasis on pathology associated with most other academic collaborations. PAHO is committed to achieving a better understanding of how new knowledge can be coupled with advocacy to demonstrate the potential for enhancing the health and mental health of children in Latin American and the Caribbean. Fostering collaboration among mental health and child health colleagues is an essential ingredient of this initiative. This collaboration seeks to integrate new knowledge with policy development in an innovative way to rethink and reorient health strategies. A key aspect of academic participation is the support for gathering data on the extent of the problem by utilizing the existing resources in a precise manner.

The initiative, hosted by DRCLAS, brought together participants with a wide range of skills—whether clinical, sociological, behavioral and epidemiological—that raise the level of dialogue. This dialogue can be utilized to develop imaginative programs aimed at influencing the social ecology in ways that enhance child-related outcomes. The group and the initiative share a common belief that merging an understanding of social ecology and clinical knowledge in community-based research will lead to improved policy development, advocacy, and model program dissemination. All involved recognize the need for solid evidence of efficacy and effectiveness derived from research to convince policymakers of the importance of a plan to enhance child wellbeing which integrates early child development, child health and child mental health initiatives in a public health context.

The collaboration did not start with any preconceptions of the “right” way to approach a set of identified problems, but rather took root in existing, nascent programs. These programs demonstrated principles of organization, intervention and policy with a likelihood to compel notice by public policy makers and colleagues in the early child development, child health and mental health fields of study. At the core of these diverse initiatives lies a belief in the potential of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child to foster the improvement of children’s lives and influence policy. The Convention has been embraced to a remarkable degree in Latin America and the Caribbean despite economic hardship and political turmoil. The models, once implemented, will demonstrate how to use the Convention to the maximum benefit of children’s health and mental health. Despite inequalities both within countries and between countries, each country has assets that can improve the wellbeing of children through effective policy-making.

The overall notion that policy is a key vehicle to improving the lives of children comes from the conceptual model of Dr. Julius Richmond, Harvard professor emeritus and former Assistant Secretary of Health and Surgeon General of the United States. Dr. Richmond has shown the powerful interaction of “knowledge base,” social factors, political will and, ultimately, public policy. For the purposes of the present collaboration, the model is modified to identify specific policy impacting early child development and mental health promotion, and the development of community interventions as its social strategy.

The group identified four projects, which although of diverse natures, all had a common focus on child wellbeing, theoretical framework, use of community interventions, their policy relevance, ability to be replicated and research rigor. Each project benefits from an experience, sometimes not well documented, that has identified problems or strengths in implementation, applicability to target groups and the potential to be incorporated in policy development and community interventions.

In Brazil, the impact of Guardianship Councils on child wellbeing will be studied. Guardianship Councils are a direct outgrowth of the Brazilian government’s ratification of the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child—which thus far, has had a dramatic impact. Legislation recognized all children as citizens, not just those who violated the law as was previously mandated. With this policy, children were accepted as individuals with their own interests who should be treated as agents in society and not as passive recipients of philanthropic actions. The legislation led first to the establishment of Child Rights Councils with macro-level responsibilities and the Guardianship Councils which functions at the community level and ensures that children in need or at risk receive the best possible assistance. Councils can now be found throughout Brazil. While the distribution is wide, the impact of the Councils and their functioning remains obscure to many. The purpose of the pilot research will be to document the impact of the Councils on children’s health and wellbeing. The study will determine the factors that support the existence of the Councils, examine correlates and changes of child health and wellbeing associated with the actions of the Councils, and study the nature of linkages with other segments of the health and child-services sector.

In Costa Rica, the impact of maternal depression on the development of children will be studied. This builds on the well-documented positive impact of considering the family as a unit of intervention in which all risk factors are intertwined. This model, developed by Professor William Beardslee of Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital, has shown that when parents are depressed, their children are affected in various ways and by different mechanisms. Untreated maternal depression may lead to developmental distortions and, eventually, less than optimal overall development. The research in Costa Rica, in collaboration with Dr. Luis D. Herrera, will demonstrate the applicability of the model, adapted for use by clinicians in Costa Rica, for Latin American families and provide an enhanced understanding of the impact of culture and poverty, both key elements in appreciating the relevance of social ecology. The intervention also involves a psycho-educational preventive, that is, literally teaching individuals and families about depression and what can be done to lessen its impact.

In Jamaica, the project will focus on extending the findings of the Profiles project, which used community interventions to improve child developmental and behavioral outcomes over an extended period of time. Having already identified family and community factors that affect developmental outcomes by age six, there is now an opportunity to understand the impact of interventions at a later age and to focus on the policy relevance of the Profiles project. This project can demonstrate the linkages or non-linkages between the social environment of the child and family and an optimal developmental outcome, as measured by school achievement.

In Chile, the pilot project builds on evidence that integrated health interventions can transform the life experience of children and lead to improved developmental outcomes. The conceptual framework is derived from Healthy Steps, which provides family support and education related to child development. The project will deliver comprehensive and developmentally-oriented health care in a middle-income society that has been impacted by structural realignment. Structural realignment refers to the economic changes associated with reforms urged by the World Bank in Chile. The research will assess the effectiveness of integrated health management programs for children under three-years-old as a community child mental health program compared to those currently in place. The project underscores the importance of embedding an appreciation of the role of risk, protective factors and a life course perspective to achieve the desired outcome of child wellbeing. The project also highlights the importance of family and community contexts as well as the role of the State through policy. Cost and cost effectiveness, key issues for policymakers, will be studied.

Thus, quite different projects, with conceptual frameworks that embrace common principles and objectives, will be able to demonstrate the importance of a rightsbased perspective on health and mental health. The impact of this focus should be evident through enhanced access, increased capacity for intervention and policy development. All of the projects have specific policy relevance in their countries, but offer the possibility for informing policy development throughout the region. The traditional focus on family and community in Latin America and the Caribbean make it a fertile ground for studying the impact of community-focused programs and may offer models applicable throughout the world. The elaboration of an understanding of families and communities will demonstrate the importance of valuing social ecology.

Winter 2004, Volume III, Number 2

William R. Beardslee(Harvard Medical School, Children’s Hospital Boston, Paula Bedregal (P. Catholic University of Chile), Myron L. Belfer(Harvard Medical School, World Health Organization), Mary Carlson (Harvard University), Cristiane Duarte (Columbia University), Felton Earls(Harvard Medical School), Luis D. Herrera (Fundacion Paniamor, Costa Rica), Christina W. Hoven(Columbia University), Raul Mercer (Center for Studies of State and Society, Argentina), Claudio T. Miranda (Pan American Health Organization), Helia Molina (Pan American Health Organization), James M. Perrin (Massachusetts General Hospital for Children) and Maureen Samms- Vaughan(University of the West Indies) contributed to this report, which was authored by Myron Belfer with Raul Mercer and James Perrin. They can be reached through Claudio T. Miranda at mirandac@paho.org.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: The Children

A blue whale spurts water joyfully into an Andean sky on my office door. A rainbow glitters among a feast of animals and palm trees. Geometrical lightning tosses tiny houses into the air with the force of a tropical hurricane.

Centroamerica

Cuando Pedro Pirir, fue despedido del taller mecánico donde trabajaba desde hacía muchos años, experimentó una sensación de injusticia y pena que luego se transformó en una voluntad…

Irregular Armed Forces and their Role in Politics and State Formation

As I sat in heavy traffic in the back of a police car during rush hour in the grimy northern zone of Rio de Janeiro, I studied the faces of drivers in neighboring cars, wondering what they thought of…