Frontiers in Latino Popular Music

The importance of Latino Popular Music cannot be overemphasized, as the United States grapples with half a million Dominicans and 35 percent of Puerto Ricans living in New York, with an increasingly “Latinized” Los Angeles, and a myriad of new and established populations of Hispanic origin in small and medium sized cities throughout the nation. Deep and complex musical traditions have evolved together with these demographic transformations.

In the fall semester, Visiting Professor of Ethnic Studies, Romance Languages and Literatures and Music Deborah Pacini offered a new course entitled Latino Popular Music in both the Music Department and the Extension School at Harvard. The course examines the continuum in musical styles that have linked communities in the United States with their Latin American origins since World War I. In a rich exploration of musical expressions ranging from salsa to Chicano rock, Pacini has brought to light an important new cultural theme in American society, and one increasingly relevant to a growing number of students at Harvard.

As Pacini and invited speaker Paul Austerlitz, a specialist on Dominican merengue, pointed out, the definition of popular musical styles is never finite. They are forms of expression created in communities in constant flux, and increasingly throughout this century, through migration and transculturation. Syncretism dominates much of the music discussed in the class, while at the same time, individual styles such as Central American and Mexican cumbia, New York and Miami salsa, and danza, jÃbaro, bomba and plena, are explored for their indigenous and social roots in race, class, migration, and history.

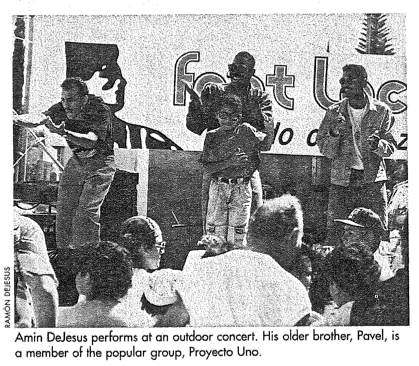

Pacini’s course demonstrates how different musical styles each have their own stories, as in narcorridos, which emerged from border stories of smuggling and trafficking, and which have become legendary in Los Angeles. In the United States, many styles are inherently urban, as in the case of rap, but others maintain their rural roots. The children of Latino families may not speak Spanish, and often reject what they see as the outdated styles of their parents. However they often form new identifications in musics like banda and hip hop. The music explored is both hybrid and pure: black, white, and brown, linked to multiple ethnic constructions, like Puerto Rican, Dominican, Mexican, and finally, as Pacini herself has explored, in the newest amalgam of world music. In her lecture on Dominican bachata, Pacini ended the class with a recording of a New York-based bachata rendition of Diana Ross’s classic “Killing Me Softly,” with rap lyrics, a perfect symbol of the evolving nature of Latino musical experience in the United States today.

Latino Popular Music examines musical styles and aesthetics, along with the music industry, issues of commercialization, and complex questions of authenticity. At the same time, as in the case of bachata, which still retains a distinctly local flavor in the Dominican Republic, Pacini’s course highlights the importance of musical styles that continue to resist homogenization.

The distinctions in popular musical cultures between the East and West Coast form a central theme in Pacini’s course, although there is much evidence of ongoing cross-fertilization. In New York and Los Angeles, music is a cultural and a social phenomenon. One of the highlights of the course is the focus on Latin music in Los Angeles, ranging from traditional Mexican styles to newer songs of outspoken social criticism, as in the trenchant lyrics of the group Los Illegals.

As part of the class, Caprice Corona (’97) delivered a guest lecture on the social significance of Latino rap and hip hop in Los Angeles, based on her senior thesis, which she wrote as a joint concentrator in Anthropology and Music. Rap and hip hop arose in urban Latino and African American communities in the 1970s and 1980s, in a period of rising unemployment. For Corona, a third generation Mexican American from Sacramento, California, music, break dancing, and art are all ways in which Latino and African American youth reappropriated cultural space for themselves, to counter growing economic and social marginalization.

One of the most interesting findings in her research was the very fluidity of ethnic and racial identifications. Groups such as Delinquent Habits dress like Mexican cholos, and sing lines like “It wouldn’t be L.A. without Mexicans.” Its singers, though, include only one Mexican; the others call themselves the “Blaxican” (Black and Mexican) and the “guero loco,” or the crazy white guy. The Cyprus Hill group consists of a Cuban, an Italian (from New York) and a Cuban/Mexican singer. Still these groups are, in Corona’s words, “adamant in portraying their Latino-ness,” even though they may not aim for an exclusively Latino audience.

Rap lyrics come in many layers, incorporating Spanish and English, Spanglish, and in California, ethnically charged words like those in Nahuatl, in a music that Corona describes as “thick with cultural references.” Like many forms of popular music, rap and hip hop were originally shunned by both television and radio, only later to be accepted in more “marketable” forms, a phenomenon that raises difficult issues of crossing, authenticity, and purpose.

The untangling of social, racial and ethnic identities and cultural inclusion and exclusion are themes in the course, which offers students a forum to discuss and compare their own experiences alongside more scholarly studies. Students in the course, which requires fieldwork on an aspect of Latino popular music in Boston, bring an enormous breadth of experience and knowledge to the class. Their research includes topics such as Latin jazz, gender-based perceptions of dance floor etiquette in salsa, and a study of the local market for Latin music. The course serves as a stimulus for further research in a field that virtually all authors agree remains seriously understudied.

Students in Latino Popular Music are musical activists and participants, keen observers, and members of a new generation of musical cultures dynamic in their evolution. In discussions, readings, and recordings, they explore the meaning of the varied and collective “we” that is called Latino. Beyond affirming identities, we learn that there are new questions emerging in music, about ambiguity, class, and social and cultural aesthetics that affect Latino and non-Latino musical creators and consumers today.

Winter 1999

Hilary Burger recently completed her PhD in Latin American History at Harvard.

Related Articles

Linking Latin America

I have captured images of such seemingly disparate subjects as Mennonite immigrants to Mexico, Latina contestants for Selena standings, the Pope in Cuba, and traditional Sunday serenatas…

A Violence Called Democracy

As any journalist or diplomat who has spent time in Guatemala will attest, no group there is more difficult to penetrate than the Guatemalan Armed Forces. As much a caste as an institution, the…

Researching Latin America

The instant outpouring of Web information on the Pinochet case got me to thinking about communications on my first trip to Chile during the Allende presidency. I was armed for Ph.D…