Gender and Education

Some Questions on Machismo, Pedagogy, and Values

A Mexican child concentrates on her homework.

“There aren’t very many young women [in Latin America] who can consider autonomous life plans.” — Gloria Corvalán, 1990

In terms of sheer numbers, girls in Latin American schools aren’t in such bad shape compared to other areas of the world. They have gained what is termed “gender parity”-girls are as likely as boys to enter first grade, are as likely (or unlikely) to finish primary school, and in some countries are even more likely to attend college. And yet despite this relative advantage, young women in Latin America continue to be restricted in the life plans they can consider for themselves.

When Cecilia, a Central American university student, went to see her professor about her grades, he made it clear that her grade would go up if she would offer certain services.

Marta, a teacher in a small town outside of Managua, found herself stuck without extra pay or childcare when she had to attend an intensive two-week workshop to learn about the Education Ministry’s new third grade curriculum. Cecilia’s and Marta’s personal dilemnas are typical of the daily choices affecting women in Latin America today. Gender continues to be a major issue in education.

Current research about gender and education focuses on educational quality. What does it mean to give a quality education to all children? What should a quality education look like for girls in Latin America? How does this differ from the education they are already receiving? What are the problems facing education for girls in Latin America? Where should gender awareness in education in Latin America be headed?

Economists tend to consider the question of access resolved when girls have equal access to schools, and so current programs focus on indigenous girls, the largest sector which still lacks access to basic education. Indigenous girls are less likely to speak the dominant language, less likely to go to school, less likely to complete basic schooling, and thus, less likely to be literate.

But access is only the first step in examining equality of education. After access, students must be guaranteed equality of survival rates-“staying power”-and then equal quality of education, and finally equality of post-school outcomes.

At a recent Harvard-sponsored conference on education in Central America, the absence of a space to discuss gender issues was noteworthy, as were the informal comments of various conference members. One representative from an international aid agency in Nicaragua said, “we know that there is no need to focus on girls’ education in Nicaragua because there are no problems there.” A participant from Costa Rica confided that feminists made her uncomfortable with their insistence on putting gender into every conversation. It appears that in formal education circles, gender is not considered a particularly relevant issue, except for programs to promote indigenous girls’ access to schools.

Why then, I find myself asking, do so many informal and adult education programs find themselves working with women, the female products of public education systems? Why are informal women’s programs focusing on literacy, small business administration skills, domestic violence prevention and gender awareness so widely funded? Perhaps if the critical issues affecting Central American women were directly addressed in the formal school setting, women would experience fewer severe crises as adults.

Researchers, analysts and Central American women themselves point to certain specific areas in which formal education could benefit from using a gender perspective in analysis.

- Women as teachers. Women make up the vast majority of primary school teachers in Central America. They receive salaries far below what almost everyone agrees would be an acceptable wage for a professional. They are expected to attend weekend and vacation in-service training sessions, and are expected to figure out childcare, transportation, and food. In the informal education sector, when developing women-centered professional development programs, women’s unique needs are addressed through alternative meeting hours and provision of childcare. What if teacher training organizers considered the unique situation of poorly-paid women teachers who are often also heads of households?

- Parental participation. Most “parent” meetings are dominated by mothers, who are often considered to be in charge of their children’s education. How is the mother’s experience in helping her child navigate the educational system helped or hindered by her gender? How does this experience end up being a changing experience for the mothers, as they also navigate the public space of the school?

- Harassment. Girls are physically and verbally harassed in the school or classroom. How much does this affect their willingness to participate in schools? How often are girls placed in compromising positions by male teachers at the secondary or university level?

- Values education. Where do values education and gender intersect? When values education extols the virtues of the nuclear family, in particular focusing on the role of woman as wife and mother, how does this impact a girls’ sense of herself and her future? How much does this contradict children’s daily experiences of far more varied family structures, and leave them confused about their position in society?

- Machismo. How does machismo play itself out in formal education? To what degree does education reinforce the machista values that degrade women? To what degree does it offer a way for girls to break out of roles?

- Pedagogy. Currently, gender theory is looking at the ways that different pedagogies are more effective for some children than others, and in particular at how girls tend to learn in comparison to boys. Does pedagogy in Central America favor boys? Do girls learn differently than boys? A person’s gender should not have an impact on which classes they are allowed to take, especially math and sciences, but their gender can and should have an impact on the pedagogy used to teach that person.

- What do girls say? How do they view the classroom and the school in their lives? What would they want to see change?

Jenny, one of those Central American girls, is one example. She repeated ninth grade three times, and finally stopped going to school altogether. “It won’t help me get a job anyway,” she commented. And in fact, studies indicate that for women who work in the sizable informal sector, their education has little positive effect on their economic future.

Other young women in Central America should not have to repeat Jenny’s negative experience. They should be able to dream of “autonomous life plans” for themselves, and not be restricted to the limited spaces currently offered them by society. While schools in Central America offer access to girls, they also perpetuate the social system that limits their opportunities. Central American schools-as well as many others in Latin America- face the challenge of addressing society-wide gender issues in the school setting.

Spring 1999

Caroline E. Parker is a first-year doctoral student in International Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. She has lived and worked in Nicaragua for 13 years.

Related Articles

Editor’s Notes: Booknotes

On March 10, 1999, President Clinton apologized to the people of Guatemala for the support provided by the U.S. government to that country’s repressive military-backed governments…

Society and Education

As a member of UNESCO’s International Commission on Education for the Twenty-First Century, I’ve come to realize that education is about much more than books. It’s about the “four pillars of…

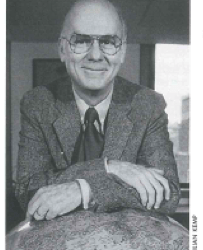

Noel McGinn’s Life of Learning

Noel McGinn, professor of education, had a normal American childhood in a small, sleepy town directly south of Miami-but 1200 miles south and across the Caribbean, in the Panama Canal Zone…