Getting from Here to There

Informality and accessibility challenges in Bogotá, Colombia

Passengers scramble for buses in Bogotá and climb aboard the speedy but crowded public transport system that traverses this sprawling city of seven million people, the capital of Colombia. Cyclists whiz by in designated lanes and taxis move from here to there in what seem to be endless traffic jams. The city has traditionally been divided between the poor southern part of the city and the more affluent north, but improvements in transport have slowly begun to break down those barriers. It’s not just about better infrastructure—along with infrastructure can come civic pride.

Neighborhood improvement through comprehensive public transport projects can make possible positive transformations. This is the case of TransMiCable, where residents take pride in their neighborhood and see improvements in safety and travel time: “Before, they used to say: ‘No, I’m not going to Ciudad Bolívar’ [a well-known district in the south], but now anyone wants to come to Ciudad Bolívar, even if it’s only to ride the TransMiCable. They will have another way of thinking when they come.” This reminds us that the human element must always be at the center of the urban mobility discussions and the main target of governments has to be to improve the welfare of citizens, especially the often-overlooked poor living on the literal margins. Such actions can make an enormous difference in the already challenging situation of those in a vulnerable situation.

A common sight across Bogotá is that of men and women working in the informal economy. Whether selling food on the streets or opening an unlicensed car repair shop across the city, millions of Bogotanos resort to informal activities to secure their livelihoods. It is precisely the needs of those workers that have to be taken into consideration when thinking about developing public transport from a perspective of inclusion and social justice.

From informal work to housing and transport, informality is present in all determinants of access to employment for many urban dwellers in rapidly growing cities in the Global South. According to the International Labour Organisation, 62% of all workers globally are in informal employment. In Colombia, estimates from 2019 suggest that this percentage was above 62.1% before the Covid-19 pandemic hit the region. Considering the scale of the informal sector, the role of transport in enabling access to employment needs to be questioned in terms of its ability to enable workers from all socioeconomic levels and forms of employment to reach their income sources and expand their potential to engage with the city’s economy.

The pandemic gave rise to some popular solutions such as pop-up infrastructure for cycling and other forms of sustainable transport. The pressing issue became how to develop alternative forms of connecting informal workers to the places where they work and, at the same time, to improve the built environment, using mechanisms that have been popularized in light of the pandemic.

Bogotá is doing lots of things right—but it still has a ways to go in meeting the basic needs of many of its citizens. It boasts some of the most iconic forms of public transport in the region, embodied by its Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system, Transmilenio, and a recently inaugurated aerial cable car, TransMiCable, connecting one of the poorest neighborhoods in the city with its BRT network. Despite being hailed as an iconic case of progressive urban transport policies in Latin America, Bogotá also grapples with significant rates of informal employment and a socioeconomic makeup that is unequal at its best and exclusionary at its worst. This leads to high transport expenditures for the poor, who spend long travel times to access employment from rapidly urbanizing peripheries, also marked by informal housing and transport. Such conditions make Bogotá an ideal case to illustrate the achievements, failures, and challenges associated with access to employment, serving as an example of larger dynamics commonly found across Latin American cities.

The segregated city, the concentration of employment and the peripheral poor

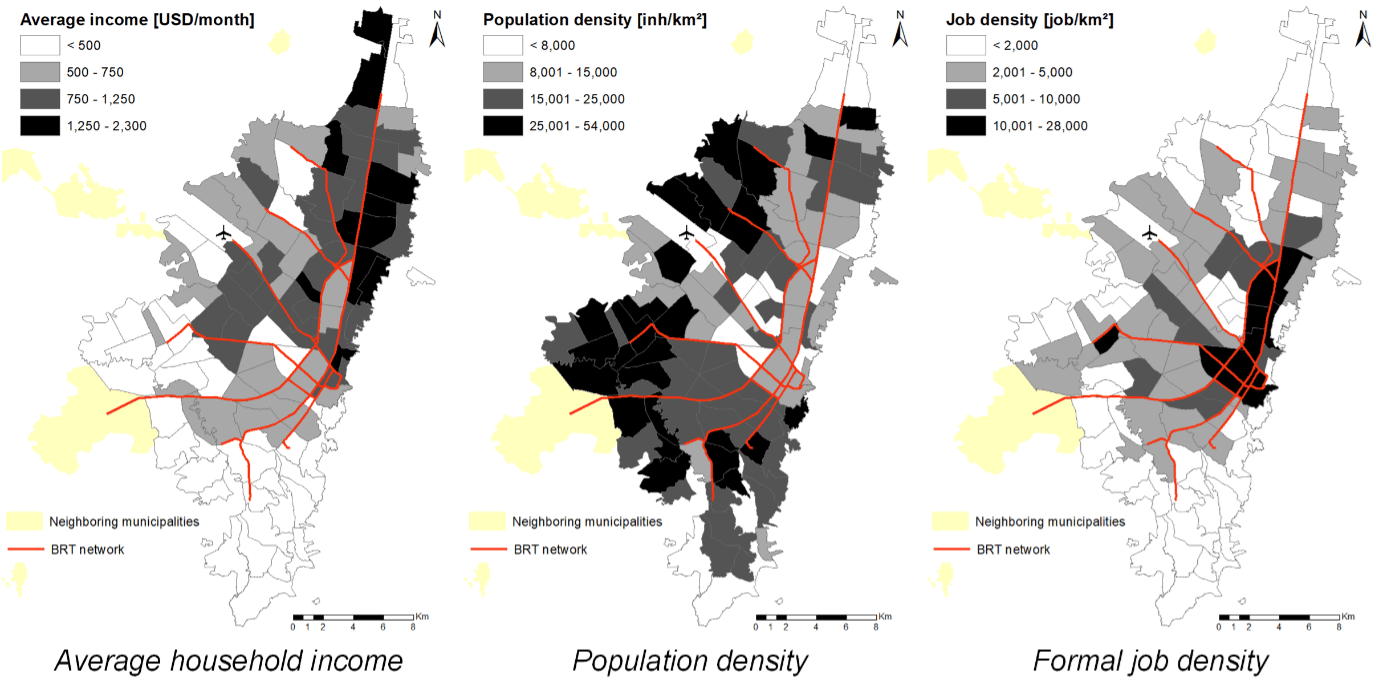

Large concentrations of economic activities in the eastern edge of the city are compounded by a land-use market that has driven up prices for decades in proximity to the main hubs of formal employment, becoming prohibitive for a majority of the population. Land occupation trends indicate a concentration of low-income settlements in the south and southwest of the city, with the wealthiest areas located in the northeast (as seen in Figure 1). As available land within the city’s boundaries runs out and costs increase, urban trends suggest that most of the urban growth will occur outside the city (neighboring municipalities) where most of the inhabitants will be either low or middle-income.

Figure 1. Population and employment location / Figura 1. Localización de empleos y población

This situation has given rise to important differences in the population and employment location throughout the city (see Figure 1). The unsatisfactory demand for affordable housing has encouraged people to occupy mostly unplanned and informal urban settlements, mainly in the second half of the 20th century. As a consequence, many informal neighborhoods emerged on the city periphery with poor urban living conditions. The densest neighborhoods are in the low-income zones near the southern and western borders of the urban area, where they can reach densities of up to 140,000 inh/mile2, and the two most crowded are in consolidated zones that started out as informal communities. Meanwhile, tall buildings, high-level formal employment and fewer people per square mile are common in the city’s central locations.

Despite the construction of the Transmilenio system, the current spatial mismatch—where people can get to easily and where they need to be— makes travel times remain very high, particularly for the low-income population. Since the poorest households live mainly on urban fringes, away from the main employment centers, the effects of such a spatial mismatch widen the inequality gap because travel costs are high, consuming much of already low income.

What accessibility to (formal) employment tells us

City-planning, design and public transport services must go hand in hand. Unfortunately, uncontrolled population growth in the periphery without urban amenities, services, and transport, this does not happen. This means community residents suffer from inadequate transport and are not integrated into the life of the city. The point is that not all public transport is created equal, especially when it comes to serving poorer citizens. Transmilenio tried to reverse this situation, improving access for these communities, although great challenges remain. One of those is access to employment: Public transport accessibility analysis suggests larger benefits in and around the wealthiest areas.

The spatial distribution of opportunities and transport services increase accessibility by public transport for short trips, while longer trips may benefit more from the availability of Transmilenio. This means that job accessibility for the wealthiest group is between 11% and 31% higher than the city average, regardless of how people get from one place to another. Recent studies suggest a negative effect of the spatial distribution of opportunities and public transport on equity, mainly to the poorest residents. Some people suggest that the poor could get around by biking, but we’ve found that low-income citizens have to travel disproportionately farther compared to wealthier ones. This also means marked differences in job accessibility between the cycling population, where up to 90% of the analyzed users have access to 30% of the job opportunities. The fact that it is harder to get to jobs strongly correlates with high levels of inequality both for motorized modes and the bicycle as suggested by previous research in the same context.

The improvements in coverage resulting from the integration of public transport, cycling infrastructure and transport subsidies for the poorest are intermediate requirements for enabling low-income communities to access more and better opportunities for employment. However, the public transport system faces serious problems of overcrowding and affordability. Bogotá has gone a long way in providing public transport services throughout the city but there is still a long way (and expensive) to go. Currently, more lines of Transmilenio are under construction (other more are proposed), the first Metro line is also under construction, and the implementation of new cable cars is also expected. Of course, that will not be enough. We must also think about improving the infrastructure for pedestrians and cyclists (and their safety) and without a doubt, make the use of cars and motorcycles less attractive and expensive.

Differences between the formal and informal job market

Almost one out of every two laborers in Bogotá work informally (around 48%). And most of these informal jobs are also concentrated and located on the eastern edge of the city. Therefore, the effects of the current spatial configuration of the city and public transport networks on improving accessibility to quality job opportunities imply a higher dependency on informal jobs as productive exclusion.

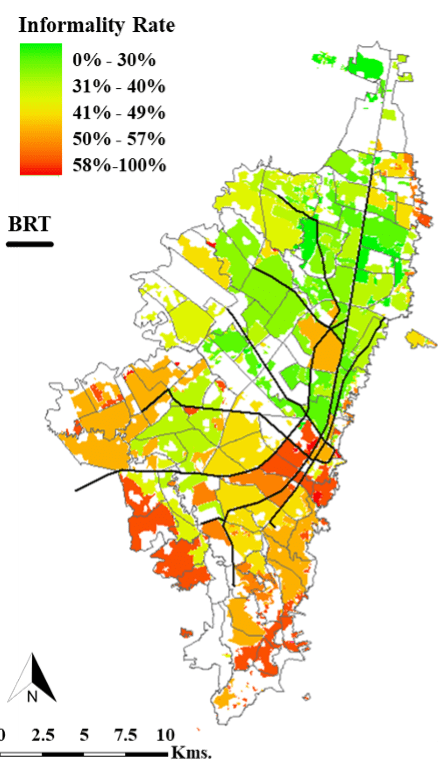

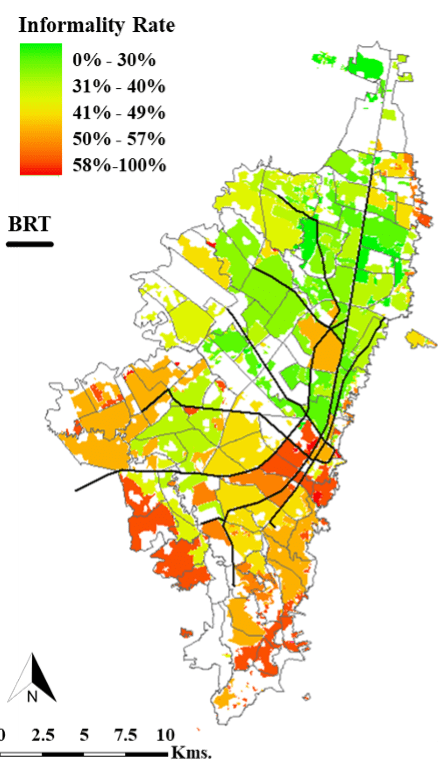

An analysis of travel destinations of workers living in zones with different informality rates shows how job locations vary, with more significant concentrations of informal workers testing how clusters of informal destinations are similar to those of formal workers. The informality rate in Figure 2 reflects the percentage of informal workers, understood as all workers who do not pay for their healthcare, are not registered in the pensions system, and do not have a written contract for their job. Such an analysis shows a high spatial correlation between poverty, low land values, densities, housing informality, and job informality. These conditions represent intersecting social disadvantages, which are reinforced by the fact that the city’s fringes have inadequate transport infrastructure. The informal worker lives in dense and low-income neighborhoods, many of which are of informal origin, adding a layer of complexity to structural processes of segregation and exclusion resulting from the way transport and urban development has taken place in Bogotá over the years.

Figure 2. Employment informality rate at the household / Figura 2. Tasas de empleo informal en origen

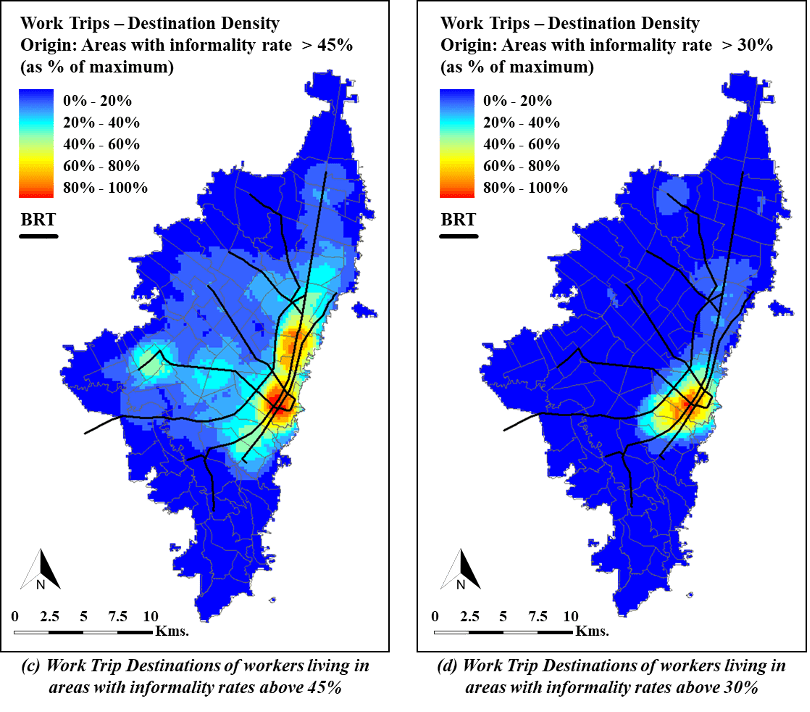

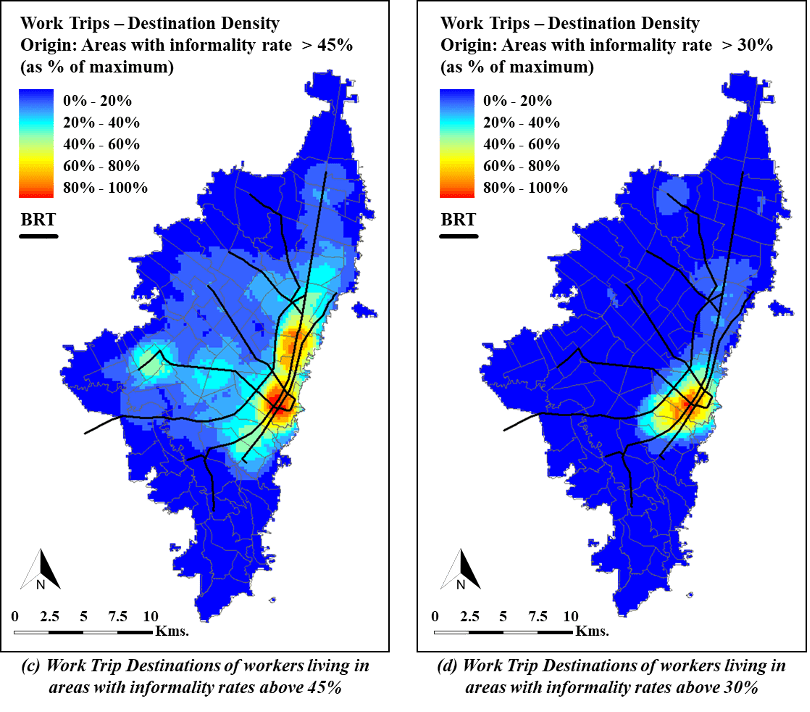

As shown in Figure 3 below, as the concentration of informal workers increases, destinations for informal jobs narrows down very quickly to hotspots. In the case of formal jobs, clusters of high demand coincide with the aggregated destinations on the eastern edge of the city. The opposite applies for high concentrations of informal workers, suggesting that commuters in areas where a majority of the residents work in the informal economy travel more frequently to a single, well-defined hotspot, near the older part of the eastern edge. Considering Bogotá’s segregated urban structure, highlighted results in Figure 3 suggest that citizens in the zones with a higher concentration of informality have higher travel costs and lower connectivity via high-capacity public transport. Such relationships have implications for transport supply and demand, as well as for the economic geography of Bogotá, contributing to understanding what the contribution of public transport and connectivity to informal job supply is. The fact that the main cluster of informal jobs is spatially closer to the ‘informal city’, as well as to the southern end of the city where more impoverished and less-connected neighborhoods concentrate, indicates a systematic bypassing of socially vulnerable populations in the process of transport planning and delivery.

Figure 3. Work-trip destinations by the concentration of formality/informality in the origin. / Figura 3. Destinos de empleo de acuerdo a la concentración formal/informal en origen

Looking forward, how to make it easier for the poor to access formal employment?

Economic segregation goes hand-in-hand with low mobility and accessibility. When all the low-income people live separated from everyone else and economic centers, fewer people make it up the economic ladder. In this context, we have to take a close look at the intersections between transport disadvantages with social disadvantages associated with precarious livelihoods and limited participation in the formal economy.

The case of Bogotá shows explicit relationships between the socio-spatial and productive distribution of the city and observable levels of exclusion. The uneven provision of public transport combined with a segregated distribution of housing has created and reinforced the dynamics of exclusion from the formal job market in the city. The distribution of hotspots of destinations of formal and informal workers suggests a quantitative and spatial imbalance in the availability of opportunities available for workers with different levels of inclusion in the formal economy.

Findings highlighted the scale of job informality and how it relates to other mechanisms of urban development such as informal housing (i.e., the informal worker tends to live in the “informal city”). Recognizing that nearly half of Bogotá’s population still has no access to non-precarious employment conditions (productive exclusion), puts into perspective the role of transport in increasing accessibility as a way to reduce social exclusion.

Little by little, Bogotá has increased its high capacity public transport, catering first to the formal demand and supply of employment, following traditional paradigms of transport planning and contributing to urban dynamics such as splintering urbanism. Although the current transport structure provides better coverage than before it was implemented, higher capacity still focuses on included and high and middle-income areas. Looking at the accessibility of informal workers has added value when considering the restrictions imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic and its current manifestation in Latin American cities. The narrow hotspot of destinations of informal workers maintains a unidirectional pattern for travel for people already in conditions of exclusion. Such populations have an explicit need to maintain livelihoods and income despite having limited or no access to healthcare and social security. Addressing such a challenge requires a better spatial understanding of the travel needs of those experiencing different levels of exclusion from the formal economy.

Moverse por la ciudad

Desafíos de la informalidad y accesibilidad en Bogotá, Colombia

Por Luis A. Guzman y Daniel Oviedo

En Bogotá, la capital de Colombia, una ciudad de más de siete millones de habitantes, la gente corre para subirse al bus y así usar el congestionado sistema de transporte público para sus travesías diarias. Paralelamente, los ciclistas pasan rápidamente por la extensa red de ciclorrutas y los taxis tratan de moverse de aquí para allá en lo que parecen ser interminables atascos de tráfico. Bogotá tradicionalmente ha sido divida en dos: la parte pobre en el sur de la ciudad y el norte más rico, aunque las mejoras en el transporte han empezado lentamente a derribar esas barreras. Pero no se trata solo de una mejor infraestructura: los proyectos integrales, bien implementados pueden mejorar la calidad de vida de las personas y así, mejorar el sentido de pertenencia por lo público, el orgullo cívico.

Las trasformaciones urbanas a través de proyectos integrales de transporte público pueden generar cambios positivos. Este es el caso de TransMiCable, donde los vecinos se enorgullecen de su barrio y ven mejoras en la seguridad y en los tiempos de viaje: Antes decían: “No, no voy a Ciudad Bolívar [una localidad muy conocida en el sur de la ciudad], pero ahora cualquiera quiere venir a Ciudad Bolívar, aunque sea solo para montar en el TransMiCable. Tendrán otra forma de pensar cuando vengan”. Esto nos recuerda que el elemento humano debe estar siempre en el centro de las discusiones sobre movilidad urbana y el objetivo principal de los gobiernos debe ser mejorar el bienestar de los ciudadanos, especialmente los más vulnerables. Estas acciones pueden marcar una enorme diferencia en la ya difícil situación de quienes se encuentran en una situación de pobreza y de exclusión.

En Bogotá, gran parte de sus ciudadanos trabajan en la economía informal. Ya sea vendiendo comida en las calles o abriendo un taller de reparación de automóviles sin licencia, miles de bogotanos recurren a actividades informales para asegurar su subsistencia. Son precisamente las necesidades de esos trabajadores las que hay que priorizar a la hora de pensar en planificar e implementar un transporte público desde una perspectiva de inclusión y justicia social.

Desde el trabajo hasta la vivienda y el transporte, la informalidad está presente en los determinantes del acceso al empleo para gran parte de los habitantes urbanos en el Sur Global. Según la Organización Internacional del Trabajo, el 62% de todos los trabajadores en el mundo tienen un empleo informal. En Colombia, las estimaciones de 2019 sugieren que este porcentaje estaba por encima del 62.1% antes de que la pandemia de Covid-19 azotara la región. Teniendo en cuenta el tamaño del sector informal, el rol del transporte para facilitar el acceso al empleo debe analizarse en términos de su capacidad para facilitar que los trabajadores de todos los niveles socioeconómicos y formas de empleo logren alcanzar fácilmente sus fuentes de ingresos y mejoren su potencial para participar en las oportunidades que ofrece la ciudad.

La pandemia generó oportunidades para implementar algunas medidas de movilidad sostenible, como nuevas infraestructuras para la bicicleta y otras formas de transporte sostenible. La cuestión urgente se centra ahora en cómo desarrollar formas alternativas de conectar a los trabajadores informales con los lugares donde se concentran los empleos y, al mismo tiempo, mejorar el entorno construido de la ciudad, utilizando mecanismos que se han mostrado viables debido a la actual coyuntura.

Bogotá está haciendo muchas cosas bien a pesar de la polarización política, pero aún le queda mucho camino por recorrer para satisfacer las necesidades básicas de muchos de sus ciudadanos. La ciudad cuenta con algunas de las formas de transporte público más emblemáticas de la región, encarnadas por su sistema BRT (Bus Rapid Transit), TransMilenio y un teleférico recientemente inaugurado, TransMiCable, que conecta varios de los barrios más pobres de la ciudad con la red de transporte público. A pesar de ser aclamada como un caso icónico de políticas progresistas de transporte urbano en América Latina, Bogotá también enfrenta altas tasas de empleo informal y una composición socioeconómica que es desigual y excluyente. Esto conduce a altos gastos de transporte para los más pobres (en relación con su ingreso), que pasan largos tiempos viajando desde las periferias, también marcadas por la vivienda y el transporte informal, a los centros de empleo. Tales condiciones hacen de Bogotá un caso ideal para mostrar los logros, fracasos y desafíos asociados con el acceso al empleo, sirviendo como un ejemplo de las complejas dinámicas urbanas que se encuentran comúnmente en las ciudades latinoamericanas.

La ciudad segregada, la concentración del empleo y los pobres en la periferia

La gran concentración de actividades económicas en el borde oriental de Bogotá se ve agravada por un mercado del suelo que ha elevado los precios durante décadas en las proximidades de los principales centros de empleo formal, volviéndose prohibitivo para la mayoría de la población. Las tendencias de ocupación del suelo indican una concentración de asentamientos de bajos ingresos en el sur y suroeste de la ciudad, con las áreas más ricas ubicadas en el noreste (como se ve en la Figura 1). A medida que el suelo disponible dentro de los límites de la ciudad se agota y su precio aumenta, los datos sugieren que la mayor parte del crecimiento urbano ocurrirá fuera de la ciudad (municipios vecinos) donde la mayoría de los habitantes serán de ingresos bajos y medios.

Figure 1. Population and employment location / Figura 1. Localización de empleos y población

Esta situación ha dado lugar a importantes diferencias en la localización de la población y empleo en toda la ciudad (ver Figura 1). La demanda insatisfecha de viviendas asequibles alentó a las personas a ocupar asentamientos urbanos en su mayoría informales y no planificados, principalmente en la segunda mitad del siglo XX. Como consecuencia, surgieron muchos barrios informales en la periferia de la ciudad con malas condiciones de vida y calidad urbana. Estas son las zonas más densas de la ciudad, de bajos ingresos y se ubican en los bordes sur y occidental del área urbana, donde se pueden alcanzar densidades de hasta 140,000 hab/milla2. Mientras tanto, los grandes edificios, el empleo formal de alto nivel y menos personas unidad de área son comunes en las zonas centrales de la ciudad.

A pesar de la construcción del sistema TransMilenio, el actual desajuste espacial —donde la gente puede llegar fácilmente vs. donde necesita estar— hace que los tiempos de viaje sigan siendo muy altos, especialmente para la población de menores ingresos. Dado que los hogares más pobres viven principalmente en zonas periféricas, lejos de los principales centros de empleo, los efectos de este desajuste espacial amplían la brecha de desigualdad porque el costo de viaje es alto y consumen gran parte de los ingresos, que ya son bajos.

Lo que nos dice la accesibilidad al empleo (formal)

La planificación, el diseño urbano y el transporte público deben ir de la mano. Desafortunadamente, con el crecimiento urbano descontrolado en la periferia sin equipamientos, servicios y transporte, esto no sucede. Esto implica que los residentes de esas zonas no cuentan con una cobertura adecuada de transporte y no están totalmente integrados en la vida de la ciudad. Además, no todos los transportes públicos son iguales, especialmente cuando se trata de atender a los ciudadanos de menores recursos en zonas de difícil accesso. TransMilenio intentó revertir esta situación, mejorando el acceso para estas comunidades, aunque persisten grandes desafíos. Uno de ellos es el acceso al empleo: análisis de accesibilidad del transporte público sugieren mayores beneficios en y alrededor de las áreas de mayores ingresos.

La distribución espacial de oportunidades y los servicios de transporte influyen en la accesibilidad para viajes cortos, mientras que los viajes más largos pueden beneficiarse de TransMilenio. La accesibilidad al trabajo para el grupo más rico es entre un 11% y un 31% mayor que el promedio de la ciudad, independientemente de del modo de transporte escogido. Estudios recientes sugieren un efecto negativo de la distribución espacial de oportunidades y el transporte público sobre la equidad, principalmente para los residentes más pobres. Se ha sugerido que estas personas pueden moverse en bicicleta, pero hemos descubierto que los ciudadanos de bajos ingresos tienen que viajar mucho más lejos en comparación con los más ricos. Esto también significa marcadas diferencias en la accesibilidad al trabajo entre la población ciclista, donde hasta el 90% de los usuarios analizados tienen acceso solo al 30% de las oportunidades laborales. El hecho de que sea más difícil llegar a un trabajo se correlaciona fuertemente con altos niveles de desigualdad tanto para los modos motorizados como para la bicicleta, como sugieren estudios previos en el mismo contexto.

Las mejoras en la cobertura del sistema de transporte público derivadas de su integración, de la infraestructura ciclista y de los subsidios al transporte para los más necesitados, son requisitos básicos para permitir que las comunidades de bajos ingresos accedan a más y mejores oportunidades de empleo. Sin embargo, el sistema de transporte público de la ciudad se enfrenta a problemas de congestión y asequibilidad. Bogotá ha hecho importantes avances en mejorar la prestación de servicios de transporte público en calidad y cantidad, pero aún queda un largo (y costoso) camino por recorrer. Actualmente, se encuentran en construcción más líneas de TransMilenio (se han propuesto otras más), la primera línea de Metro también está en construcción y también se espera la implementación de nuevos teleféricos. Por supuesto, eso no será suficiente. También hay que pensar en mejorar la infraestructura para peatones y ciclistas (y su seguridad) y sin duda, hacer que el uso de automóviles y motos sea menos atractivo y más caro.

Diferencias entre el mercado laboral formal e informal

Casi uno de cada dos empleados en Bogotá trabaja de manera informal (la informalidad en la ciudad es del 48%). Y la mayoría de estos trabajos informales también están concentrados en el borde oriental de la ciudad. Por tanto, los efectos de la actual configuración espacial de la ciudad y su red de transporte en las mejoras de la accesibilidad a empleos de calidad implican una mayor dependencia en el empleo informal, lo que conlleva exclusión productiva.

Un análisis de los destinos de viaje de trabajadores que viven en zonas con diferentes tasas de informalidad, muestra cómo varía la localización del empleo y cómo los destinos informales son similares a los de los trabajadores formales. Las tasas de informalidad en la Figura 2 reflejan el porcentaje de trabajadores informales, entendido como todos aquellos que no pagan por su seguridad social (salud o pensión) y no tienen un contrato laboral. Este análisis muestra una alta correlación espacial entre pobreza, precio del suelo bajo, altas densidades, informalidad habitacional e informalidad laboral. Estas condiciones representan desventajas sociales entrecruzadas, que se ven reforzadas por el hecho de que la periferia de la ciudad tienen una infraestructura de transporte insuficiente. El trabajador informal vive en barrios densos y de bajos ingresos, muchos de los cuales son de origen informal, lo que agrega una capa de complejidad a los procesos estructurales de segregación y exclusión. Este complejo fenómeno es resultado de la forma en que el transporte y el desarrollo urbano ha evolucionado en Bogotá a lo largo de los años.

Figure 2. Employment informality rate at the household / Figura 2. Tasas de empleo informal en origen

Como se muestra en la Figura 3, respecto al empleo formal, los destinos de alta demanda coinciden en el borde oriental de la ciudad. Por otro lado, a medida que aumenta la cantidad de trabajadores informales (en destino), las zonas que concentran dicha actividad se reducen. Esto sugiere que los destinos donde la mayoría trabaja en la economía informal, viajan con mayor frecuencia a zonas bien definidas, cerca del centro tradicional, también en el borde oriental. Considerando la estructura urbana segregada de Bogotá, los resultados de la Figura 3 sugieren que los ciudadanos de las zonas con mayor informalidad tienen mayores costos de viaje y menor conectividad a través de TransMilenio. Estas relaciones tienen implicaciones para la oferta y demanda de transporte, así como para la economía de Bogotá y contribuyen a comprender cuál es la contribución del transporte público a la oferta de empleo informal. El hecho de que la mayor concentración de empleo informal esté espacialmente más cerca de la ‘ciudad informal’, es decir, principalmente en la parte sur de la ciudad, donde se concentran los barrios de menores recursos y menos conectados, indica un desvío sistemático de las poblaciones socialmente vulnerables en el proceso de planificación y oferta de transporte de calidad.

Figure 3. Work-trip destinations by the concentration of formality/informality in the origin. / Figura 3. Destinos de empleo de acuerdo a la concentración formal/informal en origen

Pensando en el futuro, ¿cómo facilitar el acceso de los más necesitados al empleo formal?

La segregación económica va de la mano de la escasa movilidad y baja accesibilidad. Cuando la mayor parte de las personas de bajos ingresos viven separadas de todos los demás y de los grandes centros económicos, menos personas ascienden en la escala social. En este contexto, tenemos que observar de cerca las intersecciones entre las desventajas del transporte con las desventajas sociales asociadas a los medios de vida precarios y a la participación limitada en la economía formal.

El caso de Bogotá muestra relaciones explícitas entre la distribución socio espacial y productiva de la ciudad y los niveles de exclusión observados. La oferta desigual de transporte público combinada con una oferta segregada de la vivienda, ha creado y reforzado la dinámica de exclusión del mercado laboral formal en la ciudad. La localización del empleo de trabajadores formales e informales sugiere un desequilibrio cuantitativo y espacial en la disponibilidad de oportunidades para trabajadores con diferentes niveles de inclusión en la economía formal.

Los hallazgos también muestran diferentes escalas de informalidad laboral y su relación con otros mecanismos de desarrollo urbano como la vivienda informal (el trabajador informal tiende a vivir en la ‘ciudad informal’). Reconocer que casi la mitad de la población de Bogotá aún no tiene acceso a condiciones laborales no precarias (exclusión productiva), pone en perspectiva el papel del transporte en el aumento de la accesibilidad como forma de reducir la exclusión social.

Poco a poco, Bogotá ha ido aumentando su transporte público de alta capacidad, atendiendo primero a la demanda y oferta formal de empleo, siguiendo los paradigmas tradicionales de planificación del transporte y contribuyendo a dinámicas urbanas como el urbanismo fragmentado. Si bien la estructura de transporte actual brinda una mejor cobertura que antes, la mayor capacidad aún se enfoca en áreas tradicionales, de origen formal y de ingresos altos y medios. Estudiar la accesibilidad de los trabajadores informales tiene un valor agregado al considerar las restricciones impuestas por la pandemia Covid-19 y sus repercusiones en las ciudades latinoamericanas. La alta concentración de destinos de empleo informal mantiene patrones unidireccionales de viaje para personas que ya se encuentran en condiciones de exclusión. Estas poblaciones tienen una necesidad explícita de mantener sus medios de vida y sus ingresos a pesar de tener un acceso limitado a la seguridad social. Abordar este desafío requiere una mejor comprensión espacial de las necesidades de viaje de quienes experimentan diferentes niveles de exclusión de la economía formal.

Fall 2021, Volume XXI, Number 1

Luis A. Guzman is an Associate Professor at the School of Engineering at Universidad de los Andes (Bogotá, Colombia). His research interests include urban mobility, transport and land-use interaction and social, economic and spatial analysis of inequalities related to urban transport and policy evaluation in Latin America. He is also a consultant and adviser in different urban transport projects in Colombia and author of several articles published in international journals related to the evaluation of transport policies, poverty, equity and urban structure.

Daniel Oviedo is Assistant Professor at the Bartlett Development Planning Unit of University College London. An engineer and development planner by training, Daniel has over 10 years of experience in the analysis of social and spatial inequalities of urban mobility, and the role of formal and informal transport on social inclusion and well-being in cities of Latin America and Africa.

Luis A. Guzman es Profesor Asociado de la Facultad de Ingeniería de la Universidad de los Andes (Bogotá, Colombia). Guzmán está interesado en la movilidad urbana, el transporte y su interacción con los usos del suelo y el análisis social, económico y espacial de las desigualdades relacionadas con el transporte urbano y la evaluación de políticas en América Latina. También es consultor y asesor en diferentes proyectos de transporte urbano en Colombia. Autor de varios artículos publicados en revistas internacionales relacionados con la evaluación de políticas de transporte, pobreza, equidad y estructura urbana.

Daniel Oviedo es Profesor Asistente en la Bartlett Development Planning Unit del University College London. Ingeniero de formación, El tiene más de 10 años de experiencia en el análisis de las desigualdades sociales y espaciales de la movilidad urbana y el papel del transporte formal e informal en la inclusión social y el bienestar en ciudades de América Latina y África.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Transportation

Bridges. Highways. Tunnels. Buses. Trains. Subways. Transmilenio. Transcable. When I first started working on this issue of ReVista on Transportation (Volume XXI, No. I), I imagined transportation as infrastructure.

Modernity in Black and White

For years, one of my favorite pieces in the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA) was the iconic Abaporu (1928), by Brazilian artist Tarsila do Amaral: a canvas…

Transportation Itself Does Not Build Urban Structures

English + Español

Fina Rojas lives in the 19 de Abril at Petare, the densest and one of the largest self-produced neighborhoods in Latin America. Most researchers and policymakers define self-produced neighborhoods as “informal settlements.” However, these settlements occur from…