Health Under Siege

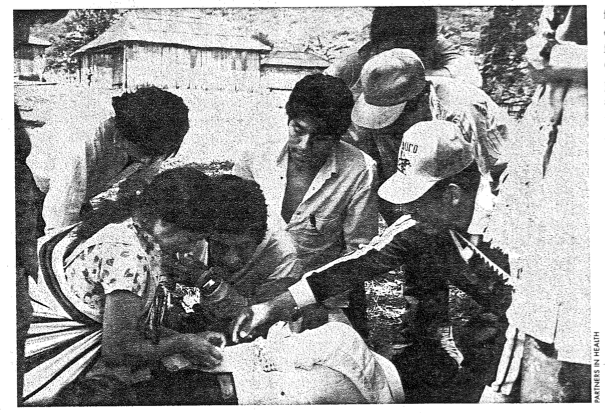

Community members work on a health project in Chiapas.

“The question is always simply this,” Partners in Health’s Dr. Kenneth Fox, declared at the opening of the “Health Under Siege: Community-based Responses to Structural Violence” symposium, “How can the best of what scholarship offers be used to improve health outcomes among the poor? The work we will hear about today embodies that mission. Whether you face the problem of AIDS among the poor of Cange or Roxbury; the epidemic of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Carabayllo, Peru; the wounds of exclusion and oppression in Chiapas or Cambridge or Egleston Square; wherever structural violence threatens to inmiserate, sicken, and crush the lives of the poor, you remain committed to thoughtful action. “

Community health workers from Mexico, Haiti, Peru, and the United States exchanged experiences with each other and with students, faculty, and interested community during the two-day symposium in October at Harvard. The program was co-sponsored by Partners in Health and its Institute for Health and Social Justice , Harvard Medical School’s Program on Infectious Disease and Social Change, and the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies.

The words of the community health workers, eloquent testimonies to their local conditions, reflected the mission of Partners in Health and its Institute, to examine the influence of inequalities on health and illness by linking scholarship with community-based experience. The organization takes on health issues, including “women, poverty, and AIDS; world orders old and new; tuberculosis; the political economy of the pharmaceutical industry; or the geography of violence and terror in Americas urban centers,” according to Fox, a pediatrician who is both an instructor at Harvard Medical School and this year’s Fellow at the Institute.

Partners In Health, under the direction of Paul Farmer and Jim Yong Kim, is a Harvard-linked program committed to improving health in poor communities. Its goal is to make a “preferential option for the poor in health care” by working with community-based organizations in “pragmatic solidarity.” Towards this aim, PIH offers technical and financial assistance, obtains funding and medical supplies, and helps administer its partner projects.

Most of the work has been done in close association with sister organizations in Haiti, Peru, Mexico, and the United States, particularly in the Roxbury section of Boston.

Although founded in 1987, the roots of the organization go back to 1983 when work began in central Haiti with a collective that is now called “Zanmi Lasante”–creole for “partners in health.” In 1956, Haiti’s largest river was dammed as part of an international development project, flooding the village of Cange and leaving its residents homeless. For years, Cange consisted of a few shanties and a dispirited core of “water refugees,” who had been forced to move to less fertile land. Gradually, Zanmi Lasante and the people of Cange built a large school and completed a project to bring clean water to the dusty settlement. Cange began to resemble a real village. Partners in Health grew out of this work and determination.

Blanca Jiménez, a Guatemalan from the Mam indigenous group, told the spellbound audience how she had resided as a refugee in Chiapas, Mexico, since 1990, working as a community health promoter, for the “Equipo de Apoyo en Salud y Educacion Communitaria.” Her husband Armando was “disappeared” early in the project, and she continued her efforts to find him while trying to work directly in bettering the plight of refugees. Armando had been the first and principle contact to Partners in Health, which in 1990 sought to bring his case to the attention of humans rights and government organizations. It was eventually determined that Armando had been abducted from a town on the Guatemalan border.

“Human rights groups believe that Armando was abducted by Guatemalan security forces,” declared Partner’s Paul Farmer. “All these people were doing was struggling for the right to health care and decent living conditions. We knew, from that moment on, that we would continue working with the people of Chiapas, including Guatemalan refugees like Blanca.”

Jiménez told the other community workers that she was especially interested in addressing women’s issues. “Discrimination makes women more vulnerable to poor health and disease,” she said. “We attempt to work with women as health promoters to discuss their reproductive rights and options that are pretty varied, such as making the decision to have or not to have children.”

Each year the Institute honors a “front-line worker for social justice” with its Thomas J. White Prize. Blanca Jiménez was so honored the day after the symposium.

Dr. Gabriel GarcÃa, who also works in community health in Chiapas, declared, “In Chiapas, the response to people’s demands – demands for food, health, education, and work- has been met with helicopters of American fabrication, guns from Great Britain, military airplanes of Swiss fabrication, bullet-proof vests, and an impressive number of militaristic outlays. It was estimated at the beginning of this year that in Chiapas there was one soldier for every family. It would be a lot better if instead there was one doctor for every family. “

GarcÃa observed that it costs U.S. $1.50 daily to feed each soldier ; the money that is spent on food for the community per family is $0.30 per day.

Haiti’s Zanmi Lasante community health workers, Bossuet Sainvilus and Loune Viaud, explained the organization’s history, that many members had been forced into exile, and that Paul Farmer, who served as the clinic’s medical director had been barred from entering the country after the 1991 military coup. The clinic nevertheless managed to reopen as quickly as it could.

Bossuet Sainvilus recalled the effects of the construction of a massive dam on the lives of those who lost their land. It is with these “water refugees” that. Zanmi Lasante has worked for the past 15 years.

But the coup d’etat of 1991 was, Sainvilus recalled, the biggest blow of all. “Even the mechanics of getting the clinic opened posed major problems because if you were two or three people gathered together to talk then you had to be talking about Aristide and they would arrest you. Little by little we got the clinic open again and what sort of patients do we see: people with tuberculosis, people with malnutrition, and people who had been beaten and tortured by the military. During that time we received a lot of threats from the military, and one of them said, ‘That little white guy (Paul) who worked with you had better not set foot in Haiti ever again.'”

The community workers were spied upon and harassed. Things finally changed in Haiti, with the return of Aristide in 1994 to a certain degree in terms of democracy, but the struggle for justice and against institutional violence continues, he said.

Jaime Bayona, the director of Socios en Salud in Peru, told of institutional violence in another form: malnutrition, forced sterilization, and inappropriately treated drug-resistant tuberculosis. But he reported that the team’s major effort to treat those suffering with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis was a success “likely to influence global policy, since this is not a disease that will simply go away.”

MarÃa Contreras, director of Soldiers in Health, brought the issue of Health under Siege home to her work in Roxbury: “I see such a similarity in the work that is happening in Chiapas Mexico, the work that we do here at Egleston Square. The land of plenty seems to be the land of nothing. The cry of hunger by so many families looking for food on Saturday evening or Sunday morning to the soldier office, make me understand what Gabriel (Garcia) said. Because this violence is silent no one cares. And it is this sort of violence that we are all fighting. “

Dr. Jim Kim, executive director of Partners in Health, concluded, “People who are on the front lines of fighting for health and social justice, should have an opportunity to sit in a room like this and discuss their experiences, and discuss ways in which more interaction and the sharing of ideas could help us all. And we are quite sure it will inspire all the rest of us to continue in our efforts in whatever way we can.”

Winter 1999

Related Articles

Linking Latin America

I have captured images of such seemingly disparate subjects as Mennonite immigrants to Mexico, Latina contestants for Selena standings, the Pope in Cuba, and traditional Sunday serenatas…

A Violence Called Democracy

As any journalist or diplomat who has spent time in Guatemala will attest, no group there is more difficult to penetrate than the Guatemalan Armed Forces. As much a caste as an institution, the…

Researching Latin America

The instant outpouring of Web information on the Pinochet case got me to thinking about communications on my first trip to Chile during the Allende presidency. I was armed for Ph.D…