In the Shadows of the Extractive Industry

A Hard Road for Indigenous Women

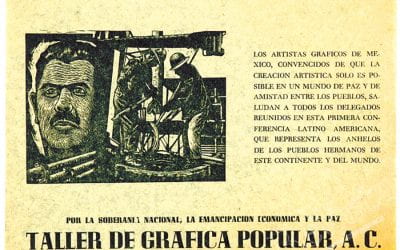

Leslie Searles makes a portrait of a woman preparing yuca, the traditional staple dish. Photo by Leslie Searles.

A telltale detail gave away the changing way of life for the indigenous Machiguenga women living around Peru’s most important gas project in the Cuzco Amazons: they had stopped harvesting yuca. Why bother planting the traditional tuber that was the mainstay of their daily diet if they could simply buy it at one of the dozens of little shops that had sprung up around the Camisea gas project installations? Indeed, why bother with yuca when one could easily buy rice? “If yuca is needed, you just buy it,” Eulalia Andrés Incacuna, an indigenous woman from the Kirigueti community, told us in 2006, when we first went to the far-flung villages two years before the gas project actually began full operations.

This change in food habits reflected new forms of economic exchange accompanying the Peruvian gas project operated by the private company Pluspetrol. Nine years later, health clinics in the zone report a statistical increase in chronic cases of malnutrition and sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV infection; alcohol consumption is also on the rise and often translates into domestic violence. In spite of the millions of dollars in royalties paid to the Peruvian state, the quality of life of the indigenous population—and especially that of women and children—has not improved.

Observing the effect of the extractive industries on indigenous women in the Amazons, Peru’s Vice Minister of Interculturality, Patricia Balbuena, asserts that “it is harder for women [than for men] to adjust to the changing forms of production that the extractive industry has brought to the Amazon regions, and this ultimately influences gender relations. The firms hire men who then acquire goods that displace women from their traditional routines,” observed the vice-minister, a lawyer with expertise in gender, development and demography.

Men no longer hunt nor fish nor dedicate themselves to agriculture. The economy of the family is greatly altered. It goes from being a money-free economy to a highly monetized one with all the social impacts that one can imagine. In her investigation, “Ideas about Progress in Indigenous Wage Workers: The Case of the Machiguengas and the Camisea Gas Project,” sociologist Cynthia del Castillo warns that communal indigenous life has been completely altered by alcohol use. “Tensions surround the adoption of new practices and attitudes with the introduction of a monetized currency, as revealed in extensive interviews. We are referring to excessive beer consumption. The fact that not all the persons interviewed were willing to talk about the subject made the tension visible and, paradoxically, underlined the conscious secrecy surrounding this subject,” she observes.

HYDROCARBONS, WOMEN AND TERRITORY

What happens in the Cuzco jungles is repeated with different nuances throughout the Amazon regions of South America. In the last fifteen years, increasing international demand for hydrocarbons has stimulated new explorations and exploitation of gas and oil in territories inhabited by approximately two million indigenous people, about half of them women. In these regions of Peru, Colombia, Brazil and Ecuador, there are at present 81 hydrocarbon fields under production and another potential 246 sites. Together, the area encompasses 0.41 million square miles or 15% of the entire Amazon region.

Peru has one of the greatest Amazon areas with leases given to the extractive industry; an estimated 80% of hydrocarbon concessions are located in titled indigenous lands, generating social conflicts with the local population. In some regions affected by the contamination of years of oil extraction, such as Loreto, indigenous women have organized and brought their complaints and demands to United Nations officials. “They have asserted that the contamination affects women in particular because of the changes brought about by the quality and availability of water, the effects on cattle raising (the only source of work for many women) and the negative effects on family health,” indicated a 2013 report by the former UN Special Rapporteur for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, James Anaya.

The social impacts of the extractive industries are complex, but seldom studied. “The extractive industry modifies gender relationships. They pay the workers well, but women have very little say in the use of this money,” Balbuena explains. Excluded from decision making, the indigenous woman becomes a passive subject of the impact of the extractive industries and the resulting social change.

The extractive industries affect indigenous women in many ways. “Water pollution is one of the main concerns of the indigenous women. With the loss of quality of this resource, the ability to guarantee her family’s health is greatly diminished,” says anthropologist Óscar Espinosa, a professor at the Catholic University of Peru who recently investigated the impact of oil exploration on two communities in the Amazon region of Bajo Marañón.

In his initial findings, Espinosa has found several cases of stress and severe symptoms of anxiety in indigenous women. “We interviewed many indigenous women and observed that many suffer from these problems. Indeed, several women have experienced hair loss. There’s no adequate treatment available for these women,” he says. Women leaders from the zone also associate oil industry contamination with an increase in the number of cases of cancer and birth defects. Uncertainty and the lack of response to these health issues only increase their anxiety.

THE SILENT ADVANCE OF HIV

Communities that were once abandoned by the state and isolated from urban areas have now become more involved in commercial exchange and migration to the cities, particularly among the men. As a result, by 2005 the Amazonian indigenous communities were reported to experience the first cases of HIV infection. Although statistics are hard to come by, local sources indicate that cases of HIV are on the rise.

In the communities bordering the Camisea project, the first officially reported case of HIV infection was in 2010. That year, the local health network identified 11 cases in the native communities located around the gas project. Mario Tavera, adviser to the Vice Minister of Public Health of Peru, says that the increase in HIV cannot be attributed to the extractive industry alone. “There are additional factors such as migration and economic exchange that ought to be taken into account in environmental impact studies of all these projects,” he observed.

Carlos Torres Huarcaya, an epidemiologist in Camisea’s zone of influence, explains that the HIV cases are imported into the area by the men. “The young indigenous men have begun to go to centers of nighttime entertainment set up in other towns, attracted by the great concentrations of employees and workers since the beginning of the gas exploitation.”

Distance and poor infrastructure of the health posts make the efficient and timely diagnosis of HIV quite difficult. The head of the indigenous program of the People’s Defender (Defensoría del Pueblo), Daniel Sánchez, recognizes the weakness of the state: “The health system is not prepared to handle the cases of HIV in the indigenous populations of the Amazons. It ought to have a specific strategy that would take into consideration the use of interpreters, as well as a greater state presence.” Half of the diagnosed cases are pregnant women who find out they have HIV during routine prenatal checkups. Only four patients have received antiretroviral drugs.

ALCOHOLISM AND FAMILY VIOLENCE

Another social impact associated with the extractive industry is the increase in alcohol consumption. In the communities near the Camisea project, beer has replaced masato, the traditional drink made from fermented grains that is consumed by the indigenous peoples of the Cuzco jungle. Crates of beer pile up in the port and in the small shops, and improvised bodega-bars sell it throughout the day. The local health authorities point out that although they have no formal study of the illnesses associated with alcoholism, the consumption of beer is evident on a daily basis.

No local studies exist linking domestic violence and alcohol in the indigenous populations of the Amazon, but most of the women associate abuse with alcohol consumption. The Peruvian vice minister notes with concern the lack of anthropological studies on the effects of the extractive industry on indigenous women. “There is no real sense of the size of the impact, starting with the way that monetary economies disrupt traditional gender relations. The breakdown in their traditional system will create new patterns if these changes are not monitored, ”observes Balbuena.

What can be done, then? The vice minister believes that Environmental Impact Studies have to be modified to incorporate more information about social impact. “When we talk about monitoring extractive projects, we think about natural resources and the effects on the environment, but the social impact requires the same degree of study as the environmental one. At present there are no anthropologists or specialists working on these problems; there is no analysis of gender issues. It’s not enough just to say there is a certain number of women in each community and to offer them workshops in cooking and textiles,” the vice minister concludes.

What’s to be done then? Environmental impact studies should incorporate more research into social impact. “Monitoring of extractive projects focused on natural resources and pollution, but not on the social impact,” declares Espinosa.

Studies about the extractive industries’ impact on the lives of indigenous women are very scarce. Del Castillo stresses in her thesis that it is necessary to carry out “more in-depth study to observe how spouses appraise the ‘progress’ their husbands say they are experiencing. The view of the individual who has not left the community, who has stayed to take care of the home, who supports her husband in his work tasks, who does not have the same opportunities as her spouse, can be quite different from the ideals of life held by the Machiguenga man.”

Without these studies, the Peruvian state’s support of the affected communities becomes deficient, above all because there is growing evidence that indigenous women and their children are experiencing a more precarious situation than they had in their traditional system of life.

Las sombras de la industria extractiva y el difícil camino de la mujer indígena

por Nelly Luna Amancio

Leslie Searles retrata a una mujer preparando yuca, el alimento básico. Foto por Leslie Searles.

Un detalle fue el primer signo de los nuevos tiempos para las mujeres que viven alrededor del proyecto gasífero más importante del Perú, en la amazonía del Cusco: las indígenas machiguengas dejaron de cosechar el tubérculo más tradicional de su dieta familiar, las yucas. ¿Para qué iban a sembrarlas si ahora podían comprarlas o reemplazarlas por arroz en las decenas de tiendas que aparecieron con la instalación del proyecto Camisea? “Si falta yuca se compra”, decía Eulalia Andrés Incacuna, indígena de la comunidad de Kirigueti, el 2006, cuando por primera vez recorrímos las comunidades aledañas al proyecto dos años después de que iniciara las operaciones.

La modificación de la dieta alimenticia de las comunidades indígenas advertía el inicio de los cambios asociados a las nuevas formas de intercambio económico que trajo el proyecto gasífero en Perú, operado por Pluspetrol. Nueve años después, los indicadores que actualmente reportan los puestos de salud de la zona revelan nuevos y más crónicos impactos en mujeres y niños: la desnutrición y las enfermedades de transmisión sexual como el VIH se han incrementado, el consumo de alcohol va en aumento y se traduce en casos de violencia contra la mujer.

A pesar de las millonarias regalías entregadas al Estado Peruano, las estadísticas revelan que la calidad de vida de la población indígena, y en especial de las mujeres y niños, ha empeorado.

La industria extractiva en la Amazonía se ha incrementado en las últimas décadas, ¿cuál es su impacto en la vida de las mujeres indígenas? La viceministra de Interculturalidad del Perú, Patricia Balbuena, sostiene que para la mujer el asunto es aún más complicado porque “les está costando reacomodarse a las nuevas relaciones productivas que traen estas actividades, y esto, finalmente, influye en las relaciones de género”. Los hombres son contratados por las empresas y usan sus sueldos para adquirir bienes que desplazan a las mujeres de sus rutinas tradicionales”, dice la viceministra, abogada experta en temas de género, desarrollo y población.

Los hombres ya no cazan, ni pescan, ni se dedican a la agricultura. Se altera la economía familiar. Se pasa de una economía no monetaria a otra monetaria, con todos los impactos sociales que esto supone. En su investigación “Ideas de progreso en los trabajadores asalariados indígenas: el caso de los machiguengas y el Proyecto del Gas de Camisea”, la socióloga Cynthia del Castillo advierte un hecho que ha trastocado la vida comunal indígena: el consumo de alcohol. “Las tensiones que se observan a partir del testimonio de los entrevistados tienen que ver con la apropiación de nuevas prácticas y actitudes a partir del ingreso monetario. Nos referimos al consumo desmedido de cerveza. El hecho de que no todos los entrevistados se mostraran dispuestos a conversar sobre el tema, hizo visible la tensión y, paradójicamente, el consciente ocultamiento hacia el tema”.

HIDROCARBUROS Y TERRITORIO

Lo que ocurre en la selva del Cusco se repite, con matices, en otras regiones amazónicas de Sudamérica. La creciente demanda de hidrocarburos en el mundo impulsó en los últimos 15 años nuevas actividades de exploración y explotación de gas y petróleo en territorios de la Amazonía habitados por alrededor de dos millones de indígenas (la mitad de ellas mujeres). En estas regiones del Perú, Colombia, Bolivia, Brasil y Ecuador existen actualmente 81 lotes de hidrocaburos en explotación y otros 246 sobre los que hay interés para la extracción. Juntos ocupan 1,08 millones de kilómetros cuadrados: 15% de toda la Amazonía.

El Perú es uno de los países con mayor superficie de Amazonía lotizada para la industria extractiva: se estima que el 80% de las concesiones de hidrocarburos se encuentran superpuestas a tierras tituladas de comunidades indígenas, lo que ha generado conflictos sociales con la población local. En algunas regiones, como Loreto, afectadas por la contaminación de décadas de explotación petrolera, han sido las mujeres indígenas las que de manera organizada han explicado sus quejas y demandas a funcionarios de las Naciones Unidas. “Ellas han expresado que la contaminación les afecta en particular por los cambios ocasionados en la calidad y disponibilidad de agua y los efectos negativos sobre la salud de su familia”, señala el informe del 2014 del relator para pueblos indígenas, James Anaya.

Los impactos sociales que traen consigo la industria extractiva en las mujeres indígenas son complejos. “La contaminación del agua es una de las principales preocupaciones para la mujer indígena. Con la pérdida de la calidad del recurso ellas han visto reducida sus posibilidades de garantizar la salud a su familia”, dice el antropólogo de la Universidad Católica del Perú, Óscar Espinosa, que desde hace unos meses investiga el impacto de la explotación petrolera en dos comunidades de la región Amazónica del Bajo Marañón.

En sus primeras indagaciones, Espinoza ha encontrado varios casos de estrés y cuadros severos de angustia en las mujeres indígenas. “Las hemos entrevistado y hemos notado que muchas presentan estos problemas. A varias se les ha comenzado a caer incluso el cabello. No existe para ellas un tratamiento adecuado”, dice. Las mujeres dirigentes de las zonas impactadas asocian la contaminación petrolera al incremento de casos de cáncer y los nacimientos de niños con malformaciones. La incertidumbre y la falta de respuestas incrementa su angustia.

EL AVANCE SILENCIOSO DEL VIH

El ingreso de nuevas actividades económicas en las comunidades indígenas que durante años permanecieron abandonadas por el Estado y aisladas del contacto con áreas urbanas, aceleró el intercambio comercial y la migración de sus habitantes hacia las ciudades, sobre todo de los hombres. Como resultado de estos nuevos procesos, a mediados de la década del 2000 se reportaron los primeros casos importados de VIH en población indígena amazónica. Aunque es difícil conocer durante estos años el impacto cuantitativo a nivel regional (porque varios países no tienen las cifras desagregadas por pertenencia étnica), informes locales señalan que su prevalencia va en aumento.

En las comunidades aledañas al proyecto Camisea, el primer caso de VIH reportado oficialmente data del 2010 y este año, la red de salud local, detalla que existen 11 casos en las comunidades nativas ubicadas dentro del área de influencia del proyecto gasífero. Mario Tavera, asesor del viceministerio de Salud Pública del Perú, opina que no se puede atribuir el incremento del VIH solo la industria extractiva, “hay una serie de factores adicionales, como la migración y el intercambio económico que deberían ser tomados en cuenta en los estudios de impacto de todos los proyectos”.

Sin embargo, Carlos Torres Huarcaya, epidemiólogo de la zona de influencia de Camisea, explica que los casos son importados por “los jóvenes indígenas que han empezado a frecuentar centros de diversión nocturna instalados en otros poblados, atraídos por las grandes concentraciones de empleados y obreros desde el inicio de la explotación gasífera”.

Las distancias geográficas y las malas condiciones de infraestructura de los puestos de salud dificultan un eficiente y oportuno diagnóstico. El jefe del programa indígena de la Defensoría del Pueblo, Daniel Sánchez, reconoce las debilidades del Estado: “El sistema de salud no está preparado para atender los casos de VIH en las poblaciones indígenas de la Amazonía. Se debería tener una estrategia específica, que considere intérpretes y una mayor presencia del Estado”. La mitad de los casos diagnosticados corresponden a mujeres gestantes cuyos resultados se conocieron luego del control prenatal. Solo cuatro pacientes reciben actualmente el tratamiento antiretroviral.

ALCOHOLISMO Y VIOLENCIA FAMILIAR

Uno de los impactos sociales asociados a las nuevos industria extractiva es también el incremento del consumo de alcohol. En las comunidades próximas al Proyecto Camisea la cerveza reemplazó al masato, la bebida tradicional de los pueblos indígenas en la selva cusqueña. Las cajas de cerveza se amontonan en el puerto fluvial y en las tiendas. Las improvisadas bodegas-cantinas las venden a cualquier hora del día. La red de salud local señala que aunque no se ha hecho seguimiento a las enfermedades asociados al alcoholismo, el consumo de cerveza es evidente todos los días.

No existen estudios locales sobre violencia familiar y alcoholismo en poblaciones indígenas de la Amazonía, pero la mayoría de mujeres indígenas asocia el maltrato familiar al consumo de alcohol.

La viceministra peruana advierte con preocupación la ausencia de estudios antropológicos sobre el impacto de la industria extractiva en las mujeres indígenas. “No hay una dimensionamiento real acerca de este impacto a partir de la incorporación de economías monetarias en los sistemas tradicionales de género, y las rupturas que podrían generarse”, advierte Patricia Balbuena.

¿Qué hacer, entonces? Los Estudios de Impacto Ambiental (EIA) deberían incorporar mayor indicadores sobre los impactos sociales. “El monitoreo de los proyectos extractivos inciden en los recursos naturales y la contaminación, pero no en el impacto social”, sostiene Óscar Espinoza.

Son escasos los estudios sobre el impacto de la actividad extractiva en la mujer indígena. En la tesis de Cynthia del Castillo insiste en la necesidad de “un estudio más profundo para tomar nota de las apreciaciones de las cónyuges en cuanto al “progreso” que sus esposos dicen estar viviendo. La mirada desde el individuo que no sale de su comunidad, que se queda al cuidado del hogar, que apoya a su esposo en el negocio emprendido, que no tiene las mismas oportunidades que el cónyuge, puede variar en comparación a los ideales de vida del varón machiguenga”.

Sin estudios, el acompañamiento del Estado peruano con las comunidades impactadas se vuelve deficiente, sobre todo porque existen evidencias de que las mujeres y los niños están pasando a una situación más precaria a la que tenían en el sistema tradicional.

Fall 2015, Volume XV, Number 1

Nelly Luna Amancio is a journalist specializing in the coverage of conflicts, the environment and human rights. She is editor and founder of Ojo-Publico.com, a website dedicated to investigative journalism, data analysis and new digital narratives. Contact: nellyluna@ojo-publico.com

Nelly Luna Amancio, periodista especializada en la cobertura de conflictos, ambiente y derechos humanos. Es editora y fundadora de Ojo-Publico.com, portal dedicado al periodismo de investigación, análisis de datos y nuevas narrativas digitales. Contacto: nellyluna@jo-publico.com

Related Articles

Oil and Indigenous Communities

On a drizzly morning in late February, a boat full of silent Kukama men motored slowly into the flooded forest off the Marañón River in northern Peru. Cutting the…

Mexico’s Energy Reform

The small, white-washed classroom at the University in Minatitlán, Veracruz, was packed with a couple dozen people who, although neighbors, had never met…

Geothermal Energy in Central America

When we think about global technology leaders, Central America does not typically come to mind. But Central American countries have indeed been in the…