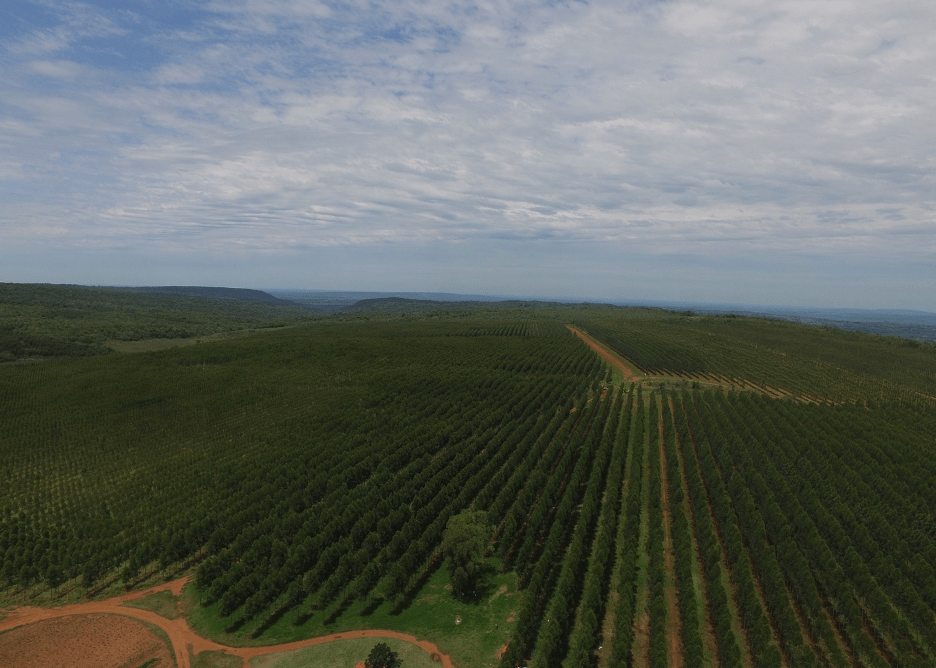

Innovating for Sustainable Development in Paraguay

A Model for the Amazons?

Forests. For many, they invoke beautiful images of trees and splendid scenes of nature, often inspiring deep reverence and respect for something so powerful and ancient. But as soon as one begins to peel back the branches, it is clear that this ecosystem and humans’ engagement with it is more complex than what originally meets the eye.

These swaths of land are home—not only for the flora and fauna, but also for people. For years, villages have relied on these forests for their livelihood, using wood for shelter, medicine and religious rituals. These natural resources are vital for both the local community and their survival. This is particularly the case for a small country nestled in the heart of South America, Paraguay, the self-proclaimed Land of the Guaraní.

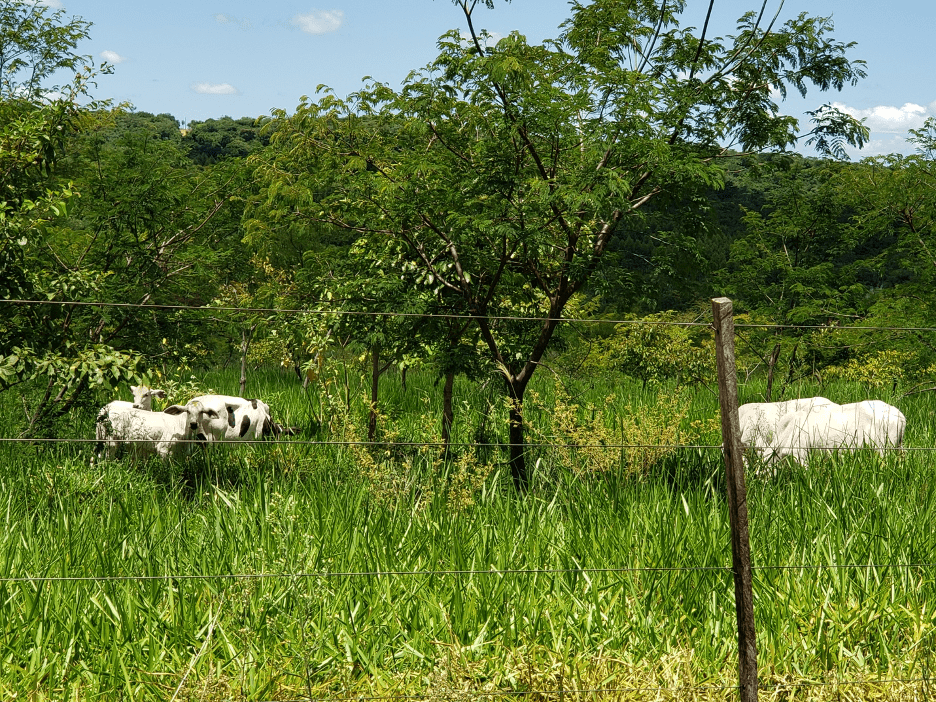

Native tree species can also combine with grass and cattle. Anadanthera colubrina (Kurupay) and Cordia trichotoma (Petereby) in a 3-year old plantation. Photo by Raul Gauto

The human-nature relationship often brings about a common predicament. How does one properly conserve land while ensuring that indigenous populations—such as those in the Amazon relying on these natural resources—continue to make a living? The choice cannot be as stark as total deforestation for the sake of economic development or an untouchable nature reservation for complete preservation. Instead, the answer must be somewhere in the middle, a more well-balanced approach of land stewardship that involves many stakeholders.

Unsurprisingly, the challenge of balancing these seemingly competing but vitally important demands has been an important topic for sustainable development.

Paraguay, home to just over seven million people—slightly less than the population of New York City—might have come up with a solution. Forestal Sylvis (FS), a Paraguayan social enterprise, has developed an innovative approach for forest cover recuperation and economic development that, if scaled, could have a tremendous impact on the Amazon and similar ecosystems around the world.

The founders, Raul Gauto and Eduardo Gustale, created FS in 2009 as a social enterprise providing an economic return for landowners and investors by planting forest on degraded areas or pasturelands and sustainably harvesting timber that can then be sold for profit. Gauto and Gustale sought to create a financially sustainable, private-sector solution with positive social and environmental impact.

As Gauto explains, his interest in conservation started with one of his first jobs working on government-based reforestation program that encouraged private companies to plant trees for tax-reduction credit. However, he was struck by the contradictory nature of the program—namely that the companies were paid to destroy natural forests in order to plant non-native pine trees. Inspired to learn more, Gauto went to the United States to study forest economics at Virginia Tech; it was there that his perspective shifted from reforestation to forest conservation. Afterwards, he spent years co-creating Fundación Moisés Bertoni—foundation dedicated to sustainable development in Paraguay—and supporting the organization’s large-scale programs with international organizations such as The Nature Conservancy. After years of on-the-ground experience, Gauto was awarded an Eisenhower Exchange Fellowship and spent several weeks in the United States. During this time, he traveled around the country, speaking with experts and seeing examples of forest conservation. He spoke with professors at Yale University, Cornell University, members of the World Resources Institute and even the Nobel-prize winner Murray Gell-Mann, who at the time was a board member of the MacArthur Foundation.

Silvopastoral system combining trees with grass. Tree rows are seven meters apart; there is then 2.2 meters between each tree. Photo by Dante Godziewski

These conversations planted the seed—literally—for FS. It soon became apparent to Gauto that it was not just about preserving forests but also about preserving and fortifying the livelihoods and lifestyles of those who inhabited these natural ecosystems. His observation, therefore, was that an integrated approach was needed to protect the rainforests and help locals.

One of Gauto’s most salient observations was the close link between poverty and forests. In his own words, “Poverty was the most important long-term threat to the existence of a nature reserve.” Part of this realization stemmed from his time at Fundación Moisés Bertoni, where he helped create and implement one of their flagship programs— a boarding school in the middle of a forest. Each year, the school offers free boarding education for 150 girls from ages 16 to18, from some of the poorest families in the region. During their three years at the school, girls learn both academic and entrepreneurial skills. The school seeks not only to educate women and help their families, but to also transform the social and economic politics of the region. By instilling in these young women an appreciation for forests and an awareness of their importance, the school has been able to spread this attitude more widely in the local community through the girls’ contact with families and neighbors.

Gauto explains that he then set out to create a triple-bottom-line company, or a company that measures success on three factors. Instead of just measuring financial return—as is common with most companies in the marketplace—this group also measures social and environmental impact and integrates all three components into their business model.

Given this triple-bottom-line approach, the company must focus on all three areas. Making sure all of these pieces work together is not easy and requires time. In 2010, the team rented their first piece of land using personal funds and began experimenting with the business model. The key was to talk with different stakeholders, better understand the local context, and identify existing incentive structures so that their company could identify how to effectively implement change.

Gauto outlines the three main components of the company’s theory of change:

- Economic:

Oftentimes, social enterprises struggle to find a sustainable business model. However, FS has created an attractive investment opportunity for many, boasting up to 14% internal rate of return (IRR). Organizations and individuals with capital can work with FS by specifying how much land they would like to invest in. FS then identifies land and searches for interested landowners with whom they can negotiate rent. These landowners continue to retain all property rights and simply rent a portion of their land to FS for a period of eight to ten years. During this time, the investor pays to plant, maintain and grow trees on lands that had previously been dedicated to agriculture (sugar cane and others) or cattle raising (grassland). These trees are combined with grass in between the rows, so that it can serve to feed cattle and increment the revenue. The combination of trees and cows not only generates an encouraging IRR, but it also dramatically reduces the negative impact of open-field agriculture. Local families, who now have a steady income, no longer have the need to continue clearing native forests for their sustainability. At the same time, because the eucalyptus trees used for reforestation are very efficient fuel, families satisfy their demand for fuelwood using the timber that is harvested every two years, as part of the field thinning process. This therefore reduces the desire to clear-cut the forest in order to obtain fuel.

FS explains that landowners then receive annual rent payment per hectare and a final percentage of the total revenue at the end of the multi-year rental. This set-up aligns interests and helps landholders see the value of making sure planted trees remain well-maintained. Investors will receive profits from the first tree-thinning at year three, a second thinning at year six, and the majority of their payment when the clear cut occurs at year eight or nine.

Gauto describes how FS itself receives a portion of the final profit at the end of year eight and also charges a tiered management fee to investors based on the number of hectares in which they have invested. Currently, the company has about 18 individual investors and hopes to make this investment opportunity more attractive by innovating in the financial market space.

FS is aware of the importance that secondary markets and liquidity play in the investment world. In global markets, stocks and bonds can be bought by one individual and then sold at any point in time. The purchase is not fixed—there is the possibility to sell these financial instruments if the investor wants a quicker return. Therefore, Gauto explains how FS is working with the government and the private sector to develop a similar secondary market. By creating a new financial instrument in Paraguay, people can sell on the open market, thereby increasing liquidity and hopefully the attractiveness of these investment mechanisms.

- Social:

As Gauto said he soon realized, working closely with all stakeholders—particularly the local population—is critical for the long-term success of their company and the protection of the plantations and the remaining rainforest. Similar to Fundación Moisés Bertoni’s school, which provided women with skills for making a livelihood, FS also provides families with the opportunity to make a sustainable living. To measure the improved wellbeing of families working in the plantation and in the region, FS has partnered with Fundacion Paraguaya to apply Poverty Stoplight to these families. This is a social tool which measures different dimensions of poverty so that families can identify their own areas of weaknesses and prioritize areas for improvement.

Previously, families cut down trees to plant sugarcane or grass, faster growing crops that promised more sizable profit, more quickly. Trees, on the other hand, took longer to grow, and it appeared that their main value-add was from immediately clear-cutting a region and selling the timber. However, FS’ payment structure has provided an economic incentive so that families switch from planting sugar cane to planting trees and stop cutting down existing forested lands. Paying a yearly rent smooths the income stream of the family, making it more consistent and reliable. At the same time, families are also incentivized to take care of the trees with the promise of final profit-sharing at the end of the eight years.

The combination of trees with grass completely covers the soil and avoids erosion from wind or rain. Photo by Raul Gauto

And while the company could easily use tractors and advanced technology to facilitate planting, FS says that they do not mechanize the process to the degree possible in order to employ more people. For every ten hectares (about 25 acres) of land under their stewardship, one family is given at least five years of continuous work. So far, they have rented over 4,000 acres from small-and large-landholders and created jobs for between 70 to 100 families, importantly also providing opportunities for women. The jobs required for taking care of trees varies, and women can perform several of the tasks themselves. Gauto explains how this provides them with their own income and independence, thereby strengthening their position in the family and community.

The founder also explains that the impact of FS has been so large that young people who originally left the region to find work elsewhere have moved back after hearing about the opportunities FS created in their villages.

- Environmental:

FS provides families with an income that dissuades them from deforesting the rainforest to plant crops such as sugarcane and grass. This work has been effective in extending the boundary of natural forests, as more trees are planted around these areas. One example is Parque Nacional Ybycuí, one of the most biodiverse parts of the country. Native animals now have more space, and certain species are beginning to return.

Gauto added that, over the years, he and his team have experimented to determine optimal tree spacing for the land. This is important, since trees require sufficient lateral space to properly express their genetic potential and produce high quality timber. At the same time, overcrowding requires additional effort, as trees must be thinned-out and cut back. Through trial-and-error, the team came up with a new land management methodology that cut costs by roughly 35%. The reduction in the number of seedlings, amount of fertilizer and effort to till the soil and prune the trees has significantly contributed to the price decrease.

At the same time, increasing the number of trees in the general region is vital for sequestering carbon, reducing erosion and protecting the watershed. Tree roots provide better water filtration and absorption in the ecosystem and improve water quality. Increased tree shelter also improves local microclimates and provides a healthier space for cows grazing between trees, since they are protected from extreme heat in the summer or frost in the winter.

This approach has attracted the attention of large organizations. In 2017, FS began partnerships with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) to plant native tree species in the same silvo pastoral system to recuperate degraded areas. Within the country, the government and society have also been taking notice. José Molinas, the former Minister of Planning, has stated that, “the sustainable development initiative proposed by Forestal Sylvis has a tremendous potential to reduce poverty, boost economic growth, and mitigate climate change. The initiative has a strong potential to reduce poverty by creating quality employment opportunities.” This recognition has largely stemmed from their holistic approach. Molinas describes their work saying that “by integrating quality wood production with efficient cattle raising, the initiative catalyzes technology adoption and sustainable investment to push both rural and urban economic activity. Tree growing allows for significant levels of CO2 sequestration, contributing to mitigate the effects of climate change.”

Thinning out of a 3-year-old plantation, producing over 30 cubic meters of fuelwood per hectare. Photo by Raul Gauto

To expand their work, Gauto explains that their next focus is to work with Paraguayan institutional investors and pension funds, which will hopefully be facilitated with the new secondary market.

Preserving forests is an important issue not only for Paraguay, but for other countries around the world. Protecting the Amazon and similar ecosystems is of utmost importance, but it is not easy to do so. Any potential solution must include the collaboration of many different stakeholders and be fundamentally cross-sectoral.

Despite this challenge, FS has come up with an innovative approach to not only protect these irreplaceable greenspaces but to also offer a social impact and be financially sustainable at the same time. Scaling this model globally could have a tremendous impact in sustainable development and lead the way for a new, more integrated approach for land conservation.

Spring/Summer 2020, Volume XIX, Number 3

Isabelle Foster was a Fulbright research scholar to Paraguay from Stanford University (until Fulbright recalled its scholars because of Covid-19). She graduated Stanford in 2018 with her BA and in 2019 with her MA. She is a researcher on economic development—particularly interested in innovation, entrepreneurship, and impact investing—and has done in-depth research on Paraguay over the past few years. During her time in Paraguay, she worked in the Presidential Delivery Unit with the National Innovation Strategy. In addition to her research, she is an avid rower and triathlete, is teaching herself guitar and has set her sights on visiting all the national parks in the United States. She can be reached at isabelle.foster@fulbrightmail.org or at her LinkedIn.

Related Articles

Amazon: Editor’s Letter

The Amazon is burning. The trees that have not been cut down are on fire. The crisis is now. When I began to work on this issue on the Amazon, that was pretty much my vision, and it was a real one. I was determined to make the magazine on the Amazon about…

How Democracies Die

How Democracies Die analyzes the main dangers that modern democracies face. As the authors warn, 21st-century democracies do not die in one fell swoop, in a violent way, by hands that do not always belong to the political system. On the contrary, modern democracies…

The Return of Collective Intelligence

My college Native American Culture professor, the Mescalero Apache scholar Inez Sánchez, told our class that we should regard the word “primitive” as synonymous with “complex.” I gained a better understanding of what Sánchez meant reading The Return of Collective…