Joiri Minaya’s Cloaking of the Statue of Christopher Columbus (2019)

Redressing and Cleansing

Fig.1 Statue of Christopher Columbus by Vittorio di Colbertaldo, shown vandalized at Bayfront Park in Miami on June 11, 2020 (Photo by Eva Marie Uzcategui Trinkl/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

Miami protesters sprayed trails of red paint on two monuments in Bayfront Park after the May 25,, 2020, murder of George Floyd. On the statue of Christopher Columbus, they scrawled (Fig. 1) “George Floyd” and “BLM,” as well as rudimentary Soviet hammer and sickle images (now sometimes representing a union of social classes), and stencilled raised fists, often viewed as an emblem of Black liberation and solidarity. The other statue, of Spanish conquistador Juan Ponce de León, was also inscribed with text, symbols and splattered red paint.

These protests, in support of racial justice and against racially motivated police violence, were part of a global wave of similar actions that physically altered and/or removed statues that commemorate polarizing figures associated with slavery and other forms of colonial enterprise, Confederate leaders and other examples of “troubling histories.” Scholars such as Renee Ater, Ana Lucia Araujo, Michele Bogart, David Olusoga, Kirk Savage, Shawn Sobers and James E. Young have explored the afterlives of monuments and memorials, and the issues involved in contemporary critiques of these structures.

Approximately six months before the Miami protests, in December 2019, a distinctly different form of intervention involving the statues had occurred. This time, however, the statues were modified as part of a series of public art installations by Dominican-American artist Joiri Minaya. Commissioned by Fringe Projects Miami, these works opened during Miami Art Week in early December, and were on view until January 18, 2020. In The Cloaking of the statue of Christopher Columbus behind the Bayfront Park Amphitheatre, Miami, Florida (Fig. 2) and The Cloaking of the statue of Ponce de Leon at the Torch of Friendship on Biscayne Blvd, Miami, Florida, the bronze sculptures were enrobed in a tight, light green, stretchy spandex that featured the artist’s meticulously-designed floral patterns. At first glance, the covered sculptures, with their light green hue, evoked the blue-green patina found on bronze sculptures that, over time, result from the oxidation process. Yet, upon closer inspection, the fabric’s decorative, “tropical” pattern becomes visible. Each design features stylized, meticulously-rendered illustrations of plants like rompe saraguey, an herb employed by indigenous populations and African descendants in the Americas for spiritual cleansing, protection and purification. Minaya’s incorporation of such plants, in referencing the survival of indigenous Taino and African diasporic ritual, belief systems and botanical prowess, may be viewed as a form of cleansing, or redressing, of the celebratory narratives surrounding Columbus.

The Cloaking series, as well as the June 2020 graffiti, are certainly two seemingly disparate approaches to the critique of monuments. Yet both represent critical moments in the afterlives of these sculptures that illustrate their contexts and shifting meanings over time. Although temporary, both kinds of interventions raise important questions about the ever-shifting role, meanings, validity and reception of monuments, and how they have come to be seen as obscuring or glossing over the “messy” or challenging details marking these histories.

Minaya’s project highlights the role that contemporary artists play in providing counter-narratives that question “official,” often tourist-driven monuments that tend to romanticize troubling histories. What is at stake in these dialogues? Quite simply, truth-telling in historical memory. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a monument may be defined as “a statue, building or other structure erected to commemorate a famous or notable person or event.” The word monument is derived from the Greek term mnemosynon and the Latin terms moneo and monere, meaning “to remind,” “to advise” or “to warn.” Hence the selection of the subject of a monument is about solidifying a particular memory, but also one that is wedded to the ideals and cultural, political and social mores of those in power in a particular time and place. Yet monuments are marked by an aura of permanence, a point often driven home by their medium (marble or bronze on a concrete base or pedestal, for example), their associated plaques (also often in bronze), their placement in areas of heightened public visibility, and their oft-monumental scale.

How do Minaya’s Cloakings complicate, question and/or interrogate heroicizing narratives of Columbus as hero-explorer? What is the significance of Minaya’s use of the term “cloaking” as well as the action of cloaking, a gesture that obscures or abstracts the image of Columbus, one that has long been romanticized despite the racism and genocidal practices associated with his story? Minaya’s counter-narrative subversively interrogates and “redresses” the Columbus narrative through pictorial and conceptual tactics in several ways. Her method of obscuring, blurring or abstracting his identity so that the sculpture “passes” as an aesthetically-compelling, Modernist public sculpture is one technique. Another is her use of the notion of the redressing or cleansing of a troubling historical narrative, epitomized by her “re-dressing” adornment of the statue as well as her use of a pattern design that includes plants such as the aforementioned rompe saraguey. In addition, her employment of deceptively decorative tropical patterns extends far beyond aesthetics in their evocation of resistance and cultural and spiritual retention despite colonialist practices.

Fig. 2 Joiri Minaya, The Cloaking of the statue of Christopher Columbus behind the Bayfront Park Amphitheatre, Miami, Florida, 2019, dye-sublimation print on spandex fabric and wood structure Commissioned by Fringe Projects Miami Photo by Zachary Balber. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Mining Art History

Minaya’s works deftly meld collage, performance art, photography, wallpaper and fabric design, murals, sculpture, film and video, and installation. They are often participatory, and thematically, they examine the politics involved in the display of Black and brown women as spectacle; the complexities of racial, ethnic and gender-based identity; interrogating notions of the tropical, whether in terms of identity and/or the decorative; and the performative use of women’s bodies as presumably-accessible exotic “offerings,” as part of the allure of tourism in tropical locales.

She has stated that her work is “grounded in performance,” and she often employs her own body in photographic series and video-based projects. In addition, her artistic practice reveals a highly astute, and frequently satirical, engagement with art history. In Portrait Request of 2011, Minaya handed index cards to passersby in New York City, asking them to write down “the things they quickly perceived or assumed about me.” It calls forth the examinations of mixed-race identity and other nuanced explorations of gender, race and class characterizing the 1970s and ‘80s works of pioneering Conceptual and performance artist and Kantian philosopher Adrian Piper. Minaya’s Container series evokes Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta and her performative references to Afro-Cuban Santeria, with conceptually rich themes involving the earth, womanhood and goddess-figure imagery that often incorporated her own body. Minaya’s Container #6 (Fig. 3) and other series images reference European modernists’ fixation on odalisques, the reclining, largely female and often nude figures that populated Orientalist, 19th–century French paintings. Yet Minaya’s odalisques transform the figure from one that is nude or semi-nude and that primarily functioned as an object of desire, to one that is adorned in form-fitting, colorful and explosively dynamic bodysuits, gazing slyly and provocatively at the viewer with a degree of bold intensity that somehow borders on aggression. These odalisques appear to let us know that their pose, their adornment, their presence here is, decidedly, a performance, and that this staging has little to do with everyday lives beneath the embellishments.

Fig. 3 Joiri Minaya, Container #6 at Juan Dolio Beach with audience #1, 2020 Archival inkjet print on Hahnemühle paper, Courtesy of the Artist

Count Vittorio di Colbertaldo’s Columbus

Italian sculptor Count Vittorio di Colbertaldo (1902-1979) was commissioned to produce the bronze monument to Columbus, dedicated on October 12, 1952 in Miami’s Bayfront Park. The Miami commission process was organized by the Italian consul in Miami, Dr. J.M. Gaetani, who created a Citizens Committee. The City of Miami contributed the placement site without monetary support, so the Committee began a successful fundraising mail campaign. Colbertaldo had been a member of Benito Mussolini’s bodyguards, part of an elite volunteer corps known as “The Black Musketeers” because of their all-black dress uniform.

Colbertaldo’s 27-foot high Columbus is a figure of immense physical power. His visage is tilted upward, and he has a broad, uplifted chest. He stands with legs spaced evenly and widely apart, and they are not in contrapposto. His hands, with open palms facing upward, are positioned at hip-level. The stiffness of his pose and his hand gesture resembles a form of kouros, an archaic Greek figure that holds stylistic affinities with earlier Egyptian sculptural forms. In considering its lack of contrapposto and prayer-like position of the hands, the Columbus figure may have more in common with saintly figures from Christian iconography as well as with, of course, classicizing fascist sculptures in Italy that emphasized athleticism.

This linkage with Christian symbolism gains even more strength when examining Colbertaldo’s other U.S.-based Columbus monument (Fig. 4), dedicated in San Francisco in 1957. The California Columbus has a cross prominently placed at the center of his chest; it hangs from a necklace. He is also crowned with a Christ-like mane of flowing hair that drapes gently below the back of his neck. He has a stocky, robust body supported by a set of thick, trunk-like legs. With his long, flowing cape behind him and solid, muscular build, the San Francisco Columbus appears to be a melding of Christ and DC Comics’s Superman, who first appeared in Action Comics #1 in 1938. Colbertaldo’s focus on a figure that is both saintly as well as physically fit was likely shaped by his Catholicism as well as fascist ideals.

The California Columbus has also been defaced on several occasions, including on Indigenous Peoples Day in 2019, when it was bathed in red paint with the following text: “Destroy all monuments of genocide and kill all colonizers.” The sculpture was removed in June 2020 to ensure public safety after a Portsmouth, Virginia, protest and statue removal resulted in grave injuries for one of the protesters. The figure of Columbus, celebrated by hundreds of monuments and memorials in the Americas, and countless others globally, has become a lightning rod for dialogues about how cities engage with colonial and other challenging histories, and whether such monuments should remain on view in light of their location in racially and ethnically diverse urban settings and changing societal values.

Fig. 4 Count Vittorio di Colbertaldo, Christopher Columbus, Telegraph Hill, San Francisco, CA, dedicated on October 12, 1957

Cloaking Columbus

In order to properly assess Minaya’s intervention, it is necessary to ask: How do monuments speak? To begin, we might ask: Where is the monument placed? How might we consider the meaning and function of Cloaking in relation to its Bayfront Park location? Bayfront Park, on Biscayne Bay, has been referred to as Miami’s “first public gathering space,” hosting athletic events, concerts, beach activities and other events. Also, how does scale come into play, and are we meant to gaze up at it, to behold it? If a representational/figurative portrait, what kind of gestures, poses, facial expressions and vestments may be discerned in the monument? Are they easily legible as part of an iconographic system of symbolic content? Is there text on or around the sculpture? If so, who produced it and when?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines decoration as “something used to adorn or embellish,” or a badge or medallion presented as a mark of honor. Other associated ideas suggest an aesthetically pleasing quality without a great deal of conceptual depth. In terms of visual culture, decoration has long been associated with the decorative arts, including ceramics, furniture, textiles and crafts—viewed as distinct from the fine arts such as painting and sculpture. This hierarchical comparison often centers on the idea of the decorative arts as useful or practical, visually pleasing, and lacking in conceptual complexity, ideas that are deftly countered by texts such as Glenn Adamson’s Thinking Through Craft (2019).

Minaya’s subversive strategies actively blurs these boundaries between high and low. Her use of fabric—synthetic spandex in particular—complicates the underlying monuments’ association with permanence. The fabric covering, here, like any other adornment, is temporary. In addition, it also blurs the fashioning of gendered identity and presentation in that Columbus is covered in a fabric that might be considered feminized in its floral effervescence. Minaya has previously explored the role of fabric and adornment in gendered norms in works like La Rompe Ojos (a common phrase used in the Dominican Republic that means to incite envy in others by dressing in overtly ostentatious adornment). She has stated that her mother has long operated a clothing store, and for La Rompe Ojos, she drew from the highly embellished women who frequented her mother’s shop.

Also critical to Minaya’s cloaking of Columbus is her use of the stretchy, expandable, somewhat revealing (and commonly-gendered) spandex, largely associated with athletic wear or vacation wear. In terms of male figures, spandex is linked (often with humorous undertones) with superheroes, Chippendales dancers and/or those involved in aerobic exercise in the 1980s. Arguably, spandex has not been commonly perceived as heteronormative male attire.

Minaya’s use of the term “cloaking” is also highly significant here. A cloak, according to the Oxford English dictionary (OED), is “a thing that hides or covers somebody/something.” In cloaking Columbus, she is also literally re-dressing the narratives surrounding him as an historical figure. According to the OED, to redress something is to “correct it, to right a wrong,” to fix something that is unfair or wrong, to “make a situation equal or fair again.” Minaya’s “cloaking,” or use of a patterned fabric results in a form of abstraction of the Columbus figure. The fabric simplifies and/or emphasizes the statue’s underlying sense of movement or gesture, while also obscuring the identity and message of the figure. If seen at a distance, it hides in plain sight as an aged bronze work of art. The covering also suggests a sculpture that is hidden away in museum storage, draped or wrapped in plastic or quilt-like material and therefore not seen/not speaking.

Minaya’s work is certainly marked by satirical play, employing elements of humor while also providing serious critique. To that end, the taut fabric of the Columbus figure also has the potential, when seen at various angles (Fig. 5), to make the figure’s gesture appear lewd, like a pointed middle finger, or, perhaps, a “pup tent” beneath clothing. He may also be read as a cartoonish, ghost-like presence, further undermining the physical power of the cloaked figure beneath the fabric.

The cloaking also recalls Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s wrapping of architectural structures, resulting in impressively grand installations that revealed new ways of aesthetically experiencing these structures. The artists’ transformation of the Reichstag, long presented as a symbol of German unity, culminated in a silvery structure comprised of tightly wrapped, slivered glass-like sharp folds, an imposing form that appeared ominous in its scale and state of containment. Minaya’s Columbus also appears restrained, and the tightness of the fabric implies undertones of aggression, violence or torture, despite its efflorescent, pale green fabric. The spandex functions as a form of binding or containment of the figure.

Through its dramatic yet ambiguous gesture and patterned fabric, the cloaking functions as a form of costume in conjunction with Columbus’s theatrical pose. And, in its use of subversion and a temporary reversal of hierarchies, it shares affinities with the notion of the carnivalesque as characterized by Russian linguist and literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin. To that end, might we also view the cloaking fabric as a form of full-body mask? Masks conjure, at turns and in varying degrees, an aura of secrecy, clandestine behavior, hidden agendas, deceit (whether insidious or playful), the theatre or the theatrical, the carnival and/or the masquerade and, above all, the performative. This idea of the performative fits snugly into Minaya’s investigations of constructed identities, particularly those involving performed exoticism within tourist-based economies.

Fig. 5 Joiri Minaya, The Cloaking of the statue of Christopher Columbus behind the Bayfront Park Amphitheatre, Miami, Florida, 2019, dye-sublimation print on spandex fabric and wood structure Commissioned by Fringe Projects Miami Photo by Zachary Balber. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Deceptively Decorative: “Plants of Resistance”

One might be tempted to compare Minaya’s patterns to the late 19th-century Arts and Crafts Movement works of British textile and wallpaper designer William Morris, an early socialist and champion of handmade production. Morris’ designs, informed by medieval European and Islamic precedents, utilized repetition and simplification of form, and highlighted the graceful lyricism of elegantly curved leaves, flowers and vines. Minaya’s patterns also mine the natural beauty of her chosen flora, and they are much more subtle and less compositionally crowded than many of Morris designs. In addition, they are distinguished by her conceptual use of the aforementioned “plants of resistance.” As she has noted in several interviews, her aesthetic is partly informed by 18th and 19th-century colonial, botanical catalogue illustrations. She began designing her own patterns in 2019 after asking herself, “Why am I appropriating patterns when I can design my own?” as she told me in a March 2021 interview.

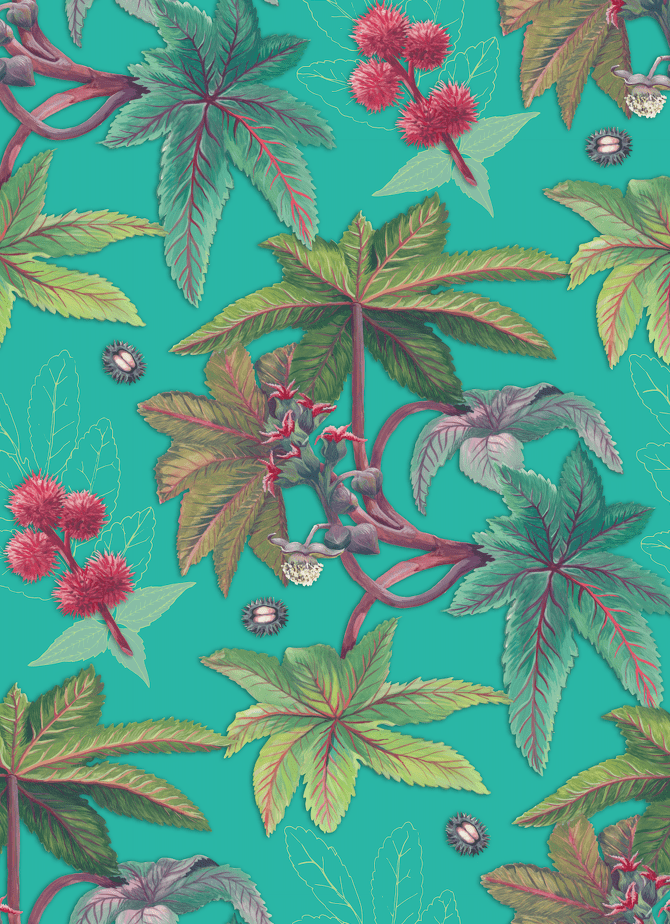

Minaya’s Cloaking (Columbus) pattern (Fig. 6) includes stylized castor bean plants, with their glossy, red, green and sometimes purple star-shaped leaves with serrated edges, and red, burr-like castor bean pods. These plants were brought to the Americas by enslaved Africans, who processed them for medicinal purposes and successfully distilled their non-toxic components after removing the toxin called ricin. Also present in the design is yaupon holly, used by several indigenous groups for purging, or cleansing rituals. Coontie leaves were also included, with roots that were used to make bread by indigenous populations. As noted earlier, rompe saraguey is also central to the pattern, and its compact, toothy leaves of have long been used in Yoruba-based belief systems for cleansing and depojos, or rituals involving the purging of bad luck or negative feelings or spirits.

The Ponce pattern design includes the tiny, apple-like fruit of the manchineel tree, known in Spanish as manzanilla de la muerte (little apple of death), sometimes referred to as the world’s most dangerous tree. The Calusa, Florida-based Native Americans that resisted colonization for more than 200 years used it to poison the arrow that eventually resulted in Ponce’s death. The inclusion of these particular plants represents the continuing survival of indigenous and African diaspora-based belief systems and ritual despite colonial oppression and genocide. As she has noted of her work, “I’ve been particularly drawn to species that relate to (hi)stories of resistance, plants that symbolize the resilience and hope of the Caribbean people in the face of hardship and adversities, flora that speaks of transformation and healing, highlighting stories of survival but also speaking of continuity, nurture, solace and spiritual strength.”

Fig. 6 Joiri Minaya, Fabric Pattern design for The Cloaking of the statue of Christopher Columbus behind the Bayfront Park Amphitheatre, Miami, Florida, 2019, dye-sublimation print on spandex fabric and wood structure Commissioned by Fringe Projects Miami Photo courtesy of the artist.

Minaya’s Cloaking…Columbus installation serves as a counter to the idealized, lionizing narratives that have long been associated with Columbus. Might we consider this work an inducement for us to actively re-assess the role and validity of monuments and their ever-shifting contexts, and to question the sanitized representation of historical figures? Might we also consider, and appreciate, how contemporary work like Minaya’s Cloaking provides us with new ways of articulating—conceptually and pictorially—the unspoken truths that lie beneath these traumatic yet embellished histories, truths that are often camouflaged there, “kept under wraps,” beneath the mask?

Spring/Summer 2021, Volume XX, Number 3

Mora J. Beauchamp-Byrd, Ph.D., is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Art and Design at The University of Tampa, where she teaches courses in Modern & Contemporary Art and in Museum Studies. An art historian, curator, and arts administrator, she specializes in the art of the African Diaspora; Modern and Contemporary art, including a focus on late 20th-century British art; Museum & Curatorial studies; and representations of race, class and gender in American comics. Since 2020, she has been a member of the Board of Directors of the College Art Association (CAA), where she currently serves as Vice President for Publications.

She would like to thank Joiri Minaya for her kind and gracious assistance. She also extends her sincere thanks and appreciation to Erica Moiah James and Marianne Eileen Wardle for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Related Articles

The Eye that Cries: Peru’s Unreconciled Memories

English + Español

In Lima, Peru, in the midst of Campo de Marte, a public park named after the god of war, a Zen space for reflection is guarded by a cast iron fence. El Ojo que Llora (“The Eye that Cries”…

Editor’s Letter: Monuments and Counter-Monuments

Cuba may be the only country on the planet that sports statues of John Lennon and Vladimir Lenin. Uruguay may be the first in planning a full-fledged monument to the victims of the Covid-19 pandemic.

A Monumental Battle for the Story of Texas

In 2016, I visited the Alamo, as part of my first real return to Texas in many years. I had mapped out a road trip with my brother Edmund Roberts. Though Edmund has long known of…