Latino Families and the Educational Dream

Resilience along a Rocky Road

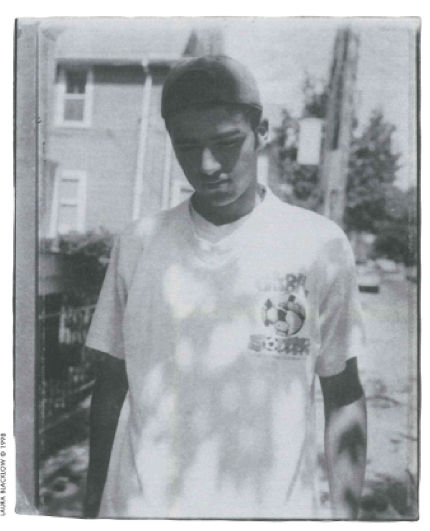

Portrait of David Paez in Central Square, Cambridge. “The road to American dreams is filed with potholes…and hope.”

Insisting that we do our interview in English, Ricardo Robles reluctantly recalls the dreams he had for his children when first arriving nine years ago to the U.S. from Zacatecas, Mexico. “They deported me three times, but I kept coming back. I thought here my kids could get the education you know to be successful. I wanted a job and to find a house…to learn English.” Fate had other ideas. His 17 year-old son Carlos, a member of the Lil? Aces street gang and a high school dropout, was killed in a drive-by shooting. His daughter Anita, now 15, wants nothing to do with gangs, but she is failing several classes in school. Alma, a fourth grader, is a star student and the family?s pride. Ricardo is worried about his children but still hopeful. Ricardo explains, “Life was very hard back home. But at least in Mexico, I had all my children. I always think of going back for good, but I have two more (children). I hope it is better for them. I watch them carefully.” For the Robles family, the road to the American dream has been full of potholes, but the real story lies in the family’s resilience and two immigrant’s struggle to meet the challenges of educating their children. New immigrants already make up a significant portion of the school-age population in the U.S. and Latinos will be the majority in such states as California and Texas by the year 2010.

Of course, mass immigration is nothing new to our country. Between 1890 and 1920, America invited Europe to “give us your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” After two generations, these immigrants assimilated quite easily into the American middleclass. But it seems we have not hung out the same welcome sign for our Latin American neighbors. Recent immigrants are poorer, have less education and fewer marketable skills that would enable them to take advantage of a burgeoning global economy which has become increasingly technological and more demanding of its worker’s abilities. Coupled with lingering stereotypes and few resources, it has been difficult for Latino immigrants to move into the mainstream. In no place has this been truer than in the public schools.

Education is the single best predictor of the future success of immigrant children, but the schools have hardly met the challenge of educating these youth over recent years. Latino immigrants have the worst academic performance and the grimmest economic prospects in young adulthood of any group. Their dropout rate remains more than double the rate of African-Americans and over 3.5 times that of Anglos. This rate has improved little over several decades and later generation Latino origin youth fair only slightly better. As a result, Latino youth continue to be more distanced from the public school system each year, an argument supported by disproportionate dropout statistics, student suspensions, expulsion and retention rates and low standardized test-scores.

Despite these dismal results, Latino families continue to have high aspirations for their children.

One study of 13 high schools in California found that virtually all Latino students want a college education, but few of Latino families had the specific knowledge to achieve this end. This knowledge was not being transmitted by high school counselors. In many cases, these students were not even enrolled in the basic college-track courses that were required for admission and 50% who were taking the right courses never took the SAT. In California, Latinos are over 30% of the k-12 population, but less than 4% of the Latino graduates in the state meet the requirements for admission to the UC system.

Other studies have found that schools tended to be less responsive to Latino parent’s needs. These parents were less likely to be aware of their child’s truancies, often because they did not have telephones, felt intimidated when approaching teachers and administrators to discuss their child, had reading difficulties, and because they were less frequently informed by schools regarding their child’s academic performance.

Culture and language of the home do not become barriers unless specific school practices and policies make them so, as Harriett D. Romo and Toni Falbo point out in a 1995 study of the school graduation of 100 Mexican-origin students and families.They found most schools over-estimated the literacy skills,knowledge of the working of the school system and other resources the family had to assist their child academically (e.g. transportation, time off of work to attend conferences, knowledge of the subject matter). In most cases, schools did not even inform parents that their children were having difficulty in school or had poor attendance, except for report cards that were sent home with the child. Even when parents were aware, they lacked the skills to effectively advocate for their child.

On the other hand, we have learned that behind the success of many Latino students are aggressive parents and supportive teachers that are not afraid to take on the educational system. My own research of 238 Mexican-origin students has shown that for those who go on to college, supportive relationships are more important than the student’s family composition, income level or intelligence scores. The parents of successful students tended set clear limits with their children, monitored their child?s peer relationships and homework activities closely, constantly reinforced the importance of school, and pushed school officials to provide their children with the necessary academic assistance. These students were also more likely to have a teacher, coach or other person in the school that was willing to take action in the family?s behalf. In contrast, L.A. Public School official, David Flores, found that over 90% of gang-involved Latino youth reported not having a single person in the school they could talk to if they had a problem.

After working 12 hours at a construction job, Ricardo Robles sits with me on his porch one summer evening and watches the neighborhood kids kick a soccer ball back and forth. He asks himself what he must do to secure the promise of education for his children. Anita is hanging on by a thread to a school system which has done little to insure she learn even the most basic skill of reading. Alma is evidence of the results of a good school and the persistence of parents that have learned to navigate the educational maze. But in this neighborhood, quality schools are the exception and there are few resources to support parents in assisting their children. It seems clear that without broad scale systemic educational reform that improves schools and directly engages and supports parents, large numbers of poor Latino youth are destined to become a part of the growing permanent underclass- not a great legacy for a country where the Statue of Liberty looms over New York as a cultural symbol that is supposed to define us.

Spring 1999

Lawrence Hernandez is an assistant professor in the Harvard Graduate School of Education. He is involved in several major school reform projects around the country to improve the achievement of Latino youth.

Related Articles

Editor’s Notes: Booknotes

On March 10, 1999, President Clinton apologized to the people of Guatemala for the support provided by the U.S. government to that country’s repressive military-backed governments…

Society and Education

As a member of UNESCO’s International Commission on Education for the Twenty-First Century, I’ve come to realize that education is about much more than books. It’s about the “four pillars of…

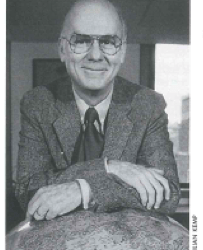

Noel McGinn’s Life of Learning

Noel McGinn, professor of education, had a normal American childhood in a small, sleepy town directly south of Miami-but 1200 miles south and across the Caribbean, in the Panama Canal Zone…