Maya Weaving Heritage

Conserving a Way of Life

Guatemala’s brilliantly colored textile tradition is one of the important threads that has united Maya civilization throughout its long history. Weavings for both ceremonial and everyday use continue to be important to Maya culture, society and ethnic identity.

Unlike Tikal’s temples and the beautiful painted classic Maya pottery one sees in museums, Maya textiles did not survive the Pre-Columbian era. They were too fragile for the humidity of the lowlands and the dampness of the tombs. Yet painted images from the past show the beginnings of the Maya textile work and ceramic figurines depict Maya women weaving with backstrap looms in the same manner that women work today.

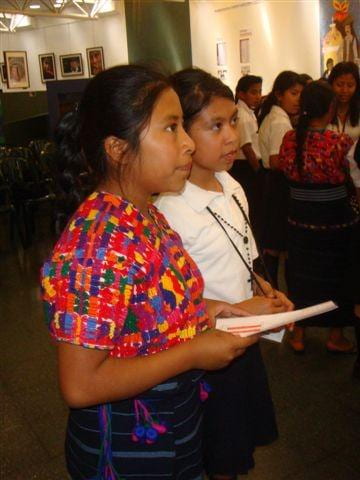

Today the Maya, who make up over half the population of Guatemala, are still weaving and some are still wearing their traditional dress. The colorful blouses, skirts, belts, hair ribbons and ceremonial cloths have myriad designs in brocade, embroidery and jaspé—birds and butterflies, animals, geometric forms.

These stunning weavings inspired a committee of the Tikal Association, a non-profit created to support the archaeological site of Tikal, to document and conserve this textile tradition. At that time, in the early 1970s, each village had its own costumes for daily wear and for ceremonial occasions but no one outside the area knew which huipil, or blouse, went with which skirt and on which occasion they were worn. To create a record, artist Carmen Pettersen painted exact watercolors of the costumes; her Norwegian husband, Leon Lind Pettersen, published the paintings and gave the book to the textile committee to raise funds for a museum. In 1976 the Ixchel Museum of Indigenous Dress opened in a rented house in the hotel district of Guatemala City.

And, in 1993, after consulting extensively with textile curators at the Metropolitan Museum of New York and after years of fundraising for the construction of a large, textile-specific building, the Ixchel Museum moved into its new building on the campus of the Francisco Marroquín University. The museum is apolitical, non-profit and independent and it supports itself which, at times, is no easy thing.

That is where my work comes in. As a member of the Board of Directors I enjoy overseeing the research and fundraising for research grants and donations. Our friends and local companies have been generous in supporting us, given that there is much need in Guatemala. For years I was also on the board of Friends of the Ixchel Museum, an American foundation that funds the museum as well as exhibiting and promoting Guatemalan textiles in the United States.

Today, the Ixchel Museum has a collection of over 6,000 woven pieces of Maya clothing from more than 115 weaving villages. The pieces date from the last days of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century to the present.

The oldest surviving textiles are made of hand-spun cotton, silk, and wool, dyed with natural dyes, and are very fragile. Years ago villages were isolated, and traditions of weaving the same designs continued for generations in each town. The women in a village all wore the same costume and daughters wore what their mothers wore; the men also had their own attire.

Today, however, with bright synthetic threads and synthetic dyes, with glittering metallic threads, with paved roads and buses careening between formerly isolated villages, the traditional dress of the Maya has been changing with great rapidity and, in some cases, disappearing entirely.

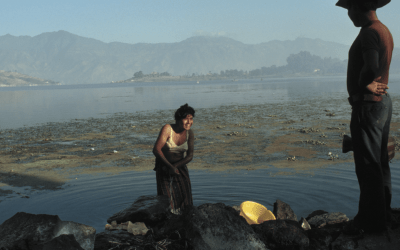

Santa Catarina Palopó, on the shores of Lake Atitlán, changed its huipil colors from red to turquoise in the 1970’s. Now the neighboring village of San Antonio Palopó, long known for its bright red textiles, is also weaving in turquoise. San Juan Atitán is changing the colors of its traditional dress as well. In Sumpango no one wears traditional clothes, and in Santiago Sacatepéquez there are no weavers left.

It can take months to weave a huipil, and there are jobs in factories that pay far more. The bundles of clothes that arrive from the United States with jeans and T-shirts make non-indigenous clothes cheaper. The modern way of life seems to be leaving weaving behind!

However, weaving remains a way of life for many Maya and, even as weaving patterns and colors change with fashion, many continue to wear spectacular textiles, but in a new way: young women no longer feel bound by the constraints of their parents and their own villages. They are reaching out to borrow what they like from weavers far away. Thus, for scholars and for the Maya themselves, it is important to conserve, document and make available to weavers and scholars the finest pieces of this age old tradition.

The Ixchel Museum exhibits the weavings, funds extensive field research and photography by staff and associated anthropologists, and publishes scholarly monographs on weaving towns. The museum has published eight technical monographs, five catalogues, and twenty information sheets on weaving towns, as well as children’s books in Spanish and two indigenous languages, children’s workbooks, and CDs of art projects. The museum also has a large photo archive and a textile library.

Reaching out to the community, the museum has a support program to buy the work of the more than 200 weavers who weave with natural brown cotton. It also has an education program in the city and in rural communities to teach 5th graders the value and beauty of their weaving heritage and raise their self-esteem.

The Ixchel Museum has won the highest civilian awards in Guatemala as well as the Premio Reina Sofia from Spain. It has received many grants for its conservation, research, and education programs.

When the museum is alive with school children who are learning about the textile tradition, trying on costumes and making small weavings, when a bus of tourists comes in and spends much needed money in the museum store, when a research monograph is presented at last after years of work, when the weavers come in to bring their work—it is exciting to be part of it all.

All of us who have worked with the museum feel it is very important to make young Guatemalans proud of their extraordinary weaving heritage. A struggling, developing country wants above all to modernize and leave the past behind, but when there is an absolutely beautiful weaving heritage that is disappearing, it is vital that tradition be valued and saved.

Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1

Holly Nottebohm ‘62 has lived in Guatemala since 1963, and has worked much of that time with the Ixchel Museum of Indigenous Dress. She edited “Radcliffe in Latin America” about alumnae in Latin America for ten years, was one of the founders of the Harvard Club of Guatemala, and was the Latin American Representative to the Harvard Alumni Association.

Related Articles

Guatemala: Editor’s Letter

The diminutive indigenous woman in her bright embroidered blouse waited proudly for her grandson to receive his engineering degree. His mother, also dressed in a traditional flowery blouse—a huipil, took photos with a top-of-the-line digital camera.

Making of the Modern: An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann

Making of the Modern An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1Related Articles

Increasing the Visibility of Guatemalan Immigrants

Guatemalans have been migrating to the United States in large numbers since the late 1970s, but were not highly visible to the U.S. public as Guatemalans. That changed on May 12, 2008, when agents of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) launched the largest single-site workplace raid against undocumented immigrant workers up to that time. As helicopters circled overhead, ICE agents rounded up and arrested …