Mining and the Defense of Afro-Colombian Territory

The Community of Yolombó, Colombia

We—an anthropologist and photographer, sister and brother—visited Yolombó in the department of Cauca, Colombia, in June 2017. Yolombó is part of a federation of ve towns known as the Corregimiento de La Toma, governed by an autonomous community council, as are many Afro-Colombian areas in the Pacific region.

When we asked María Yein Mina about mining in her community, she said, “I’ll have to divide my answer into ‘before’ and ‘after’ the arrival of the retros,” the backhoes that outsiders brought to the Ovejas River beginning in the late 1980s.

Until then, members of the five towns practiced a balanced economy of mining, shing and subsistence agriculture along with a few commercial crops such as cof- fee. People usually worked on the farm on Mondays and Tuesdays and spent the rest of the week mining and fishing. At first some members of the community fell into the trap of the retros, neglecting their farms in order to mine the strata of gold particles exposed by the machinery in the banks of the Ovejas River. But then they realized that this way led to ruin: the banks were churned up, gold was becoming scarce, and people no longer wanted to swim or fish because of mercury in the water. They petitioned the authorities to enforce environmental laws, without success.

Led by the younger residents of Yolombó, the community went en masse to the river, boarded the machines and compelled the owners to turn them off. In 2014, a group of fteen women traveled, mostly on foot, to a series of other Afro-Colombian communities also faced with the imposition of mechanized alluvial mining in their territories. Strengthened by numbers, they arrived in Bogotá to pressure the national government to act.

The media called their movement “The March of the Turbans,” in reference to the scarves many of the women wrapped around their heads in traditional Afro-Colombian fashion. The marchers reached out for national and international support.

Their efforts worked, perhaps too well. They had hoped for administrative action that would compel the backhoes’ owners to remove them; the police simply showed up and burned the machinery. As a consequence, leaders of the movement received multiple death threats.

The people of La Toma had to defend their territory on a second front, this one underground. This conflictive history had historical roots. In the early 2000s, the multinational company AngloGold Ashanti had begun taking core samples in the area, sending agents into the community as social workers, festival sponsors and contributors to public works such as repairing the highway. This is a common— and from the corporate perspective, widely accepted—strategy, but one that was viewed with suspicion in the villages of La Toma. Sure enough, they soon learned that the Ministry of Mines had granted mining titles to AngloGold Ashanti and to private citizens with no links to the community. These concessions entailed the removal of the families living there—practically the entire town of La Toma. In 2009, the government sent the police to displace the residents. The community had stood its ground, facing security forces with crowbars and machetes in hand.

They had also fought back through the courts, filing lawsuits on grounds of loss of livelihood and the lack of prior consultation, in violation of the International Labor Organization convention to which Colombia is a signatory. In 2010, the Constitutional Court accepted their arguments and declared that the mining titles must be suspended. Again, leaders received death threats in the form of pamphlets, phone calls and text messages.

In the face of these threats, residents formed the Maroon Guard. The word “maroon” refers historically to communities of escaped slaves, but its meaning has expanded to refer to black resistance in Latin America and the Caribbean in its many forms. The Guard is a community police force of about forty young men and women, which manages internal conflicts and protects the community from outside threats. They based their movement on the Palenque Police, set up by residents of the historic maroon community of San Basilio de Palenque. The Maroon Guard also shares methods with the Indigenous Guard, an organized force within the nearby reservations of the Nasa people that has confronted leftist guerrillas, right-wing paramilitaries and the state in defense of native territory.

The families that live in the ve towns in the jurisdiction of La Toma—Yolombó, Gelima, El Hato, Dos Aguas and La Toma—have inhabited this region on the Pacific coast of Colombia since the early 17th century, when they were brought as slaves to work the Gelima gold mine and surrounding farms. The gold from Gelima and other smaller mines enriched the city of Popayán, and the whole Real Audiencia de Quito, which included parts of southern Colombia, current-day Ecuador and northern Peru. The Jesuits mainly owned the mines until their expulsion from the Americas in 1767.

Francia Márquez Mina, community member, lawyer, and recipient of the National Prize for the Defense of Human Rights in Colombia, told us that although mining brought their ancestors from Africa as slaves, it also made them free; many bought their liberty by mining for gold in the Ovejas River, while others escaped and lived as maroons. Their families, and the families of those emancipated in the mid-19th century, bought the land from the proceeds of mining and defended it from successive attempts to displace them over the centuries.

In recent years these attempts have become even more aggressive. Beginning in the early 2000s, a combination of high prices for metals, more ef cient technologies, and greatly improved security conditions have made Colombia newly attractive for transnational corporations. The Colombian government prioritizes large-scale resource extraction as a central feature of its economic development agenda. The current mining code was drafted in 2001 in collaboration with Canadian advisers, and favors large-scale projects over traditional mining. Foreign mining companies now see Colombia as a new frontier.

In all this planning, the government and foreign corporations tend to ignore local communities that have been mining gold for centuries. At least 350,000 Colombians make their livelihood directly through small-scale gold mining activities, with many more depending on them through family ties and commerce. These miners have dense social and territorial relations with gold, customary rights, and long histories.

As the “mining locomotive” (to use President Juan Manuel Santos’s phrase) gained momentum, these local miners have come into conflict with multinational corporations, with the Colombian state, and with companies from outside their communities who bring in mechanized and highly destructive machinery such as the retros. Yolombó is just one place among many where these conflicts have come to a head.

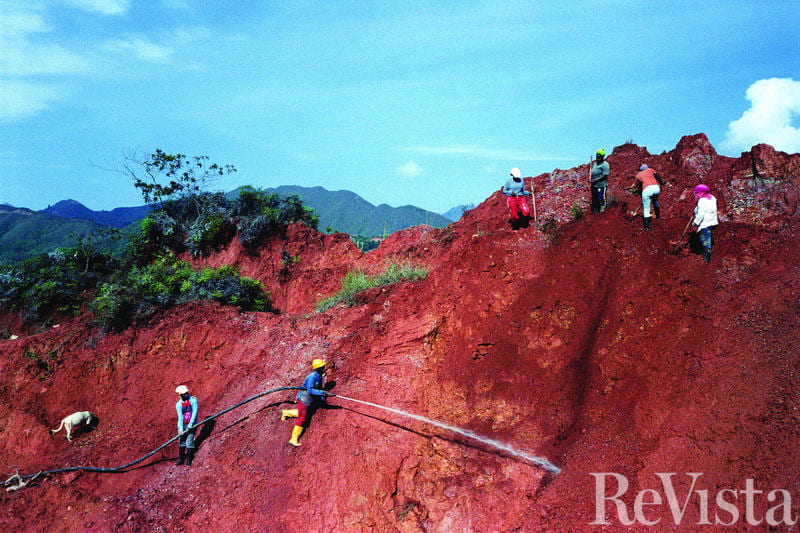

When we visited in June 2017, the river was too high for alluvial mining, so we went to an area close to the school in Yolombó, to see a form of mining called minería de chorreo or “water-jet mining.” We watched a group of some fteen miners, members of several families who have owned land in Yolombó for centuries, directing jets of water at the hill to form a channel of red mud at its base. They then use bateas (a wooden pan used in min- ing since Pre-Columbian times) and almocafres (a traditional tool shaped like a garden hoe) to separate the gold. Instead of mercury, they use the viscous sap of a plant known as escoba babosa, traditionally used in Colombia as an anti-in aflammatory, that also helps separate gold from its surroundings. By these methods, they can mine for decades in the same area.

The threats have continued. Sent by email from unknown parties, they accuse the community of “opposing progress” and undermining the government’s plans for development through foreign investment. For her safety, Francia Márquez no longer lives in the area and travels accompanied by armed bodyguards provided by the state.

AngloGold Ashanti appears to have left the region and its titles have been suspended, but not cancelled. Sabino Lucumí Chocó, president of the La Toma Community Council, calls these titles “a permanent threat” to the survival of the community.

Against this uncertain future, the towns remain organized. Among other things, the community council conducts media relations and legal actions, promotes ancestral culture for youth, and is planning an independent environmental school, to be called “La Batea.”

Winter 2018, Volume XVII, Number 2

Stephen Ferry is co-author of La Batea (Icono/Red Hook, 2017), his third book. He has contributed to the New York Times, GEO, TIME and National Geographic. He was the winner in the professional category of the 2017 Best of ReVista photo contest. His website is stephenferry.com.

Elizabeth Ferry is Professor of Anthropology at Brandeis University. Her research interests lie in value, materiality, mining, nance, Mexico, Colombia and the United States. She is co-author of La Batea (Icono/Red Hook, 2017), her third book. Her website is elizabeth-ferry.com

Related Articles

Afro-Latin Americans: Editor’s Letter

My dear friend and photographer Richard Cross (R.I.P.) introduced me to the unexpected world of San Basilio de Palenque in Colombia in 1977. He was then working closely with Colombian anthropologist Nina de Friedemann, and I’d been called upon by Sports Illustrated to…

Witches, Wives, Secretaries and Black Feminists

The issue of gender has been front and center for me, both as a subject of my fieldwork on black politics in Latin America, and how I conducted that research, particularly in how I…

Compañeros En Salud

English + Español

I have lived in non-indigenous rural Chiapas in southern Mexico since 2013, working with Compañeros En Salud (CES)—a Harvard af liated non-profit organization that partnered with…