Mockuments

An Alternative to the Statue Quo

- Liberty Doll Workshop. Source: Marcela Fernanda Pardo García

- Liberty Doll. Source: Marcela Fernanda Pardo García

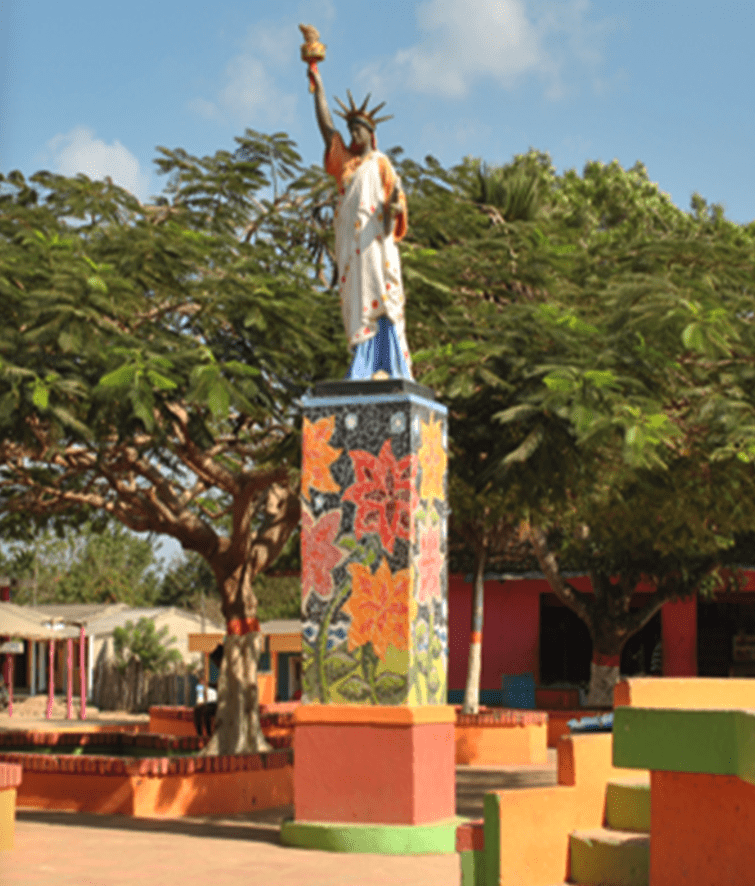

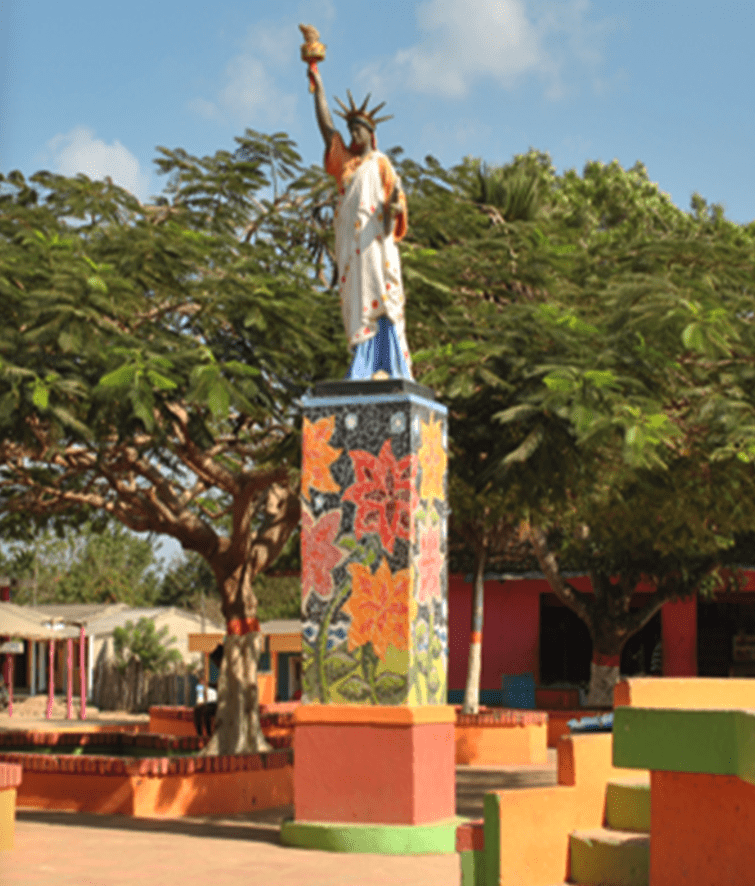

On June 12, 2014, a ten-foot white fiberglass replica of the Statue of Liberty makes its entry into Libertad, a small town on Colombia’s Atlantic coast, after a journey through half the country moored on the roof of a ’79 Land Rover.

The monument is welcomed with a mix of amazement and enthusiasm by a group of Black women denouncing the systematic practice of sexual violence by paramilitary groups in the region: Nergina Gúzman, Isabel Martínez, Modesta Sarmiento and Adriana Porras. They decide to install it in the central park of the town. From that moment on, the Statue of Liberty becomes its doll, its saint and its marucha: the icon of the United States turns into the protector of feminist struggles in the midst of the war in Colombia.

This little-known story—which I learned from the research that Marcela Fernanda Pardo García carried out under my mentorship at the National University of Colombia—begins on July 1, 1998, at the El Dorado airport in Bogotá, when a group of officials seize the strange object. The carved glass lamp instead of the torch reveals its final destination: the mansion of some drug trafficker, as a smuggling trophy at the frontier of the American dream.

After three years of captivity in the basements of the National Tax and Customs Division (DIAN), the state makes an official donation of the statue to the Progresar Foundation, an organization of former combatants of the People’s Liberation Army (EPL), a guerilla group demobilized after one of the many peace processes in the recent history of the country. Nobody knows what to do with this artifact, too bulky for the small headquarters, too symbolic to throw it away. When the Progresar foundation shuts down, its leader Idelfonso Henao ends up keeping the statue for more than ten years in his office and then in a warehouse. Finally he hands it over to the plastic artist Camilo Conde with these words:

“Add something to that, let’s see if we can sell it.”

Conde at this time is accompanying the Black women of Libertad in their process to go from being victims of sexual violence to being agents of cultural and social change. A Statue of Liberty for the women of Libertad in their liberation process: what appears almost like a play on words soon becomes a project.

However, in a beginning the irruption of the statue in town faces controversy and suspicions. In those days people are preparing to commemorate Resistance Day for the very first time, to remember how 10 years before a group of neighbors had shaken off the paramilitary yoke, killing with sticks and stones “Alias Diomedes,” one of the most ferocious commanders. With the recent peace process, it is now possible to remember that episode of the rescue of popular dignity. But what does that intrusive monument have to do with it?

Up until that point, historical memory reports had not included the issue of sexual violence. These stories were never confessed by the paramilitaries and were shameful for the victims’ families, made up of silences and insinuations. Only thanks to the songs of maruchas and the dances to the rhythm of bullerengue that accompanied the painting and installation of the Statue of Liberty in the park, the debate is opened and the community comes to recognize the victimization of the women of the town and their courage in recounting their experiences as part of the resistance to the armed conflict.

Through a collective work of women, young people and children led by Camilo, the Statue of Liberty strips away its neoclassical costumes and its imperialist stance, to resemble a black maroon in a white suit with floral decorations of cheerful colors, always ready for dance and enjoyment. Today the Doll of Liberty—as the townspeople call her—is the town’s greatest attraction. Every visitor is told the story of the women of Libertad who knew how to denounce the horrors of war and regain their own identity and that of an entire community.

***

The Christ of Bojayá. Source: Jesús Abad Colorado, 2002 In: ¡Basta Ya! Colombia: Memories of war and dignity General Report Historical Memory Group. Bogotá: National Center for Historical Memory, 2013, p.88 https://www.centrodememoriahistorica.gov.co/descargas/informes2013/bastaYa/basta-ya-colombia-memorias-de-guerra-y-dignidad-2016.pdf

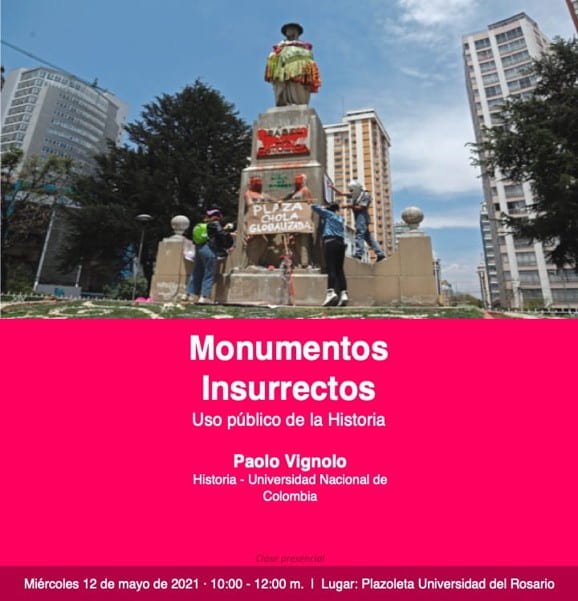

I have been thinking over and over again about the story of the Doll of Liberty throughout those months that have marked the end of what I like to call the “statue quo.” Monuments have lost their innocence in the eyes of the public. No one can go under a statue anymore without wondering if and when it will be torn down. Hundreds of monuments have been target of derision, anger and indignation during the popular revolts that have shaken the Americas, from north to south. Graffitis, escraches, hammer blows, hangings … rumbles of revolution in the iconosphere, which shake an institutional memory that offends the victims of yesterday and today.

Now, toppling a statue can be a powerful emancipatory gesture to open up unavoidable questions about colonization, slavery and exploitation. Nevertheless, as the act is repeated, its political strength is wearing down, its media impact as well. It is time to ask ourselves what we are going to do with these statues fallen from grace. And with the empty pedestals of our streets in turmoil.

Repairing monuments, cleaning them, and putting them back in place is no longer an option. It would be an act of restoration, the very denial of social mobilizations and their reasons.— as it happened in Bogotá two years ago. Then-Mayor Enrique Peñalosa, undaunted by the ridicule, decided not only to clean up protest graffitis from the sculpture of Christopher Columbus, but he also spent a fortune to turn it 22.5 degrees to the west, to let the admiral’s hand indicate the “true” route to the Indies! Now —after a recent attempt of dethronement by the Misak Indians—the statue of Columbus is stored in the old abandoned railway station in the company of Queen Isabel and an equestrian Bolívar, awaiting an uncertain destination.

Likewise, I refuse to think that the way forward is to replace the statues of the bad guys with the statues of the good guys, the conqueror with the indigenous woman, the winner celebrated yesterday with the recently rescued loser, in a sad mimesis of the aesthetics of the dominators. Or, worse still, to put them side by side, in a monumental apotheosis of the politically correct.

Hugo Chávez was outraged when in 2004 some of his supporters hanged the sculpture of Christopher Columbus, only to vindicate the act eleven years later. On the empty pedestal he had the effigy of the Guaicaipuro indigenous chief erected. The initial intention of the authors of the gesture, however, was different: to replace the Genoese admiral with a tribute to bread with mortadella, an essential gastronomic contribution of Italian migrants to Venezuela.

Yes, because icons are ambivalent: although we all know how to recognize them, their meanings change drastically depending on the context. That is why the decision of the president of Argentina Cristina Fernández to replace the gigantic effigy of Columbus in front of the Casa Rosada with another of Juana Azurduy, a popular heroine of independence, unleashed a clash with the then-mayor of Buenos Aires, Mauricio Macri, who claimed its importance as a tribute to the Italian presence in the country.

Posters of Insurrectionary Monuments, organizers of Class to the Street and students of the Department of History of the National University of Colombia

From contemporary art, meaningful proposals of counter-monuments and anti-monuments for the 21st century sprout, such as the famous works of Krzysztof Wodiczk and Doris Salcedo. For example, Oscar Muñoz’s protographs come to my mind: ephemeral faces that are lost in the whirlpool of a sink’s drainpipe, portraits that fade away despite the efforts of a hand that keeps on drawing them, visages that only appear with the breath of those who look at them. Fragile, fickle images that know how to look at themselves in the mirror of others. Like us humans, like our memories.

Or the mutilated Black Christ of the Church of Bojayá, where more than 80 people were killed in 2002 by the explosion of a gas pipette launched by the 58th front of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), in a clash with the paramilitary Bloc Elmer Cárdenas. “The Christ of Bojayá in some way is our Guernica,” affirms the photographer Jesús Abad Colorado. The inhabitants of Bojayá preserve that fragment of a body figure twice martyred as a relic and monument to the victims, in front of which guerrilla commanders, paramilitary leaders, state authorities, even the Pope himself have had to prostrate themselves.

***

“Indigenous Misak do it again: they demolished the statue of Jímenez de Quesada in Bogotá.” Photo: periodicovirtual.com

The story of the Doll of Liberty allows us to think about other options too, in which statues and pedestals become playful and festive opportunities. Thanks to the languages of farce, satire and irony, memory is translated into memes and the monument becomes mockument: a carnivalesque device that breaks down the claims of eternity of a static and statuary history through performances that privilege laughter, underlining silences about the past, telling present truths and opening questions about possible futures.

When the activists of the Collective Mujeres Creando wrapped the sculpture of Isabella the Catholic in La Paz (Bolivia) with a Andean skirt, a yellow blanket, a bundle of carrying cloth and a hat, they managed to question the inhabitants of the Bolivian capital at the same time on the legacy of Spanish colonialism, the contemporary tragedy of femicides and the right to a pension for housewives.

Sometimes an Afro wig is enough, like the one that Afro-Colombian artist Nelson Fory has been putting on heroes and conquerors in Cartagena, Cali and Bogotá since 2008. With this festive look, the statues of Pedro de Heredía, Cristobal Colón and Simón Bolivar almost seemed to dance salsa to the rhythm of Joe Arroyo’s La Rebelión,

Photo by Amada Carolina Pérez Benavides

In other cases, the staging is more complex. In 2018 at the Pasto carnival the float “El Colorado” triumphed. In a hubbub of mobile mannequins and festive colors it staged a dark side of the country’s history: the massacre of the Black Christmas of 1822, perpetrated by the troops of General Antonio José de Sucre, under express orders of Simón Bolívar.

Statues of Liberty turned into black maroons, European queens dressed as Andean women, heroes of independence in a carnivalesque fashion: mockuments share with their cousins the mockumentaries the ability to undermine established genres, blur the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction and, above all, actively play with their audience.

And here I am surprised to look at the statues with a certain tenderness. I already find them more charming, I confess. Tragic and ancient creatures, Golems who have carried the horrors of the past and now give their first sobs in the world. That is why I do not believe that it is necessary to rage against them either. If the beheading of the tyrant can be a revolutionary gesture, torture is just pure cruelty. Furthermore, iconoclasm made system unconsciously ends up admitting a reverential fear in the face of the very powers of the sacred that it wants to overthrow.

In most cases they are still quite ugly, it is true. They are made in the image and likeness of unscrupulous merchants, corrupt politicians, kings and soldiers with bloodstained hands. Yet, even the most frightening statue has the right to a second inauguration: uncovering his old suits to shine another countenance, poiesis of the political into the poetic. If the statues have detached themselves, even for a few hours, from the epistemic cages and the interpretative chains that tied them to an official reading of what happened, now they can become protagonists of what is happening and what could happen.

Two months ago—in the middle of a social protest—a group of Misak indigenous people knocked down the statue of the conqueror Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, supposed founder of Bogotá. Around its empty pedestal a street class became a circle of word, which later gave way to a number of consultation tables with the mayor’s office. From this citizen lab, the most varied proposals are emerging: community gardens, changes in toponomastics, indigenous mortuary rituals, declarations of sacred sites in urban space.

Indigenous Mortuary around the statue of Gonzalo Jímenez de Quesada. Photo Carlos Guillermo Paramo

The following step will be to intervene the pedestal, whose emptiness refers us to the voids of official history. The idea is that we can play to collectively rethink our history. Any individual, group or association that has a proposal to re-signify patriotic symbols and founding myths of the country and of its capital will be allowed to climb on the pedestal and express it through speeches, music, poetry, performances or installations.

The thunderous silence of a masculine, bombastic, often militaristic memory will be replaced by a polyphony of heterogeneous, dissonant and festive voices: protest songs, football bar choirs, parodies of nineteenth-century harangues, puppets and rag dolls… The empty pedestal will offer each one their 15 minutes of monumental glory: the Creole version of the American dream by Andy Wahol and the Anglo-Saxon speaker’s corners.

And the statue? Right now it is lying half down in the parking lot of the local mayor’s office. However, we would like the effigy to be able to travel again through the places of the conquest of Gonzalo Jímenez de Quesada 500 years ago: from Santa Marta on the Caribbean coast to the slopes of the Sierra Nevada, and then go up the Magdalena River to the plateau where the Muisca civilization was, heading to the plains of the Orinoco in search of El Dorado….

At each stage a collective performance organized with groups and communities as a fun and ironic way to reflect on the conquest, this past that does not pass. And also the opportunity, as many indigenous populations ask—to promote a process of healing and reconciliation, just now that the Truth Commission is about to make public its report on the structural causes of the Colombian armed conflict and the paths towards civil coexistence.

And who knows if in his pilgrimages through the towns that he conquered with blood and fire half a millennium ago, the puppet of Jímenez de Quesada is not going to meet the Doll of Liberty in the middle of a great collective celebration, as a way to exorcise once and for all past and present colonialisms.

MOCKUMENTS

UNA ALTERNATIVA AL ESTATUA QUO

Por Paolo Vignolo

- Taller de la muñeca de Libertad. Fuente: Marcela Fernanda Pardo García

- Muñeca de Libertad. Fuente: Marcela Fernanda Pardo García

El 12 de junio de 2014, una réplica de la Estatua de la Libertad de tres metros en fibra de vidrio blanca hace su entrada en Libertad, un pequeño pueblo de la costa atlantica de Colombia, luego de una travesía por medio país amarrada en el techo de un Land Rover modelo ‘79.

El monumento es recibido con un mixto de asombro y entusiasmo por un grupo de mujeres negras que están denunciando la práctica sistemática de violencia sexual por parte de grupos paramilitares en la región: Nergina Gúzman, Isabel Martínez, Modesta Sarmiento y Adriana Porras. Deciden instalarla en el parque central del pueblo. Desde ese momento la Estatua de la Libertad se vuelve su muñeca, su santa y su marucha: el icono de Estados Unidos se transforma en la protectora de las luchas feministas en medio de la guerra en Colombia.

Esta historia poco conocida—que aprendí del trabajo de investigación que Marcela Fernanda Pardo García llevó a cabo bajo mi tutoría en la Universidad Nacional de Colombia- inicia el 1 de julio de 1998 en el aeropuerto El Dorado de Bogotá, cuando un grupo de funcionarios decomisan el extraño objeto. La lámpara en vidrio tallado en sostitución de la antorcha delata su destino final: la mansión de algún narcotraficante, como trofeo de contrabandos a la frontera del sueño americano.

Luego de tres años de cautiverio en los sótanos le la División de Impuestos y Aduanas Nacionales (DIAN), el estado hace oficial donación de la estatua a la Fundación Progresar, una organización de ex combatientes del Ejercito Popular de Liberación Popular (EPL), una guerrilla desmovilizada luego uno de los muchos procesos de paz de la historia reciente del país. Nadie sabe qué hacer con este artefacto, demasiado voluminoso para la pequeña sede, demasiado simbólico para botarlo a la basura. Cuando la fundación Progresar cierra, su lider Idelfonso Henao termina guardando la estatua por más de diez años en su oficina y luego en una bodega. Finalmente se la entrega al artísta plástico Camilo Conde con esas palabras:

“Agréguele algo a eso, a ver si la vendemos.”

El Cristo de Bojayá. Fuente: Jesús Abad Colorado, 2002 En: ¡Basta Ya! Colombia: Memorias de guerra y dignidad Informe General Grupo de Memoria Histórica. Bogotá: Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica, 2013, p.88 https://www.centrodememoriahistorica.gov.co/descargas/informes2013/bastaYa/basta-ya-colombia-memorias-de-guerra-y-dignidad-2016.pdf

Conde en este tiempo está acompañando a las mujeres negras de Libertad en su proceso para pasar de ser victimas de violencia sexual a ser agentes de cambio cultural y social. Una Estatua de la Libertad para las mujeres de Libertad en su proceso de liberación: lo que surge casi como un juego de palabras se convierte pronto en un proyecto.

Sin embargo, en un comienzo la irrupción de la estatua en el pueblo se enfrenta a polémicas y sospechas. En esos días la gente se está preparando a conmemorar por primera vez el Día de la Resistencia, para recordar como 10 años antes un grupo de vecinos se había sacudido del yugo paramilitar, matando a palos y piedras “Alias Diomedes”, uno de sus comandantes más feroces. Con el reciente proceso de paz, ya se puede hacer memoria de aquel episodio de rescate de la dignidad popular. Pero, ¿Qué tiene a que ver aquel monumento intruso?

Hasta ese entonces los relatos de memoria histórica no habían incluido la cuestión de la violencia sexual. Eran historias jamás confesadas por los paramilitares y vergonzosas por las familias, hecha de silencios e insinuaciones. Solo gracias a los cantos de maruchas y los bailes al ritmo de bullerengue que acompañan la pintada y la instalación de la Estatua de la Libertad en el parque, se abre el debate y la comunidad llega a reconocer la victimización de las mujeres del pueblo y su valentía en contar sus vivencias como parte de la resistencia al conflicto armado.

A través de un trabajo colectivo de mujeres, jovenes y niños liderado por Camilo, la Estatua de la Libertad se despoja de sus trajes neoclásicos y su postura imperialista, para tomar las semblanzas de una negra cimarrona de traje blanco, con adornos floreales de colores alegres, siempre lista para el baile y para el goce. Hoy en día la Muñeca de Libertad –asi le dicen- es el mayor atractivo del pueblo. A todo visitante se le cuenta la historia de las mujeres liberteñas que supieron denunciar los horrores de la guerra y reconquistar la identidad propia y de toda una comunidad.

***

He pensado una y otra vez a la historia de la Muñeca de Libertad a lo largo de esos meses que han marcado el fin de lo que me gusta llamar el “estatua quo”. Los monumentos han perdido su inocencia a los ojos de la ciudadanía. Ya nadie puede pasar bajo una estatua sin preguntarse si y cuando será derribada. Cientos de monumentos han sido motivo de escarnio, rabia e indignación de las revueltas populares que han sacudido a las Américas, de norte a sur. Pintadas, escraches, martillazos, ahorcamientos… retumbos de revolución en la iconosfera, que ponen a temblar una memoria institucional que ofende a las víctimas de ayer y de hoy.

Ahora bien, derrocar una estatua puede ser un gesto emancipatorio potente para abrir a preguntas ineludibles sobre la colonización, la esclavitud y la explotación. Sin embargo, a medida que el acto se repite su fuerza política se va agotando, su impacto mediatico también. Es tiempo de interrogarnos sobre qué vamos a hacer con estas estatuas caídas en desgracia. Y con los pedestales vacíos de nuestras plazas en tumulto.

Reparar los monumentos, limpiarlos y volverlos a poner en su lugar ya no es una opción. Sería un acto de restauración, la negación misma de las movilizaciones sociales y de sus razones. Como pasó en Bogotá hace dos años, cuando el entonces alcalde Peñalosa, impávido frente al ridículo, decidió no solo hacer repulir la escultura de Cristóbal Colón de los grafitis contestatarios- sino gastó una fortuna para voltearla de 22,5 grados hacia occidente, ¡Para que la mano del almirante indicara la “verdadera” ruta hacia las Indias! Ahora – luego de un intento reciente de destronamiento por parte de los indigenas Misak- la estatua del Colón está guardada en la antigua estación de ferrocarriles abandonada, en compañía de la reina Isabel y de un Bolivar ecuestre, a la espera de un destino incierto.

Igual, me niego a pensar que el camino a seguir sea sustituir las estatuas de los malos con las estatuas de los buenos, el conquistador con la mujer indígena, el vencedor celebrado ayer con el vencido recién rescatado, en una triste mimesis de la estética de los dominadores. O, peor aún, de ponerlos uno al lado del otro, en una apoteosis monumental de lo políticamente correcto.

Afiches de Monumentos Insurrectos, organizadores de Clase a la Calle y estudiantes del Departamento de Historia de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia

Hugo Chávez se escandalizó cuando en 2004 algunos simpatizantes suyos ahorcaron la escultura de Cristobal Colón, solo para reivindicar el acto once años más tarde. En el pedestal vacío hizo erigir la efigie del cacique indígena Guaicaipuro. La intención inicial de los autores del gesto, sin embargo, era otra: sustituir al almirante genovés con un tributo al pan con mortadela, imprescindible contribución gastronómica de los migrantes italianos a Venezuela.

Sí, porque los iconos son ambivalentes: aunque todos sepamos reconocerlos, sus significados cambian drásticamente según el contexto. Por eso la decisión de la presidenta de Argentina Cristina Fernández de remplazar la gigantesca efigie de Colón frente a la Casa Rosada por otra de Juana Azurduy, heroína popular de la independencia, desató un pulso con el entonces alcalde de Buenos Aires, Mauricio Macri, que reivindicaba su importancia como homenaje a la presencia italiana en el país.

Desde el arte contemporaneo brotan propuestas fecundas de contra-monumentos y anti-monumentos para el siglo XXI, como las celebres obras de Krzysztof Wodiczk y de Doris Salcedo. Se me ocurren por ejemplo las protografias de Oscar Muñoz: rostros efímeros que se pierden en el remolino del tubo de desagüe de un lavamanos, retratos que se desvanecen a pesar de los esfuerzos de una mano que los sigue dibujando, caras que solo aparecen con el aliento de quien las mira. Imágenes frágiles, volubles, que saben mirarse a sí mismas en el espejo de los demás. Como nosotros los humanos, como nuestras memorias.

O el Cristo Negro mutilado de la Iglesia de Bojayá, donde más de 80 personas fueron asesinadas en 2002 por la explosión de una pipeta de gas lanzada por el frente 58 de las Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC), en un enfrentamiento con el Bloque paramilitar Elmer Cárdenas. “El Cristo de Bojayá de alguna forma es nuestro Guernica” afirma el fotografo Jesús Abad Colorado. Los habitantes de Bojayá conservan ese fragmento de figura de cuerpo dos veces martirizado como reliquia y monumento a las víctimas, frente a la cual han tenido que prostrarse comandantes guerrilleros, jefes paramilitares, autoridades del Estado, hasta el mismo Papa.

***

“Indigenas Misak lo vuelven a hacer: derribaron estatua de Jímenez de Quesada en Bogotá”. Foto: periodicovirtual.com

La historia de la Muñeca de Libertad nos permite pensar también en otras posibilidades, donde estatuas y pedestales se vuelven ocasión de juego y de fiesta. Gracias a los lenguajes de la farsa, la sátira y la ironía, la memoria se convierte en memes y el monumento se vuelve mockument: un dispositivo carnavalesco que desmorona las pretenciones de eternidad de una historia estática y estatuaria a través de performancias que privilegian la risa, para subrayar los silencios sobre el pasado, decir verdades sobre el presente y abrir preguntas sobre futuros posibles.

Cuando las activistas del Colectivo Mujeres Creando arroparon a la escultura de Isabel la Católica en la Paz (Bolivia) con una pollera, una manta amarilla, un atado de aguayo y un sobrero, lograron interprelar a los habitantes de la capital boliviana a la vez sobre el legado del colonialismo español, la tragedia contemporánea de los feminicidios y el derecho a una pensión para las amas de casas.

A veces es suficiente una peluca afro, como la que desde 2008 el artista afroccolombiano Nelson Fory le va poniendo en Cartagena, Cali e Bogotá a próceres y conquistadores. Con esta pinta festiva las estatuas de Pedro de Heredía, Cristobal Colón y Simón Bolivar casi parecían tirar pasos de salsa al ritmo de La Rebelión de Joe Arroyo.

En otros casos la puesta en escena es más compleja. En 2018 en el carnaval de Pasto triunfó la carroza “El Colorado” que, en una algarabia de maniquis móviles y colores festivos, ponía en escena un lado oscuro de la historia patria: la masacre de la Navidad Negra de 1822, perpretada por las tropas del general Antonio José de Sucre bajo ordenes expresas de Simón Bolívar.

Estatuas de la Libertad convertidas en negras cimarronas, reinas europeas vestidas de chola andinas, héroes de la independencia con tumbao de carnaval: el mockument comparte con su primo hermano el mockumentary la capacidad de socavar los géneros establecidos, borrar las fronteras entre ficción y no ficción y, sobre todo, jugar activamente con su público.

Foto de Amada Carolina Pérez Benavides

Y acá me sorprendo a mirar las estatuas con cierta ternura. Ya me resultan más simpáticas, lo confieso. Criaturas trágicas y antiguas, Golems que han cargado con los horrores del pasado y ahora dan sus primeros sollozos por el mundo. Por eso tampoco creo que haya que inferir contra ellas. Si la decapitación del tirano puede ser gesto revolucionario, la tortura ya es pura crueldad. Además, la iconoclastia hecha sistema inconscientemente termina admitiendo un temor reverencial frente a los mismos poderes de lo sagrado que quiere derribar.

En la mayoría de los casos siguen siendo bastantes feas, es cierto. Están hechas a imagen y semejanza de mercaderes sin escrúpulos, políticos corruptos, reyes y militares con las manos manchadas de sangre. Empero, hasta la estatua más espantosa tiene el derecho a una segunda inauguración: destaparse de sus viejos trajes para relucir otro semblante, poiesis de lo político en lo poético. Si las estatuas se han desprendido, aunque por pocas horas, de las jaulas epistémicas y de las cadenas interpretativas que las ataban a una lectura oficial de lo que pasó, ahora pueden volverse protagonistas lo que está pasando y podría pasar.

Hace dos meses –en pleno estallido social- un grupo de indigenas Misak tumbó la estatua del conquistador Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, supuesto fundador de Bogotá. Alrededor de su pedestal vacío una clase a la calle se transformó en un circulo de palabra, que luego dio paso a una serie de mesas de concertación con la alcaldía. Desde este laboratorio ciudadano están surgiendo las propuestas más variadas: huertas comunitarias, cambios en la toponomastica, mortuarias indigenas, declaraciones de sitos sagrados en el espacio urbano.

El paso a seguir será intervenir el pedestal, cuyo vacío nos remite a los vacíos de la historia oficial. La idea es que podamos jugar a repensar colectivamente nuestra historia. Cada individuo, grupo o asociación que tenga una propuesta para reseignificar los simbolos patrios y los mitos fundacionales del país y de su capital podrá treparse en el pedestal y expresarla a través de discursos, música, poesía, performances o instalaciones.

Mortuorio Indígena alrededor de la estatua de Gonzalo Jímenez de Quesada. Foto Carlos Guillermo Paramo

El estruendoso silencio de una historia varonil, grandilocuente, a menudo militarista va a ser remplazada por una polifonía de voces heterogeneas, disonantes y festivas: canciones de protesta, coros de barras futboleras, parodías de arrengas decimonónicas, titeres y muñecos de trapo … El pedestal vacío ofrecerá a cada quien sus 15 minutos de gloria monumental: la versión criolla del sueño americano de Andy Wahol y de los speaker’s corners anglosajones.

¿Y la estatua? En este momento yace medio achacada en el parqueadero de la alcaldía local. Sin embargo nos gustaría que la efigie pudiera volver a viajar por los lugares de la conquista de Gonzalo Jímenez de Quesada hace 500 años: desde Santa Marta en la costa Caribe hasta las laderas de la Sierra Nevada, para luego remontar el río Magdalena hasta el altiplano de la que fue la civilización Muisca, rumbo a las llanuras del orinoco en busca de El Dorado…

En cada etapa una puesta en escena colectiva organizada con grupos y comunidades: una manera divertida e irónica para reflexionar sobre la conquista, este pasado que no pasa. Y también la oportunidad, como piden muchas poblaciones indigenas- para propiciar un proceso de sanación y reconciliación, justo ahora que la Comisión de la Verdad está a punto de volver público su informe sobre las causas estructurales del conflicto armado colombiano y los caminos hacia una convivencia civil.

Y quien sabe si en sus romerías por los pueblos que conquistó a sangre y fuego hace medio milenio, el fantoche de Jímenez de Quesada no se vaya a encuentrar con la Muñeca de Libertad, en medio de una gran fiesta colectiva que exorcize de una vez por todas los colonialismos pasados y presentes.

Spring/Summer 2021, Volume XX, Number 3

Paolo Vignolo is associate professor at the Department of History at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogota. His fields of research and creation deal with public history, memory studies and cultural heritage with a focus on live arts, performance and geographic imaginaries. He was the 2012-13 Santo Domingo Visiting Scholar at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS) at Harvard University.

Paolo Vignolo es profesor asociado del Departamento de Historia de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Su trabajo de investigación y creación está enfocado en el uso público de la historia, la memoria histórica y el patrimonio cultural, con énfasis en artes vivas, performance e imaginarios geográficos. Ha sido Santo Domingo Visiting Scholar 2012-13 del David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS) de la Universidad de Harvard.

Related Articles

My cry into the world

English + Español

It was September 20, 2019. “One hundred, two hundred, three hundred, four hundred….” That was how we felt and that was how we counted in the face of the irremediable absences provoked…

When Decolonization Meets an Immovable Monument

It was early October 2013, well before the present wave of toppling statues in the name of decolonization gained momentum in the United States and the United Kingdom…

The Ghosts of Canudos: A War Memorial

English + Español

Just like in the Argentine pampas or in the plains of Venezuela, the space in the Brazilian sertão, in the country’s Northeast region, has no limits. The hard brown land seems to stretch out in all directions, undulating endlessly, and the feeling it provokes is inevitably one of melancholy