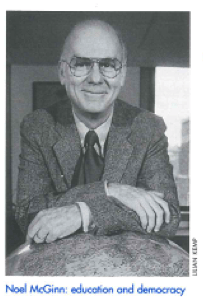

Noel McGinn’s Life of Learning

Helping Nations Plan Education and Prepare for Democracy

Noel McGinn, professor of education, had a normal American childhood in a small, sleepy town directly south of Miami-but 1200 miles south and across the Caribbean, in the Panama Canal Zone.

“I grew up in Gatún, a small town two miles from Colón on the Atlantic coast. It was very quiet.” His kindly features crease with a smile as he tells me about being born and growing up in Panama for seventeen years. Curiously, he did not have to learn Spanish until his graduate studies in the United States because he had few opportunities to interact with local Panamanians.

“I went back for the first time just last month,” he says, “and the town looks the same as ever! It’s really a different world.” McGinn chuckles. If the town hasn’t changed much, he himself certainly has, traveling back to his birthplace as a consultant to Panama’s ministry of education.

Given his beginnings, McGinn seems almost destined to have become a pan-American educator. A long, productive career spanning four decades as a teacher and consultant connects Gatún and Harvard. His work has focused on educational planning, institutions, and democracy. In 1997, the Organization of American States awarded the Andres Bello Inter-American Prize for education to McGinn, the first U.S. citizen to receive the award.

After receiving his Ph.D. in social psychology from the University of Michigan in the enthusiastic Kennedy-Peace Corps era, he took a job teaching for two years at the ITESO in Guadalajara, Mexico. Then he signed on for a project in the Dominican Republic called Education for Democracy. But it never materialized-the U.S. Marines invaded in 1965.

Instead, McGinn joined up with a team in Venezuela working to create a 20-year plan for Ciudad Guyana’s educational system. “The concept of educational planning was very new,” he says, laughing. “Of course, no one would ever think of doing something like that nowadays.” He comments that twenty years is too long to program ahead and plans need to be flexible.

But the experience was a valuable one. As a new field, educational planning had few practitioners but many clients, and institutions like the OECD and Harvard began to promote it strongly. McGinn began to work with a Harvard-based consulting group, a group of economists that incorporated professionals from other fields and eventually evolved into the Harvard Institute for International Development. For the next ten years, he worked as a consultant to foreign governments all over the world and later became installed as a teacher, researcher, and consultant in the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Education in Latin America

“People all over the world have gotten better educated over the last thirty years, although the problems have also gotten greater.” McGinn points out that notions of education are being profoundly affected by a change in the way we think about systems of planning, and decision-making in general. In the United States and abroad, there has been a shift over the years from a ‘bureaucratic’ to a more ‘democratic’ model of social organization, from hierarchy to hetararchy.

Unfortunately, education tends to be a backwards sector in the sense that it still follows a highly bureaucratic model in Latin America. This means that roles are strictly hierarchical, syllabi don’t change and are centrally derived, and there is little supervision of teachers, who often work in isolation. This bureaucratic model “separates thinking from doing” which allows power to accumulate and makes change difficult. This assembly-line approach tends to create poorly trained teachers who reproduce what they were taught. Overall, it is a paternalistic system where the children are not taught to make decisions.

Of course, there are good reasons why the bureaucratic model has been so enduring. “Democracy is not efficient, especially when resources are scarce,” says McGinn. He notes that there are dozens of interesting educational experiments in Latin America, but they tend to have localized impact. However, new sources of power have arisen in Latin American society. “The possibilities of improving the system are there now, and that’s good.”

In developed countries, McGinn says that teachers have more time to “think about things, read books and talk to each other”. The trend nowadays in developed countries is to understand teachers as “managers of the learning process.” This is a way of dealing with the increasing complexity and quantity of information in today’s world. The idea is to teach children how to learn on their own by navigating and interpreting sources of information, with the teacher as a resource. Such students will be capable of participating in team-based decision-making as adults.

“Every person builds their own knowledge,” continues McGinn. “Knowledge is interpreted fact, and the process of learning is a process of construction.” He goes on to say that the school environment should be a place to test out students’ understandings. “Teachers need to be experts in the construction process.”

Recent Work, Future Plans

“Good research has an effect, but over a long time and indirectly,” says McGinn. Much of his recent work has focused on the possibilities and limitations of applying educational research to policy. As he describes in the book Informed Dialogue: Using Research to Shape Educational Policy Around the World (co-written with Fernando Reimers, Praeger, 1997), this can be very difficult. During one experience in Pakistan, McGinn and Reimers presented their research and conclusions to an audience of policy-makers, who then proceeded to draft almost the opposite conclusions!

As a result, he has engaged in projects which aim to help people help themselves. He co-wrote another book for educational consultants called Framing Questions, Constructing Answers: Linking Research with Educational Policy for Developing Countries (co-authored with Allison Borden, Harvard University Press, 1995). “It is a ‘random pages’ book, meaning that you can open it up to any page and start reading.” It strives to get people to frame their own questions and go about answering them.

And the future?

“This is my last year of teaching,” he says. Lately, he has been spending quite a bit of time travelling with his wife Mary Lou. Together they have visited countries including Panama, Chile, and Argentina.

However, he will continue to be a formidable presence in the the field as he explores the links between democracy and education. He is the editor of a forthcoming book appropriately entitled Education and Democracy, which tackles such issues as decentralization and governance.

“Education has enormous implications for the democratization of societies,” explains McGinn, “because it constantly brings up the question of who’s going to exercise power.”

Spring 1999

André Leroux continues a life of learning through his thesis research on Mexican environmental policy. He is the assistant to the director of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies.

Related Articles

Editor’s Notes: Booknotes

On March 10, 1999, President Clinton apologized to the people of Guatemala for the support provided by the U.S. government to that country’s repressive military-backed governments…

Society and Education

As a member of UNESCO’s International Commission on Education for the Twenty-First Century, I’ve come to realize that education is about much more than books. It’s about the “four pillars of…

Latino Families and the Educational Dream

Insisting that we do our interview in English, Ricardo Robles reluctantly recalls the dreams he had for his children when first arriving nine years ago to the U.S. from Zacatecas, Mexico.” They…