About the Author

Nadia Milad Issa is a second-year Master of Theological Studies degree candidate pursuing the African and African American Religious Studies Area of Focus at the Harvard Divinity School. Nadia’s dance training and research centers post-revolution Cuba and the Regla de Ocha-Ifá/Lukumí spiritual-religious tradition and the Afro-Brazilian spiritual-religious traditions, Candomblé and Umbanda. Their ethnographic and dance-focused research, where Nadia spent over three years in Cuba and México pursuing fieldwork, is on Spiritual Reparations in Regla de Ocha-Ifá and other Black Diasporic Traditions and the politics of being an Akpwón in Cuba and its diaspora. Nadia is an Iyalochá (initiated high priestess) in the Ocha-Ifá practice. Nadia is a current Research Associate at The Pluralism Project, contributing their research experiences in Afro-Caribbean spiritual-religious traditions.

Oro a Egún

Yoruba and Diasporic Ancestor Relationships and Healing and Our Health

As I engage in spiritual ritual practices during the sacred celebrations of Fèt Gede from the Vodou spiritual-religious tradition as well as Día de los Muertos with origins in Aztec and Catholic traditions, I am grateful for the continuing relationship building that I engage in with Egún. Egún is the Yoruba word for “ancestors.” Egún in a slightly different Yoruba tone also means “bones.” This Yoruba word and its double meaning connect ancestors to the bones of the human body, emphasizing the interconnectedness between ancestors and living descendants. Egún are blood-related ancestors, as well as teachers, mentors, freedom fighters and revolutionaries. In the Afro-Cuban spiritual-religious tradition Regla de Ocha-Ifá (Lukumí), the Cuban version of the Yoruba spiritual-religious tradition from Nigeria, an Ocha-Ifá practitioner also inherits Egún through initiation, as one initiates, meaning one is spiritually rebirthed into that specific spiritual family network. During high school, I experienced the impact of losing family members. I wanted to find a way to best honor them, give them light and continue our relationships. Indigenous Yoruba ancestral practice is what grounded me in how to welcome their transition.

Egún are those who have transitioned into the Ancestor realm and enter Ancestorhood. My relationship with death and the dead is not definite nor signals an end of a life. Personally, instead of expressing that a loved one has died or passed away, I utilize language that is present and active. I say that a loved one has transitioned, this emphasizes how present and near in proximity ancestors truly are. Ancestorhood is a continuation of living, a transformation from personhood into Ancestorhood, emphasizes how the dead are not dead, and how death is not static, and that reincarnation follows in my Indigenous Yoruba cosmology. Cosmology refers to the notion of the universe, the notion of the ideas and nature of the Universe as constructed by people. Cosmologies tells us how a people are grounded and constituted in the world. Cosmologies tells us the practices, values and principals guide a community. The Yoruba cosmology takes spirit and ancestors very seriously. One entering Ancestorhood brings great power or Aché (Àṣẹ, Axé, Ashé, or Aché has multiple meanings including “gracias” [thanks], bendición [blessings], equivalent to “amen.”) Aché is energy, power and divine power. Aché is also sacred spiritual-religious materials and responsibility that ancestors gain by having to guide and protect living descendants in both intentional sacred spaces and in their daily lives. In Ocha-Ifá rituals, ceremonies, and initiations, Egún are regarded as one’s first line of defense and must be asked through divination if the descendant can proceed with the ritual, ceremony or initiation or not. Egún are located in various places— buried in cemeteries, in the ocean waters, in the pipes of kitchen sinks, and most closely, around the bodies of living descendants.

As Ocha-Ifá practitioners, from Egún we understand the woes of our health by healing them, and with the Orishas we mobilize through ritual, ceremonies, and initiations to directly and heal the woes of our own health. My spiritual-religious and spiritually led academic work is grounded in this practice of health and wellness. My work as a scholar-practitioner is focused on the spiritual and physical health and wellness of Black, Brown and Indigenous people and those who practice Afro-Diasporic traditions, particularly Afro-Brazilian Candomblé and Afro-Cuban Regla de Ocha-Ifá by tackling religious racism through what I coined “spiritual reparations.”

I am currently in collaborations with other healers and scholar and artist-practitioners that focus on ancestral trauma and wholeness, hxstorical trauma, collective trauma and collective posttraumatic growth for Black, Brown and Indigenous folx. The framework and health manifestations of hxstorical trauma is originally outlined by Dr. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart. Brave Heart is an indigenous mental health expert, social worker, and associate professor who developed the model of “historical trauma” for the Lakota indigenous peoples. Brave Heart defines historical trauma “as cumulative emotional and psychological wounding over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma.” Hxstorical [a gender-neutral term] trauma for the Black community is the focus of the work of Elder Atum Azzahir of the Cultural Wellness Institute. Collective trauma is the psychological reaction that is shared by a group of people who all experience the same event and Collective Posttraumatic Growth is defined “as benefits perceived in the community and society as a response to collective trauma experiences” (i.e., natural disasters).

In the work of unpacking, processing and healing trauma, ancestors are often forgotten. In Ocha-Ifá, priestesses and priests who are also mediums, those who have the divine ability to communicate with ancestors, spirits and Orishas (deities of Ocha-Ifá), recognize how one’s ancestors’ death can be the root cause of a living-descendant’s trauma and retriggering of trauma. We recognize trauma as intergenerational, as ancestral. Since Egún trauma situates themselves in the bodies of descendant, trauma is embedded into the human bodies.

Ancestral trauma happens for many reasons. It is trauma experienced and continuously experienced by one’s ancestors and by descendants still living. Ancestral trauma exists if an ancestor died violently by murder, suicide, fights or a tragic accident, or they were not able to fulfill their life’s mission or goals. Ancestors who have had a “bad death” are quite literally unsettled and understood as floating in the ether and confused. These unsettled ancestors provoke manifestations of ancestral trauma that shows up in descendants’ daily lives. Ancestral Trauma for the living looks like discord, material and human losses, insomnia, irritability, lack of personal hygiene, disarray in the home and loss of consciousness.

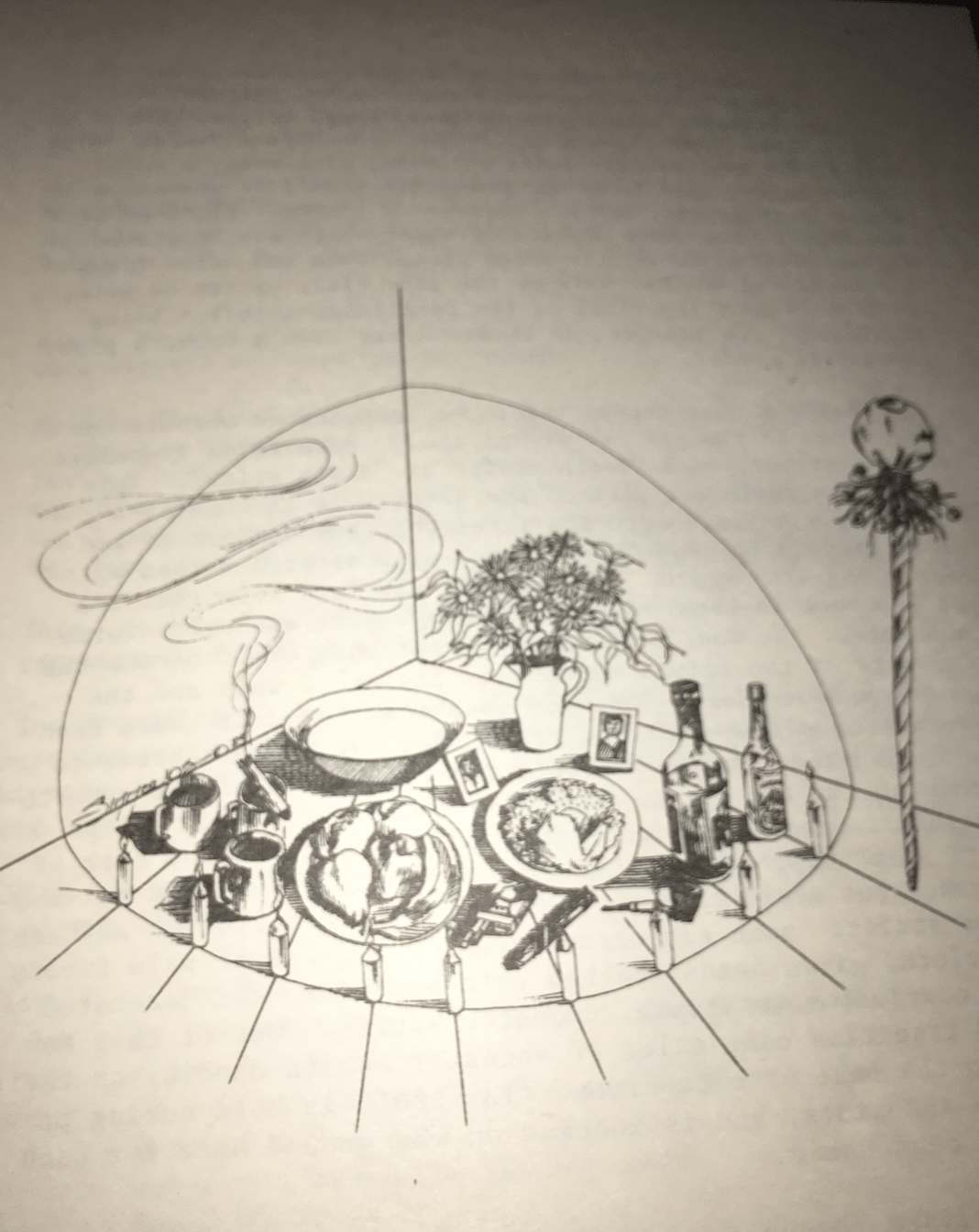

In order to heal ourselves, we must heal our ancestors first. In Ocha-Ifá we directly heal Egún, our ancestors through rituals and ceremonies such as rompimientos (breaking), limpiezas (spiritual cleansings) and the ceremonial ritual festive called El Cajón, where drumming, chanting and other ritual practices are central. Only through direct rituals and mass prayer, will ancestors heal and be able to settle. Through divination, Egún may request any specific ritual that they may need so that practitioners and descendants can settle their souls and they may transition in peace.

In the same chapter, Kalu cites celebrated Senegalese poet Birago Diop’s poem, The dead are not dead,

“Those who are dead are never gone:

they are there in the thickening shadow.

The dead are not under the earth:

they are in the tree that rustles,

they are in the wood that groans;

Those who are dead are never gone:

they are in the breast of the woman,

they are in the child who is wailing

and in the firebrand that flames.

The dead are not under the earth:

they are in the forest,

they are in the house.”

Here, I offer my poem, Oro a Egún, that I wrote in poetic response to Birago Diop, a Senegalese poet who is now an ancestor himself. My response amplifies Birago Diop’s poem through a Lukumí lens regarding ancestors, as Diop draws from Wolof traditions. I wrote this poem in collaboration with my ancestors and spirit guides who guide me.

Egún:

meaning, ancestors,

meaning, bones

Yoruba double meaning

to

locate our bones as dwellings

that do not just hold our flesh together in movement,

but,

as shared bodies that ties us

to collapsed temporalities

into

the multiverse world

of our defense line.

Egún:

Los Muertos están en la tubería de la cocina,

remember to pour out your altar water with a tender aché.

The corner of the room,

an electric candlelight,

a feast,

Efún of boundaries, balancing, and cooling

tap the palo con toda tu alma dentro del circulo.

Without Alafia of Egún

No hay nada.

Egún:

Copresences surrounded

seated

around our Ori,

shoulders

backs,

collarbones,

and spiritual mounting,

hugs us in heat,

por coronacion.

Egún:

in wine glasses of water,

in between our prayers and feet full of dance,

in between Bata, conga, cajon drum vibrations,

in the smoke del Espiritista,

in Ifa prayer versus del Babaláwo e Iyálawo.

Egún:

the ones we met,

the ones we didn’t get to

and ones we inherit

Agooooooooo

More Student Views

Puerto Rico’s Act 60: More Than Economics, a Human Rights Issue

For my senior research analysis project, I chose to examine Puerto Rico’s Act 60 policy. To gain a personal perspective on its impact, I interviewed Nyia Chusan, a Puerto Rican graduate student at Virginia Commonwealth University, who shared her experiences of how gentrification has changed her island:

Beyond Presence: Building Kichwa Community at Harvard

I recently had the pleasure of reuniting with Américo Mendoza-Mori, current assistant professor at St Olaf’s College, at my current institution and alma mater, the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Professor Mendoza-Mori, who was invited to Madison by the university’s Latin American, Caribbean, and Iberian Studies Program, shared how Indigenous languages and knowledges can reshape the ways universities teach, research and engage with communities, both local and abroad.

Of Salamanders and Spirits

I probably could’ve chosen a better day to visit the CIIDIR-IPN for the first time. It was the last week of September and the city had come to a full stop. Citizens barricaded the streets with tarps and plastic chairs, and protest banners covered the walls of the Edificio de Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca, all demanding fair wages for the state’s educators. It was my first (but certainly not my last) encounter with the fierce political activism that Oaxaca is known for.