A Review of Other Cities, Other Worlds: Urban Imaginaries in a Globalizing Age

Globalization in the Developing World

Other Cities, Other Worlds: Urban Imaginaries in a Globalizing Age By Andreas Huyssen Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2008.

Author of a marvelous book that excavates the palimpsests of memories encrypted in the image-filled voids of Berlin, Andreas Huyssen extends his investigation of the urban imaginary in this volume, which brings together twelve renowned authors’ reflections on the impact of globalization on cities in Latin America, Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

These cities have “their own very specific modernity distinct from the modernity of the Western metropolis” (14), in most cases because of their colonial legacies. The existence of analogous legacies does not entail that urban experiences or imaginaries are similar, for their insertion into European and North American circuits are different—e.g., British, French, Portuguese or Spanish colonial rule—as are their processes of decolonization and national consolidation. Different too is their insertion into current global processes: while Buenos Aires, one of the wealthiest countries in 1900, continues a half century of decline, Shanghai is poised to become the newest center of global command and control.

As Akbar Abbas writes in his chapter on the Asian city, globalization now requires the “acculturation of the commodity,” rather than the more common view that culture is commodified (259). He refers to the cultural and creative process, such as design and information programmed into commodities. Similarly, cities are branded or imagineered as part of the strategy to compete in the global market of advanced services. Bilbao put culture at the center of its revitalization plan, and creative city boosters like Richard Florida tell us that culture is a major attractor of creative talent, which in an age of increasing valuation (and policing) of intellectual property rights, is the most important contributor to economic growth.

Architecture and other components of the built urban environment play a major role, evident in each succeeding European Capital of Culture that recruits renowned starchitects to brand them. One of the most recent schemes, the Universal Forum of Cultures (2004), invented by the Catalonians as a new world event congruent with the information and knowledge society of the global era, and which was a controversial gambit to regenerate Barcelona, is now circulating like the Olympics. Its second edition was held in Monterrey (2007) and its third was vied for by Alexandria, Amsterdam, Budapest, Chicago, Durban, Fukuoka, Gwangju, Santiago, Suwon, and Valparaíso, which was selected.

Okwui Enwezor analyzes a similar process of circulation of biennales and mega-exhibitions, which seem to multiply like mushrooms, and which some critics celebrate as a “decentering of the West” (155). While he acknowledges that these circuits provide an opportunity for “artists hoping to leap outside under-funded contexts and into the resource-rich pastures of the global space” (157), thus reinforcing the artistic field, Enwezor rejects the view that postcolonial artists merely mimic Western forms. Instead, the postcolonial response springs from an “ethics of dissent” that enables historical transformation “and…is able to expose some of the Western epistemological limits and contradictions” (167). He further identifies this dissent with “postcolonial subjective claims (multiculturalism, liberation theology, resistance art, feminist and queer theory…) [that] deviate from the hegemonic concept of spectatorial totality and render it fragmentary” (172).

Enwezor associates this new spectatorship with De Certeau’s notion of everyday users, who instrumentalize their agency in diasporic public spheres, where the translation of culture takes place. As such, the organization of biennales in the periphery does not constitute mimicry but points to “the possibility of a paradigm shift in which spectators are able to encounter many experimental cultures without wholly possessing them” (170). But Akbar Abbas’ lucid observation that artistry is part of the global cultural commodity gives a different spin to the new paradigm of spectatorship. He finds a parallel process of inclusion celebrated by Ziauddin Sardar to be overly optimistic– “Malay bodies clad in fake designer jeans…are in-cluded, fashion and fancy, and not ex-cluded, marginalized onlookers. In the international politics of self and style they are fully empowered” (260). Moreover, Abbas argues that in the spatial logic specific to the information age, Castells space of flows, the circuitry of networking permits centralization and decentralization, such that command remains in cities like New York and London, while back offices are located in peripheries that form part of the network. These circuits can be grassrooted, but it takes a long time for that to make a difference; hence uneven development in the global era.

Abbas’ “Faking Globalization” is more than about the fake; it is about new spatialities in Asian cities. The above-mentioned uneven development of the global era is manifest in the X-urban or pairing of urban and suburban, which circumvents the ring of poor neighborhoods and factories that envelop the urban core. What is new in this spatiality is not the spectacular architecture that sprouts in the business centers of the suburbs, but the process of replication, which is not, according to Abbas, Westernization (249). The fake breathes a new life, so to speak, in this spatiality, which marks the threshold where it can transform…into what? Abbas observes astutely that makers of genuine articles make recourse to faking in their own production processes. Nevertheless, they clamor for intellectual property laws that are hypocritical. The best way, then, “to go beyond the fake is not through legislation, but to encourage the development of design culture” (263). But it is not clear what the value of transformed objects will be if there isn’t a hypocritical intellectual property law that assigns it. Abbas writes, “Once [China] can design, it will be unstoppable” (263). Will it join the US and Europe in upholding intellectual property?

In this book, Asian cities are the only ones capable of joining Western metropolises as centers of command and control. Sarlo’s Buenos Aires, Caldeira’s São Paulo, García Canclini’s Mexico, Judin’s Johannesburg, Prakash’s and Mehrotra’s Mumbai, and Ghannam’s Cairo are all characterized by an uneven development that will not easily flip into “unstoppability.” In all of them, the same process of X-urbanization takes place, but the fragmentation prevails, as the state retreats, public space is privatized or terrorized by crime, informality in the form of street vendors, migrants and squatters leech through the formal city, and even “nature find[s] its way through the crevices” (Judin, 122). One can discern a variation in the affect of each author. For Sarlo, the double whammy of Losangelization and Latinamericanization of Buenos Aires, once Queen of the Rio de la Plata, seems to elicit frustration, perhaps even a resigned outrage. Caldeira’s disjunctive democracy, failed modernization, civil society lapsed into fear and an aesthetics of security spatialized in the X-urban walling off informality, is barely offset by the hope that the institutions built in better times will receive a shot in the arm to assuage the inequality (75), probably the most acute in Latin America. García Canclini holds out a bit more hope in the partial democratization of Mexico City, and he also banks on a media policy that resonates with the majority and contributes to the construction of an intercultural public culture. In the heyday of modernization and the golden age of Mexican cinema, the movies helped Mexicans learn how to be modern, Carlos Monsiváis has written. Now, however, the media, festivals and public events need to establish intercultural relations, particularly in this megalopolis of nearly 20 million in which neighborhoods are so distant from each other, and traffic so congested that residents’ paths will never cross. But inequality remains a sticking point (95).

For Mehrotra, Mumbai is characterized by a pirate modernity in which a formal-static city and an informal-kinetic one are most often at cross-purposes. Architecture is the mode of spatialization of the first; motion and the space of the everyday, that of the second. Mehrotra discerns, however, instances of reconciliation that may enable the city to cope with its dualism. For example, arcades can maintain the illusion of architectural integrity while they provide a place for the hawkers of the kinetic city. The “disciplined Victorian arcade…could contain the amorphous bazaar within” (213). Likewise, festivals, which enable the articulation of subalterns’ fantasies, can be accommodated in formal architectural spaces. Solutions like these have been tried in cities like Bogotá and Medellín, which would have been excellent points of comparison, for they have been quite successful in diminishing fragmentation through architecture as well as accommodating the kinetic city through events. In both cases, plural and vibrant citizen movements and cooperative municipal governments gave a more formal shape to the negotiated solutions proposed by Mehrotra.

Other Cities, Other Worlds is filled with so many insights that could not be mentioned in such a short review. Aside from the essays themselves, what I most appreciate are the resonances, wherein one essay echoes or responds to another. Together, the chapters deal with a range of scales, images, actors, forces and affects. I conclude with two of the latter. Simone’s resolute defense of the practices of everyday life whereby actors in Middle African cities continually reconvert commodities. It is the kinetic city writ large, in which the process of conversion resolves, as Cubans say, that for which there are no resources. Orhan Pamuk’s eloquent anatomy of hüzün or collective spiritual loss that suffuses Istanbul, or as he writes, is “spread like a film over its people and its landscapes” (299). Pamuk distinguishes it from the more individual melancholy and nostalgia or the external observer’s tristesse. Tellingly, it is an emotion absent in all the other contributions, even those that dwell on “everyday actors,” perhaps because, as Simone remarks, there is an unpredictability to acts of “making do” that foreclose conviviality, an essential feature of hüzün that for Pamuk gives poetic license to a dignified resignation. That is a poignant observation on global imaginaries.

Spring 2009, Volume VIII, Number 3

George Yúdice teaches Latin Americal Studies at the University of Miami. He is the author of The Expediency of Culture: Uses of Culture in the Global Era (Durham: Duke UP, 2003) and Nuevas tecnologías, música y experiencia (Barcelona: Gedisa, 2007).

Related Articles

A Review of Llamas beyond the Andes: Untold Histories of Camelids in the Modern World

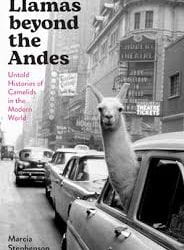

Marcia Stephenson’s Llamas beyond the Andes is about humans making use of another animal. With a dustjacket image of Llinda Llee Llama riding in the back of an automobile in mid-20th-century Times Square, this book illustrates how sentient nature has been engulfed by human cultural objectives since Columbus’ arrival in the Americas and the rise of Europe’s global imperial ventures. The window on all this is American camelids: llamas, alpacas and their wild relations, guanacos and vicuñas.

A Review of Born in Blood and Fire

The fourth edition of Born in Blood and Fire is a concise yet comprehensive account of the intriguing history of Latin America and will be followed this year by a fifth edition.

A Review of El populismo en América Latina. La pieza que falta para comprender un fenómeno global

In 1946, during a campaign event in Argentina, then-candidate for president Juan Domingo Perón formulated a slogan, “Braden or Perón,” with which he could effectively discredit his opponents and position himself as a defender of national dignity against a foreign power.