Paid Domestic Workers, Women and Democracy

When Do We All Move Upstairs?

Photos By: Daniela Ortiz

I first visited Peru in 1995 as a graduate student and junior member of a Latin American Studies Association delegation to examine the state of democracy in that country on the eve of its presidential elections. Despite having staged a self-coup three years earlier, then-president Alberto Fujimori was favored to win. He did, and I would end up living in Lima little more than a decade later, thereby witnessing directly the results of his cooption of key institutions including the news media, civil society organizations, the judiciary, other key regulatory agencies and the armed forces. Predating Fujimori´s pulverizing dictatorship, however, the sources of Peru´s democratic frailty remained ever-present and resilient.

As a new resident it did not take long to register that the tacit social contract was less about constructing a society of political equals with rights and responsibilities, and more about establishing a hierarchy of those who can access and purchase quality goods and services in a highly informal market. In this case, the term “citizen” meant little to most of the country´s 30 million residents. A more apt term might be consumers; some with the means for consumption. And others, simply consumed.

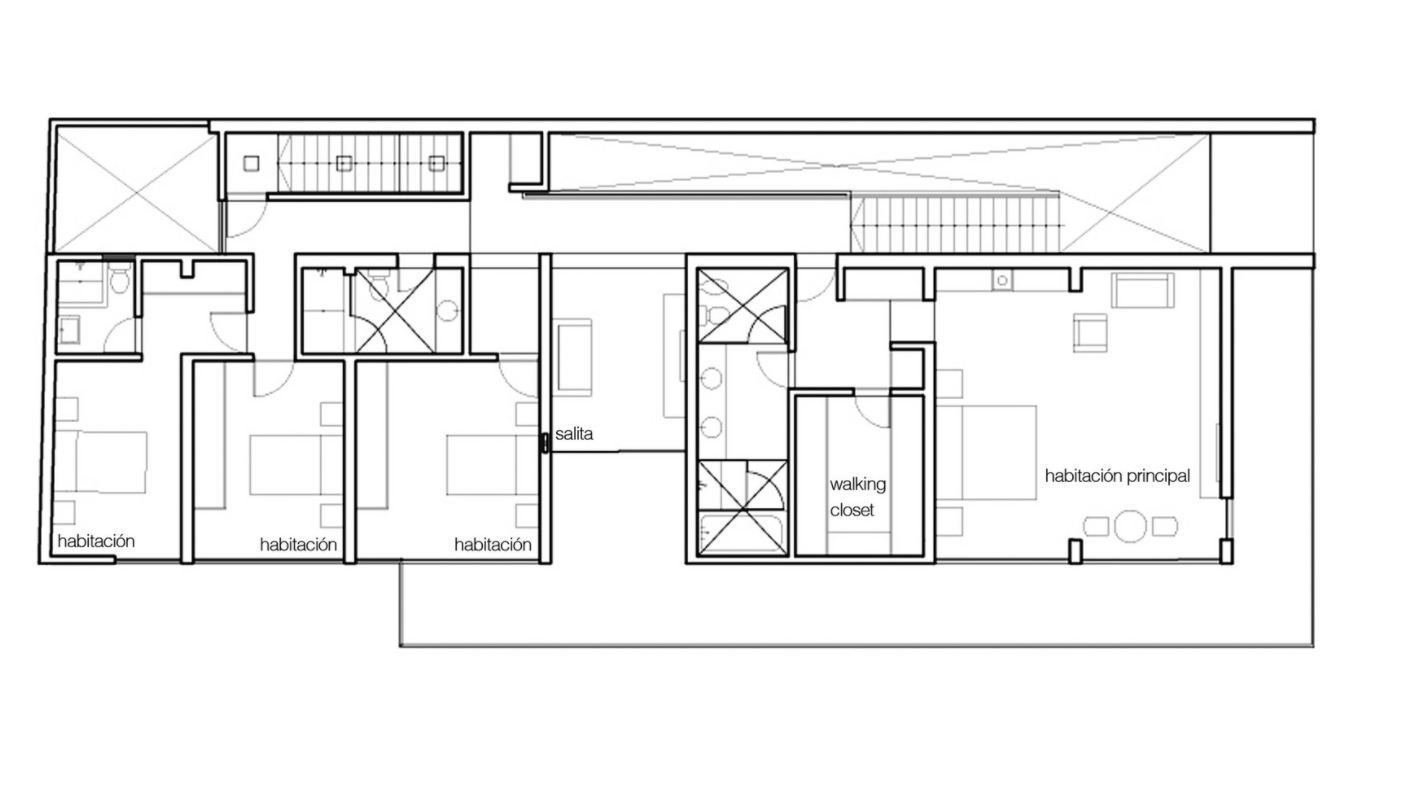

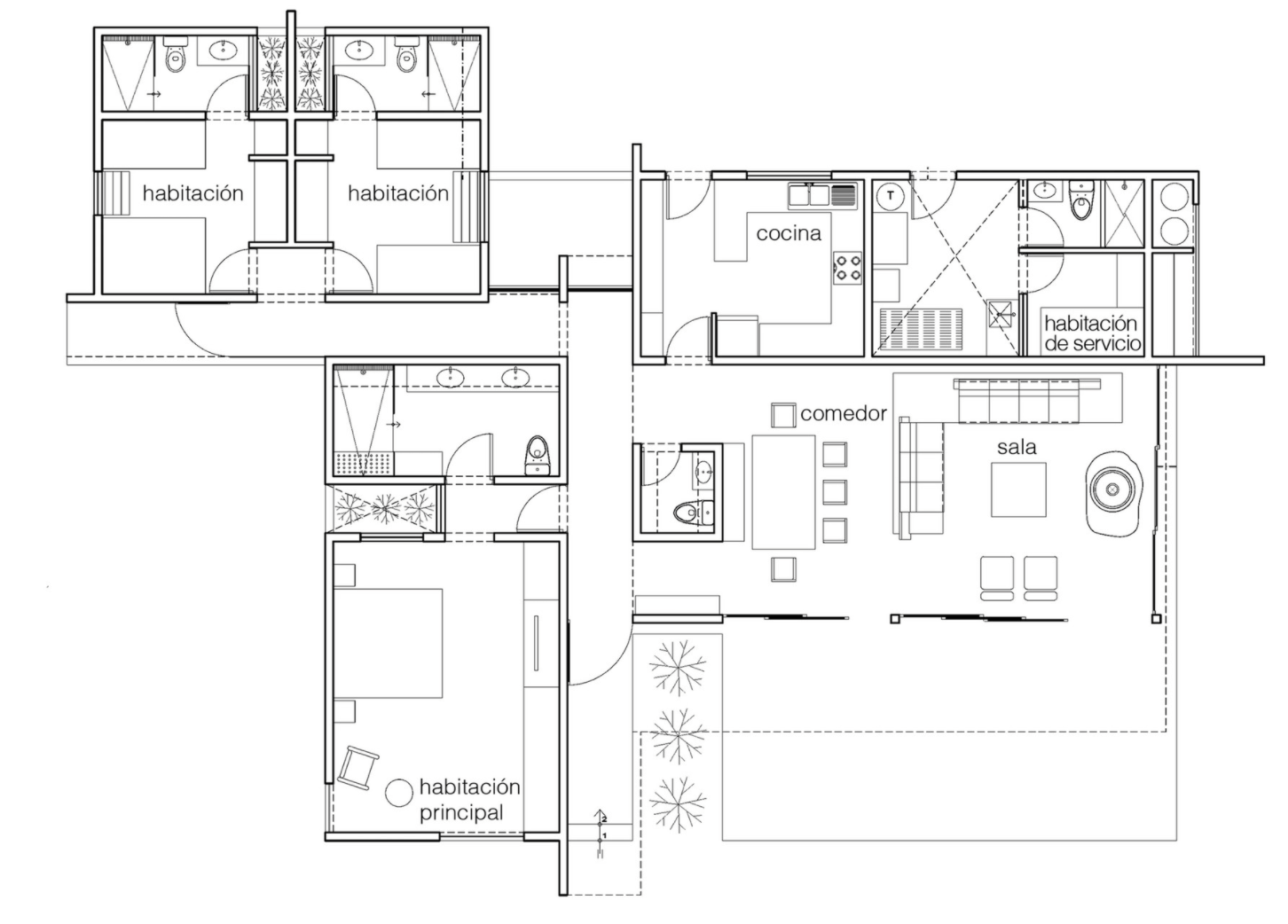

One early, stark discovery about the societal division, or hierarchization, was the puerta falsa (back door) in the construction of apartments in Metropolitan Lima. This was the threshold through which the country´s army of domestic workers might enter a residence. This doorway led directly to the laundry room, kitchen and a closet masquerading as a bedroom for those workers who “lived-in,” cama adentro, with their employers. I would find, too, that this arrangement did not only exist in “old” buildings like mine, built in 1968, but that these same construction parameters continued well into the aughts of the new century. These workers were, both in the law and de facto, second-class denizens.

Location: La Molina – Lima, Peru. 2010

Mostly female migrants, they are highly vulnerable due to the confluence of their gender and origins, oftentimes having low educational attainment and pertaining to ethnic minorities. Domestic workers are still a fixture in the modern world, yet are mostly rendered invisible in the private homes of their employers. Latin America, following the Middle East, is the region with the second largest workforce. More than one out of every four female wage workers work as maids. It is a job that is woefully underpaid – sometimes not paid at all – discriminated and marginalized. As opposed to the “upstairs, downstairs” theme of this magazine´s present issue, based on the European model of male and female household workers in the service of the upper classes, domestic service today offers little—if any—upward labor mobility as did last century´s system in the old continent. In most of the world, certainly in Latin America, it remains a dead-end job for the mostly women and—still too often—girls who do it.

My research has led me into some of Lima´s achingly poor, urban shantytowns, as well as to Peru´s remote and impoverished highlands. Years of study in this country, including myriad interviews with workers, confirm the precarious—often, servile— social and labor positioning of the women who do this work, including tight control over their movements, overall discrimination and sometimes—too often for my taste—the branding of their bodies through uniforms or distinctive clothing, which emphasizes that they are considered inferior. Most recently, together with other researchers, we are examining the evolution of the socio-political rights of domestic workers in three South American capital cities: La Paz (Bolivia), Lima (Peru), and Montevideo (Uruguay).

In a global context in which the International Labor Organization (ILO) set forth the Domestic Workers Convention (No. 189), approved in 2011, with Latin America providing the highest number of ratifications in the world, we ask, how do we—might we—value domestic support and human care? What do the laws accomplish for the rights of these workers? Likewise, following decades of organizing and the noteworthy leadership of domestic worker unions, what have these activities done for their attainment of equal sociopolitical status, resembling that of a full citizen?

First, the good news. Convention 189 would have never succeeded had it not been for international domestic worker organizing and the ILO´s commitment to the norm. To name only a few countries, Uruguay was the first in the world to ratify the Convention in 2011, with Bolivia following suit shortly thereafter in 2013, and Chile in 2015. Peru ratified the Convention seven years later in 2018. The results, however, have been mixed.

Uruguay not only ratified ILO 189, but launched its own National Care System, —focused on the provision of universal care services, while promoting and ensuring care worker rights. Bolivia, by contrast, also ratified the Convention, but did little else to advance full inclusion, despite naming a former domestic worker to head the Ministry of Justice. Chile registered workers, making their hiring and dismissal more transparent, and has most recently named a former domestic worker and union leader as subsecretary of the Ministry for Women and Gender Equality. Peru took its time in approving the Convention—a combination of little support from the legislative branch, differences among domestic worker unions, and a wider population generally unconcerned with whether these workers have access to decent pay and social protections.

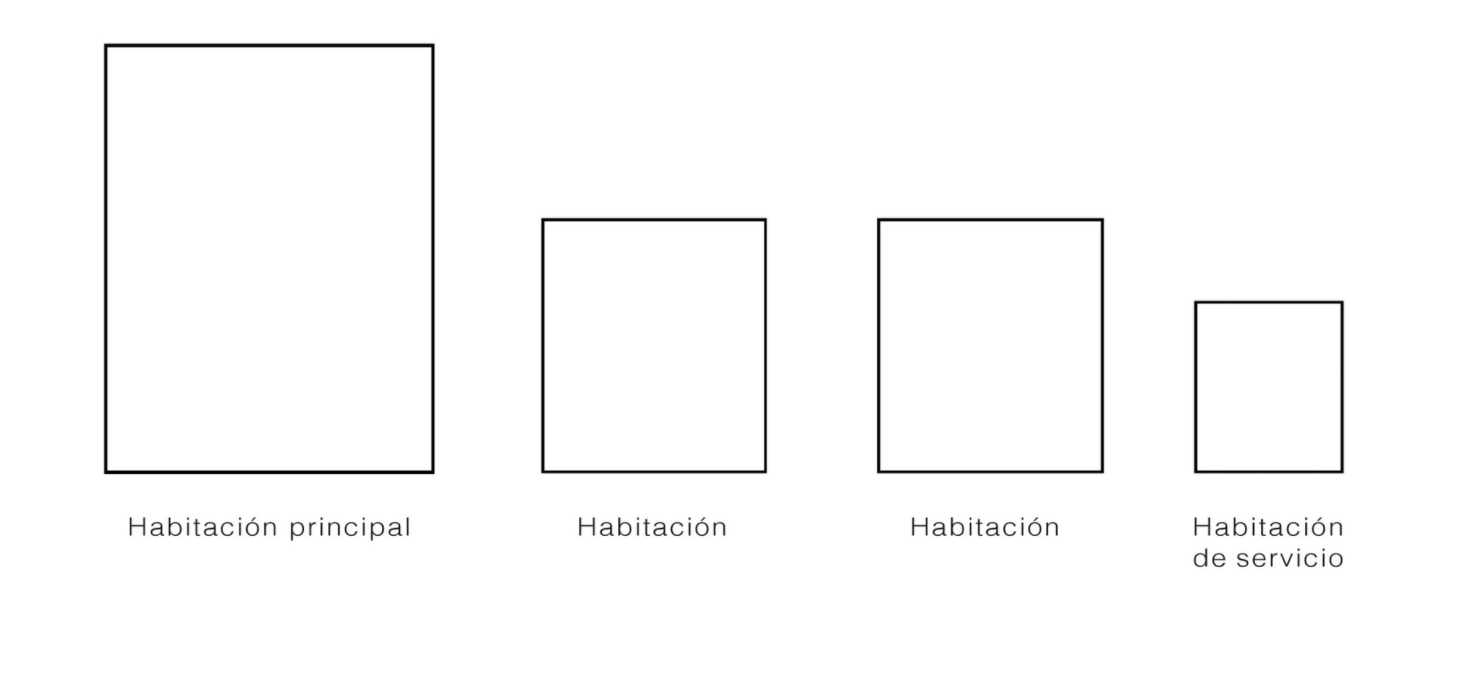

The room of a domestic worker [top-left; habitación de servicio], with an area of 3.8 meters squared.

But, since we´re on the “good news,” here it is for Peru: in 2020, through the arduous and tenacious work of domestic worker unions, a new law was finally approved. In this case, it meets the expectations of Convention 189 including, a minimum wage, overpay for hours worked, written contracts registered with the Ministry of Labor, subsidized health insurance and a ban on child labor, to name only a few of the stipulations. This is an undeniable win for this sector, underscoring the value of its work—cooking, cleaning, washing, ironing, caring for children and/or dependent adults; moreover, managing households, including children´s schedules, caring for pets and plants! Thus, the new law makes visible those doing the domestic work that enables household residents—and, let´s face it, particularly women—to step out to work and engage in diverse social activities.

The bad news is that old habits die hard, and the reality for domestic workers around the world is that discriminations persist. A 2014 article by Finnish researcher Merita Jokela correlates the national presence of domestic workers and high levels of economic and social inequality. This finding powerfully underscores that paid domestic workers are a barometer for not only country-level inequality, but women´s positioning in these contexts – either as looked-down-upon providers of socially and economically demeaned household and care services, or as purchasers of this support from an underclass of “othered” women. In either case, it speaks volumes to the continued barriers and challenges faced by women in attaining equal status in our presumed democracies. They are either the exploited group that provides necessary social reproduction services, or they are part of the exploiting establishment, securing a place of supposed equality through a Faustian bargain that sacrifices some for the benefit of those who have other options in education and work. Ultimately, it´s a woman who is shouldering the burden in the doing, or in the managing, of work that is tenaciously unrecognized and, thus, unvalued.

Despite important legislative wins across Latin America, all of the domestic workers I have interviewed over the years have experienced varying degrees of exploitation and discrimination. Due to the persistence of a server class legacy, lax enforcement of universal legal rights and high levels of labor informality in which work precarity is the norm for most, there are some who consume— products, natural resources, public spaces, rights and services—and there are those who provide those products, resources, or services with little social recognition or political insurance of their rights.

In Peru, for example, despite efforts toward reclaiming the public space for all through amplified access to parks and ubiquitous signposts that declare zero tolerance for discrimination, middle- and upper-class recreation areas are still replete with uniformed, migrant women of color caring for others´ children. Or there are beach towns where residents and guests meander carefree, as apron-clad domestic workers cook the food and care for the children. I should not be misunderstood here. Food needs cooking and children need caring, and both are necessary and important activities. The heart of the problem is that the women who provide these critical services are met with disdain and marginalization, revealing a particular social polarization in which some are kept, much like Cinderella, clothed in soot, as it were, relegated to the hearth, and barred from joining the larger social Ball.

This situation has been most poignant during the pandemic. Recent scholarship in Latin America has shown that workers have been sent home without pay or access to social protection. Due to strict social distancing and lockdown measures, some employers have insisted that workers remain, or shift to, cama adentro to paralyze their mobility, presumably limiting the spread of the virus. But it has also meant that they have been exposed to illness with no support, even in cases where employers – not them – were infected and forced workers to live-in, rather than forgo services. There have been lives lost. My own research in Peru with Andrea Gandolfi, Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at Lima´s PUCP has found during the pandemic that more than four out of every five domestic workers were fired indefinitely with no government bonus or hardship pay either from their employers or the state.

The bottom line is that the best-written laws in the world won´t change societal attitudes regarding a significant part of the workforce. Uruguay´s efforts to reconfigure the notion of care as one that must be revalued, redistributed and reformed is a model for emulation. But this was also possible because of its of democratic institutions, including inclusive labor laws and formidable unions. For Bolivia, the rights of these workers are not uniformly enforced; in Peru, it is still unclear how—or whether—the full extent of the law will be enacted and monitored by the state.

A domestic worker’s room [top-right; habitación de servicio] with an area of 4 square meters. Location: Cieneguilla in Lima, Perú, 2011.

[From left to right] Master bedroom, bedroom, bedroom, domestic worker bedroom.

Shortly after moving to Peru, and following many conversations about the disparaging treatment of domestic workers, I was invariably referred to Peruvian writer Alfredo Bryce Echeníque´s classic, Un Mundo Para Julius, a tale of Lima´s 1950s high-class society, contrasted against its domestic staff. I never could finish reading that book because of my frustration about what I saw around me regularly—in 2006, the differentiated existence of the workers I saw daily did not seem to have progressed markedly in comparison to that described in the book. In 2021, my research team and I still gathered testimony about sexual harassment—in too many cases, rape—in some of the workers´ early experiences, not unlike that described in Bryce´s novel.

Simply put, domestic work portends profound implications for democracy. What does it mean that the service that allows for others to go about their daily business, ensure the hygiene of homes, the care of children and dependent adults, and the overall ability to enjoy life, rests on the shoulders of an underclass of women? The “back door” is, by design, a vessel through which some people´s tangible, foundational support enters and exists unnoticed, unaccounted for, and undervalued. Seen in this light, it is unsurprising that the region´s democracies remain unconsolidated, as half of our citizens are either relegated to the margins, or saddled with managing work that remains squarely on the backs of women.

There is indeed a ray of hope in the crafting of new laws that recognize this labor and the people who provide it as social and political equals. But, unless they are actively seen and included in the citizenry—and this means that the state must promote their value and ensure that their rights are met by their employers who, in turn, view these workers as co-citizens – I fear that my country of residence, as many others in the region and beyond, will remain as a cracked mirror image of democracy. There can´t be full democracy as long as some women remain “downstairs,” and others employ them as part of a larger societal power-sharing charade.

Leda M. Pérez is a professor with the Department of Social and Political Science at the Universidad del Pacífico in Lima, Peru. Her research engages with how the intersectionality of different conditions collude to position women socially and at work.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter

Editor's Letter Upstairs, Downstairs (and In-Between)When Argentine biologist Otto Solbrig was interim DRCLAS faculty director many years ago, he commented more than once that ReVista did not feature enough photos of middle-class people. I tried to respond to his...

Invisible Commutes

English + Español

Belén García, a Colombian domestic worker, wakes up at five in the morning every day in her home in the chilly mountains of southeastern Bogotá. After taking a shower, she dresses in several…

Slavery Upstairs, Slavery Downstairs

On February 14, 1800, someone slipped an anonymous letter to the solicitor general of Lima’s high court via one of his domestic servants. When he opened it, the solicitor (fiscal)…