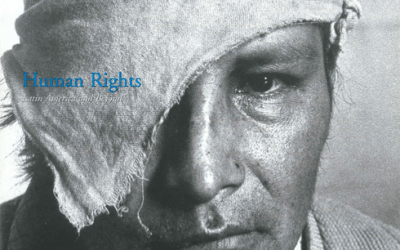

Peruvian Commission on Truth and Reconciliation

Presentation of the Final Report: A Photoessay

Today Peru is confronting a time of national shame. The two final decades of the 20th century are—it’s necessary to say without beating around the bush—a mark of horror and dishonor for the Peruvian State and society.

When the Commission on Truth and Reconciliation was set up two years ago, we were given a vast and difficult task: to investigate and make public the truth about two decades of political origin that began in Peru in 1980. As we finish our labor, we would like to present this truth with a fact that—although it is overwhelming—is at the same time insufficient to understand the magnitude of the tragedy experienced in our country. The Commission has determined that the number of fatal victims in the last 20 years most likely exceeded 69,000 Peruvian men and women, dead or disappeared at the hands of subversive organizations or State agents.

This figure, a statistic that seems ridiculously high even as I speak it, is one of the truths with which Peru today is going to have to learn to live if it truly wishes to become what it proposed when it became a Republic. That is, a country of human beings equal in dignity, in which the death of each citizen counts as its own misfortune, and in which each human loss from an attack, crime or abuse puts into motion the wheels of justice to compensate for the loss and to punish those responsible.

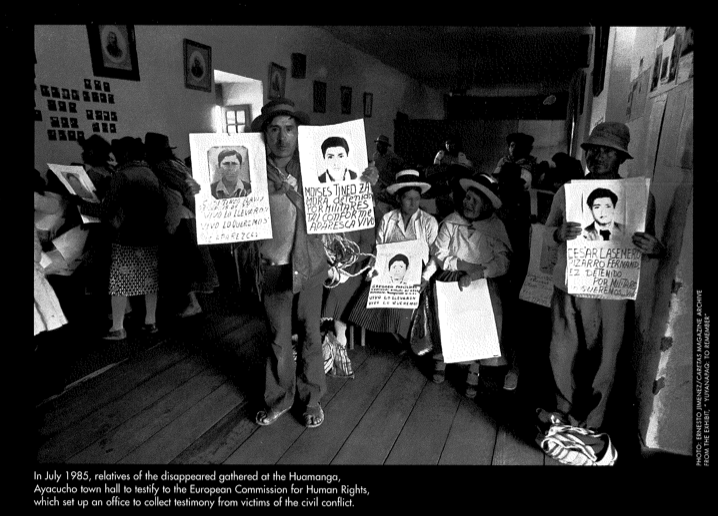

During the two decades of violence we were called upon to investigate, there were neither justice nor restitution nor sanctions. Even worse the memory of what occurred has never even existed. That leads us to believe that we are still living in a country in which exclusion is so absolute that it is possible for tens of thousands of citizens to disappear without anyone in the integrated society—the society of the non-excluded—even noticing.

Effectively, we Peruvians tend to say, in our worst previous case scenarios, that the violence left 35,000 lives lost. What does it say about our political community, now that we know that 35,000 more of our brothers and sisters are missing that no one missed then?

A DOUBLE SCANDAL

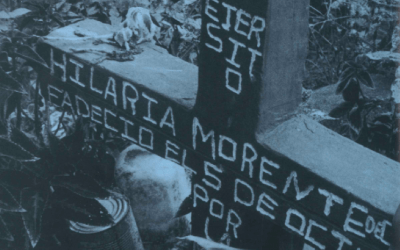

We have had to document, year after year, the names of dozens of Peruvians who once existed, who ought to exist now and yet are no longer. And the list that we hand over to the nation today is much too long for Peru to keep talking about errors or excesses by those who participated directly in these crimes. And the truth that we have found is also too sweeping for any government authority or ordinary citizen to claim ignorance as a defense.

The report we hand over today, therefore, is a double scandal. To a large degree, it is the scandal of murders, disappearances and torture. It is also a scandal about the ineptitude, slackness and indifference of those who could have stopped this humanitarian catastrophe and didn’t.

In this report, we faithfully carry out the task we were given, as well as the task we set for ourselves to publicly expose the tragedy as the work of human beings being made to suffer by other human beings. Of every four victims of the violence, three were peasants whose native tongue was Quechua, a large segment of the population that has generally been overlooked—and on occasions disdained—by the State and by the urban society that does enjoy of the benefits of a political community.

Racial insult—verbal aggression against dispossessed persons—rings out like an abominable chorus preceding a blow, a son or daughter’s kidnapping, a point-blank gunshot. One gets angry listening to strategic explanations for why this was indicated as a byproduct of war to wipe out this or that peasant community or to subject entire ethnic groups to slavery and forced displacement under threat of death. Much has been written about the cultural, social and economic displacement persisting in Peruvian society. Neither State authorities nor citizens have done much to combat such a stigma on our community.

Concrete responsibility must be established and made public; the country and the State cannot permit impunity. We have found much proof and indications that point in the direction of those responsible for serious crimes and, respecting the proper procedures, we will turn our findings over to the appropriate institutions so they can carry out the law. The Commission on Truth and Reconciliation demands and encourages Peruvian society as a whole to accompany it in this demand that criminal justice system act immediately, without a spirit of revenge, but in an energetic way and without any hesitation.

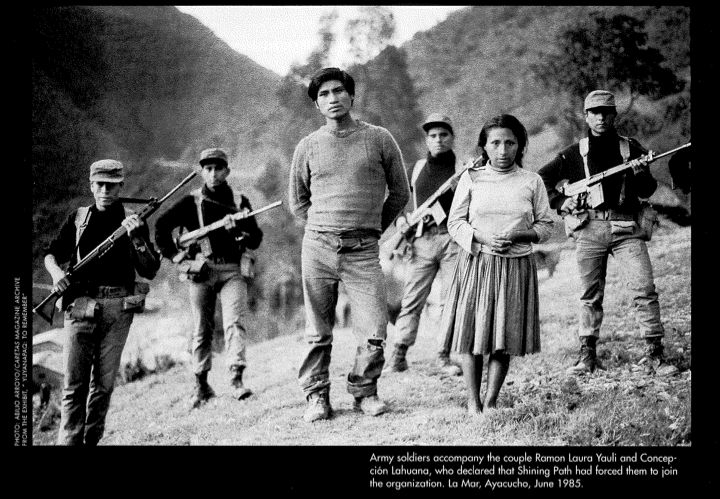

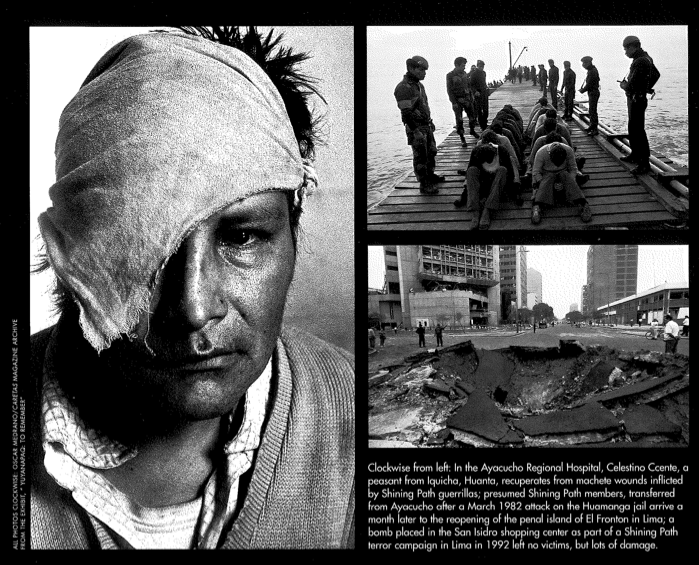

However, there is something deeper here than accessing individual responsibilities. We have found that the crimes committed against the Peruvian population disgracefully were not isolated acts attributable to isolated perverse individuals who transgressed the norms of their organizations. Rather, our field research with testimonies from 17,000 victims has allowed us to categorically denounce the massive perpetration of crimes, in many cases coordinated or planned by the organizations or institutions taking part directly in the conflict. In these pages, we show the manner in which the annihilation of communities or the devastation of certain villages were systematically anticipated in the strategy of the so-called “Communist Party of Peru—Shining Path.” The invocation of “strategic reasons,” which camouflaged the will for destruction above all basic rights, was a death sentence for thousands of Peruvian citizens. Such a will towards death embedded in the Shining Path doctrine cannot be distinguished from its essence as a movement in these twenty years. The sinister logic spelled out without evasion in the declarations of the representatives of this organization was ratified in their willingness to inflict death through the most extreme cruelty in order to achieve their objectives of bloody revolution.

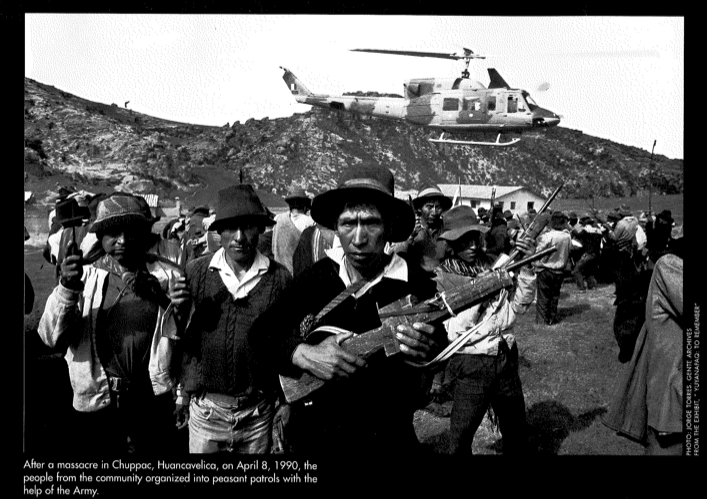

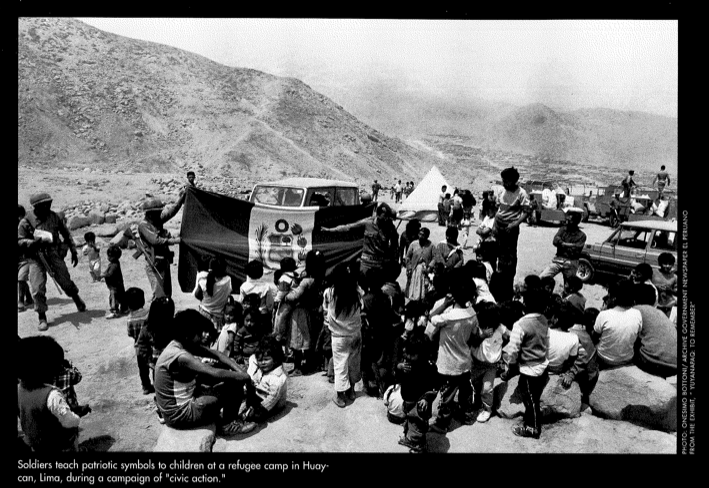

There was an enormous challenge, and it was the obligation of the State and its agents to defend the life and integrity of the population with legal arms. Democratic peoples support and demand order, based on their constitution and legal institutions, but that order can only be one that guarantees the right to life and respect for personal integrity. Disgracefully, within the struggle that the State and its agents did not initiate and whose justification was the defense of the society that was under attack, those in charge of this mission sometimes did not understand their obligations.

Keeping in mind the norms of international law that regulate the civilized life of nations and the norms of a just war, we have sorrowfully concluded that agents of the Armed Forces and the Police participated in the systematic or generalized practice of human rights abuses and therefore grounds exist to point out the commission of crimes against humanity. Extrajudicial executions, disappearances, massacres, torture, sexual violence, directed principally against women, and other equally condemnable crimes—because of their repeated and widespread nature—make up a systematic pattern of human rights violations that the Peruvian State and its agents must admit and rectify.

So much death and suffering cannot take place and escalate just because of some mechanical action by some members of an institution or an organization. It needs the complicity, the consent or, at the very least, the willful blindness of those who had the authority and therefore the capacity to prevent these actions. The political class that governed or had some quota of official power in those years have to do a lot of serious explaining to Peru. The people who asked for the votes of the citizens to have the honor of leading our State and our democracy and who took an oath to enforce the Constitution chose too easily to surrender to the Armed Forces those powers the Nation had vested in them as elected officials.

The armed struggle unleashed in our country by the subversive forces bit by bit involved all sectors and institutions of the society, causing terrible injustice and leaving in its wake death and desolation. Faced with this situation, the nation has known how to react with firmness, although tardily—interpreting the sign of the times as an opportune moment to make a conscientious examination about the meaning and causes of those events. We have made the decision not to forget, to recuperate memory, to try to find the truth. This time of national shame must also be interpreted as a time for truth.

We have sought to commit the entire nation to the activities of listening to and investigating what happened in Peru so that the truth will be recognized among all of us Peruvians.

At the same time we must negate oblivion, pulling away from the culture of covering things up. To bring to light that which has lurked in the shadows and to recuperate memory are different ways of referring to the same thing.

The transgression of the social order through war and violence is precisely the excess that forgets the essential, that hides the essence of our nature as human beings. Truth that is memory can only be fully realized in the carrying out of justice.

Because of this, this time of shame and of truth is also a time of justice.

WHO IS RESPONSIBLE?

In the strict sense of the penal code, the responsibility falls on those who directly cause the crime, on its instigators and accomplices and, above all, on those who—having the power to prevent the crime—evaded their responsibility. They will all, then, be identified, put on trial and sentenced according to the law. The Commission on Truth and Reconciliation has compiled for this purpose materials and files on specific cases, and will turn over this information to the judicial officials of this country so that they may act in accordance with the law. But in a deeper sense, precisely in the moral sense, the responsibility falls on all those people who through action or omission, for their position within the society, did not know how to do what was necessary to impede the tragedy that was being produced nor did they stop the tragedy from reaching such magnitude. On their shoulders falls the burden of a moral debt that cannot be shaken off.

Now then, ethical responsibility is not restricted to our relationship with the acts of the past. For the country’s future, that future of harmony to which we aspire, in which violence is brought to an end and more democratic relations reign among Peruvians, we all share responsibility. The justice that is demanded is not only of a legal nature. It is also a demand for a more rewarding life in the future, a promise of equity and solidarity, precisely because it is rooted in the feeling and conviction that we did not do what we should have at the hour of the tragedy.

The hour has come to reflect on the responsibility that is incumbent on all of us. It is a moment to commit ourselves to the defense of the absolute value of human life and to express with actions our solidarity with those Peruvians who have been unjustly treated. In that manner, our time is one of shame, of truth and of justice, but also one of reconciliation.

There is no doubt that the central question for the rethinking of the national memory is to link it closely with the question of future reconciliation. In order to truly take advantage of this opportunity to imagine the ethical transformation of society, many conditions will have to be fulfilled. The Final Report that we present now wishes to be the first step in that direction.

We live difficult and painful times in this country, but they are also equally promising times, times of change that represent an immense challenge to the wisdom and freedom of all Peruvians. It is a time of national shame in which we ought to shudder deeply as we become aware of the magnitude of the tragedy lived by so many of our fellow countrymen and women. It is a time of truth, in which we must confront ourselves with the crude history of crime that we have lived in the last decades and we also ought to become conscious of the moral significance of the effort to recall what was lived through. It is a time of justice: to recognize and repair to the degree possible the suffering of the victims and to bring to justice the perpetrators of the acts of violence, And finally, it is a time of national reconciliation that should permit us to recuperate our wounded identity in an optimistic fashion to give ourselves a new opportunity to forge a social agreement in truly democratic conditions.

Fall 2003, Volume III, Number 1

Salomón Lerner Febres, rector of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, is the president of the Peruvian Commission of Truth and Reconciliation. This essay is a shortened version of the speech he made in the presentation of the Commission’s final report to President Alejandro Toledo in Lima on August 28, 2003.

Related Articles

Human Rights: Editor’s Letter

During the day, I edit story after story on human rights for the Fall issue of ReVista. During the evening, I work on my biography of Irma Flaquer, a courageous Guatemalan journalist who was…

ONGs en América Latina y los derechos humanos

Las ONG ofrecen mil modos de recordar la dignidad humana a los gobiernos y las sociedades. Las dos experiencias que esbozo en esta nota reflejan algunas de las estrategias asumidas por…

Peru’s Human Rights Coordinating Committee

The human rights abuses that devastated Peru from the early 1980s to the mid 1990s are once again an issue of debate in that country with the release of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation’s…