Photojournalists in a Cauldron of Violence

“THIS IS HISTORY. THIS IS MY VOCATION.”

His voice cracked and he fidgeted as he recounted the incident. He had raced out of his newspaper office to make photographs of yet another cadaver in the street. That’s part of his job—to photograph victims of his country’s slow-motion suicide.

He cut through heavy traffic on his motorcycle to beat colleagues from competing newspapers to the scene. But a pack of young men stopped him along the way. They were armed. They surrounded him. Asked if he was a cop. Demanded to know what was his business in their ‘hood. One of them reached for his motorcycle, killed the engine and pulled out the key. That’s when Juan (not his real name) feared that his colleagues soon might be making pictures of him lying lifeless in the street.

The young men, all gang members, questioned and searched him. They didn’t believe he was a photojournalist. One of them called somebody on a cell phone. The gang member handed Juan the phone so that he might explain himself to “El Jefe.”

Chocoyito the clown carries his son’s coffin after the youth was killed by gang members after being kidnapped for several days.

The “boss” told Juan not to “talk shit” about his neighborhood or about his “homies,” and assured him there would be consequences if Juan did. The gang members now knew where Juan lived, they threatened.

Juan recounted this incident during my visit to El Salvador in December 2014. It had been a long time since my last trip to El Salvador in the early 1990s. Back then I was Newsweek magazine’s contract photographer for Latin America and the Caribbean. Although my area extended from the Rio Grande along Mexico’s northern border all the way down to the tip of South America and then east to include Cuba and Haiti, I spent most my time covering the contra war in Nicaragua (where I lived for seven years) and the civil war in El Salvador. At the time, Central America was the eye of the storm. The last battleground of the Cold War.

I never liked working in El Salvador. The country had too often extracted too much blood from too many of my friends and colleagues. John Hoagland, my predecessor at Newsweek, was killed in a firefight there in 1984, one year before I signed my first contract with the magazine. In the late ‘80s I helped carry to hospital two other colleagues shot only yards from me in separate incidents while covering the conflict. They both died of their wounds. Every time I flew into the country my gut would tighten, and it would stay that way until I was beyond Salvadoran air space on a flight out—to any place other than El Salvador.

After I listened to Juan recount his run-in with the gang members and conducted phone interviews with some of his photojournalism contemporaries to report this story, I understood that the violence in El Salvador is so much more insidious now than it was when I covered the region. And I’ve come to respect and to admire even more the men and women who practice our craft under conditions unfathomable to the population at large.

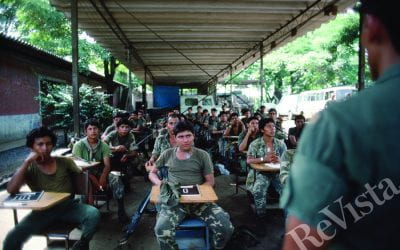

Violence in Latin America during the late 1970s and 1980s was largely characterized by left-wing insurgencies fighting to overthrow right-wing governments supported by U.S.-backed militaries. But violence in the region now is about multinational drug cartels in collusion with urban gangs. Much of the killing is gang-against-gang; “homies-against-homies,” if you will. But non-combatant civilians often are killed for resisting gang extortion or for simply showing up in the wrong barrio at the wrong time.

A TOTALLY DIFFERENT WAR

In a follow-up telephone interview from my home in Washington, D.C., I listened to Juan describing today’s conflict.

“This is a totally different war,” he said. “It’s different because we’re immersed in this cauldron of violence. It makes it hard to work.”

In comparing his situation with that of the photojournalists who covered the civil war of the 1980s, he said, “You all, at least, knew where the army was when you went out to work and accompanied the army and you knew the army wouldn’t attack you. And you were able … to see the guerrillas and their camps in the mountains and the jungle. But now, these urban militias live in our communities. They live where we live. And it’s dangerous to live in these communities.”

In another follow-up phone interview, Carlos (not his real name), a photojournalist veteran of the 1980s civil war, told me, “They (journalists) pretend not to be journalists because it’s dangerous if they (the gangs) know that they are journalists.”

THE MOST VIOLENT COUNTRY IN THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE

In its 2015 Latin America Homicide Roundup, InSight Crime reported:

“El Salvador is now the most violent country in the Western Hemisphere, registering approximately 6,650 homicides in 2015 for a staggering homicide rate of 103 per 100,000 residents. Competition among the country’s two principal street gangs, the MS13 and Mara 18, in addition to heavy-handed police tactics, contributed to the explosion of violence.”

It is in this “cauldron of violence,” as Juan put it, that photojournalists in El Salvador work. And it is the photojournalists that I focus on for this article, because they, much more than many of their “non-visual” colleagues, are exposed to that violence. Photojournalists can’t do their work over the phone or through interviews after an event or by pulling information from the Internet. Photojournalists, including still-and video journalists, have to be there, on time, as an event unfolds, to generate the images that are our craft.

“THEY ALWAYS RESPECTED YOU”

Another veteran photojournalist of the 1980s civil war (we’ll call him Pedro) told me, “There was always a chance that you would find yourself in the crossfire” between government forces and the guerilla, “but that was part of the job. In one way or another, they always respected you. In other words, they respected your work and they gave you the opportunity to do it without robbing your equipment or hurting you intentionally.

“I think journalists gained the guerrilla’s respect because they (the guerrillas) wanted the media to tell the world what was happening in El Salvador. And the army wanted the media to publicize its operations during the armed conflict. So this generated a certain trust among the warring parties and the journalists,” he said.

“But it’s very different now,” Pedro observed when I called him from Washington. In many sectors of the capital San Salvador, and even in parts of the countryside, “journalists can’t go in to do a story… because the gangs will capture him or kill him. They can disappear him. So nobody does that kind of work now. Nobody goes out to certain neighborhoods looking to do interviews with people,” he said.

Pedro should know. Gang members recently robbed one of his cameras. Gang members beat up two of his colleagues.

This violence, and the potential for violence, have reduced journalists’ ability to cover important events in their own country.

“The only thing we do is, whenever there are cadavers out there, we go out and shoot photographs at the scene of the crime—but only when the police are there,” Pedro continued. “While security forces are there. While investigators are there. Once they finish their investigation and the authorities leave, we journalists leave as well because it’s impossible to stay there without being concerned that something can happen to you. There’s an almost 90 percent possibility that something will happen to you.”

Pedro said the space in which journalists could work freely began to shrink in the late 1990s and by 2005 had vanished. And it is perhaps the survival tactics of self-censorship and limited exposure that have allowed journalists to stay alive while covering the bloodfest that is El Salvador today.

But there are exceptions. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reports that three journalists have been killed in El Salvador since 1992. It lists the killings as “Motive Confirmed,” which means that the watchdog organization is “reasonably certain that a journalist was murdered in direct reprisal for his or her work.”

Perhaps the most infamous of the killings was that of Christian Poveda, a Franco-Spanish photojournalist who made “La Vida Loca” (The Crazy Life), an internationally acclaimed documentary about the gangs. A colleague of mine with whom I worked in El Salvador and Nicaragua during the 1980s, Poveda gained the trust of, and access to, a notorious gang known as Mara 18 in a tough slum in San Salvador, the nation’s capital. In September 2009 Poveda was ambushed and shot four times in the head. Two years later a court convicted 10 gang members and a former policeman for the murder.

(Two other journalists have been killed since 1992, but the CPJ lists their deaths as “Motive Unconfirmed,” which means “the motive is unclear, but it is possible that a journalist was killed because of his or her work.”)

“WE’RE ALWAYS AFRAID”

The killings have had a profound effect on Salvadoran society as a whole, but especially on the photojournalists who cover their society.

“We journalists always try to be strong and a lot of us deny this has an impact on us but the truth is that, deep inside of ourselves, we’re always afraid, always fearful,” Pedro said. “There’s always something that keeps us up at night, or on edge, thinking about what can happen to us. There’s always anxiety surrounding our work.

“The truth is that, with our families, we always try to cover it up, so the family doesn’t see that we are being affected, so the family doesn’t worry.”

None of the photojournalists with whom I spoke believes that the violence tearing El Salvador apart will end soon. Pedro, for example, sees a “dark future” for his country’s next generation.

“Today’s young boys grow up with the goal of becoming a gang member,” he told me. “And today’s young girls grow up with the idea of becoming the partner of a gang leader…. It’s as if they have a goal to belong to a gang and to rise up in a gang, in status. And the common people just watch. They can’t do anything but just try to stay alive but they realize they are increasingly surrounded by the gangs.”

“THIS IS HISTORY. THIS IS MY VOCATION”

Juan, the photojournalist stopped by gang members, explained his motivation to continue working—despite the danger.

“The salary for journalists is not good,” but he wants to “document what’s happening in this country… like (your generation) had the opportunity to do” during the 1980s civil war.

“This conflict is a bit more clandestine and underground. You work in the street and it makes you fearful but it’s your passion, making photos, informing, documenting. This is history. This is my vocation,” he said.” “I hope they don’t take away from us the right to inform … I would like that our right to inform remains intact.”

I do too.

Spring 2016, Volume XV, Number 3

Bill Gentile is Journalist In Residence at American University in Washington, DC, and runs The Backpack Journalist, LLC. He has worked as a photojournalist in El Salvador and Nicaragua since the 1970s.

Related Articles

The Boy in the Photo

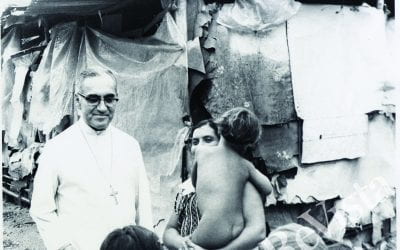

The mangy dogs strolled everywhere along the railroad track. I remembered dogs just like them from the long-ago day in La Chacra in 1979 with Archbishop Óscar Romero, just months before he was killed…

Beyond Polarization in 21st-century El Salvador

My father was a civil engineer who worked for the government during the civil war years. He specialized in roads and had to spend several days a month traveling to remote places in El Salvador. I was 10 in 1986, and I remember my mom asking my dad…

El Salvador: Editor’s Letter

I had forgotten how beautiful El Salvador is. The fragrance of ripening rose apples mixed with the tropical breeze. A mockingbird sang off in the distance. Flowers were everywhere: roses, orchids, sunflowers, bougainvillea and the creamy white izote flower…