Populist Homophobia and its Resistance

Winds in the Direction of Progress

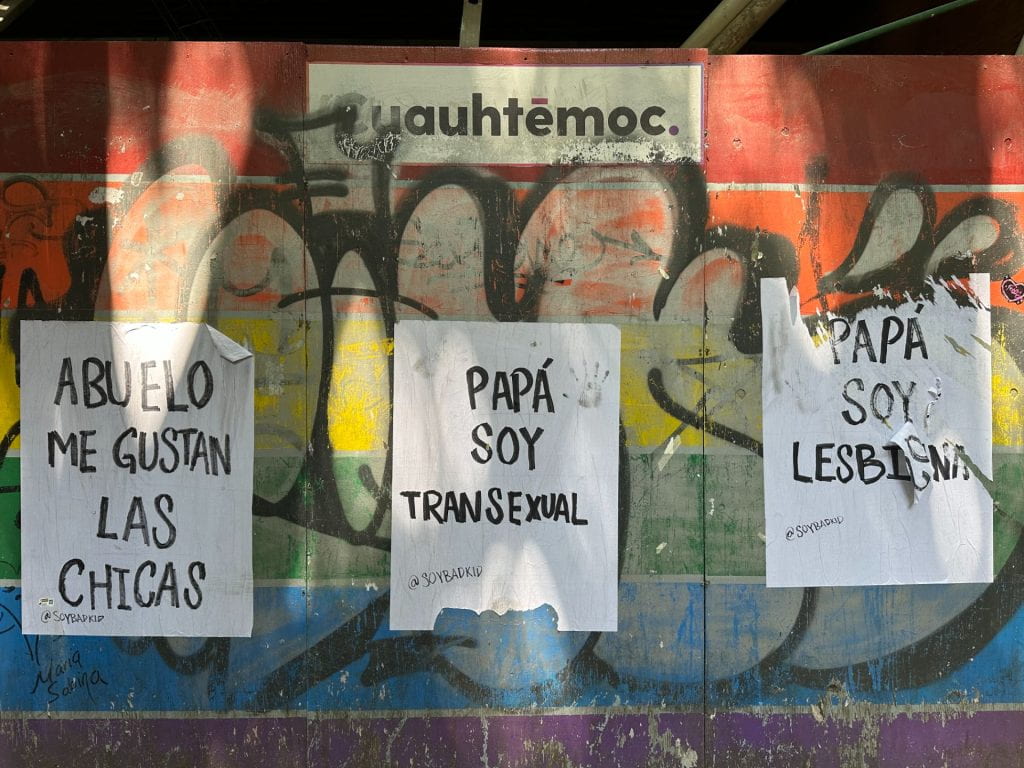

Posters along a Mexico City street in July 2023. (Photo by Michael K. Lavers)

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia. These movements frequently see the LGBTQ+ cause as a threat to be contained. Rising homophobic populism is one reason that progress on LGBTQ+ rights seems to have slowed down in the past few years. Because this type of populism is not showing signs of receding, it is easy for members of the LGBTQ+ community to feel pessimistic about the future.

However, I would like to offer a counter-narrative. While it is true that we are amid a populist-driven backlash against LGBTQ+ rights, it is also true that this backlash has been less overwhelming or successful than would have been the case two decades ago. These movements have not been able to cause as much damage as originally intended. Often, they have needed to reverse some of their positions. In some instances, they have been unseated from power.

The backlash against LGBTQ+ rights has met its resistance—in many ways the fruit of many years of productive work by activists.

The backlash

No doubt, we are living in the era of the backlash against LGBTQ+ rights. Many politicians and community leaders across the Americas are openly adopting homo- and trans-phobic (HTP) stands. Jair Bolsonaro became world famous for his virulent HTP rhetoric as both candidate and president of Brazil. He’s not the only one. Horacio Cartes in Paraguay, Jimmy Morales and Alejandro Giammattei in Guatemala, Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua, Nayib Bukele in El Salvador, Pedro Castillo in Peru, Rafael Correa in Ecuador, Evo Morales and Jeanine Áñez in Bolivia all expressed HTP preferences. Others such as Guillermo Lasso in Ecuador, Laurentino Cortizo in Panama, Andrés Manuel López Obrador in Mexico, Luis Arce in Bolivia have just been too passive.

The current backlash against LGBTQ+ progress was perhaps inevitable, considering the speed of the region’s transformation. In the span of two decades, legal codes across the region became remarkably friendly for LGBTQ+ identities.

Back in the early 1990s the region was, legally speaking, a gay desert. Democracy was widespread, but few rights were granted to LGBTQ+ people, other than decriminalization of same-sex relationships. Up until the late 1990s, institutions, firms, schools, law enforcement officials and medical professionals could be openly homophobic and suffer no consequence for it. LGBTQ+ movements were weak. Few countries even had gay pride celebrations.

But by the mid 2000s, things began to change. LGBTQ+ movements started to gain salience. Brazil in the mid 2000s was hosting the largest gay pride celebrations in the world. An avalanche of rights followed between 2005 and 2016. Civil unions proliferated. Anti-discrimination laws were introduced or reinforced. In 2010 Argentina became the second country outside of Europe, after South Africa, to legalize same-sex marriage, five years ahead of the United States. Same-sex marriage was subsequently adopted by Brazil, Uruguay, Colombia, Mexico, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador and Cuba. Colombia produced the first LGBTQ+-friendly peace agreement in the world. Argentina and Uruguay created some of the most trans-friendly legislation in the world. Many Latin American cities began to promote gay-friendly tourism. Chile’s A Fantastic Woman, a 2017 drama film about a trans woman, won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language film.

A pro-marriage equality poster at El Mejunje, an LGBTQ-friendly cultural space in Santa Clara, Cuba, on March 3, 2019. (Photo by Michael K. Lavers)

Remarkably, this rapid expansion of LGBTQ+ rights in so many countries typically occurred in the context of prevailing anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment across the general public. When many of these LGBTQ+ rights were legalized, the majority of the public was not predominantly on board. Patriarchal views dominated, homophobia and transphobia were rampant, and hate crimes were recurrent. In addition, politicians focused on other priorities or were plainly intolerant. And despite this hostile context, some countries went from hardly talking about LGBTQ+ issues to legalizing same-sex rights, sometimes in a matter of one electoral cycle. In most Latin American countries, the law changed before the public changed. And in many cases, most legal changes came by way of court orders, which gave people the feeling that they were not being consulted. Local organizations went to the courts with smart cases that challenged local heteronormative prohibitions. Often, they invoked both domestic and international human rights norms when they pressed their cases. They also conducted successful public relations campaigns to win the support of key allies across society and among key politicians. At times, they also went to international tribunals to get favorable rulings on their behalf, and thus pressure local officials to make amends. All these campaigns combined both legal savviness with public education. It was all part of concerted efforts and learning by doing. And the efforts, for the most part, paid off.

Homophobic Populism and Populist Homophobia

Given this rapid expansion of LGBTQ+ rights in the context of widespread HTP, the opportunity existed for a backlash. It didn’t take long for the opposition to LGBTQ+ rights to organize itself into action.

The way that the backlash has organized itself could be described as a marriage of convenience among three sectors: anti-pluralist populists, who oppose many forms of civil rights; socially conservative secular leaders, who are notorious for their HTP; and conservative religious groups, who invoke the Bible to oppose openly LGBTQ+ rights and any form of challenge to heteronormativity. Populist politicians with illiberal intentions realized that if they could promise to deliver socially conservative policies once in office, religious groups would not only vote for them in drives, but most importantly, forgive their autocratic infractions. Populists thus became homophobic for electoral expediency: homophobia became, in addition to a heartfelt feeling, a strategy to win the socially-conservative vote and get religious leaders to be silent (i.e., non-critical) about undemocratic moves.

The most important religious groups to be courted by populists have been the evangelical and Pentecostal communities. In the last 30 years, the religious landscape of Latin America changed enormously from a predominantly Catholic region with the eruption of the Evangelical and Pentecostal population. Back in the 1990s, Evangelicals were a small minority almost everywhere, except in Central America and the English-speaking Caribbean. Today, they are the fastest growing demographic block in most countries, and in some cases, have become the largest religious denomination.

Politically, Evangelical groups are distinctive not only for their embrace of patriarchalism (they are anti-feminist, anti-abortion, anti-LGBTQ+), but also because they are able to mobilize large numbers of people. Fundamentalist pastors have become politically active, frequently instructing church members on how to vote and encouraging financial contributions to politicians. And church members tend to follow suit. No other religion, or for that matter, non-governmental organization (NGO), in Latin America matches the capacity of these churches to mobilize voters.

Therefore, secular populists have gravitated toward evangelical churches. And the offering they make to obtain religious endorsements has been to promise support for patriarchal policies: stop abortion rights, LGBTQ+ rights, gender identity rights, public education on issues of sexuality, etc..

It was unsurprising for populists from the right, always socially conservative, to gravitate toward Evangelicals. But in Latin America and the Caribbean, even strongmen from the left have gravitated toward these churches: Raúl Castro in Cuba, Ortega in Nicaragua, Correa in Ecuador, AMLO in Mexico, Castillo in Peru, Bukele in El Salvador and Maduro in Venezuela.

In other words, populists have decided to pick on the region’s most vulnerable populations (LGBTQ+ people and women seeking abortion) in order to win the blessing of one of the region’s fastest-growing voting bloc and financially powerful NGOs. To me, the injustice behind this deal is too obvious.

Just as we have seen the rise of homophobic populism, we have also seen the rise of populist homophobia. This type of homophobia consists of socially-conservative (often religious) leaders framing their HTP positions in populist terms. If the populist playbook is to divide the electorate between “the people” versus depraved “elites,” the populist homophobic playbook is to argue that LGBTQ+ groups represent the depraved elite whose agenda is too extreme, too radical, too foreign-influenced and too imposing on majorities.

Another feature of the homophobic populist playbook is to advance the idea that its aim is to promote “public goods.” When they attack what they call “gender ideology,” populist homophobes typically argue that what they are really doing is defending collective goods such as freedom of religion, autonomy of families and protection of children. This is disingenuous. They are dressing up their sectarianism with a pretense for public mindedness.

The backlash against the backlash

Nothing has been more damaging to the LGBTQ+ agenda in the 21st century than the rise of homophobic populism and populist homophobia on the part of politicians and religious leaders. That said, it is important to take note of the political reverses experienced by these forces.

A pro-LGBTQ decal in El Dorado International Airport in Bogotá, Colombia (Photo by Michael K. Lavers)

One of the fiercest battlegrounds was Colombia in 2016. When President Santos unveiled his peace agreement with the guerrilla group Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC)—the first peace agreement in the world to mention the need for reparations for LGBTQ+ victims of the conflict—conservative leader Álvaro Uribe mobilized the evangelical vote, urging them to vote against the agreement in a referendum. Uribe succeeded in defeating the agreement, leading to a rewrite of the agreement. However, LGBTQ+ provisions in the end remained in place. In addition, none of the LGBTQ+ laws obtained in Colombia were derogated, and an important LGBTQ+ politician who led the resistance against populist homophobia, Claudia López, soared in popularity, to the point where she eventually became mayor of Bogotá. In fact, the more Uribismo turned to evangelicals, the weaker his movement eventually became, electorally at least.

Photo by Michael K. Lavers

Similar setbacks have been recorded elsewhere. While AMLO made an electoral pact with an evangelical party as candidate, he has stopped short of reversing the progress made on LGBTQ+ rights; there are too many groups within (and outside) his coalition challenging his social conservatism. In Bolivia and Peru, socially conservative presidents (interim president Áñez and short-lived president Castillo) were never popular in part for their social conservatism. In Chile, Costa Rica and Venezuela, evangelical pastors running for the presidency have been defeated at the polls. In Guatemala, after promoting a pro-evangelical agenda, president Giammattei had to turn against evangelicals in congress and veto their Bill 5272, one of the most punitive anti-abortion and anti-LGBTQ+ proposals in the Americas—the bill was just too extreme and provoked huge marches. And in 2023, when Guatemalan front-runner candidate Sandra Torres gravitated toward evangelical groups in the second round, she lost votes, and subsequently, the election.

Perhaps the biggest test of the argument that social conservatism is suffering setbacks in Latin America is the case of Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, one of the most vocal HTP presidents in Latin America in decades. Like Donald Trump in the United States, Bolsonaro forged an overt alliance with evangelicals both during the campaign and in office. In a classic expression of homophobic populism, he stated, “The state is Christian and those who are against it can leave. The minority must bow to the majority.” He continuously expressed his intention to reverse LGBTQ+ gains. He appointed openly HTP pastors to key cabinet positions. And under his administration, hate crimes against trans people increased, no doubt influenced by Bolsonaro’s own HTP rhetoric.

And yet, Bolsonaro was unable to terminate many of the rights in place for the LGBTQ+ community. Furthermore, he never managed to expand his electoral base. And like Trump, he was one of the few incumbent presidents in the Americas to be defeated in a re-election bid.

Transgender Congresswoman Erika Hilton speaks at a pro-Lula rally in São Paulo on Oct. 5, 2022. (Photo by Michael K. Lavers)

All the political reverses experienced by homophobic populist leaders have multiple causes. These presidents and leaders get in trouble for a variety of reasons, not just their social conservatism or alliances with fundamentalists. In some cases, their homo- and transphobia may not even be the most important reason for their political setbacks. Perhaps. But I do think that their overt form of homophobia is always a double-edged sword. Their homophobia allows them to gain allies (socially conservative voters and religious voters), but also precludes them from growing their base. Their homophobia also provokes significant opposition. Today, political leaders who openly call for policies hoping to reaffirm or even restore the patriarchy are becoming repulsive to an increasingly larger number of voters.

Who are these voters who find populist homophobia repulsive in Latin America and the Caribbean? It includes a combination of secular, anti-clerical and irreligious people. It also includes progressive Catholics or Catholics who attend church infrequently. And it especially includes young people, more so if they are college-educated. Young individuals tend to be more pro-LGBTQ+ friendly than their older cohorts, sometimes even more accepting than elements of the left.

The expansion of the number of voters who find homo- and transphobia repulsive is one of the strongest achievements of LGBTQ+ activists in Latin America and the Caribbean in the 21st century. It is an epochal public relations triumph. LGBTQ+ movements may not have been able to conquer the hearts and minds of every sector of the electorate (and perhaps never will), but in winning over large chunks of the younger generations, they have probably won the most important sector.

LGBTQ+ movements always realized that any effort to change government policy, business practices and institutional orientations required, first and foremost, a public relations win. They needed to convince citizens, not just leaders, that democracy is lacking if there is no acceptance of diverse sexualities and gender expressions. Judged in terms of their ability to convince ordinary people that no sexual diversity = no democracy, LGBTQ+ activists deserve high praise.

In short, while social conservatism and HTP politicians seem ascendant today, it is also true that the anti-patriarchal sector of the Latin American and Caribbean electorate is the strongest it has been in generations. Many Latin Americans are increasingly uncomfortable with policies that openly reify the patriarchy, and terribly repulsed by overt forms of homo- and trans-phobia. These citizens are placing brakes on the expansion of social conservatism. The rise of this counter-bloc is one of the most significant demographic and cultural changes in the region in decades. It is one reason LGBTQ+ people and their allies should not feel that gloomy about the political times we are in. Despite adverse winds, on the issue of sexuality rights, trends are still pointing in the direction of progress.

Javier Corrales (Harvard Ph.D. ‘96) is Dwight W. Morrow 1895 Professor of Political Science at Amherst College, in Amherst, MA. He was a also a DRCLAS Fellow. His latest book is titled Autocracy Rising (Brookings Institution Press, 2022). Parts of this essay draw from his book The Politics of LGBTQ Rights Expansion in Latin America and Caribbean (Cambridge Elements, Cambridge University Press), and, “Homophobic Populism,” co-authored with Jack Kiryk (Oxford Research Encyclopedia). Contact: jcorrales@amherst.edu

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.

A Review of In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations

Merilee Grindle’s fascinating biography of Mexican-American anthropologist Zelia Nuttall (1857-1933), In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations, is a welcome sign that the field of Nutall studies is expanding.

Imagining the Queer Future of Latin America: A Look at “Carmín Tropical”

In recent years, queer studies have made significant strides in various domains worldwide, including cinema, business, television, academia, street activism, politics, and sports.