Prejudice and Pride

Avoiding and Encountering Blackness in the Nation of the Black Virgin

What does it mean to be black in Central America? From the Garifuna people along the Atlantic Coast to the descendants of Jamaican and other West Indian groups throughout the isthmus, the region’s citizens have become increasingly self-conscious, visible and interested in their Afrodescendent legacy—to a degree. This reawakening has largely been associated with ethnically and linguistically distinct populations, recognizing and even celebrating them while once again reinscribing blackness as something belonging to “others.” However, only very recently has there been any serious attempt to reposition blackness at the center of dominant historical narratives of mestizo nationhood and contemporary self-identification.

How far we have come in recent times might best be measured by comparing and contrasting early 20th-century imagery, and its now often distorted memory, with early 21st century visual and film representations. Nowhere is this more striking than in Costa Rica, the nation most invested in a white identity, paradoxically juxtaposed with its veneration of a black patron saint and protectress, La Virgen de los Angeles. Costa Rican national identity has long involved invidious comparisons with its Central American neighbors, from the very first official histories and promotional publications in the mid-19th century to the present. Beyond their neighbors’ all too frequent civil wars, greater poverty and inequality, a central element in all such comparisons has been the claim that, because of its colonial-era isolation and poverty, Costa Ricans descend overwhelmingly from Spanish peasant forebearers, with far less indigenous heritage, the “white legend” of national origins, identity and distinction. Blackness or African descent has been virtually ignored as a source of national origins and identity, consigned to foreign or more recent immigrants and distinctly minority groups in peripheral regions, as has been the case elsewhere in Central America.

Just as with many a Central American and Costa Rican president during the 19th century, Afrodescendant public figures in the early 20th century made a point of ignoring their origins, whether in the case of Nicaragua’s Rubén Darío or the Costa Rican Communist Party militant, legendary children’s literature author, and Benemérita de la Patria, María Isabel Carvajal, better known by her pen name Carmen Lyra. Many such intellectual and political gures aligned themselves with mestizo nationalist ideals of the day, at times employing or echoing overtly anti-black imagery and rhetoric. More recently, at times no less controversially, Afro-mestizo cultural expressions have emerged that not only embrace blackness but seek to reposition it at the center of national history and mythology. This interrogation of public attitudes and lived experiences reveal a mine eld of silences and ambiguities surrounding blackness and racial perceptions among the very mestizo majority populations for whom blackness may remain a shared, distant ancestry and religious tradition, but also something deeply other—even when this blackness is inescapably part of their daily life and community.

In this more recent phenomenon, the documentary film “Si no es Dinga …” and its central gure/narrator, Leda Artavia Rojas, provides a needed perspective on questions being intensely reexamined by this generation of both public intellectuals and young people. We will explore the lives and images of Carmen Lyra and Leda Artavia to enter into the hall of mirrors that is blackness in the white nation of Costa Rica.

CARMEN LYRA AND COLOR-BLIND POLITICS

María Isabel Carvajal, or Carmen Lyra (1887-1949), was born to a single mother, raised in poverty in San José, and died in exile in Mexico shortly after the 1948 Revolution that expelled her and banned the Communist Party she had co-founded. At age 17, she graduated from the Girls’ High School (Colegio de Señoritas) in San José, and within a decade she began to publish her first stories. She played a central role in organizing the female-led and occasionally violent street demonstrations, including the burning of the pro-regime newspaper, that brought down Costa Rica’s last military dictatorship in 1919. The new civilian administration rewarded her with a fellowship the following year to study early childhood education in France and Italy. Upon her return, she helped found the first Montessori School in San José and became the first children’s literature professor at the teacher training school in Heredia. Her radical politics never failed to upset her relations with institutions and employers, leading to a life-long collaboration with individuals who shared her ideas and jointly founded the Communist Party with her in 1931.

Beyond partisan politics, however, Carmen Lyra’s lasting fame came as the author of classic children’s literature, in particular, Cuentos de Mi Tía Panchita. The collection gave voice to countless folk tales familiar to generations of Costa Rican children, including several tales of African origin such as the Tío Conejo (Brer Rabbit) stories. The only explicitly “colorized” or color-based fairy tale in that collection was titled, “La Negra y la Rubia,” (The Black and the Blond Girls). Contemporary literary analysts have puzzled over and criticized this fable’s overtly anti-black and pro-Christian imagery of favor and redemption, particularly in a nation whose patron saint and virgin is popularly known as “La Negrita.”

However, like many such expressions of anti-black orthodoxy by 19th- and 20th-century Afro-mestizos elsewhere in Central America, the fable could be read against the grain rather than simply as yet another pledge of allegiance to white supremacist national iconography. Lyra’s writings, both political and literary, give no hint of a fondness for irony bordering on satire, parody or sarcasm, but she was not an orthodox author of socialist realism either, given her choice of the genre of fairy tales adapted to the local context, among the rst to be written to sound like popular speech. The fable of the favored Rubia and the disparaged Negra could thus be read as a not-so-veiled allegory describing the social and psychic costs of deeply entrenched discriminatory attitudes and beliefs the author herself was perhaps only too aware of.

Literary analysts who have yet to detect or suspect such an undertext in Lyra’s story also rescued from national historical amnesia a particularly revealing and powerful photograph of the youthful writer turned militant. At the ceremony to found the Cátedra Carmen Lyra at the Universidad Nacional (the former teacher training school in Heredia) in 2015, they publicized an image used by her friend and admirer, former Education Minister María Eugenia Dengo Obregón, in her homage to Lyra as one of many iconic Costa Rican educators in her book, Tierra de Maestros.

As was common throughout Central America then and now, both official and popular historical memory whitens and softens their icons with the passage of time. Carmen Lyra, communist exile and official villain for more than half a century, was rebranded as a popular martyr when she became Benemérita de la Patria in 2016. Her newly honorific, semi-official image graces the largest denomination of local currency in circulation, the 20,000 colón note.

Carmen Lyra may well have cultivated the austere, proletarian “look” in her many public images after returning from Europe and founding the CP, but none compares with the striking beauty of that youthful image, of the Afromestiza rebrand poised to commit her life to the “people’s cause.” Her contemporary and posthumous supporters have tirelessly noted her illegitimate birth and childhood poverty, but in the centuries-old tradition of assimilationist silence, politely ignored her Afrodescendance.

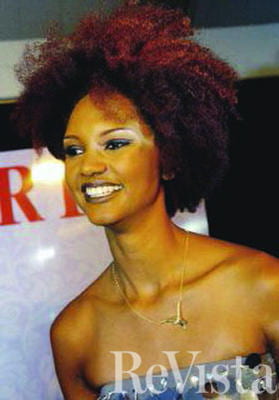

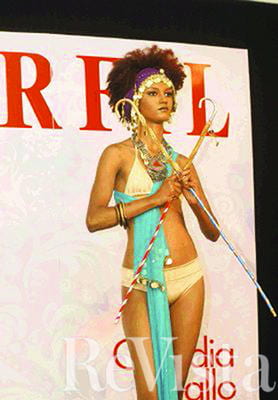

LEDA ARTAVIA: FROM HIGH FASHION TO DINGA’S LEADING LADY

In late 2014, the screening of the Costa Rican documentary film Si no es Dinga became a local watershed—a “happening.” Produced by Isis Campos Zeledón and Rodrigo “Kike” Molina Figuls, the 52-minute film explores a range of Costa Ricans’ (mis)understandings of their relationship to blackness. The producers use a variety of tropes and strategies, beginning with the title itself which comes from the colonial-era saying from Peru, “Si no es de Dinga es de Mandinga,” referring to race and cultural mixes having either indigenous (Inca/Inga/Dinga) or African (Mandinga) roots. They proceed to explore how very common words and expressions, as well as local musical traditions, are clearly unrecognized as African in origin. The film uses interviews with a range of men and women on the street, as well as with academic specialists, to try to understand how this peculiar compartmentalization of attitudes came to be. An often reflexive pride in national whiteness coexists alongside a quotidian recognition of dark-skinned mixedness, as well as an abiding reverence for “La Negrita” and the pilgrimage to her shrine in the colonial capital of Cartago each August 2.

The driving force of the documentary, however, is the narrative voice and on-screen presence of Leda Artavia Rojas. Part youthful everywoman and explorer leading the viewer on a journey of discovery, more profoundly the muse offering a window on the world of Costa Rican stereotypes and misperceptions about blackness, she offers not only first hand, lived experience, but access to her own complex family history. Reframing the documentary enterprise more fundamentally as if it were simply “getting to know someone,” and that someone as engaging and disarming as Leda Artavia, proves a brilliant strategy to avoid the traditional academic pitfalls of would-be objectivity and didacticism.

As she revisits various neighborhoods from her childhood, she reminds viewers that she grew up entirely in the Central Valley. Somewhere between joke and lament, she wonders aloud why she is always asked if she is from Limón or why she does not like “rice and beans”— both references invoke local code for identifying “blackness” associated with West Indian immigrants from the Atlantic coast. Or, why do people who seem to want to be polite, assure her that she is “not really” black. Later in the film, many of the academic informants enter into conversations with Leda, seeking to explain the very long history of willful ignorance of colonial black populations’ role in race mixture, the emergence of imagined “mestizo” majorities, and the denial of blackness as a form of polite society’s partial acceptance of Hispanic Afrodescendants.

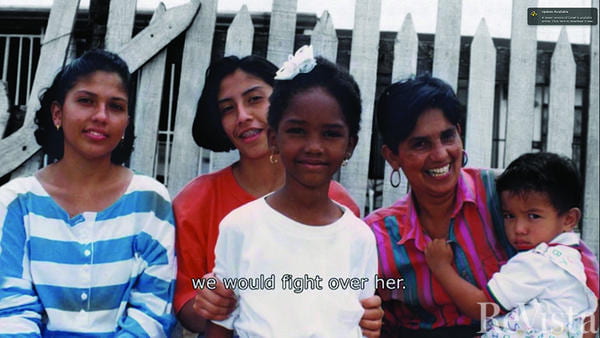

Dinga’s story deepens further in a series of on-camera conversations Leda has with her older sisters about their experiences with color diversity within the family. In a bittersweet exchange haunted by the all-too-fresh memories of the premature death of their mother, the discussion ranges from their grandfather’s opposition to her relationship with Leda’s father, how her color difference was perceived by the sisters, and how they identify themselves in color and ethnic terms. In conversation with genealogist Mauricio Meléndez Obando, they are able to identify multiple generations of their forebearers from parish records and family album photographs, learning ironically that he and they are in fact not-so-distant cousins. These records show that they all descend from distant indigenous, Spanish and African forebearers, however similar or different their phenotypes in the current generation, and also display an age-long, strong preference for Spanish and mestizo identifiers.

As her sisters leaf through family photos and images, many Costa Rican viewers of the film are forced to juggle their own multiple images of Leda. In Dinga she presents herself as the unassuming, casually dressed, twenty-something narrator confronting her identity and positionality at home in the Central Valley, but others know her already as the high- fashion model, winner of national prize competitions. Treading the path taken by Carmen Lyra in reverse, recognition for Leda Artavia involves foreign travel, study and work in Europe, Asia and the Americas, not as prelude to a career choice at home but as inherent to the career choice itself. Nor does it involve silencing or submerging her Afrodescendance. Far from it, both at home and abroad it involves a foregrounding of blackness, its beauty and its burdens, in a society which has been loath to recognize it; a society whose imagined ethnic homogeneity means that only Spanish and indigenous heritages constitute the mythical national “we” versus the “others.”

Costa Rica is home to many a paradox—and not just that a self- proclaimed white nation venerates a black Virgin as patron saint. At least half a dozen of Costa Rica’s presidents trace their lineage to an 18th-century enslaved woman, Ana Cardoso, whose invisibility can perhaps be gauged by the fact that generations of schoolchildren continue to voice disbelief when told that Africans and slavery actually existed in colonial Costa Rica. Long a regional bulwark of anti-Communist politics, here once thrived Carmen Lyra’s Communist party-led nationalist reform well before Italy branded its own version as Euro- Communism. Today those less discerning among its politicians anguish over how to join the “developed” world—in a society already as transnational, postmodern and multiculural as any on the planet.

Carmen Lyra lived and struggled in an era of proletarian internationalism turned nationalist, of pro-mestizaje ideologies that ignored or excluded blackness. Both ideologies claimed to resolve their own paradoxes with healthy doses of optimism, self-sacrifice, and silence. Carmen Lyra’s Afrodescendance was politely ignored by her comrades-in-arms then and long thereafter. Leda Artavia was born at the dawn of an era of resurgent transnationalism and multicultural ethnic identity politics. For her generation, blackness has become a central existential question of who am I, where do I come from, and why am I perpetually surrounded by mistaken assumptions? As diametrically opposed as the two eras and their paths may seem to us, these two Afro-mestizas shared a struggle for recognition, always subject to reframing by friend and foe alike, one never fully within their grasp perhaps, but a struggle neither would shrink from.

Winter 2018, Volume XVII, Number 2

Lowell Gudmundson (Mount Holyoke College) is the co-editor of Blacks and Blackness in Central America (Duke University Press 2010; EUNED Costa Rica 2012). His most recent book is Costa Rica después del café: La era cooperativa en la historia y la memoria.

Related Articles

Afro-Latin Americans: Editor’s Letter

My dear friend and photographer Richard Cross (R.I.P.) introduced me to the unexpected world of San Basilio de Palenque in Colombia in 1977. He was then working closely with Colombian anthropologist Nina de Friedemann, and I’d been called upon by Sports Illustrated to…

Witches, Wives, Secretaries and Black Feminists

The issue of gender has been front and center for me, both as a subject of my fieldwork on black politics in Latin America, and how I conducted that research, particularly in how I…

Compañeros En Salud

English + Español

I have lived in non-indigenous rural Chiapas in southern Mexico since 2013, working with Compañeros En Salud (CES)—a Harvard af liated non-profit organization that partnered with…