Reconfiguring Childhood

Boys and Girls Growing Up Global

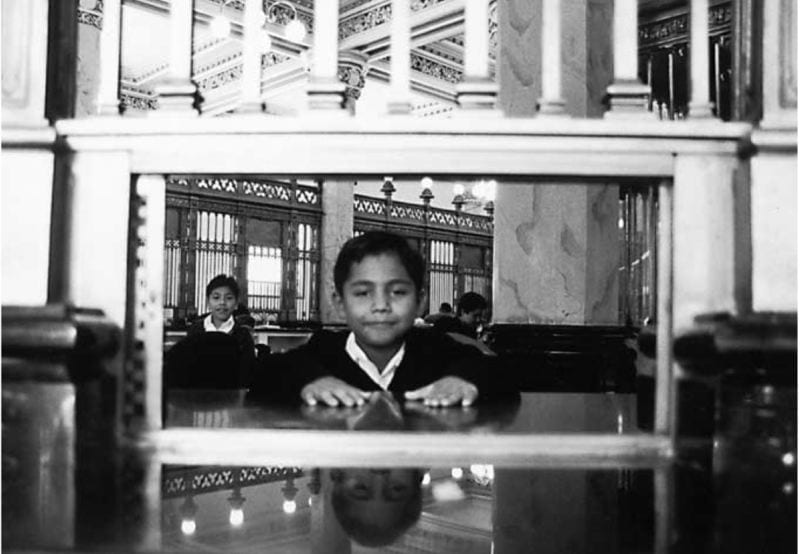

A child works in the Mexico City post office. Photo by Carin Zissis

Children are a spur, a commitment, a way of imagining the future—but all too often these sorts of phrases just rattle around a vacuum, their utterance the beginning and end of the commitment. We emphasize “the best interests of the child,” but this gloss provides a moral imperative to all manner of uncompleted projects and unfulfilled policies. Likewise, the use of children’s images or presence in public forums of all types gives a patina of honorableness to practices and plans that never actually make good on the promissory note of childhood. The 1992 Rio Earth Summit is a notable example. Such saccharine calls to futurity often bypass the presents and presence of flesh-and-blood children. Actual boys and girls, of course, live in the sedimented residues of the past, their life chances worked out—and mired—in particular historical geographies and political economies that are not always accommodating to their forging livable futures. At best, these geographies are shifting and uneven. Even the most local circumstances—conditions of the body, the home, the neighborhood—are interstitial with processes at larger scales. The imperatives of capitalist-driven “globalization,” for instance, alter the terrains of children and childhood, rendering the previously taken-for-granted up for grabs as commitments to particular places and paths of social reproduction are wrenched. I’ve focused much of my research on these altered terrains and their consequences for children coming of age in vastly different places, most notably rural Sudan and the urban U.S., in particular central and East Harlem. The common experiences of young people in both places brought rejigging the practices and commitments of social reproduction, and the non-coincident ways that children were not learning what they probably would need to know as they faced the shifting circumstances of capitalist globalism, compel me to argue that “globalization” must be made sensible at the scale of children’s everyday lives if it is to be understood at all. My experiences in the arid lands of Sudan and the streets of New York lead me to ask what these processes may mean for Latin American children, whether in sprawling São Paulo or the Chilean desert.

Winter 2004, Volume III, Number 2

Cindi Katz is Professor of Geography in Environmental Psychology and Women’s Studies at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. She is a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard for 2003-4. Her book, Growing Up Global: Economic Restructuring and Children’s Everyday Lives (Minnesota) will be published in 2004. Her current work concerns 20th-century U.S. childhood.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: The Children

A blue whale spurts water joyfully into an Andean sky on my office door. A rainbow glitters among a feast of animals and palm trees. Geometrical lightning tosses tiny houses into the air with the force of a tropical hurricane.

Centroamerica

Cuando Pedro Pirir, fue despedido del taller mecánico donde trabajaba desde hacía muchos años, experimentó una sensación de injusticia y pena que luego se transformó en una voluntad…

Irregular Armed Forces and their Role in Politics and State Formation

As I sat in heavy traffic in the back of a police car during rush hour in the grimy northern zone of Rio de Janeiro, I studied the faces of drivers in neighboring cars, wondering what they thought of…