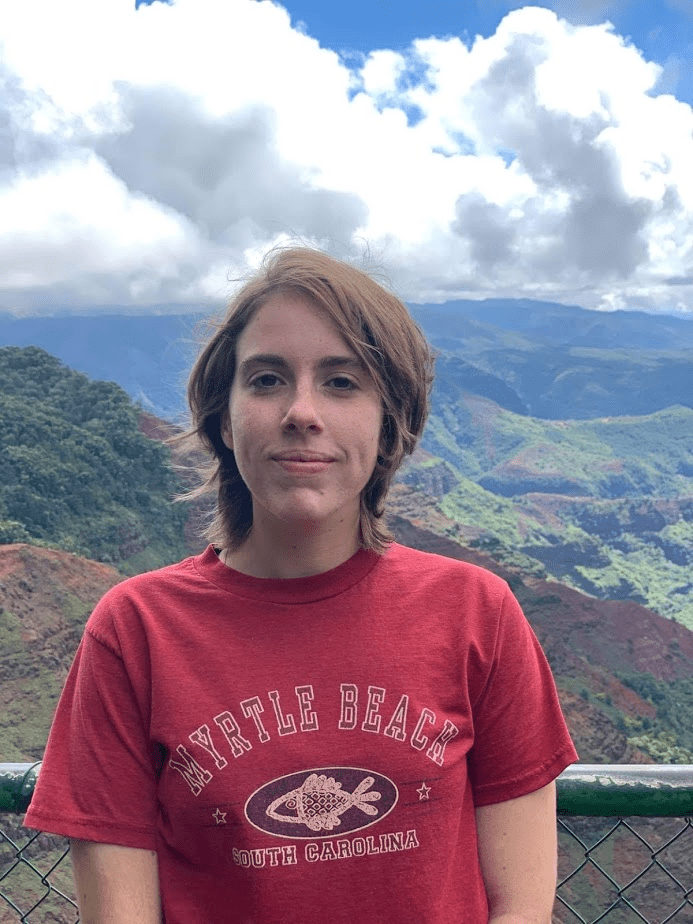

About the Author

Ana Mundaca is a junior in Harvard’s best house (Lowell House) studying East Asian Studies and Economics. She likes to draw and read comics in her free time. She recently rescued a stray cat and originally named him “Mofongo” but renamed him “Mr. Muffin” after people said it was too hard to pronounce.

Remembering Chilean Folktales

When you were growing up, you probably loved to listen to bedtime stories before bed. If you are from the United States, you may have heard tales of princesses being rescued by princes, monkeys jumping on beds and injuring themselves, or witches luring children into their homes to fatten and eat them. If you are from South America, the stories you heard were likely much different and involved recurrent characters such as friendly dwarves, evil naturopath-witches, and talking animals of questionable morality. My grandfather immigrated from Chile to the United States in his teens. While he assimilated to American culture in many ways, the stories of his youth never left him. Below I describe a few of my favorite Chilean folktales passed down from my grandfather to me in my childhood, accompanied with brilliant illustrations done by yours truly.

The Christmas Dog: This first story is more of a legend, and it is one that I have only been able to corroborate with my brother. A seven-foot bipedal black dog visits random households during the Christmas season and breaks their plates in their kitchens. I remember the dog specifically breaking plates in the kitchen, meaning bowls in the kitchen were safe, as were plates in the dining room. There is no way to stop this yuletide terror.

Hostage Clouds: There once was a mountain that fell in love with a soft, fluffy cloud. The feelings were mutual, so they got married. The mountain, suddenly possessive of his new wife, decides to lock her in one of his caves so that she can not escape or have her beauty be appreciated by anyone else. During this time the cloud bore a child, also a cloud. One day, the cloud escapes the cave with her child and almost makes it fully out of the mountain before the mountain notices. While the mountain isn’t able to stop his wife, he does trap the child back in the cave and threaten the mother with harming the girl, but the mother is swept away by the wind before being able to save her child. The mountain doesn’t want his daughter to escape like his wife did, so he hires an unassuming dwarf to watch over the child in the cave and prevent her escape. Would you like to take a guess as to how the mountain is paying said kind dwarf to watch his daughter? Well, if the dwarf is able to raise the child and keep her in the cave until the legal age of consent, he can take the cloud as his wife. The cloud, somehow wise to this, rejects the plan, and melts herself into a puddle rather than be raised by a creep and be turned into his wife.

Corn, Poppies, and Tragedy: This is perhaps the most overtly moralistic of all Chilean folktales I have heard. There was once a spritely young girl who was the center of attention in her town. Everyone loved her energy and spark — except for her parents, apparently, who spent most of their time trying to control the young girl. “Please stop running around amok outside,” they’d say. “The animals may eat you, the people may scold you, bad things may happen.” But every excuse they came up with fell flat since, as you may recall, animals can often speak in Chile, and they all vowed to not hurt the girl since they loved her so much. One day, the little girl felt a little more crazed than usual and decided to play in the corn field near the town. I am not sure how many of you have seen a corn field in real life, so for your reference I’ll inform you that stalks of corn can grow up to eight feet tall. Due to the imposing height of the corn, the girl gets lost, and no one can find her. Eventually the entire village is mobilized to find the missing wild child. After a long night of searching, they come upon a clearing in the field where wild red poppies have begun to grow. The village know-it-all proclaims that a witch has killed the young girl and left the flowers so that the villagers could always remember her. How sweet.

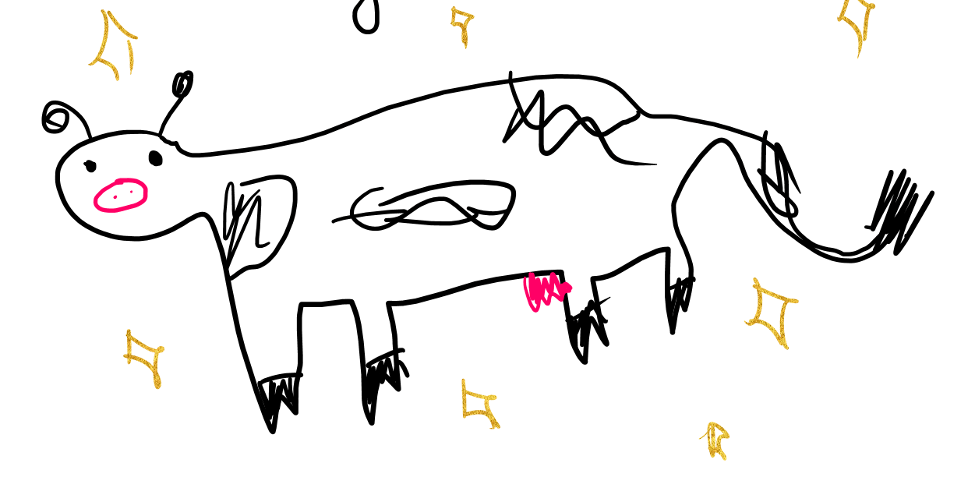

The Magic Cow: This story is by far my favorite. There once was a family that owned a cow. But they were poor, so they needed to sell the cow. The son begged his father to not sell her since he loved the animal so much, but the father insisted on it. While bringing the cow to the market, he came across an old woman who asked if she could ride the man’s cow across the river since she was too weak to cross it on her own. Displaying typical human foolishness in his desire to help others, the man agrees and is subsequently kidnapped by the old woman.

It turns out she is a witch, and she sucks him down to the bottom of the river using a water vortex. The cow escapes unscathed, however, and returns to her family. The wife, now a widow with two children, decides to move to an oceanside town where a few days later her daughter drowns while playing in the ocean with her brother. The brother comes back ashore, sobbing, and is met with consoling words from the cow. The cow tells the boy she has a plan to save his father and sister. The boy must first kill the cow, pry her eyes out, skin her, throw her skin into the sea, and then use her eyes as binoculars to find the witch’s lair. Then, in emergencies, he must pluck the hairs off her tail and transform them into whatever he needs to save himself.

The boy initially rejects this plan, as he does not want to hurt his dear friend, but eventually relents. The cow’s eyes guide him to the witch’s hideout in the middle of the sea, which he rides to using the sailboat the cow’s carcass turned into when it hit the water. When he runs out of wind, he plucks a hair from the cow’s tail to transform it into the winds he needs to get to the witch. After a long journey at sea, he arrives, saves his family, and incapacitates the witch. After arriving home and reuniting with their mother, the boy drags the cow-boat to the shore and places the remains of the cow and her eyes next to it. He was initially planning on a burial, but lightning strikes the cow and she returns to her normal bovine state and was from then on treated like a valuable member of the family.

After reading these stories, you may be surprised that they are routinely told to young children given the pervasiveness of death and adult themes. That was certainly my reaction upon rereading these stories in preparation for my recent presentation to the Lowell House community on the topic. I initially assumed these stories stressed me as a child, and I was puzzled as to the seeming lack of a message in any of the stories. Members of the audience similarly commented on the lack of lessons in these stories. In Western traditions you have moralistic Aesop fables and you have American folktales of “common folk” working hard to bring about their dreams; in Chilean folktales you have magical cows and ants, evil mountains, and lots of seemingly pointless death. While I agree there are no morals in the Chilean folktales told to me and my grandfather in our youths, I push back against the notion that no lessons or values are communicated in these stories. The stories presented here, while seemingly random, are all connected by a palpable chaos that rules the worlds these stories take place in. The successful characters are the ones who show kindness to and rely on others, while the unsuccessful characters are the ones who attempt to control the world around them. In comparison to the American stories which taught me to work hard to bring about my own fate, Chilean folktales taught me to adapt to my situation, to make the best of what I had, and to show compassion to others and believe in kindness even if it didn’t make sense to do so. Through his telling of folk tales and his actions, this is what my grandfather has taught me.

To me, these stories are an extension of his understanding of me and a testament to his kindness and desire to help others. These stories, transformed over generations of indigenous storytelling, hybridized with European stories and passed down through multiple languages will stay with me and many others no matter when or where we are. That, in itself, is a testament to the magic that these stories profess exists in our world.

More Student Views

Beyond Presence: Building Kichwa Community at Harvard

I recently had the pleasure of reuniting with Américo Mendoza-Mori, current assistant professor at St Olaf’s College, at my current institution and alma mater, the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Professor Mendoza-Mori, who was invited to Madison by the university’s Latin American, Caribbean, and Iberian Studies Program, shared how Indigenous languages and knowledges can reshape the ways universities teach, research and engage with communities, both local and abroad.

Of Salamanders and Spirits

I probably could’ve chosen a better day to visit the CIIDIR-IPN for the first time. It was the last week of September and the city had come to a full stop. Citizens barricaded the streets with tarps and plastic chairs, and protest banners covered the walls of the Edificio de Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca, all demanding fair wages for the state’s educators. It was my first (but certainly not my last) encounter with the fierce political activism that Oaxaca is known for.

Public Universities in Peru

Visits to two public universities in Peru over the last two summers helped deepen my understanding of the system and explore some ideas for my own research. The first summer, I began visiting the National University of San Marcos (UNMSM) to learn about historical admissions processes and search for lists of applicants and admitted students. I wanted to identify those students and follow their educational, professional and political trajectories at one of the country’s most important universities. In the summer of 2025, I once again visited UNMSM in Lima and traveled to Cusco to visit the National University of San Antonio Abad del Cusco (UNSAAC). This time, I conducted interviews with professors and student representatives to learn about their experiences and perspectives on higher-education policies such as faculty salary reforms and the processes for the hiring and promotion of professors.