Restoring a Ravaged Venezuelan Coastline

Dramatic floods ravaged the Caracas seaside known as the Littoral in December 1999, ripping up houses and literally re-shaping the coastline and beaches. Less than a year later, I joined several Venezuelan colleagues in leading a joint urban design studio in the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University (GSD) and in the Urban Design Masters Program at the Universidad Metropolitana (Unimet) in Caracas, Venezuela.

Dramatic floods ravaged the Caracas seaside known as the Littoral in December 1999, ripping up houses and literally re-shaping the coastline and beaches. Less than a year later, I joined several Venezuelan colleagues in leading a joint urban design studio in the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University (GSD) and in the Urban Design Masters Program at the Universidad Metropolitana (Unimet) in Caracas, Venezuela.

The Venezuelan Ministry of Science and Technology had asked the Unimet Program to prepare redevelopment proposals and provide tools to implement the recovery program. Tourism was an integral part of that recovery strategy. Indeed, the disaster and the subsequent joint design studio project shaped radical new ways of thinking about the nature of tourism in the Littoral community.

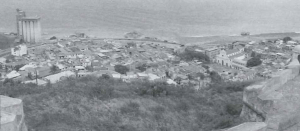

The coastline had long been the scene of Caracas residents’ beach exodus to sun and relax. But almost no one looked twice at the original but previously neglected 16th century Spanish colonial town, La Guaira, including three existing forts. Thinking about recovery meant thinking about tourism, and even the possibility of international tourism.

The Unimet study gathered together a broad multidisciplinary team to produce a Conceptual Vision for the recovery. Working alongside Unimet Professors David Gouverneur and Alfredo Landaeta, as well as students from the Unimet Urban Design Masters Program, GSD students and faculty were able to combine their resources and talents to further advance the initial proposals.

We found ourselves confronted with an extremely urgent situation. New environmental and physical designs were challenging enough, but real-world implementation issues made our tasks daunting. Global climatic changes are increasing the likelihood of similar events occurring in the near future, especially in areas where urban growth has taken place with limited planning and development controls, underscoring the critical importance of this academic joint venture.

The studios focused on the portion of the coastline extending from Macuto to the west including the Port of La Guaira and Simón Bolívar International Airport, both in need of re-engineering. Sprawling barrios on surrounding hillsides, bordering the historic districts ring these facilities. This is an area of great potential and great need. It houses the majority of the resident population of the Littoral (many in environmentally unstable areas), provides significant employment, and contains large expanses of underutilized land.

Although historically there has been very little international tourism in this area, the regular weekend beach exodus from Caracas has created an intensely symbiotic tourist relationship with the capital. Caracas weekenders gather frequently, particularly on portions of the Littoral further to the east. The mudslides of December 1999 dramatically changed this landscape, removing built-up areas with enormous loss of life and property, and radically calling into question previous patterns of use and occupation. In the section examined by the joint studio, a rough estimate suggested that some 20,000 people (4,000 households) were in need of relocation out of the floodplain.

The fact that so much had to be re-built sharpened perceptions of the previous trends, making it possible to question them and imagine very different outcomes. Inevitably, part of that re-consideration involved the role of tourism as one of the engines of growth, not in isolation, but as part of a highly intertwined set of questions that were addressed in the studio such as:

- How to treat the Littoral as a unique example of living with severe geographic limitations and the risk posed by nature?

- How to deal with flood control issues and at the same time provide environmental conditions that may reinforce the recreational nature of the Littoral, create a new urban identity, and attract new investment?

- How to create an attractive built environment, take advantage of the scenic values of the site, and protect the fragile ecosystems of the adjacent National Park from illegal occupation?

With an intensive site visit during January 2001, Harvard students were able to view the existing conditions in the devastated coastal fringe first hand. They experienced the relationship of the Littoral to the greater Metropolitan Area of Caracas and gained sensitivity to the capital’s particular urban conditions and cultural nuances. During this visit, GSD and Unimet students jointly participated in what designers call “charrettes” (intensive group brainstorming sessions over maps and tracing paper) providing them a first opportunity to work together. Carried away by their passionate advocacy for different approaches, the students used a combination of drawing, sign language, and the limited knowledge of each other’s languages to overcome the language barrier. They became a flawlessly integrated team—staking out initial hypotheses, and identifying particular themes to be addressed in more detail later in the studio.

The students then carried out detailed site analyses, focusing on characteristics such as local history, geography, urban structure, and relevant precedents. From these analyses another way of viewing tourism as part of the overall picture began to emerge. It challenged a number of basic assumptions:

1) That despite the presence of the international airport and the potential for an enlarged cruise port, this part of the Littoral would only be of interest to local visitors.

2) That even for locals this area would function primarily as a corridor to get to the more popular beaches to the east.

3) That the model for more effective tourism was the self-contained compound in which the visitors would be largely segregated from the local population.

As they became familiar with the site, the students began to uncover a series of latent potentials that could be tapped to advance another very different model.

The 16th century Spanish colonial town, La Guaira, and its three imposing forts remained intact although damaged by the floods. These forts link to the original Spanish trail over the Avila Mountain to Caracas. A skillful strategy of restoration, adaptive re-use, and the framing of new relationships and public spaces could re-position these valuable resources as a heritage site of international importance, similar to Viejo San Juan, Cartagena, and Havana Vieja.

Similarly the extraordinary Avila National Park rising abruptly from the coast, coupled with the need to open up “reserves” of unbuilt land along the ravines seemed to offer a great opportunity to make a virtue out of a necessity. These reserves and the upstream dams and protective measures to open up the watercourses were the sine qua non in permitting the re-building effort to occur in the first place. The enhanced presence of nature, the students felt, could be turned into a new source of identity and an attraction, appealing to Ecotourism as well as constituting an appropriate commemoration of what had happened there.

Students perceived the opportunity to develop the cultural dimension of the Littoral, building on the patterns of local tourism and inspired by precedents seen in visits to other parts of Caracas and to Choroní, further west along the Coast. In field trips to these sites, students had become familiar with the way in which local craft and food markets, festivals, cuisine, recreation, and the appreciation of tropical architecture and landscape could all become part of a shared experience, including local tourists and residents, and allowing visitors to sample the unique features and products of the country while providing desperately needed new sources of income.

The fact that major elements of transportation infrastructure including the airport and the port both on this site and requiring significant upgrading, suggested new ways of integrating the experience of travel with visits of the area and connections to other areas. In particular the potential was seen to make connections between international air travel and short flights and cruise ships, taking advantage of the Littoral’s potential as a jumping off point for other destinations such as Margarita Island and Angel’s Falls.

The coastal main road, Avenida Soublette, required substantial re-building. This provided an opportunity to reshape it as an attractive seaside boulevard that would calm traffic and emphasize local destinations—places to stay, museums, and things to do and see—and not just to speed by. In turn, such a pleasant boulevard would allow for the redevelopment of key intersections. At these a variety of travel modes could be provided and connected, ranging from long distance buses, to local jeep service up the slopes, to water shuttles, to recreational hiking and horseback excursions, integrating daily and special use and making many local attractions, currently unknown to outsiders, more accessible.

The students took these ideas and others and worked as a team to produce a shared urban design framework for the Littoral. They made determinations about the type and scale of development appropriate for areas of the site, appropriate new uses, and formulated objectives for shaping new infrastructure. In these deliberations, we asked them to carefully balance the need for specificity, versus the need for flexibility in setting the stage for specific public and private development moves. This involved refinement and negotiation among themselves as an overall framework and common principles and guidelines were assembled.

As this work unfolded, fundamental questions arose which provided a context for addressing the role of tourism: How do we define the client for our efforts? How do we respond to the natural limits? How do we work with the informal sector? In the process of attempting answers to these questions, the opportunity for a kind of tourism in this area reflecting values that the students endorsed, became a key component of the overall strategy. Its diverse roles included a center for La Guaira – Maiquetía, a gateway to the Avila, a playground for Caracas, an enhanced Capitol for Vargas State, and a showpiece for Venezuela.

Within the shared framework, students then developed individual proposals, many of which explored themes that related to the tourism potential. Taken together they produce a mosaic of responses ranging from the very large scale of imagining the Simón Bolívar airport as a regional-hub in Latin America and as an urban core of the Littoral to the very fine grain of such projects as new piers for recreational activities and flood control mechanisms as cultural art icons.

Several aspects of this studio experience were notable. Within each component of the joint studio the range of disciplinary backgrounds and knowledge of the individual students became a positive resource encouraging crossover explorations and solutions not bounded by a single area of expertise. This blending and intertwining of collective work exposed the students to scales of intervention which closely simulate real world experience of urban design practice.

Several of the students, for example, had backgrounds in economics. They were able bring particular attention to the need to use modest levels of investment strategically in the proposals, to find local strengths and economic niches and exploit them effectively, and to devise incentives to expand on what already exists on the ground. Some of the most challenging issues in this respect involved the links and interdependencies between the formal and informal market sectors and the need to engage both.

The landscape architects led an effort to find a solution to protect green spaces, including the National Park. Recognizing that the current border of the National Park is meaningless in ecological terms, it was recommended that the existing barrios in the National Park be legitimized by passing the land to Vargas state, enabling the state to implement measures to prevent future barrio growth. In return, new National Park lands would be designated to protect the beaches east of Los Caracas and to finally connect the National Park to the Sea. In Mount Avila, the ravines would be redesigned as attractive open space for the urban areas, providing better protection from future floods and serving a variety of social functions. Public access would be maintained continuously along the coastline, allowing everyone access to the Littoral’s main asset.

An extraordinary relationship developed between the two groups, GSD and Unimet, at all levels, professional, inter-cultural, and personal. Without the hospitality and deeply generous welcome and insights of the Venezuelans, the GSD students could never have attained the level of understanding that they did of a profoundly different and stressed situation. The GSD students brought fresh eyes and enthusiasm, offering some ways for the Venezuelans to see the familiar in a new light.

A key lesson learned from this joint investigation is that ideally tourism does not function as a stand-alone activity. Rather it operates as an added capacity built into the mix and fabric of a place at many levels, making it hospitable and accessible, adding cultural richness, and bringing economic benefit, without major disruptions to local patterns.

Ken Greenberg was a Visiting Critic Spring Term 2000 at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. As Principal of Greenberg Consultants Ltd., based in Toronto, he has played a leading role on a broad range of urban design assignments in highly diverse urban settings in his own city of Toronto and in such cities as Amsterdam, Paris, Montreal, and San Juan, Puerto Rico. His recent projects include the award-winning Saint Paul on the Mississippi Development Framework, the Master Plan for the Brooklyn Bridge Park on the East River in New York, and plans for the North Delaware River in Philadelphia.

Students

GSD:

Andrea Korber

Anne Wilkerson

Christopher Mathews

Frank Ruchala

Jamie Phillips

Kayako Nakanishi

Kevin Benham

Krista Benson

Lisa Chung

Pablo Allard

Takame Matsushima

Trina Gunther

Unimet:

Amalia Borrajo

Gabriela San Claudio

Nataly Haratz

Rafael Canelon

Rafael Vallario

Roxana Acevedo

Sete Bentata

Teresa Montesano

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Tourism

Ellen Schneider’s description of Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega in her provocative article on Nicaraguan democracy sent me scurrying to my oversized scrapbooks of newspaper articles. I wanted to show her that rather than being perceived as a caudillo

Recreating Chican@ Enclaves

Centrally located between southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, is a hundred-mile long by seventy-mile wide intermountain basin known as the San Luis Valley. Surrounded on the east …

Tourist Photography’s Fictional Conquest

Recently, while walking across the Harvard campus, I was stopped by two tourists with a camera. They asked me if I would take a picture of them beside the words “HARVARD LAW SCHOOL,” …