A Review of Sonorous Worlds: Musical Enchantment in Venezuela

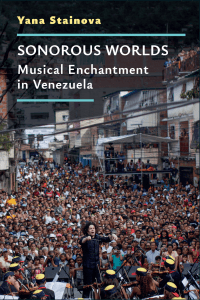

Sonorous Worlds: Musical Enchantment in Venezuela by Yana Stainova (University of Michigan Press, 2021, 265 pp.)

Sonorous Worlds is anthropologist Yana Stainova’s memoir (not her term) of her experiences while researching music among marginalized communities in Venezuela.

To be clear, by “music” she means European, not Afro-Venezuelan, music. Her research took place within the framework of El Sistema, the nationwide free classical-music education and performance network founded in 1975 by José Antonio Abreu (1939-2018). El Sistema has trained hundreds of thousands of young people to play instruments and has inspired similar programs in dozens of countries. Over the years, El Sistema was supported by the various changing administrations of Venezuela, but it reached a new level of state patronage after Hugo Chávez became president in 1999.

Stainova, who is Bulgarian, recalls her earliest childhood memories of crowds demanding the “fall of communism in Eastern Europe,” and she’s thoroughly skeptical about the Venezuelan government and its propaganda, but that’s not her focus. Instead, she explores how the act of making music together connects her with the Venezuelan musicians whose lives El Sistema regulates, and with whom she feels solidarity. The arc beneath her narrative, however, is the ongoing deterioration of public and political order in Venezuela.

In the International Orbit

El Sistema’s thrilling orchestral concerts received enthusiastic international attention in the first decade of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, launching the meteoric success of the youthful and charismatic conductor Gustavo Dudamel (b. 1981), an alumnus of the system. Today Dudamel is a superstar, concurrently directing the Orquesta sinfónica Simón Bolívar in Caracas, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and, now, the Opéra national de Paris. Other graduates of El Sistema hold posts in orchestras around the United States and internationally.

There is a critique to be made of the El Sistema performance esthetic: that the passion is too studied, with too much big-and-loud and a penchant for spectacle that strays into the bombastic, especially when folded in with the nationalism of its politicized patron. But it seems undeniable that the Sistema orchestras (there are several, with different names) brought a style.

That style, at its best, surely has much to do with the sensibility the Venezuelan musicians bring to it. Like musicians in other Afro-Latin American countries, El Sistema musicians grow up absorbing from home, street and media different vernacular music traditions and different senses of expression, corporeality, collectivity, movement and performance than have historically prevailed in European symphony orchestras.

Significantly, I would argue, they bring a heightened sense of time-flow. If you’ve never heard a maraca player take a solo, you haven’t been to Venezuela. Conductor-led time is always a negotiation between conductor and ensemble, and the evidence from recordings suggests that musicians in the Simón Bolívar orchestra excel at feeling the time together, precisely. With temporal acuity come acoustic phenomena; timbres fuse in mid-air if two instruments are exactly in tune and exactly in time, which in turn throws harmonic rhythm into relief. The Bolívar players’ sharp sense of rhythm, coupled with grueling extended rehearsals (in a way not possible with U.S. or European orchestra players, who have unions to protect them), forged an identifiable sound that excited the classical-music world. Along with that, in marked contrast to the normal symphonic deadpan, the young players were openly enthusiastic about the music, and even moved their bodies.

Alternative Narratives

“Classical” music (a term I find unhelpful) has much to offer, including an intricate and proven pedagogy, a centuries-deep repertoire of masterworks that repay lifelong listening, and a global support infrastructure. But the authoritarian musical command structure of the symphony orchestra is inherited from an age of monarchy and aristocracy: top-down, with the music created by the composer, realized by the conductor, and executed by players, who function in effect as the conductor’s instruments. Its applicability as a social model, especially in a postcolonial setting, is problematic.

Alberto Arvelo’s documentary Tocar y Luchar (2006) lauded the achievements of El Sistema; Stainova cites it as her introduction to this sonorous world. But El Sistema’s methods, and its political project, subsequently came under scrutiny, notably from British music educator Geoffrey Baker, who has studied music pedagogies in Cuba and Peru as well. (Disclosure: I know Baker and admire his work; I have never conversed with him about El Sistema.)

Baker was drawn to El Sistema after attending a performance by the Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra in London in 2007, but his fascination quickly turned to dismay as he traveled to Venezuela to study it. His scathing El Sistema: Orchestrating Venezuela’s Youth (Oxford, 2013) portrays Abreu as a Machiavellian tyrant, with zingers like “there were moments when researching El Sistema felt more like investigating organized crime than an arts education project.” I won’t address Baker’s dissenting critique of El Sistema in this review, as Stainova does not much engage with it, and El Sistema is the universe of her study, not her subject. But it’s lurking in the background. In a blog post written in response to a 2017 article by Stainova titled “Enchantment as Methodology,” Baker rejected her central concept: “Enchantment is the problem, not the solution,” he wrote. In response, she writes in Sonorous Worlds that Baker’s criticism “hurt me” and proposes “alternative narratives that challenge the story of disenchantment.”

Her alternative narrative employs a strategy that has been increasingly common in recent years: the metastory of fieldwork. The now-routine declaration of a scholar’s positionality seems to have broadened in recent years into a first-person genre in which the studier is an actor along with the studied.

Stainova seems to have enjoyed in Venezuela a level of musical enchantment beyond her previous experience. There, in personal revelation, her story finds its sonority. In a sonically sensual scene near the end of the book, she lies beneath a piano in Caracas, luxuriating in the harmonics ringing out of the soundboard overhead as a friend plays Scriabin (1871-1915), the mystical, synesthetic, jubilantly excessive Muscovite composer whose best-known work is The Poem of Ecstasy.

A meticulous journal-keeper, she examines micro-details of encounters with musicians and music. In the chapter “The Dictatorship of Luxury,” she goes on the road with the band, embedded in the orchestra’s charter flight to Hiroshima (of all places), Tokyo and Korea, with a stopover in Lisbon – a journey across the globe that would be unimaginable for most Venezuelans. She reports their experience of being “rich for a week” — housed and fed in luxurious conditions, far from “the shortages of milk, corn flour, and toilet paper that we had left behind in Venezuela,” and to which they would immediately return. In turn, she writes, the musicians were expected to respond with “obedience and complete availability.”

One of Stainova’s chapters concerns violence, of which there is plenty in Caracas, describing her own and others’ brushes with street crime as well as, beginning in 2014, ongoing political disturbances with concomitant rising police repression. The instruments that make the musicians potential robbery targets on the street are their vehicles for escape, mentally and even physically. In a downbeat coda set in 2018, Stainova visits some of her Venezuelan friends in their new home, Paris; having joined the expanding Venezuelan diaspora, their professional skill as musicians is now their key to survival as expatriates. In the book’s moment of resolution, they gather in an apartment, where they pull out a guitar and sing – what else? – Joseíto Fernández’s “Guantanamera,” improvising nostalgic coplas to the Cuban chestnut.

The personal joy of playing music with others, Stainova suggests, is the great good that has come from this enormous educational project. Musicologists are accustomed to dealing with parameters that are quantifiable, notatable and generally machinable, but these don’t account for what we experience from music. This reader could have done with less theorizing, but I generally appreciate her vocabulary of concepts, which include ineffability, violence, sonic citizenship and energy. (“Magic” I’m not so keen on.)

It’s not new to talk about energy; Taoists schematized it millennia ago. But Stainova is right to center it: good musicians have to be masters at working with energy. She doesn’t engage religious or spiritual issues, foregrounding instead her notion of enchantment – it sounds more natural in Spanish: encanto — which, says Stainova, is “about allowing ourselves to be changed.” As often happens with anthropologists, she seems to be a different person for having undertaken her multi-year research project. How could she not be?

“Lost in the telling of a story about the collapse of a political system in Venezuela,” she writes in conclusion, “are the stories of lives just beginning, futures unfolding.” This reader has a difficult time matching her optimism, but I’d love to be wrong.

Ned Sublette is the author of four books, including Cuba and Its Music. His film Tierra Sagrada premieres March 25, 2022 at the Big Ears Festival in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Related Articles

A Review of Negative Originals. Race and Early Photography in Colombia

Negative Originals. Race and Early Photography in Colombia is Juanita Solano Roa’s first book as sole author. An assistant professor at Bogotá’s Universidad de los Andes, she has been a leading figure in the institution’s recently founded Art History department. In 2022, she co-edited with her colleagues Olga Isabel Acosta and Natalia Lozada the innovative Historias del arte en Colombia, an ambitious and long-overdue reassessment of the country’s heterogeneous art “histories,” in the plural.

A Review of Megaprojects in Central America: Local Narratives About Development and the Good Life

What does “development” really mean when the promise of progress comes with displacement, conflict and loss of control over one’s own territory? Who defines what a better life is, and from what perspective are these definitions constructed? In Megaprojects in Central America: Local Narratives About Development and the Good Life, Katarzyna Dembicz and Ewelina Biczyńska offer a profound and necessary reflection on these questions, placing local communities that live with—and resist—the effects of megaprojects in Central America at the center of their analysis.

A Review of Authoritarian Consolidation in Times of Crisis: Venezuela under Nicolás Maduro

What happened to the exemplary democracy that characterized Venezuelan democracy from the late 1950s until the turn of the century? Once, Venezuela stood as a model of two-party competition in Latin America, devoted to civil rights and the rule of law. Even Hugo Chávez, Venezuela’s charismatic leader who arguably buried the country’s liberal democracy, sought not to destroy democracy, but to create a new “participatory” democracy, purportedly with even more citizen involvement. Yet, Nicolás Maduro, who assumed the presidency after Chávez’ death in 2013, leads a blatantly authoritarian regime, desperate to retain power.