Review of The Hispanic World and American Intellectual Life, 1820-1880

New England Bridges to the Hispanic World

The Hispanic World and American Intellectual Life, 1820-1880 By Iván Jaksić New York: Studies of the Americas, Palgrave Macmillan, 2007

Iván Jaksić’s highly original and engaging scholarship on the origins of U.S. academic interest in Ibero-America brilliantly reveals previously unknown trans-Atlantic and Western hemisphere intellectual networks. His research focuses on the life, interactions and contributions of those Jaksić calls “the pioneer American scholars and lifetime students of the Hispanic World”—Washington Irving, George Ticknor, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Mary Peabody Mann and William H. Prescott—and a raft of Hispanic intellectuals. Jaksić, a former DRCLAS Santo Domingo Visiting Scholar (1997-98) and Library Scholar, has uncovered primary material that offers fascinating new insights into the beginnings of Hispanism and Hispanic studies in the United States.

Jaksić’s book is intellectual history and biography, organized as chapters on the five main protagonists. Researched deeply and carefully, it reads as a novel set in an era when “the breakdown of the Spanish empire in the Americas, and the resulting emergence of new nations in the Western Hemisphere, presented enormous challenges and opportunities for the United States—when Americans of the early republic deliberately engaged in an effort to define their culture, history, and uniqueness as a nation” (p.1) The book is full of surprises even for experts on the American historical and literary tradition and will surely be a cornerstone for all future efforts to understand the interplay between the construction of American political culture and national identity and the formation of U.S. perceptions, attitudes, and policies toward the Hispanic world. It is impossible to disagree with the book jacket blurb by Richard L. Kagan (editor of Spain in America: The Origins of Hispanism in the United States (2002): “This is unquestionably the best study on Spain’s place in the imaginary of nineteenth century America.”

The discoveries Jaksić made in unknown, little-known and unpublished memoirs, letters, diaries and manuscripts is a tale of its own, worthy of publication as a testimony to the solitariness, tedium, disappointment and elation that come with a five-year long quest. He relentlessly tracked the lives, adventures and intellectual contributions of a small group of Americans who pioneered the serious study of Spain and Latin America in the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century. At Harvard, the Houghton Library contained a virtually unknown collection of correspondence between Longfellow and Hispanic intellectuals, unpublished Longfellow translations and evidence of a romance with the daughter of a Spanish innkeeper, Florencia González. The findings at Houghton resulted in a three-month exhibition curated by Jaksić in 2005.

At the Harvard University Archives, Jaksić also disinterred valuable materials related to the work of George Ticknor, Smith Professor of French and Spanish and a founder of Hispanic studies in the United States at Harvard (1819- 1835) and Longfellow, who succeeded Ticknor as Chair in 1836. Among the Ticknor materials, Jaksić recovered the annotated version of his course syllabus, correspondence related to instruction in literature and Spanish language with College administrators, and manuscripts with notes for the course on Spanish literature. These materials made evident not only the thinking of the country’s premier Hispanist, but also the fact that university curriculum and organizational reform were no easier in the 1820s and 1830s than they are today; fossilization in academia started early, often resisting even the most extreme efforts to inject new life and new forms.

Harvard was not the only place where Jaksić explored archives to create this intriguing story. The Real Academia de la Historia (Spain), the Massachusetts Historical Society of Boston and the Rauner Special Collections Library at Dartmouth all revealed precious secrets that contributed to this painstakingly researched book .

Each of Jaksić’s intellectual biographies is a fascinating story on its own account, intertwined in the description of previously unknown intellectual networks that reached across the Atlantic and between the southern and northern nations of the Western Hemisphere. Revelation of how the protagonists did their work, came to know one another and Hispanic colleagues, and exchanged documents by land and sea provides a colorful and humanizing lens on American and Ibero-American intellectual history in the 19th century. It also makes clear how the largely negative attitudes toward Spain and Latin America became fixed in U.S. popular and academic culture. From Prescott’s characterization of Mexicans as a “degraded race” and his claim that “fanaticism, bigotry and greed” were Spain’s legacy to Latin America to Mary Mann’s embellishment on Sarmiento’s description of caudillismo and barbarism in Argentina as the essence of Latin American politics, all the prejudicial mainstays of modern American attitudes toward Latin America come spewing forth from the Hispanist pioneers. So too do the Latin American responses as Jaksić recounts the reactions of Spanish and Latin American intellectuals, especially historians, to the work of Ticknor, Mann, and Prescott. Chilean historian Pedro Félix Vicuña (1858) even pleaded with Prescott to write a book that would “put a stop to the emerging evil” of U.S. territorial conquest, racism and interventionism in the Hemisphere (p. 158).

Jaksić concludes that the inspiration for the beginnings of “Hispanic studies” in the United States stemmed less from concern for Ibero-America itself than for the shaping of U.S. national identity. The didactic interpretation by these scholars of the rise and fall of Spanish Empire came to serve as warning of the dangers to the U.S. republic of foreign wars and incipient imperialism: “Spain was essential as a point of origin, as well as an example to be avoided, in the American search for a unique national identity” (p.4). Washington Irving even believed that “Spanish history held the key to the origins of the United States as a nation” (p. 186).

Jaksić ends his book with a masterful short account of Herman Melville’s Benito Cereno as a metaphor for the incomprehension of, and disdain for, the Hispanic world typical of popular and official America by the end of the 19th century—and to the present. Unfortunately, he does not do for Melville, and several other key characters in the narrative, what he has done for the main protagonists, leaving this reader wishing that the biographical research and intellectual history had continued still further and that a bit more explicit connections had been made to the ongoing development of the Latin American Studies and history curriculum that emerged from “borderlands studies” (most notably, Hubert Howe Bancroft) and institutionalism (most notably, Bernard Moses, at Berkeley) on the U.S. West Coast in the late nineteenth century. Perhaps this only means that Jaksić will have readers enthusiastically looking forward to the “rest of the story” when he is ready to tell it.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Dance!

We were little black cats with white whiskers and long tails. One musical number from my one and only dance performance—in the fifth grade—has always stuck in my head. It was called “Hernando’s Hideaway,” a rhythm I was told was a tango from a faraway place called Argentina.

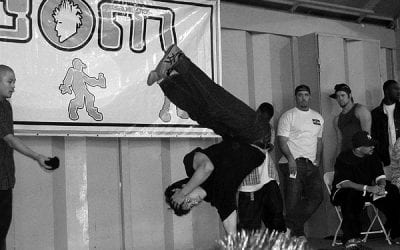

Brazilian Breakdancing

When you think about breakdancing, images of kids popping, locking, and wind-milling, hand- standing, shoulder-rolling, and hand-jumping, might come to mind. And those kids might be city kids dancing in vacant lots and playgrounds. Now, New England kids of all classes and cultures are getting a chance to practice break-dancing in their school gyms and then go learn about it in a teaching unit designed by Veronica …

Dance Revolution: Creating Global Citizens in the Favelas of Rio

Yolanda Demétrio stares out the window of our public bus in Rio de Janeiro, on our way to visit her dance colleagues at Rio’s avant-garde cultural center, Fundição Progresso. Yolanda is a 37-year-old dance teacher, homeowner, social entrepreneur and former favela (Brazilian urban shantytown) resident. She is the founder and director of Espaço Aberto (Open Space), an organization through which Yolanda has nearly …