Ronco

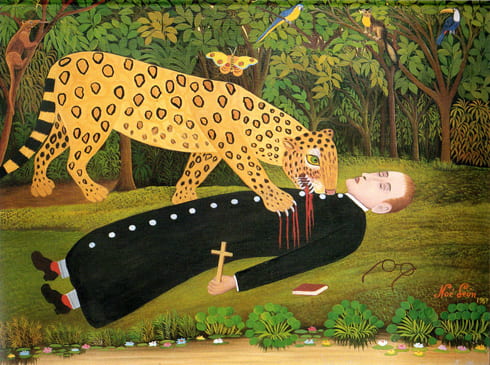

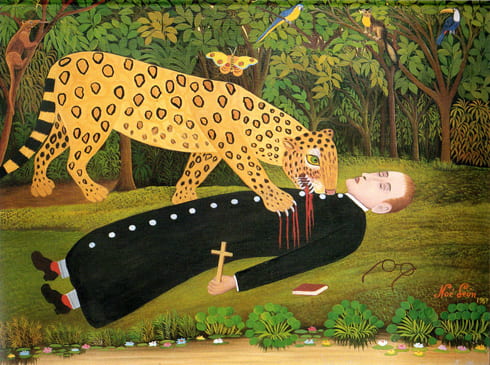

Noé León, Misionero Comido por Tigre (missionary eaten by a tiger), 1967

He wakes up suddenly, the rosettes on his back shaking as if in an earthquake. It takes him a minute to figure out where he is. It’s dark. He perks his ears and listens to the syncopated breathing of the man and the woman. He wags his tail and pulls himself under the wood. He smells the mango outside the bedroom, a rodent that scampers among the pots and pans, and the far-off water of the river that he discovered a few months back.

Before leaving the room, he arches his back and stretches his front legs as he yawns. He gets up, using his shoulder to create a space in the partially opened door and sets off toward the front exit. He wanders down the hall and catches a glimpse of himself in one of the mirrors. He jumps up to a window and opens it, pushing with his paws. Outside, he savors the air: the leaves, the feathers, the shouts.

He crosses one of the pastures. Under a full moon, the blades of grass glitter like fish scales. He sees dozens of insects—grasshoppers. moths, ants—which scamper as he approaches. He wags his tail to annoy them, his head erect, his face cold.

Photo of a jaguar by Santiago Wills

Walking slowly in the midst of the fields, his back feet falling into the footprints of his front feet, he blends into the night like a golden ghost covered with spots. He jostles straight ahead, jumping over rocks and termite nests, rolling himself into a ball to get under the barbed wire that delineates the old boundaries of his wanderings.

The cattle —that sadly prohibited prey— sleep under the ceiba trees. He steals a glance out of the corner of his eyes: black coal and maroon hulks that occasionally moo at his presence. They don’t get up and they are not scared, as they used to be a while ago, but they still feel the need to give a voice of alarm whenever they see him.

After passing a banyan tree, he turns at a relatively recent trail. He continues on, inclining himself below fallen trees and floating above piles of leaves and thorn-laden branches. His whiskers shape his path. He listens to the singing toads, the noisy explosions of the cicadas and the waters that wind down from the high part of the Sierra Nevada.

He notices the increasingly dense trees. He’s not far from the house, but he doesn’t know this area well. He wonders why he hasn’t marked it before, even though, bit by bit, he is understanding it better. There are the vacant fields where he played as a puppy, the banyan tree, which marks the entrance to the forest, and now, the jagua tree, which marks the ascent towards the mountains and ensuing descent to the valley. He hugs the trunk, supporting himself on his hind legs, and scratches it forcefully to sharpen his claws.

Photo of a jaguar by Santiago Wills

He leaves the jagua tree with deep wounds and sets off toward the river. His muscles tense, he stops for a while and lets the sounds and the smells of the jungle assault him. He listens to the falling leaves, the owl flapping its wings, and the labored breathing of the peccary. The possibility of the hunt excites him. He smells the thick nocturnal exhalation of the trees, the intoxicating stench of the peccary, and a new smell, one that’s somehow familiar.

He pulls back his upper lip, lets the air enter into his snout and draws it in forcefully. Again, he smells the odor of the peccary, but he ignores it. He’s interested in the new smell, a combination of musk, ammonia and unknown hormones. He repeats the process and feels inebriated by the perfume.

Immediately, he goes in its pursuit. He abandons the known trail and negotiates the fields hastily. He goes along the edge of a stream until he finds a place to cross it. He runs among the trees without paying any attention to the noise he is making. He stumbles on a root, but keeps on, the smell guiding him to a place in the river that he had never visited.

When he reaches the shore, he observes the churning flow, and hesitates. Trunks and branches are lost among the whirlpools and foam that dashes against the rocks. He sees a possible route, but he resists jumping. A cold wind caresses his bank and makes him shiver. He pulls his lip back to gather force and lets himself be intoxicated by the smell. Then he hears it: a growl similar to his own, but more urgent. A command that leaves him no choice.

Impassioned, he jumps. The cold water strikes him like a blow. His body sinks and, for a moment, he only sees the black vacuum that threatens to devour him. The current pushes him down the river and the water pulls him toward the bottom. He uses his paws frenetically to get out. As if he were supporting himself on firm ground, he propels himself against the water to rise to the surface. The river continues to force him down, but he manages to lift his head out of the water, breathe and reach a section of the river where he can swim with ease.

Photo of a jaguar by Santiago Wills

He hears the long deep cry once more. He feels the rocks below his paws, the wind on his soaked fur, and an overwhelming desire. He shakes himself off, sending drops of water towards the plants on the shore. He runs toward the sound, towards the smell, towards his very self.

It’s dawning when he sees her. Dazed, he confronts her with a growl. He recognizes her as a similar being, even though he only has vague memories—fleeting images, odors, tastes, textures, sounds—of his mother and dog-devoured corpse of his litter mate. She is his size or just a bit smaller. Her face is thin, graceful. She has brown eyes, like the river water during the day, nearly squared rosettes with spots on the inside of her back, and thick legs with poorly defined muscles. An L-shaped stain surrounds her left eye.

She growls at him and bears her fangs when she sees him emerge from the thicket. She surveils him, extending her right paw, claws out, and quickly swipes the air, as if challenging him to combat.

After a moment’s hesitation, he approaches. He encircles her, maintaining a prudent distance, his gaze always attentive to her claws, her jaws and the L on her left eye. He doesn’t quite know what to do. He draws near, dodges her attacks and growls over and over again, smelling her, beholding her, savoring her aroma. He discovers his fangs, moves his head from side to side, turns his ears, and drags his tail on ground whose dampness has begun to evaporate; below his face, his eyes fixed, he twists his whiskers, absorbs the golden color under the shining rosettes, and growls, at once confused and certain of himself.

He circles her, drawing closer to her claws, to her flank, to her tail, measuring each movement in the midst of his anxiety. He is scared, but it’s a strange kind of fear. It’s not the fear of being punished or the fear of pain or abandonment. This fear drives him. It makes him sweat, take a step forward and study with glee the claws that strike the air only a few inches from his nose.

His senses are dulled and at the same time, they are more alert than ever. For the first time, he does not smell the jungle, only the amalgam of odors emitted by the body in front of him. He can distinguish the smell of the dry blood of a deer on her face, the acrid perfume of vaginal fluids, the pus of an unhealed wound on her back leg. He listens to the sharp tone of her growls, the less violent snorts, the muscles below her skin. He feels how his back is heating up, the black spaces that absorb the golden light, and the dark mud hardening under the pads of his paws.

The ritual continues for a while. Finally, he waits for an attack and lunges at her paws, while dodging it. He rolls on his back with his two front legs joined in the air like a mantis. And there’s a change. The snorts stop, the claws are drawn in and she turns her back.

He stops and slowly approaches her, his tail between his legs. He feels the heat of desire, the anxiety of closeness and a sudden discomfort. Frozen, he watches her.

It takes him a while to figure out what’s wrong. He sees her turn her face and growl, but he keeps still. A familiar sound bothers him. His ears perk up to hear it better.

The timbre of the man’s voice. He hears it regardless of the distance. In spite of everything, he concentrates on the echo that the air brings over from the other side of the river. He hears the tones that form his name.

Wavering, he looks at her anew. She is still on the ground with her eyes nailed to his, commanding him. He takes a step forward, conscious of what he should do. He growls. He devours her taste, her aroma, her body and falters one last time.

Tense, he contemplates her before turning his face and running toward the river, the forest, the vacant fields and the voice that follows him ever since he can remember.

Ronco

by Santiago Wills

Noé León, Misionero Comido por Tigre (missionary eaten by a tiger), 1967

Despierta de golpe, las rosetas en su lomo agitándose como si el mundo temblara. Tarda un momento en darse cuenta del lugar en el que se halla. Está oscuro. Tuerce las orejas y escucha el respirar sincopado del hombre y la mujer. Mueve la cola de lado a lado y se arrastra bajo la madera. Huele el mango fuera de la habitación, un roedor que se escabulle entre las ollas y el agua lejana del río que descubrió hace un par de meses.

Antes de abandonar el cuarto, arquea la espalda y estira las patas delanteras al tiempo que bosteza. Se levanta, usa el hombro para abrirse un espacio por la puerta entreabierta y enfila hacia la salida de la casa. Recorre el pasillo y vislumbra su reflejo en uno de los vidrios. Salta por una ventana que abre empujando con sus almohadillas.

Ya afuera saborea el aire: las hojas, las plumas, los gritos.

Atraviesa uno de los potreros. Bajo la luna llena, las briznas fulguran como las escamas de un pez. Observa decenas de insectos —saltamontes, polillas, hormigas— que se esconden conforme se acerca. Sacude la cola para molestarlos, la cabeza erguida, el rostro helado.

Camina lentamente, las patas traseras ocupando las huellas de las delanteras, un espectro dorado cubierto de manchas que se confunde con la noche en medio del pastizal. Avanza en línea recta, saltando sobre rocas y termiteros, y encogiéndose bajo los alambres de púas que demarcan las antiguas fronteras de sus andanzas.

Foto de un jaguar por Santiago Wills

El ganado —esa presa tristemente prohibida— duerme bajo las ceibas. Lo observa de reojo: bultos carbones y granate que de vez en cuando mugen en respuesta a su presencia. No se paran ni se asustan, como solían hacerlo tiempo atrás, pero todavía sienten la necesidad de dar una voz de alarma cada vez que lo ven.

Después de pasar junto a un higuerón, dobla por una trocha relativamente reciente. Continúa, inclinándose bajo árboles caídos y flotando sobre hojarascas y ramas cargadas de espinas. Sus bigotes dan forma a su andar. Escucha el canto de los sapos, las explosiones de las chicharras y las aguas que descienden sinuosas desde la parte alta de la sierra.

Foto de un jaguar por Santiago Wills

Observa los árboles que van cerrándose. A pesar de no haberse alejado demasiado de la casa, no conoce muy bien esta zona. Se sorprende de no haberla delimitado antes, aunque, poco a poco, la entiende mejor. Están los potreros, donde jugaba de cachorro, el higuerón, que marca el giro hacia el bosque, y ahora la jagua, que indica el ascenso hacia las montañas y luego el descenso hacia valle. Abraza el tronco apoyándose sobre sus patas traseras y rasguña con fuerza la corteza para afilar sus garras.

Deja la jagua con heridas profundas y se encamina hacia el río. Los músculos tensos, se detiene tras un centenar de metros y deja que los sonidos y los olores de la selva lo asalten. Escucha el caer de las hojas, el aleteo de una lechuza y la respiración febril de un pecarí cercano. La posibilidad de la caza lo emociona. Huele la espesa exhalación nocturna de los árboles, el hedor embriagante del pecarí y un olor nuevo, que sin embargo le resulta familiar.

Retrae el labio superior, deja que el aire entre a su hocico y lo aspira con fuerza. De nuevo, siente el aroma del pecarí, pero lo ignora. Le interesa el olor nuevo, una combinación de almizcle, amoníaco y hormonas desconocidas. Repite el proceso y se embriaga concentrándose en el perfume.

De inmediato, lo persigue. Abandona la trocha conocida y atraviesa los rastrojos cada vez con más afán. Bordea un caño hasta encontrar un lugar por donde pasar. Trota entre los árboles sin reparar en el ruido que hace. Tropieza con una raíz, pero sigue adelante, el olor guiándolo hacia un lugar del río que nunca ha visitado.

Al llegar a la orilla, observa el caudal bruñido y por un momento duda. Troncos y ramas se pierden entre remolinos y espumas que chocan con las rocas. Ve la posible ruta, pero se resiste a saltar. Un viento frío acaricia su lomo y lo hace temblar. Retrae nuevamente el labio para tomar fuerzas y se deja embriagar por el olor. Entonces lo escucha: un rugido similar al suyo, pero más apremiante. Una orden que le quita cualquier opción.

Salta enardecido. El agua gélida se siente como un golpe. Su cuerpo se hunde y, por un momento, ve sólo el negro que amenaza con devorarlo. La corriente lo empuja río abajo y el agua lo hala hacia el fondo. Usa sus patas con frenesí para salir. Como si estuviera apoyándose en tierra firme, se empuja con el agua para salir a la superficie. El río lo empuja, pero luego de un esfuerzo saca la cabeza, respira y alcanza un sector donde puede nadar con tranquilidad.

Foto de un jaguar por Santiago Wills

Escucha nuevamente el rugido. Siente las piedras bajo sus almohadillas, el viento sobre su pelaje empapado y un deseo que lo consume. Se sacude de lado a lado, lanzando gotas de agua hacia las plantas en la orilla. Corre hacia el sonido, hacia el olor, hacia sí mismo.

Empieza a clarear cuando la ve. Embriagado, la enfrenta con un gruñido. La reconoce como una semejante, a pesar de que solo conserva vagos recuerdos —fugaces imágenes, olores, sabores, texturas, sonidos— de su madre y el cadáver devorado por perros de su compañera de camada. Tiene su tamaño o quizás sea un poco más pequeña. Su rostro es delgado, grácil. Tiene ojos marrones como el agua del río durante el día, rosetas casi cuadradas con puntos en sus interiores en el costado y unas piernas gruesas de músculos poco definidos. Una mancha en forma de L rodea su ojo izquierdo.

Le gruñe y le enseña los colmillos al verlo salir de la espesura. Lo vigila con agresividad, la pata derecha extendida, las garras afuera. Araña veloz el aire, como si estuviese retándolo a un combate.

Tras un momento de duda, se acerca. La rodea guardando una distancia prudente, su mirada siempre atenta a sus garras, sus fauces y la L en el ojo izquierdo. No sabe bien qué hacer. Se le acerca, esquiva sus ataques y ruge una y otra vez, oliéndola, buscándola, saboreando su aroma. Descubre sus colmillos, mueve la cabeza de lado a lado, entorna las orejas, arrastra la cola por un suelo cuya humedad comienza a evaporarse, baja su rostro, los ojos fijos, tuerce los bigotes, absorbe el color áureo bajo el brillo de las rosetas, y gruñe, confundido y al tiempo seguro.

Da vueltas a su alrededor, cada vez más cerca de sus garras, de su flanco, de su cola, midiendo cada movimiento en medio de la ansiedad. Siente temor, pero es un temor extraño. No se trata del temor al castigo o del temor al dolor o al abandono. Lo impulsa. Lo hace sudar, dar un paso al frente, estudiar con júbilo las garras que rozan el aire a escasos centímetros de su nariz.

Sus sentidos se nublan y al mismo tiempo están más alerta que nunca. Por primera vez, no huele la selva, solo la amalgama de aromas que expide cada parte de ese cuerpo frente al suyo. Puede diferenciar el olor de la sangre seca de un venado en su rostro, el perfume acre de fluidos vaginales, el pus de una herida en su pierna trasera que aún no termina de sanar. Escucha el tono agudo de sus gruñidos, los bufidos menos violentos, los músculos bajo la piel. Siente cómo se calienta su lomo, los espacios negros que absorben la luz blanca-amarilla y el barro oscuro que se endurece bajo sus almohadillas.

Sigue el ritual durante un tiempo. Finalmente, aguarda un ataque y se lanza a sus pies mientras lo esquiva. Rueda sobre su espalda con las dos patas delanteras unidas como una mantis. Y se produce un cambio. Los bufidos se detienen, las garras se esconden y le da la espalda.

Se para y se aproxima lentamente, la cola entre sus patas. Siente el calor del deseo, las ansias de su cercanía y una repentina incomodidad. La observa congelado durante un momento.

Tarda en darse cuenta de lo que está mal. La ve girar el rostro y gruñir, pero se queda quieto. Un sonido familiar lo molesta. Sus orejas se tuercen para enfocarlo. Distingue, muy lejos, el timbre del grito del hombre. Pese a todo, se concentra en el eco que trae el aire desde el otro lado del río. Alcanza a identificar los tonos que componen su nombre.

Duda. La mira nuevamente. Sigue en el suelo con los ojos clavados en los suyos, reclamándolo. Da un paso tentativo hacia adelante, consciente de lo que debe hacer. Gruñe. Devora su sabor, su aroma, su cuerpo y se debate una última vez.

Tieso, la contempla antes de girar su rostro y correr hacia el río, el bosque, los potreros y la voz que lo persigue desde que tiene memoria.

Santiago Wills (1988) is a Colombian writer. His nonfiction stories have appeared in The Atlantic, Guernica, Gatopardo, El Malpensante, and several other publications. Jaguar (Random House Colombia, 2022), his first novel, was longlisted for the Herralde Prize. Ronco is one of the novel’s main characters.

This short story first appeared in Spanish in Puñalada Trapera 2, a collection of short stories by Colombian writers published by Rey Naranjo.

For Sara Jaramillo.

Santiago Wills (1988) es un escritor colombiano. Sus historias de no ficción se han publicado en The Atlantic, Guernica, Gatopardo, El Malpensante, y otras revistas y periódicos. Jaguar (Random House Colombia, 2022), su primera novela, fue semifinalista del Premio Herralde. Ronco es uno de los protagonistas de la novela.

Este cuento se publicó originalmente en español en Puñalada Trapera 2, una antología de cuentos colombiana publicada por la Rey Naranjo.

Para Sara Jaramillo.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter – Animals

Editor's LetterANIMALS! From the rainforests of Brazil to the crowded streets of Mexico City, animals are integral to life in Latin America and the Caribbean. During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns, people throughout the region turned to pets for...

Where the Wild Things Aren’t Species Loss and Capitalisms in Latin America Since 1800

Five mass extinction events and several smaller crises have taken place throughout the 600 million years that complex life has existed on earth.

A Review of Memory Art in the Contemporary World: Confronting Violence in the Global South by Andreas Huyssen

I live in a country where the past is part of the present. Not only because films such as “Argentina 1985,” now nominated for an Oscar for best foreign film, recall the trial of the military juntas…