Self-translating Dizhsa:

Zapotec literature – by who and for who?

In my experience as a Zapotec writer, translator, speaker and activist in the Zapotec diasporic context, I have been working to write and maintain my Indigenous language in the United States. My continual connection with my community of origin over the more than 20 years of this work, allows me to be a bi-national, multilingual, and multicultural writer.

When I was 16 years old, with only an elementary school education, I migrated to the United States, speaking primarily Dizhsa. Within three years of arriving, I started to learn English and later, I improved my Spanish. Neither Spanish nor English are native languages to me. Dizhsa is a Zapotec language, spoken in the pueblo of San Lucas Quiaviní, in the Valley of Oaxaca, Mexico and in various areas in the United States, especially in Los Angeles, California.

My work on Dizhsa from San Lucas Quiaviní dates back to 1992 when I started working with linguists at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and other members of my pueblo on both sides of the border on a documentation, maintenance, and revitalization project on my language. In 1999 we published a trilingual dictionary on my language (Munro, Pamela and Felipe H. Lopez, with Rodrigo Gracia and Olivia Mendez. 1999. Di’csyonaary X:tèe’n Dìi’zh Sah Sann Luu’c (San Lucas Quiaviní Zapotec Dictionary / Diccionario Zapoteco de San Lucas Quiaviní), Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center). Completing this project gave me a new starting point, which allowed me to move beyond the preliminary questions of designing an orthography and motivated me to write in my own language and through that, to decolonize my thinking. Eight years after that, we published a four volume set of pedagogical materials to teach Dizhsa at the college level, which today is now available as in a new open access digital edition (Munro, Pamela, Brook Danielle Lillehaugen, Felipe H. Lopez, Brynn Paul, and Lillian Leibovich. 2022. Cali Chiu? A Course in Valley Zapotec, 3rd edition. Haverford: Haverford College Libraries Open Educational Resources. Online: https://oer.haverford.edu/cali-chiu/).

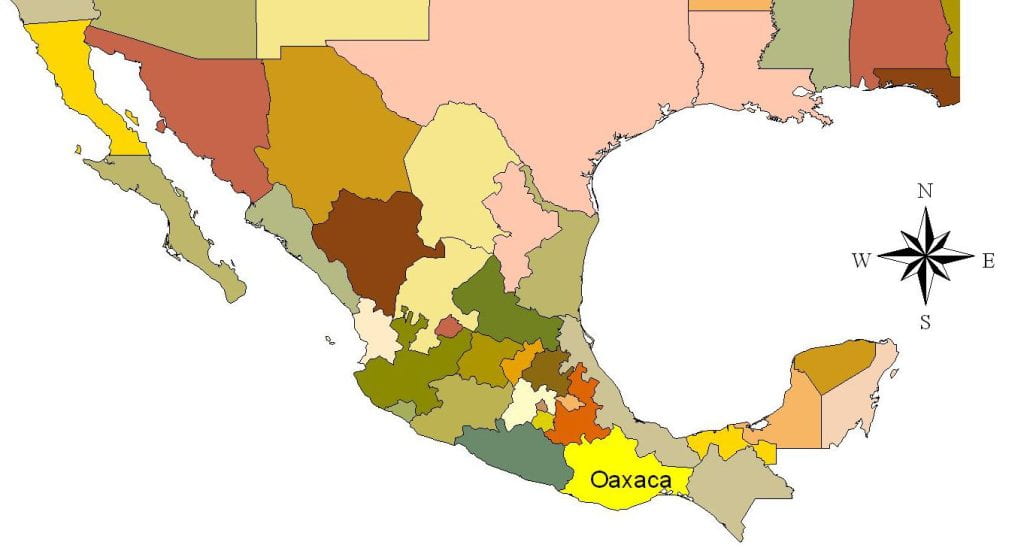

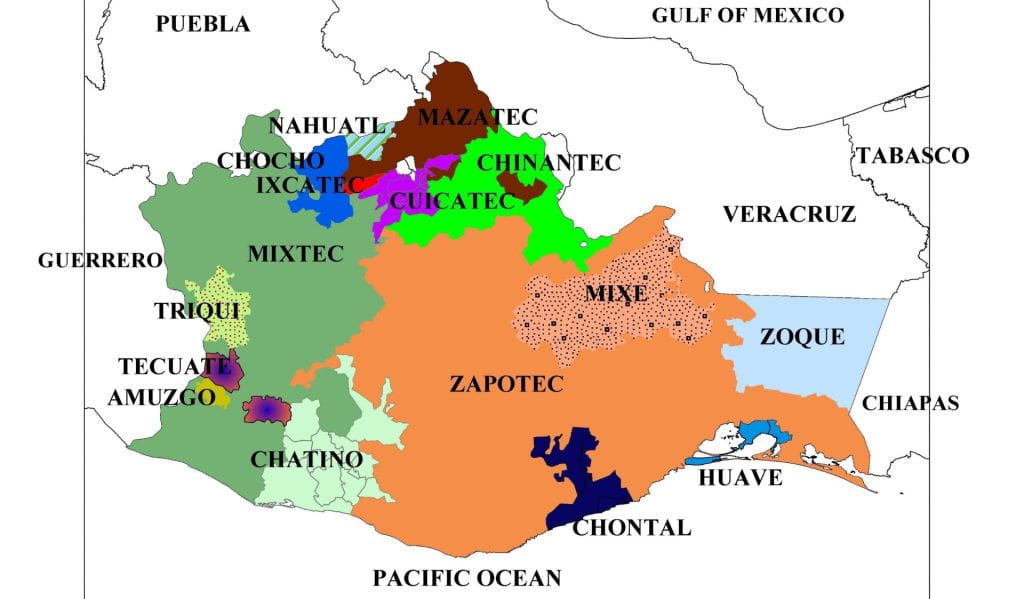

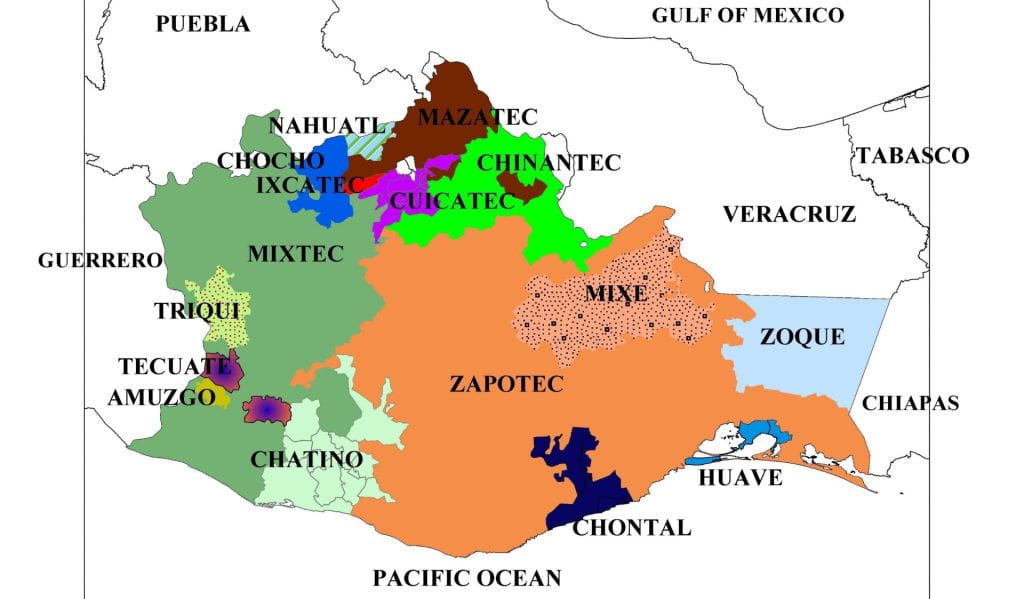

My language, Dizhsa (of San Lucas Quiaviní), is only one of the more than 40 languages in the Zapotec language family, which consists of a surprisingly large number of varieties, which are not always mutually intelligible. There are nearly half a million speakers of Zapotec languages in the state of Oaxaca and even more in the diaspora, both within and beyond Mexico.

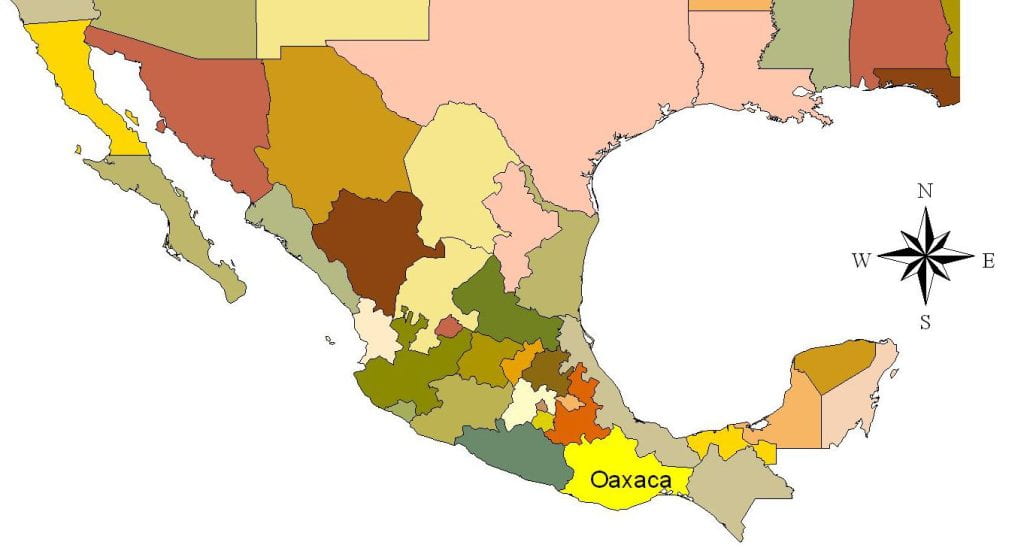

Map of Mexico.

Groups of indigenous languages in Oaxaca. Map by Felipe H. Lopez.

The challenge of writing an Ingenious Mexican language in the United States is double, given that Dizhsa not only is a minoritized language in relation to English, but also in relation to Spanish. Writing in Dizhsa for me, then, is linguistic resistance times two. Writing in our Indigenous languages is also a form of social, cultural, and political resistance because it goes against the misconception that Indigenous languages are frozen in space and time: i.e. that Indigenous languages are “traditional” and have no use outside of the community. At the same time, Spanish and English are viewed as modern languages with social and economic opportunities. These ideologies are born from and continue to flourish in a context of power imbalance that dates back to the invasion of the Spanish. In reality, Indigenous languages are flexible and adaptable to change over time, like any other language, and they are not frozen in time or space—and certainly are not “ancient” or “just dialects”. When I tweet in Dizhsa, when I talk about politics in Dizhsa, when I write poetry about my transnational life in Dizhsa, I use a modern, living language to do so!

With globalization, many Indigenous Mexicans move along with the movements of cultural, social, and economic globalization though migration and write in their languages from the context of their lived reality. This is but one reason that Indigenous writers don’t only write about our customs and traditions, but also about our lived reality. For example, two of the most prominent Zapotec poets, Irma Pineda and Natalia Toledo, address both their local identities as well as univerisal themes in their poetry. Irma Pineda’s work “Seven Poems on Migration” (Wendy Call (trans) and Irma Pineda. 2020, in Native American and Indigenous Studies) addresses questions of migration. Calls for poetry in Indigenous languages (e.g. in national or local competitions) that limit the themes to “tradition and culture” represent neither the realities nor the possibilities of Indigenous language poetry.

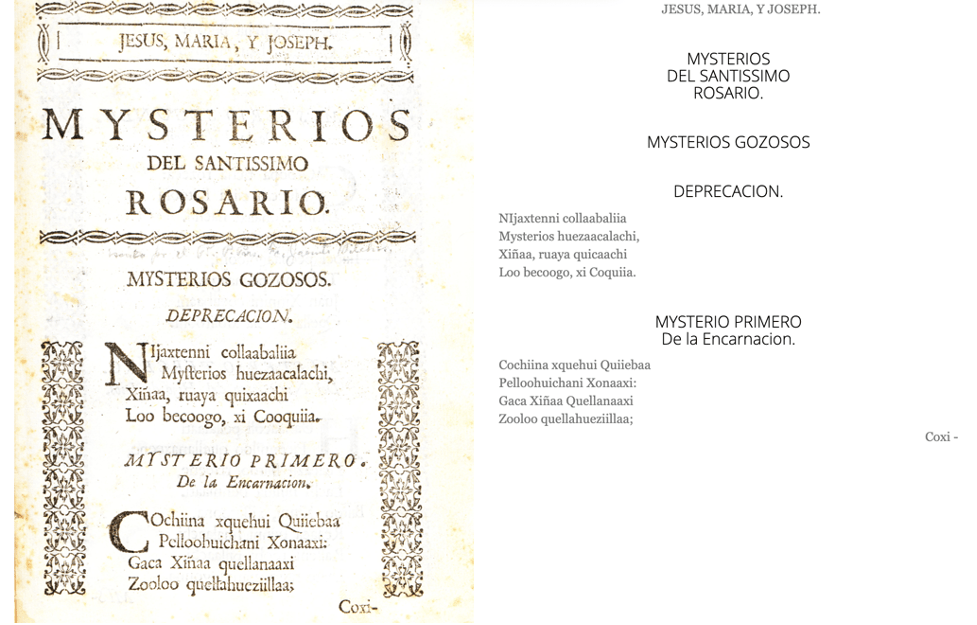

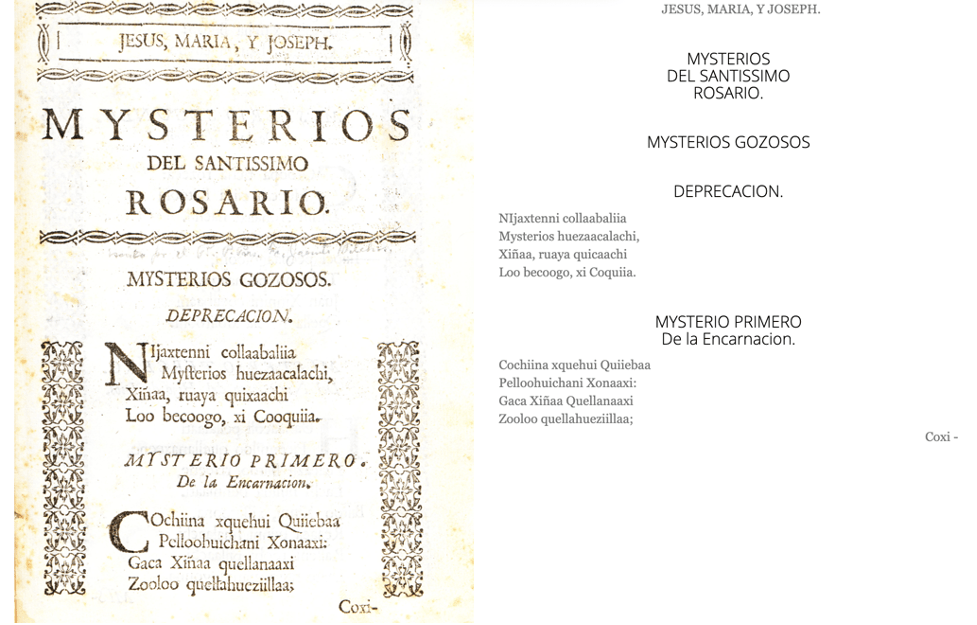

Moreover, we must disabuse ourselves of the generally accepted believe that Mesoamerican Indigenous languages are all oral languages. Zapotec languages have been written for over 2,500 years. Zapotec people have been writing their language since before the Spanish arrived! When the Spanish arrived with alphabetic technology, the Zapotec elite immediately saw the value of it and started using it to maintain their socioeconomic power and protect their land, leaving hundreds of documents written in Zapotec during the colonial period. (Some of these manuscripts are available to consult online through the Ticha Project.). These documents provide us evidence that individuals took their own initiative to write in their language. For example, we can find Valley Zapotec poems in the archive. This Zapotec poetry, which deals with the Most Holy Rosary, was first published in 1731 in a translation of a catechism. In Figure 1, you can see an image of these poems in the second edition of the catechism.

Figure 1. Zapotec poems in the second edition of Levanto’s Catechism (1766)

Recently, we can appreciate a re-emergence of contemporary Zapotec literature with an impressive trajectory that stated at the end of the 19 century. For example, we find binnizá (Isthmus Zapotec) writer Arcadio G. Molina with his Zapotec and Spanish language works, such as his book Las rosas del amor (1894). The Zapotec intellectual Víctor de la Cruz, wrote in Guie’ sti’ diidxazá. La flor de la palabra (2013), “In contrast to the Nahuas and the Mayas, who had those who compiled some of their pre-Hispanic literature and recently resumed literary creation in their language, the Isthmus Zapotec, since the end of last century, and for the most part throughout the present century, have developed and strengthened an Indigenous literature without parallel, at least within Mesoamerica.” Today we find not only Zapotec literature in Diidxazá but also in other Zapotec languages. For example, in Dilla Xhon of the Northern Sierra, with writers like Javier Castellan (Yojovi) and Mario Molina Cruz (Yalalag). In Southern Sierra Zapotec languages, we find writer Peregrino José Ruíz, winner of the 2011 CaSa prize for Zapotec poetry. In regards to the Valley of Oaxaca, we have Eleazar García Ortega, winner of the 2013 Casa prize for Zapotec narratives, as well as a youth literary collective in Quiaviní (Chávez Peón y López Reyes, 2009). Despite this broad and rich practice of writing Zapotec literature, we remain dependent on translation to visibilize our work.

Writing in Dizhsa, for me, is an initiative of to self-representation, of both my culture and my own Zapotec identity. Nevertheless, to communicate that externally, I must self-translate my work into English or Spanish. My primary concern in writing is to communicate my feelings in Dizhsa clearly. My priority in translating is to convey the intimacy of my thoughts to the reader in both English and Spanish in a way that reflects the Zapotec perspective as closely as possible, without privileging having to “write beautifully” in English or Spanish.

Knowing a language of European origin does not mean that translating is a simple question of moving from one language to another, but rather one must look for implicit and explicit concepts that bring the readers closer to the meaning. There can be gaps of cultural complexities, social relations, and linguistic gaps in the translations. In terms of the latter, we know that not all poetry needs to rhyme, of course, but if a poet wants to employ rhyme and meter in Spanish, for example, it’s fairly straightforward how to do so. Zapotec languages, however, are very different in that they are tone languages. My language, for example, has at least five contrasting tones and together with other features like breathiness and creakiness, can great more than twenty types of syllables. Creating a poem that rhymes, then, is not necessarily very interesting aesthetically, because the language provides other ways of creating beauty with words. Beautiful Zapotec poetry does not have to look the same as beautiful Spanish poetry. This holds true even more in translation—all of this tonal richness cannot be appreciated in the translation. This is the root of an important question I have for critics who are not speakers of the languages whose literature they critique: which text are you working from? This points out the necessity to have more literary critics who speak Indigenous languages, in order to have a better appreciation of not only Zapotec literature, but Mesoamerican literature more broadly.

The challenges of translation also include finding venues to publish. “Indigenous” literature is segregated within Mexican literature, marginalized—and it is very rare for it to be published without a Spanish or English translation. Because of this, we are pressed into being not only writers but also translators and the translation of our own work usually falls to us ourselves. Even though many Indigenous languages in Mexico have a large number of speakers, there are few specialized translators, in great contrast to other non-Indigenous languages where one can find dedicated literary translators.

The very act of using a colonial language to share our work in our Native languages conflict of historical power dynamics, given the context, especially between Spanish as a hegemonic colonial language and Indigenous languages as subordinate. Given this, there is a latent tension in Native literature in translation. The power relation continues today in the literary world in that authors who write in Indigenous languages must translate their work into a colonial language in order to give their work visibility.

I do translate my Dizhsa poetry into Spanish and English—why? and for who? As I laid out above, the translation is defective: the language of Dizhsa itself communicates ideologies that are not necessarily compatible with European languages and there are aspects of verbal art which don’t survive translation. But out self-translation provide us spaces where we can negotiate the ways we present our own knowledge. As long as you can’t read Dizhsa well enough to enjoy the poem in its original form, I can provide a translation, which is only an approximation– created based on my own priorities and in my own words—to allow you to appreciate (even a little) the power of Zapotec poetry—for you and for me.

Auto-traducción de dizhsa

¿la literatura zapoteca por quién, para quién?

Por Felipe H. Lopez

En mi experiencia como escritor, traductor, hablante y activista del idioma dizhsa, en un contexto de la diáspora zapoteca, he estado haciendo el esfuerzo de escribir y preservar mi lengua originaria en los Estados Unidos. Mi constante conexión con mi comunidad de origen en mi trabajo de más de 20 años me permite ser un escritor binacional, multilingüe, y multicultural.

A la edad de los 16 años con sólo la primaria, migré a Estados Unidos hablando mayormente dizhsa. A tres años de mi llegada, empecé a aprender el inglés y más tarde mejoré mi español. Por consiguiente, ni el español ni el inglés son mis lenguas nativas. Dizhsa es una variante del zapoteco del valle de Oaxaca, México, que se habla en el pueblo de San Lucas Quiaviní, y en varios estados en Estados Unidos, pero especialmente en Los Ángeles, California.

Mi trabajo en dizhsa de la comunidad de San Lucas Quiaviní data desde 1992 con un trabajo de recuperación, documentación y mantenimiento de mi lengua en conjunto con lingüistas en la Universidad de California en Los Ángeles (UCLA) y otros miembros de mi pueblo en ambos lados de la frontera. En 1999 publicamos un diccionario trilingüe (Munro, Pamela y Felipe H. Lopez, con Rodrigo Gracia & Olivia Mendez. 1999. Di’csyonaary X:tèe’n Dìi’zh Sah Sann Luu’c (San Lucas Quiaviní Zapotec Dictionary / Diccionario Zapoteco de San Lucas Quiaviní). Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center). Esta iniciativa marcó una pauta para seguir más allá de una ortografía y motivarme a escribir en mi propia lengua descolonizando así mi pensamiento. Ocho años después, publicamos cuatro tomos de material didáctico para la enseñanza de dizhsa a nivel superior, que hoy en día está disponible en acceso abierto (Munro, Pamela, Brook Danielle Lillehaugen, Felipe H. Lopez, Brynn Paul, and Lillian Leibovich. 2022. Cali Chiu? A Course in Valley Zapotec, 3rd edition. Haverford: Haverford College Libraries Open Educational Resources. Online: https://oer.haverford.edu/cali-chiu/).

Mi lengua, dizhsa (de San Lucas Quiaviní) es solo una de las más de 40 lenguas en la familia de lenguas zapotecas, que consiste de un gran número de variantes lingüísticas que no siempre son mutuamente inteligibles. Hay casi medio millón de hablantes de lenguas zapotecas en el estado de Oaxaca y aún más en la diáspora tanto en la república mexicana como en el extranjero.

Mapa de México.

Grupos de lenguas indígenas de Oaxaca. Mapa hecho por Felipe H. Lopez

El desafío en escribir una lengua originaria de México en Estados Unidos, es un doble reto ya que dizhsa no sólo es una lengua minoritaria vis-à-vis el inglés, sino también minoritaria ante el español. Entonces, escribir en dizhsa es una doble resistencia lingüística para mi. Escribir en nuestras lenguas originarias también es un semblante de resistencia política, social y culturalporque va en contra de la mis-concepción que las lenguas originarias son congeladas en tiempo y espacio: o sea que las lenguas originarias son “tradicionales” y que el uso no puede ir más allá de las comunidades indígenas. Por otro lado, se piensa que el español o inglés son lenguas modernas con oportunidades económicas y sociales. Estas ideologías nacen y continúan vigentes en una relación desigual de poder desde la invasión española. Contrario a este concepto, las lenguas originarias son flexibles y adaptables a los cambios de tiempos como cualquier otra lengua y no están congeladas ni en tiempo ni espacio y de ninguna manera son “antiguas”, ni mucho menos “dialectos”. Cuando tuiteo en dizhsa, cuando hablo de cuestiones políticas en dizhsa, y cuando escribo poesías sobre mi vida transnacional en dizhsa, ¡uso una lengua contemporánea y viva!

Con la globalización, muchos indígenas de México se mueven al contorno de los movimientos económicos, sociales y culturales globalizados, a través de la migración y escriben en sus lenguas en contextos de sus vidas cotidianas. Por eso, los escritores indígenas no necesariamente escribimos sólo sobre cuestiones de nuestras costumbres y tradiciones, sino también de nuestro propio entorno de vivencias reales. Por ejemplo, dos de las más destacadas poetisas zapotecas, Irma Pineda y Natalia Toledo, sus poesías hablan tanto de sus identidades locales como de temas universales. Por ejemplo, Irma Pineda en su obra se enfoca en cuestiones de migración (vea Wendy Call e Irma Pineda. 2020. “Seven Poems on Migration,” Native American and Indigenous Studies). Convocatorias para poesía en lenguas indígenas que limitan los temas a “tradición y cultura” no representan las realidades ni las posibilidades de la poesía en lenguas indígenas.

Además, es necesario desmitificar de la idea generalizada que las lenguas originarias de Mesoamérica son orales por excelencia. En el caso del zapoteco, ésta tiene una historia de por lo menos 2500 años en ser escrita. ¡Los zapotecos han estado escribiendo sus lenguas antes de la llegada de los castellanos! Y en la colonia, cuando los castellanos llegaron con la tecnología alfabética, la elite zapoteca inmediatamente supo del valor y la tomó para su propio uso en mantener su poder socioeconómico y salvaguardar sus tierras, dejando cientos de documentos escritos en zapoteco durante el periodo colonial. (Algunos de estos documentos están disponibles en el Proyecto Ticha.) Estos documentos nos dejan evidencias de que individuos tomaron iniciativas propias para escribir en su lengua. Por ejemplo, encontramos algunos poemas en la lengua zapoteca de los valles centrales de Oaxaca en los archivos. Esta poesía, que trata sobre el santísimo rosario, fue publicada por primera vez en 1731 en una traducción de un catecismo. En la figura 1, pueden ver la imagen de los poemas en la segunda edición del catecismo.

Figura 1. Poemas zapotecos en la segunda edición del catecismo de Levanto (1766).

Recientemente vemos la re-emergencia de una literatura zapoteca contemporánea con una gran trayectoria que inicia a fines del siglo XIX. Por ejemplo, encontramos al escritor binnizá (zapoteco del istmo), Arcadio G. Molina con algunas obras bilingües en zapoteco y español, como su libro Las rosas del amor (1894). El intelectual zapoteco Víctor de la Cruz, en Guie’ sti’ diidxazá. La flor de la palabra (2013) escribió, “Contrariamente a los nahuas y a los mayas, que tuvieron quienes recopilaron algo de su literatura prehispánica y recientemente retomaron la creación literaria en su lengua; los zapotecos del istmo, desde fines del siglo pasado, y sobre todo en el transcurso del presente, hemos desarrollado y fortalecido una literatura indígena sin paralelo en lo que fue el territorio mesoamericano, por lo menos”. Hoy en día encontramos no solamente literatura en diidxazá sino también en otras variantes del zapoteco. Por ejemplo, en dilla xhon de la Sierra Norte, con escritores como Javier Castellano (variante de Yojovi) y Mario Molina Cruz (variante de Yalalag). El zapoteco de la Sierra Sur encontramos a Peregrino José Ruíz, ganador de premios CaSa en el 2011 en la categoría de poesía. En lo que corresponde al valle de Oaxaca, Eleazar García Ortega, ganador de premios CaSa 2013 en la categoría de narrativa y un grupo de jóvenes del colectivo literario Quiaviní (Chávez Peón y López Reyes, 2009). A pesar de toda la rica tradición de la escritura y literatura de las lenguas zapotecas, seguimos dependiendo de la traducción para visibilizar nuestros trabajos.

El escribir en dizhsa para mi, es tomar una iniciativa de auto-representación a mi cultura e identidad zapoteca. Sin embargo, para comunicarlo externamente, es necesario auto-traducir mis trabajos al inglés o al castellano. Mi primera preocupación en escribir es comunicar mis sentimientos en dizhsa en una manera clara. Mi prioridad en la traducción es hacer llegar la intimidad de mi pensamiento al lector tanto en inglés como en español en una manera que refleja la perspectiva zapoteca lo más cercano posible, sin privilegiar a escribir “bonito” ni en castellanoni en inglés.

Conocer una lengua de origen europeo no significa que es una simple cuestión de mover una lengua a la otra, sino que buscar conceptos implícitos y explícitos para acercar a los lectores. Puede existir espacios vacíos de complejidades culturales, relaciones sociales y lingüísticos en las traducciones. En el tema lingüístico, sabemos que no toda poesía necesita rima, pero si un poeta quiere emplear rima y métrica en español, por ejemplo, es bastante obvio. Sin embargo las lenguas zapotecas son diferentes ya que son lenguas tonales. Mi lengua, por ejemplo, tiene por lo menos cinco tonos contrastantes y junto con otras características como aspiración y laringalización pueden crear más de veinte tipos de sílabas. Hacer un poema que rima, entonces, no es necesariamente muy interesante estéticamente, porque la lengua provee otras maneras de crear esplendor con las palabras. La belleza en las poesías zapotecas puede no parecerse igual en las poesías en castellano. Es más cuando se traducen al castellano, toda esta riqueza tonal no es apreciada en la traducción. A raíz de esto, veo la importancia de interrogar a los críticos que no son hablantes de la lengua que ellos y ellas hacen su crítica literaria, ¿sobre qué texto se basan? He aquí la necesidad de tener más críticos en lenguas originarias para tener una mejor apreciación de las literaturas no solamente de las lenguas zapotecas sino de las lenguas mesoamericanas.

Los retos de traducción incluye buscar espacios de aceptación en ser publicadas. La literatura “indígena” es segregada dentro de la literatura mexicana, orillada y al menos que sea traducida, no es usualmente publicada por sí sola. En este sentido, nos presiona a ser no solamente escritores sino también traductores. Un trabajo que muchas veces necesariamente tenemos que hacer nosotros mismos. A pesar que muchas lenguas originarias aún tienen muchos hablantes, sin embargo, a diferencia de las lenguas no indígenas en donde se puede contar con traductores especializados, éstas no cuentan con dichos traductores.

El sólo hecho de usar una lengua colonial para difundir nuestros trabajos en lenguas maternas es un conflicto histórico de lucha de poderes, dado el posicionamiento, especialmente del español como una lengua hegemónica colonial y las lenguas indígenas como lenguas subordinadas. Por consiguiente, en la literatura de los pueblos originarios y especialmente en la traducción hay una latente tensión. La relación de poder continúa en su expresión excluyente en la literatura de hoy en día con los escritores en lenguas originarias que para darle visibilidad a nuestras obras tenemos que traducirlas a una lengua colonial.

Traduzco mis poesías en dizhsa al español y al inglés, ¿pero por qué? y para quién? Como ya demostré, la traducción es una versión defectiva: la lengua dizhsa está incrustada en ideologías que no necesariamente son compatibles con las lenguas de orígenes europeas y hay aspectos del arte verbal que no sobreviven el proceso de traducción. Pero nuestras auto-traducciones nos proveen espacios que nos permiten negociar las formas que presentamos nuestros saberes. Siempre y cuando aún no puedas leer suficiente bien dizhsa y gozar el poema original, puedo proveer una traducción cual es una aproximación, hecho basado en mis propias prioridades, en mis propias palabras—para permitirte apreciar (aunque sea un poco) el poder de la poesía en dizhsa—para ti y para mí.

Felipe H. Lopez is a Zapotec writer, poet, and educator from San Lucas Quiaviní, Oaxaca. He earned his Ph.D. in urban planning from UCLA in 2007 and currently teaches in the Department of Political Science and Public Affairs at Seton Hall University. His Zapotec poetry can be found in the Latin American Literary Review, The Acentos Review and Latin American Literature Today. Felipe H. Lopez, Seton Hall University

lieb@ucla.edu

Part of this paper was presented at the LASA conference “Améfrica Ladina: Vinculando Mundos y Saberes, Tejiendo Esperanzas” in Guadalajara, 2020. I am grateful to the attendees and discussants as well as to Ignacio Carbajal and Brook Lillehaugen for their comments; all errors are mine and mine alone.

Felipe H. Lopez is a Zapotec writer, poet, and educator from San Lucas Quiaviní, Oaxaca. He earned his Ph.D. in urban planning from UCLA in 2007 and currently teaches in the Department of Political Science and Public Affairs at Seton Hall University. His Zapotec poetry can be found in the Latin American Literary Review, The Acentos Review, and Latin American Literature Today.

Email: lieb@ucla.edu

Parte de este trabajo fue presentado en el congreso “Améfrica Ladina: Vinculando Mundos y Saberes, Tejiendo Esperanzas” de LASA en Guadalajara, 2020. Agradezco a los asistentes y penalistas como también los comentarios de Ignacio Carbajal, Brook Lillehaugen y June Carolyn Erlick; todo error es sólo mío.

Related Articles

A Review of Yerba Mate: The Drink that Shaped a Nation

On any given day, millions of South Americans—in the subcontinent and around the world—would engage in the same ritual. We heat water (making sure it doesn’t boil), prepare the mate, and sip, sip and sip. But where does that green, earthy, addictive, and for many outside South America exotic, drink comes from?

Editor’s Letter – Indigenous Voices

Editor's LetterFrom the Maya in Guatemala to the Mapuche in Chile, Latin America’s Indigenous peoples are on the forefront of fighting for rights, whether against mining and deforestation or for land rights or the right to express themselves as a culture. We divided...

The Health of Indigenous Populations in Mexico: Disencounters

English + Español

In the year 2000, we participated with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in a medical-humanitarian project in impoverished indigenous communities in San Juan Cancuc, in the region of Los Altos de Chiapas.