Sentimental Soccer

River Plate and the Depth of My Sorrow

Between Wednesday, June 22, and Sunday, June 26, 2011, River Plate, the team I’ve been a fan of my entire life, was relegated to the second division of Argentina’s soccer league. The depth of my sadness during those days took me by surprise. Soccer has always been an important part of my life, and some of my first childhood memories are tied to River—my father taking me to the stadium, the lights, the greenest grass I had ever seen, the red and white waving flags, the whole place shaking when our team came out to the field. The news of River’s demotion—the winningest team in Argentina’s league history, and ninth in the historical rating of the International Federation of Soccer History & Statistics—startled fans throughout the world, and the incessant front-page news about everything around it proved that interest extended well beyond the strict realm of sports. Even though it occurred to me that it might be interesting to tease out the significance of the signifiers around River’s decline (the national resonance of management’s corrupt practices, the crisis of cultural institutions at the core of popular imaginaries, the end of soccer as a tale of heroism unthinkable in other social spheres), but during those days when River could not beat Belgrano de Córdoba, this intellectual agenda seemed like a grandiloquent, pompous and trivial exercise compared to the narcissistic intensity of my sorrow.

The fact was I was very sad. Too sad. Suspiciously sad for someone passionate about soccer, but nevertheless cerebral and rational (most of the time). An episode involving sports—no matter how traumatic—should not set off such deep sadness, I kept telling myself. But in this slightly demented interior dialogue, I could make no argument that could dissipate my sadness. And when I no longer wanted to—or no longer could—keep wallowing in the complacent mud of this excessive melancholy, I sat down and wrote a number of ideas, hypotheses, reasons to explain what I felt during those days’ declines, defeats, and demotions.

I’ve lived in the United States for more than ten years, and since the birth of my two sons (Valentín and Bruno, both of them huge fans of River like myself and my father), I have developed a decidedly schizophrenic relationship with the identity-forming rituals of progressive Argentinity and, most of all, with the practices and modalities of my own childhood in Buenos Aires, that my memory distorts over the double gaps of time and diasporic space. I pay close attention to what goes on in Argentina, I refer to current-day affairs of Argentine politics and cultural life with sharp cosmopolitan irony, but at the same time, I exhaust myself with vain attempts to reproduce for my sons a series of everyday routines and modalities (food, music, sports, movies, jokes and word games, overwhelmingly intimate physical closeness) that I imagine they would have if they were growing up in Buenos Aires.

To me, soccer is one of the most effective ways of bridging my family’s diasporic gap, but this is not specific to my relationship with my sons; the socio-affective significance of soccer is a proven global fact. Throughout the world, like very few other cultural phenomena, soccer is one of the names of the sentimental mediations that make up our (masculine for the most part) subjective identities, and the relations we form with our fathers, our sons, our friends. It’s not just soccer; there’s also politics, music, school, yes, but soccer is particularly effective as a way off invoking the sentimental universe of Buenos Aires that I would like to preserve here in the United States.

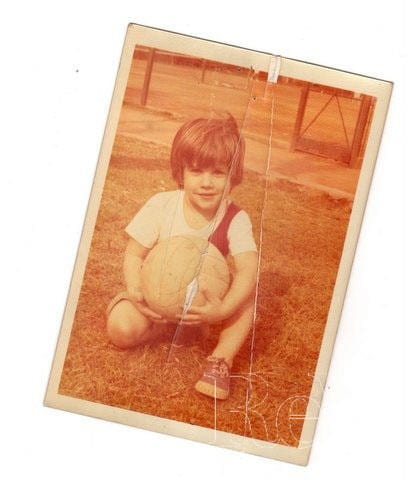

Soccer is not just soccer. Soccer is the emotional world that contains it and determines the weight of its social and subjective significance. So, for me, soccer is the name of vertical and horizontal forms of effect: in 1975 my father took me to the stadium for the first time to watch River win a championship after 18 years of defeat; and I was four when my dad took a picture of me in Hacoaj, with my first River jersey and soccer ball, posing as a professional player (I’ve taken similar pictures of my two boys in both Cambridge and Buenos Aires); beyond the hand of God and the most beautiful moves in the history of the game, my memory of Maradona’s goal against England in the 1986 World Cup is marked by the way my grandfather Juan and I celebrated and embraced for an eternity; the endurance and power of the liturgies of friendship depend, at least partially, on the convoluted shapes of love inscribed in the ways my Boca Juniors friends and I tease each other like kids. And as a mechanism of identification, River gave me an excuse to avoid participating in the disagreeable chauvinistic side of Argentines’ love of the national team (I’m a River fan, not of Argentina: I never cheered for a goal of a Boca player in la selección—Maradona doesn’t count, of course: he is universal patrimony).

That’s why the sadness I experienced in late June 2011 had very little to do with the demotion of River to the second division. Its strict sports meaning gets lost, indeed dissolved, in its overflowing socio-affective significance. If “River” is the way in which I work through my relationship to Buenos Aires and its cultural universe, then what was in play between Wednesday, June 22 and Sunday, June 26 was not the horror of having to play in the second division with teams like Defensa y Justicia, Patronato, Atlanta and Deportivo Merlo, but the literal degradation of one of the signifiers of that name my sentimental life. The exasperated and impatient response of those who don’t hear any emotional echoes in the deafening noises of soccer (my wife, for example) bothers me precisely because I am perfectly capable of seeing how ridiculous my over-investment in soccer is (so masculine, so Argentine, so idiotic). Thinking it through, perhaps it is this reproaching gaze (which is my own, most certainly) that leads me to intellectualize those days of River-Belgrano, and thus redeem my sorrow from its sports specificity and its apparent triviality.

The soccer fan in me tells me that I am unbearably pretentious in writing this essay. This inner voice tells me that the sadness of those days in June was (and is still) strictly sports-related because it was (and is) unimaginable that River has fallen so low, betraying its history, its colors, its stadium—and my own fresh memory of having felt, not so long ago, unbeatable, the best. But I have a twofold existence: the other part of me, the one that writes these lines midway between mourning and melancholy, shares space with the suffering sports fan. But if my sorrow can be explained through the evidence of affective relations and degraded childhood memories, the strictly sporting hypothesis carries some weight as well. Otherwise, I would stop caring about wins and losses, scores and rankings, rosters and injuries, for the year River will spend in the second division, and I would throw myself wholeheartedly to the process of mourning. But that’s not the case. I insist on the tortuous ceremony of watching River every Saturday over the Internet. Valentín and Bruno sit down and watch with me, they sing soccer songs they understand partially, we hug each other with every goal and at every step of the ritual that perhaps redeems the socio-affective charge that River’s demotion and my own diasporic status have degraded. And perhaps, through magical thinking, wishing Cavenaghi scores again, the three of us can will River into becoming champions once again.

Fútbol Sentimental

River Plate y el Tamaño de mi Tristeza

By Mariano Siskind

Entre el miércoles 22 y el domingo 26 de junio de 2011, Ríver Plate el equipo de fútbol del que soy hincha descendió a la segunda división del fútbol argentino. El tamaño de la tristeza que me invadió durante esos días (que se prolongó durante varias semanas) me tomó por sorpresa. El fútbol siempre fue una parte importante de mi vida, y soy hincha de River desde que mi papá me llevó por primera vez a la cancha cuando tenía 3 años. La noticia del descenso de Ríver—el equipo con más títulos en la historia del fútbol argentino—sorprendió a hinchas de fútbol en todo el mundo, y su presencia en la tapa de los diarios durante más de una semana puso en evidencia que el episodio condensaba significados que transcendían su dimensión estrictamente deportiva. Pero durante esos días en los que Ríver no podía ganarle a Belgrano de Córdoba, tratar de desentrañar los significantes de estos significados (corrupción dirigencial con resonancias nacionales, crisis de instituciones culturales fundantes de ciertos imaginarios populares, el fin del fútbol como relato de una heroicidad impensable en otros espacios sociales), me parecía un ejercicio grandilocuente y trivial frente a la intensidad narcisista de mi tristeza.

El hecho es que estaba muy triste. Demasiado triste. Sospechosamente triste para alguien apasionado por el fútbol, pero de todas maneras, razonablemente cerebral. Un episodio deportivo—me decía—, no importa cuán traumático, no merece ser envestido con tamaña tristeza. Pero nada que argumentase en este diálogo demencial disipaba mi tristeza. Y cuando ya no quise, o no pude, seguir revolcándome en el barro autocomplaciente de una melancolía a todas luces excesiva, me senté a escribir una serie hipótesis y razones mal enhebradas que explicaran lo que sentí durante esos días de derrotas y descensos. Voy a tratar de pasarlas en limpio.

Hace 10 años que vivo en Estados Unidos, y desde que nacieron mis hijos (Valentín y Bruno, los dos hinchas fanáticos de River como yo y como mi papá) tengo una relación marcadamente esquizofrénica con los ritos seculares de la argentinidad progresista, y sobre todo, con las prácticas y modalidades de una infancia porteña más o menos imaginaria que reconstruyo en función de la doble distancia del tiempo y la diáspora. Aludo a los asuntos de la política y la vida cultural argentina (que sigo en tiempo real por internet) con fina ironía cosmopolita, pero a la vez, me deshago en esfuerzos inútiles por reproducir para mis hijos un conjunto de estímulos parecidos a los que, imagino, tendrían si sus infancias transcurrieran en Buenos Aires.

El fútbol es una de las mediaciones sociales más eficaces de esta situación personal, un elemento privilegiado en este universo de prácticas que no me resigno a perder para mí y para mis hijos como efecto de la distancia diaspórica. Más acá y más allá del Río de la Plata, la significación socio-sentimental de este deporte es evidente: el fútbol es uno de los nombres del lazo afectivo que forma nuestras subjetividades (sobre todo) masculinas, y de las relaciones que establecemos con nuestros padres, con nuestros hijos, con nuestros amigos. El fútbol, la política, la música, el colegio, sí, pero el fútbol muy especialmente. El fútbol como relación social constitutiva de nuestro mundo social porteño y, para algunos de nosotros, post-porteño. El fútbol, en definitiva, como una de las maneras más eficaces de invocar a Buenos Aires, de nombrar su carga afectiva.

Así, entonces, el fútbol, no es sólo fútbol. El fútbol es el mundo afectivo que lo contiene y que determina el peso de su significación: mi papá me llevó a la cancha por primera vez cuando Ríver salió campeón en 1975 después de 18 años sin triunfos; me sacó mi primera foto con la camiseta y la pelota de nuestro equipo, posando como un jugador profesional, cuando tenía 4 años, y yo hice lo mismo con mis dos hijos en Cambridge y en Buenos Aires. Más allá de la mano de dios y de la jugada más hermosa de la historia, mi recuerdo de los goles de Maradona a Inglaterra en México ’86 está marcado por el abrazo infinito de mi abuelo Juan. La perpetuación en el tiempo de la liturgia de la amistad depende, al menos parcialmente, de esa forma enrevesada del amor que es la cargada con mis amigos de Boca Juniors, el clásico rival de Ríver. Y como dispositivo de identificación, Ríver me permitió una coartada porteña y barrial para no tener que participar del desagradable costado chovinista de la pasión argentina por la selección nacional (soy hincha de River, no de Argentina: nunca grité un gol de un jugador de Boca en la selección nacional—es mentira que Maradona sea de Boca; para mí, Maradona es patrimonio universal).

Por eso, la tristeza que sentí a finales de junio de 2011, tenía muy poco que ver con la eventualidad del descenso de Ríver a la segunda división. Su dimensión estrictamente deportiva se disuelve en sus determinaciones socio-afectivas. Si “Ríver” es el modo en el que elaboro un segmento (importante) de mi mundo porteño, entonces lo que se jugaba entre el miércoles 22 al domingo 26 de junio no era el horror a jugar un campeonato con Defensa y Justicia, Patronato y Deportivo Merlo, sino la literal degradación del significante que nombra ese conjunto de relaciones afectivas. La mirada exasperada e impaciente de quienes no depositan cargas afectivas de este orden en el fútbol (la mirada de mi esposa, por ejemplo) me molesta, justamente, porque yo mismo soy capaz de ridiculizar mi sobreinversión afectiva en el fútbol (tan masculina, tan argentina, tan idiota). Pensándolo bien, tal vez sea esa mirada reprobatoria (que es mía, claro) la que me lleva a sobreintelectualizar esos días de Ríver-Belgrano, y así redimir a mi tristeza de su especificidad deportiva y su aparente trivialidad.

El hincha de fútbol en mí -el que supo ir hace muchos años a la tribuna popular del Monumental- me dice que soy insoportablemente pretencioso por escribir estas líneas. Me dice que la tristeza de esos días de junio era (sigue siendo) estrictamente deportiva porque era (y sigue siendo) inimaginable que, Ríver haya estado estos últimos años tan por debajo de su historia, de su cancha, de su camiseta—tan por debajo de mi recuerdo fresco de habernos sentido los mejores hasta hace relativamente poco. Pero yo soy los dos: el hincha sufrido y el que escribe estas líneas a mitad de camino entre el duelo y la melancolía. Y entonces, si mi tristeza puede explicarse por la evidencia de relaciones afectivas y recuerdos de infancia degradados, la hipótesis estrictamente futbolística también estaría bien rumbeada. Porque si no, me desentendería del resultado de los partidos de Ríver por un año, mientras esté en la B, y me entregaría a corazón abierto al trabajo del duelo afectivo. Y sin embargo insisto en la ceremonia tortuosa de mirar a Ríver todos los sábados, ahora por internet. Valentín y Bruno me acompañan en los cantos de cancha, en el abrazo de gol y en cada uno de los pasos de una liturgia que quizás redima la carga socio-afectiva que el descenso de Ríver y mi diáspora degradaron. Y quizás, pensamiento mágico mediante, entre los tres podamos hacer que Ríver vuelva a salir campeón.

Spring 2012, Volume XI, Number 3

Mariano Siskind is an Assistant Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures at Harvard University.

Mariano Siskind es profesor asistente de lenguas y literatura románicas en la Universidad de Harvard.

Related Articles

Sports Diplomacy: A Dominican Adventure

I tried not to have my personal interests in sports and languages collide, but some things just can’t be avoided…

Sports: Editor’s Letter

I hate sports. As a little girl, I was always stuck on the softball outfield—the practical way of including a chubby, clumsy kid in the mandatory physical education class. I’d rather have been inside reading my favorite poet Edna St. Vincent Millay…

Sports and Political Imagination in Colombia

English + Español

A special exhibit entitled “A Country Made of Soccer” at Colombia’s National Museum features press photos, radio narratives, uniforms and other objects associated with the sport. Inaugurated…