Stigma, Discrimination and Human Rights

Health and HIV/AIDS

Six babies are born into the world each day with the HIV virus, many of them in Latin America. Last year, 1.5 million people with HIV were living in Latin America and another 440 thousand in the Caribbean, according to UNAIDS.

Advocates have long proclaimed that the vicious cycle linking HIV and poverty—poverty breeds HIV; HIV makes poverty worse—is rooted in the lack of fulfillment of human rights. This cycle raises unprecedented challenges to human rights, to health, to development, and to the very fabric of our societies. A pragmatic reality undergirds this advocacy for human rights: the promotion and protection of human rights is necessary not only because governments must adhere to their legal obligations to fulfill civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights; a human rights approach is also essential to effectively respond to the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Advocates thus need to remain concerned with why HIV/AIDS infection remains on the rise and why the global distribution of disease is so unequal both across and within countries. That is, we must ask ourselves why HIV now affects, almost exclusively, the most marginalized and discriminated against populations.

The first time that discrimination or human rights were explicitly named in any public health strategy was in the late 1980s, when Jonathan Mann directed the Global Program on AIDS at the World Health Organization (WHO). The first WHO global response to HIV/AIDS called for protecting the human rights of people living with HIV and AIDS, as well as for an attitude of compassion and solidarity. This went beyond a justified sense of moral outrage: it was found necessary also for public health and economic development. Discrimination against people with HIV was driving people underground, sowing fertile ground for people to be unaware of their status, to avoid testing and to further the spread of the virus.

Framing this global strategy in human rights terms allowed it to become anchored in international law, and therefore made governments and intergovernmental organizations publicly accountable for their actions toward people with HIV/AIDS. Governments became responsible from a human rights and health perspective to make every effort to put policies and programs into place to reduce the impact of HIV and AIDS on people’s lives.

These efforts require attention to the fact that people are vulnerable to becoming HIV-infected and, once infected, to receiving adequate care and support. Their ability to obtain services and to make free and informed decisions about their lives is directly linked to human rights. Individual, programmatic and societal factors affect people’s likelihood of becoming infected, and once infected, of receiving adequate care, support and treatment. And it means recognizing that the extent to which all rights—civil, political, economic, social, and cultural—are respected, protected and fulfilled, is relevant both to who gets infected and to what is done about it.

Providing condoms or even anti-retrovirals are critical steps, but they are not enough. Strategies must consciously and explicitly set out to reduce the vulnerability of the marginalized. This includes identifying and modifying laws, policies, regulations or practices that discriminate against certain populations. Work over the last 15 years has shown us that HIV-related discrimination and stigma are a key policy issue. This is true for both HIV related stigma, the process of devaluing people with real or perceived HIV status, and HIV related discrimination, the institutionalized denial to access to a multitude of things ranging from jobs to health care.

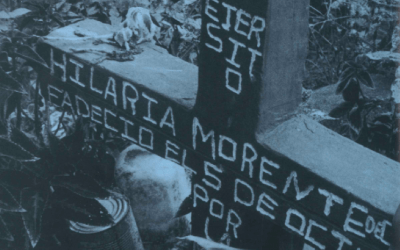

Examples of HIV-related stigma and discrimination abound. In some places, people living with HIV and with AIDS have difficulty obtaining access to food, housing, and education. In others, they are denied health insurance and employment, denied access to medical care or are kept from traveling internationally. Governments in many places continue mandatory HIV testing of people assumed to be at high risk of infection such as sex workers, intravenous drug users, gay men, ethnic minorities or members of other discriminated populations. Asylum-seekers, migrant workers, and students in any number of countries are also mandatorily tested, then denied entry if they are found to be HIV infected. In other places, educators and outreach workers are arrested, and violence against people living with AIDS or HIV continues without punishment. Gender based discrimination, including the lack of equal rights in marriage and divorce and the access to inheritance or to education, increases women’s vulnerability to becoming infected with HIV and affects the ability of women living with HIV to get treatment and care.

These forms of stigma and discrimination must be taken into account in developing HIV policies and programs. If HIV programs do not address stigma, discrimination and human rights, behaviors will not change and the epidemic will continue to disproportionately affect society’s most marginalized groups. Manifestations of stigma and discrimination and the processes used to address them are, thus, fundamentally human rights issues.

In all cases, human rights are concerned with improving health and well-being in the context of international human rights law. International human rights documents are relevant to the prevention, treatment and control of HIV and AIDS. Every country in the world is now party to at least one human rights treaty that includes attention to rights relevant to HIV/AIDS. Thus, every country is legally responsible and accountable under international law for human rights as they relate to HIV/AIDS.

These treaties focus on non-discrimination and on equality. They deal with civil and political rights, such as the right to information, and with economic, social and cultural rights, such as the right to health. Some of these treaties are more focused on specific populations (like the Convention on the Rights of the Child) and others focus more on specific issues (like the Convention Against Torture), but all fall within this basic framework.

The relevance of this is that the consensus that exists around human rights norms can make it possible to find common ground among very diverse partners—governments, NGOs and other civil society actors. The formal human rights system has an explicit focus on transparency and on the accountability of governments to their populations and to the international community. It requires that concrete benchmarks and targets be set against which progress can be measured. In relation to health—and therefore relevant to HIV/AIDS—this includes attention to both underlying determinants and the availability, acceptability, accessibility and quality of health systems, as well as attention to their outcomes among different population groups. This helps in establishing priorities, as well as strengthening accountability.

Governments are responsible not only for not directly violating rights, but also for ensuring the conditions that enable people to realize rights as fully as possible. Explicitly looking at governmental human rights obligations in relation to HIV/AIDS means recognizing that three elements of adherence to rights standards—to respect, to protect, and to fulfill—are essential, interdependent, and indivisible. Governments are legally responsible for complying with this range of obligations for every right in every human rights document they have ratified.

Governments have the obligation to:

Respect rights: States cannot violate rights directly in their laws, policies, programs, or practices.

Protect rights: States must prevent violations by others and provide affordable, accessible redress.

Fulfill rights: States have to take increasingly positive measures toward the realization of rights—this means everything from passing legislation to allocating resources.

In all countries—even those with the best of intent—lack of resources and other constraints can make it impossible for a government to fulfill all rights immediately and completely. While the optimal balance between HIV strategies will obviously vary by country and community, resources are an issue because prevention, care and treatment, and measures to diminish the impact of HIV/AIDS all require a level of financial expenditure that might not be immediately available. Putting rights into practice is generally understood to be a matter of “progressive realization,” that is, of making steady progress towards a goal. But this is not an excuse for doing little or nothing. Benchmarks and targets must be set and they must be monitored. There is a recognized difference here between government incapacity, which is understood, and government unwillingness, which is unacceptable.

The principle of “progressive realization” is of vital importance to resource-poor countries. However, it is also relevant to wealthier countries because their human rights obligations include not only respecting, protecting and fulfilling human rights within their own borders, but also through their engagement in international assistance and cooperation.

Governmental obligations in relation to HIV/AIDS focus not only on the right to the highest attainable standard of health, but on the whole range of rights included in international treaties. Realization of any right in isolation would obviously not be sufficient to significantly improve the impact of HIV/AIDS on a population. The responsibility for health lies not only with the health sector but also with all of the other sectors of government whose laws, policies and actions can impact health.

Lately some have asserted that human rights and public health provide very different approaches to responding to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The contention is that a human rights approach mandates that individual privacy rights be protected at all costs, even despite their negative effects on the public’s health. But privacy, like most rights, can be restricted if necessary to protect public health. To decide what is a legitimate restriction, a government has to address these five criteria:

- The restriction has to be provided for and carried out in accordance with the law: this allows for challenge and redress if an abuse does occur.

- The restriction has to be in pursuit of a legitimate objective of general interest, such as preventing further transmission of the HIV virus.

- It has to be strictly necessary to achieve the objective.

- No less intrusive and restrictive means is available to reach the same goal; and…

- It can not be unreasonable or otherwise discriminatory in the way that it is written as a law or policy, or in the way that it is applied.

The burden of proof falls on those who want to restrict rights. And it is in genuinely responding to these last three criteria that evidence is needed, in particular to show that there is no stigma or discrimination in how the restriction is being carried out.

The imposition of any strategy must be informed by evidence and debated openly so that public health decisions, whether or not rights are to be restricted, are made through transparent and accountable processes. This is necessary to protect against the imposition of unproven and potentially abusive and counterproductive strategies, even when such strategies are motivated by genuine despair—for example, in the face of rising rates of HIV infection in hard-hit populations. Introducing human rights into HIV work is about processes, not the imposition of any preordained result.

Consciously considering stigma, discrimination and human rights has provided frameworks and instruments for organizing thinking and action about HIV prevention, care and treatment, and impact mitigation and the ways that this thinking can be applied to policy and program decisions. Human rights do not provide a different approach to HIV/AIDS work than the field of public health does; rather, human rights are relevant to the processes of determining and shaping HIV/AIDS interventions—the policy or program a country or an institution might want to put into place. The engagement with human rights is necessary not only because it is mandated by international law, but because the respect, protection and fulfillment of human rights is critical to mitigating the health status of HIV/AIDS on individuals and populations.

Explicit attention to stigma, discrimination and human rights not only strengthens our collective understanding, it also, more importantly, strengthens our collective endeavor to improve health and well-being. Through these efforts, the cries of newborns—in Latin America, the Caribbean and beyond—will be the collective cry of future generations as they contribute to the healthy development of society.

Fall 2003, Volume III, Number 1

Sofia Gruskin is the Director of the Program on International Health and Human Rights at the François-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights, and Associate Professor on Health and Human Rights in the Department of Population and International Health at the Harvard School of Public Health. She is the editor of the International Journal Health and Human Rights, an associate editor for the American Journal of Public Health, and is co-editor of Health and Human Rights: A Reader (Routledge, 1999).

Related Articles

Human Rights: Editor’s Letter

During the day, I edit story after story on human rights for the Fall issue of ReVista. During the evening, I work on my biography of Irma Flaquer, a courageous Guatemalan journalist who was…

ONGs en América Latina y los derechos humanos

Las ONG ofrecen mil modos de recordar la dignidad humana a los gobiernos y las sociedades. Las dos experiencias que esbozo en esta nota reflejan algunas de las estrategias asumidas por…

Peru’s Human Rights Coordinating Committee

The human rights abuses that devastated Peru from the early 1980s to the mid 1990s are once again an issue of debate in that country with the release of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation’s…