Technologies of Gender

The Transformation of Masculinity

It was a Tuesday afternoon in early June 2005, and I was sitting with well-known cosmetic surgeon Dr. Julien Martinez (a pseudonym to protect participant confidentiality) in his spa-like clinic office, nestled amidst the luxury boutiques of an upscale shopping mall in Caracas, Venezuela. His colleague, Dr. Richard Galindo, suddenly interrupted our conversation. When Dr. Martinez explained to Dr. Galindo (also a pseudonym) that I was visiting from the United States to carry out an ethnographic study on women, beauty, and cosmetic surgery, Dr. Galindo turned to me and asserted, “You should talk to men, too.” Curious, I asked the physician to explain, and soon found myself conducting my first interview with a man who had cosmetic surgery.

As Dr. Galindo’s story unfolded, I learned about his experience as a patient undergoing blepharoplasty—an eye lift. He explained that an eye lift erased the signs of fatigue and age that had accumulated over time. Dr. Galindo perceived the eye lift as essential to maintaining a busy medical practice, because patients associated good looks with the positive qualities of a successful physician: persistence, capability, and tirelessness. “So you see,” Dr. Galindo concluded, “men are just as concerned about their appearance as women. We just don’t talk about it.”

In the span of thirty minutes, my research approach shifted fundamentally as I began to consider the cultural intersections between beauty and masculinity. I realized that I had developed several biases about who had cosmetic surgery and why. To some extent, my assumptions were based in the fact that cosmetic surgery is an overwhelmingly gendered practice. In Venezuela, for example, women requesting cosmetic surgery outnumber men by nearly twenty-two to one. Before my serendipitous encounter with Dr. Galindo, I had interpreted this predominance as clear evidence of the ways in which beauty work was defined as primarily women’s work.

But Dr. Galindo’s account reminded me how men could be susceptible to some of the most fundamental contradictions between the ways that real human bodies vary and change, and Western expectations regarding beauty. Classical Greek philosophers such as Pythagoras and Plato developed notions of beauty that emphasized mathematical proportions and harmony, but often in ways that took the male body as the starting point. Such ideas persisted in early modern Europe through the works of Enlightenment thinkers, including Kant and Rousseau, who associated beauty with moral goodness. Ordinary people found similar values in fairy tales, in which the good and virtuous are described as naturally and harmoniously beautiful—a sharp contrast to the evil and corrupt, who are haggard, old, angular and ugly. Many of these stories feature noble men (such as the Pig King, the Beast, the Frog Prince) whose virtue and beauty have been magically misaligned. These stories carry cultural messages about the value of physical appearance, and they also reveal expectations about aesthetics and masculine power.

Dr. Galindo’s narrative reflected similar themes linking aesthetics with virtue. He argued that as he aged, cosmetic surgery was necessary to alleviate the growing dissonance between his physical appearance and his personal character traits. The interview clearly demonstrated that the culture of beauty presented opportunities and constraints for Venezuelan men, but it also raised important questions regarding how men from different socioeconomic statuses might engage in and justify cosmetic surgery.

To answer these questions, I began an anthropological investigation of the cosmetic surgery industry in Caracas, Venezuela. From 2005 to 2007, I observed more than sixty hours of surgery and spoke with nearly four hundred men and women, including patients, cosmetic surgeons, models, dieticians, psychologists, cosmetologists, politicians and street vendors.

I also scoured medical registry data in private clinics and publics hospitals to learn more. In Caracas, the healthcare system can be described in terms of stark contrasts: from bright and modern private clinics to the older, run-down public hospitals. These two systems—private and public—mirror class divisions in Venezuelan society. In one private clinic, serving a predominantly middle- and upper-class clientele, most men sought surgery to fix their noses, but liposuction and face and eye lifts were also popular. In the public hospital, where the poor and working class seek medical care, nose jobs were by far the most common procedure, followed by ear tucks. Still, the percentage of men undergoing cosmetic surgery in both settings was low. Just over eight percent of the patient population in the private clinic were men; in the public hospital, less than four percent sought cosmetic surgery.

As I pored over my notes and survey data, it was clear that men’s perceptions of cosmetic surgery—and their justifications for embarking on personal quests for transformation—varied widely, in ways that could not be attributed simply to issues of individual psychology, such as self-esteem, body image or vanity. Although my first encounter was with a physician who looked for positive character traits when he gazed in the mirror, I found the clinical encounter—when cosmetic surgeons directed that gaze toward men who were often of other social statuses—to be a rich site for exploring competing representations of masculinity. Consider the following ethnographic example.

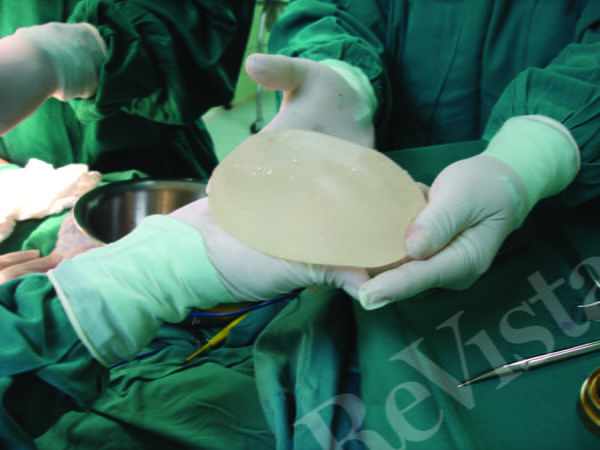

At 8:30 in the morning on May 7, 2007, I was sitting in the waiting room of the plastic surgery department in one of the largest public hospitals in Caracas. A notice was posted next to the sign-in desk, alerting patients that consultations for breast augmentation surgery had been suspended. A 1999 decree by President Hugo Chávez had prohibited public institutions from collecting service fees, which meant that all medical care in public hospitals, including cosmetic surgery, was available at no charge to patients. In a society enchanted with telenovelas and images of pageant princesses, hospitals soon became inundated with demands for breast implants. Unable to meet the demand, plastic surgery departments across the country were forced to limit the number of breast augmentation surgeries they would perform. Nevertheless, demand for cosmetic surgery remained steady, and the wait list for some surgical procedures was more than two years.

That morning, a young man dressed in a striped rugby shirt and jeans checked in with the administrative assistant. After a ten-minute wait, the nurse summoned him for his consultation with the all-male team of surgeons. He sat on the examination table, his nutmeg skin a warm contrast to the paler skin tones of the medical team. Carlos, who had just turned 18, wanted to straighten the bridge of his nose. When questioned why, Carlos told the doctors he had fractured his nose in a fight a few days earlier. After examining him, the doctors concluded that there was no evidence of a recent fracture, although it appeared that the nose had suffered trauma years prior. Carlos was dismissed to wait outside the examination room, while the team of physicians determined a course of action.

As Carlos waited, I sat with him to learn more about why he wanted to fix his nose, and he offered me explanations that diverged significantly from the story he had given to the surgeons. He thought his nose was “ugly” and “crooked,” and his friends teased him about it. Although he saw their mockery as friendly, Carlos could not help but internalize the message about his physical appearance, which he insisted was a normal way for a Venezuelan man to feel. “In reality, men take care of themselves just as much as women. But it has not always been this way.” I asked him what had changed. He explained that “it is because machismo is diminishing.” Machismo defines masculine behavior as dominant, but Carlos expressed confidentially to me—a foreign anthropologist and a woman—the conviction that it should not prevent a young man like him from engaging in beauty work. Even as he asserted his freedom from old gender constraints, Carlos also raised a third reason for seeking surgery: he now had asthma and found it difficult to breathe. A nose job, he asserted, could help him breathe better.

A few moments later, the surgeons called Carlos’s name, and I followed him back into the examination room. The surgeons decided to straighten his nose, and they told him that it could be done under local anesthetic. Doing so, they explained, would help them to fix his nose more quickly. Carlos agreed. He was told to lie on the examination table, and a resident began to inject a local anesthetic in his nose. When it was time to inject the interior of his nose, Carlos started squirming. “No, no, I don’t want to do this! It hurts too much,” he cried. The resident told Carlos to “just deal with it, stop moving, and act like a man.” As the anesthetic began to take effect, Carlos started flailing his arms. “I cannot breathe. I am telling you I cannot breathe!” The resident told him to calm down, reassuring him that he could breathe and that it was only the numbness that made it seem like he could not. The resident looked at me and said, “Can you believe the way he is acting? I have girl patients who never flinch when I give them a shot.” Carlos shot me an embarrassed glance, and then shut his eyes tightly. A tear streamed out of the corner of his eye.

Later that day, I accompanied the resident during his rounds in the main hospital building. We paused in the men’s wing to check on a couple of patients. One fifty-year-old man, nicknamed “El Peluche,” had been shot in the back, which resulted in complete paralysis of his legs. El Peluche frequently developed bed sores, but one sore had become infected. A deep, open wound emerged in its place, and El Peluche was waiting to get a skin graft to close it. Unlike Carlos, however, El Peluche would have to wait. The machine used to sterilize the skin was broken, and the hospital did not have the financial resources to repair or replace it.

In the hospital, physicians frequently complained about their ability to provide care in a setting that was unable to maintain a stock of basic supplies, including sterile gloves, syringes, and bandages. Often, the cost of purchasing supplies was passed on to patients, who frequently occupied hospital beds for the sole purpose of waiting for surgery; or their family members, who were often charged with bringing the necessary surgical materials from a local pharmacy. Recurrent cancellations—because of periodic electrical outages, equipment malfunctions, and shortages in sterile water, surgical instruments and anesthesia—lengthened patients’ wait times for surgery and corresponding length of stay in the hospital.

The crumbling infrastructure in the public hospital meant that there was little the surgeons could do for El Peluche except to clean his wounds. The resident pulled out a bottle of vinegar, a cost-effective disinfecting agent, and poured it into El Peluche’s abscess. Afterward, the resident remarked to me that El Peluche’s wounds were his fault. “He’s a criminal, and he got shot for it. All the men here are criminals.” I silently wondered whether his judgement extended to Carlos, who was treated just hours prior.

Almost a decade after completing my study, my experience in the hospital that day remains fresh in my memory. What has become clear to me is that beauty matters because people are driven to make aesthetic judgements of others. Patients evaluate their doctors’ appearance to assess their medical skills, and doctors, in turn, appraise their patients’ appearance to determine their worthiness. Carlos, in his attempt to mitigate any negative judgement, performed what he thought were the appropriate gendered expectations of the surgical team. He emphasized that his nose was broken in a fight, hoping to signal his masculine dominance rather than an aesthetic dissatisfaction—too feminine, or difficulty breathing due to asthma—too weak. Yet, the very act of having surgery became a way to challenge Carlos’s masculinity: his squeamishness during surgery was demonstrative of an insufficiently manly performance.

Carlos was not the first patient that I had encountered in the hospital who elected to have a nose job (rhinoplasty) under local anesthetic. Without the need to be sedated under general anesthesia, numerous patients could bypass the long wait for surgery, as their procedure could be performed in the hospital annex on an outpatient basis. Few patients were prepared for the pain, discomfort and blood, however.

Rather than acknowledge the fear that such experiences could generate, however, the surgeons castigated Carlos for not acting like a man. Although government reforms removed significant barriers to accessing cosmetic surgery, Carlos still had to seek care in an institution that reinforced the lingering inequalities in Venezuelan societies. His quest to see a modern and attractive man in the mirror led instead to an ordeal in which other men used their social status to tell him that he still lacked the male virtues that they were likely to see in themselves.

Spring 2017, Volume XVI, Number 3

Lauren E. Gulbas is a medical anthropologist and assistant professor at the School of Social Work at The University of Texas, Austin. Her work focuses on the intersections of culture and mental health.

Related Articles

Beauty: Editor’s Letter

Is it a confession if someone confesses twice to the same thing? Yes, dear readers, here it comes. I hate chocolate. For years, Visiting Scholars, returning students, loving friends have been bringing me chocolate from Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru…

Globalizing Latin American Beauty

Beauty seems to matter a lot in Latin America. Whenever I arrive in the region I am struck by the disproportionate number of attractive and stylish women and men who seem to be just walking around. I am always even more taken aback by airport bookstalls crammed with…

Beauty Weighs in Argentina

Argentines believe that “success” comes from luck and not as much from hard work and efforts, according to a recent survey conducted by the University of Palermo. This may work…