The 10% Solution

Bracero Program Savings’ Account Controversy

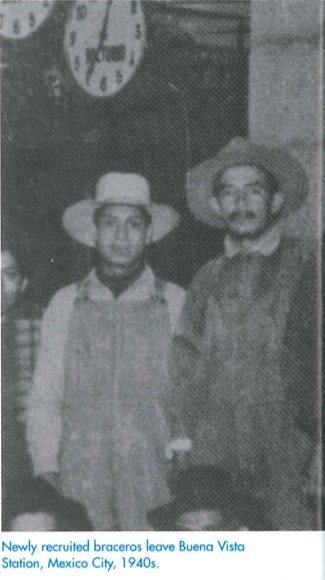

Distinctive among recent demonstrations on the streets of Mexico City have been protests organized by retired and often impoverished men employed temporarily and under contract in the United States more than thirty years ago. On April 7, 2003, more than 400 members of the organization Alianza Braceroproa and their families blocked the entrance to the Congress. These former braceros then proceeded to the President’s house to insist once again that the government compensate for its negligence during the bracero program (La Jornada, April 8, electronic version). With great hardship, ex-braceros travelled from all over Mexico to graphically present their complaints in the capital, reflecting their desperation, their determination and their belief that their cause is just. Moreover, their public presence serves a reminder of the often tragic human cost of migration to the United States.

Mexican and U.S. organizations representing these workers have repeatedly attempted to force the Mexican government to answer for its role in the bracero program, a guest worker program that dispatched Mexican immigrant workers all over the United States from the early 1940s to 1964. Denied other venues, these ex-braceros have brought their pleas for justice before the public in both countries through demonstrations and public discussions. Indeed, a major class action lawsuit filed in U.S. district court in 2001 focused public attention on their plight and identified many relevant problems. The place of braceros in the long, complicated and sometimes tragic history of Mexican immigration to the United States is unique but their plight reflects many of the contradictions, problems and suffering faced by all Mexican immigrants.

The braceros were employed as temporary contract unskilled workers in agriculture in the United States from 1942 to 1964 and for a short time during the war time on the railroads. Originally conceived and negotiated during World War II by the Mexican and U.S. governments as a short-lived but significant component of Mexico´s collaboration in the war effort, the bracero program was devised to solve rampant labor shortages in the United States. The Mexican government did not enthusiastically receive the first 1941 petitions of the U.S. government to permit the emigration of temporary workers for agriculture, mines and railroads; the memories of the painful repatriations of the 1930s were agonizingly close in time. However, the Mexican government eventually acceded. The formal binational nature of the U.S. government proposal and the full incorporation of the Mexican government into the migration proposal seemed to bode well for the program. Indeed, negotiators from both governments sought to include mechanisms that would protect the workers, guarantee minimum working and living conditions, and assure that they would return home safely at the conclusion of their contracts.

The first small group of workers to be recruited, contracted and transported to the United States headed toward Stockton, California in the summer of 1942 to harvest the sugar beet crop. However, the agricultural program spread quickly. Agricultural employers from all over the country wanted to avail themselves of the seemingly endless supply of workers from Mexico; the quota of agricultural braceros allowed to work in the United States at any one time would reach 75,000 by 1945. Despite pleas from many U.S. industrial employers to broaden the bracero program, only the railroads were eventually included. The highly organized and unionized railroad industry presented a particularly challenging scenario, but agreement was reached and the railroad braceros were dispatched to the United States in May 1943 for the Southern Pacific Railroad. The quota for railroad braceros reached 50,000 in 1945. Although the railroad program was immediately dismantled at the conclusion of World War II, the agricultural program survived. With pressure from agribusiness, the program underwent several bureaucratic transformations until 1964, when finally public outcry finally convinced the U.S. government to close it down.

The position of the Mexican government as a full partner in the bracero program only lasted through World War II. The desperation of many employers in the United States and the moral imperative of the war effort left no alternative for the U.S. government other than to approach the Mexican government as a peer during the war. Binational cooperation in a specific migration program of this kind is something the U. S. government does not generally do. During the special war environment, however, the U.S. government had to take Mexican negotiators seriously when they detailed their specifications for the working and living conditions of the braceros. It is true that the Mexican government could not completely anticipate how the contract requirements would be implemented or if they would be effective, but the documents indicate the contracts were negotiated in good faith.

Although the original agreement included many guarantees such as fair wages and subsidized transportation for the braceros, we will focus on the now controversial savings’ account clause, the subject of a modern-day class action suit. Mexico proposed that agricultural and railroad employers be required to deduct and forward 10% of the braceros salaries to a bank designated by the U.S. government, to be later transmitted to Mexican banks where the workers could recover that portion of their pay. The Mexican government feared an avalanche of undocumented migration to the United States spurred by the announced availibility of jobs north of the Rio Bravo. They promoted the saving accounts in the hope that at bracero program participants would have an incentive to return to Mexico. Further, Mexican negotiators sought guarantees of a certain nest egg “colchón” for repatriated braceros so that savings from their accumulated earnings could pay a mortgage or open a small business.

Not surprisingly, the mechanics of administrating the savings´ accounts quickly became complicated. Regional government officials finally came up with administrative procedures for employers to comply with the required payroll deductions, which eventually were deposited in collective accounts in Wells Fargo Bank in San Francisco. The evidence tentatively indicates that railroad employers were conscientious about making and recording the savings’fund deductions and submitting them accordingly. We do know, though, that from 1942 to 1948 Wells Fargo headquarters’ in San Francisco received deposits from the bracero program to the tune of many millions of dollars, although probably short of the $50,000,000 that would represent 10% of the total salaries of agricultural and railroad braceros for period of time. The savings´fund clause was not renewed after 1948.

Wells Fargo has produced enough documentation to prove that the bank did forward those braceros’ deposits to México. Wells Fargo held accounts of the Mexican government in the United States during World War II, so presumably the institution already had reliable methods of assuring the safe arrival of funds in México. Savings accounts were sent to the Banco de México, then to the Banco Nacional de Crédito Agrícola for campesinos, and to the Banco de Ahorro for the railroad workers.

Theoretically, after having completed their contracts and returned to México, the braceros could easily retrieve their savings’ accounts. However, no guidelines had been developed for the actual return of the savings. Neither the contracts nor the original negotiators anticipated that the banks in question, sometimes conspiring with Mexican government officials and agencies, would fabricate elaborate obstacles that prevented the braceros from receiving their savings. For example, some braceros returned directly to their place of origin far from Mexico City with no direct access to the designated banks. Likewise, the banks requested documents that the braceros would never have had; bank tellers cooperated with individuals to extort savings that had not yet arrived in México and been posted to the accounts. Archives in both the United States and México are replete with complaints lodged by repatriated braceros that they were unable to retrieve that 10% of their earnings for a variety of reasons.

Some braceros did retrieve their savings. A history dissertation written in 1984 claims that the Mexican banks did indeed return the bulk of the moneys. However, since the banking institutions have not produced verified individual receipts, the exact number will probably never be known. Moreover, given that the documentation of the wartime railroad program was more extensive, it is likely that more railroad braceros than agricultural workers received their savings’ accounts. However, the blame lies with the planning and implementation of the bracero program; the banks were not required to account for their distribution of the savings’ accounts.

The issue of the savings’ accounts faded for many reasons. After 1948, savings´ funds deducations were no longer taken. The binational character of the bracero administration virtually collapsed after World War II. The termination of the war emergency returned the balance of power to the U.S. government, thus neutralizing the potentially effective advocacy role of the Mexican government. Moreover, many ex-braceros were not in Mexico to claim their money since an undetermined number either stayed in the United States or returned there to work. Still more ex-braceros unfortunately came to accept that they would never receive their savings, although significantly they did not forget. However, it appears that the deposits remained in the designated accounts in Méxican banks for some time.

As ex-braceros in both counties reached retirement age in the early 1980s, they collectively began to reminisce about their work histories. Old memories easily surfaced that part of their hard earned salaries remained in limbo. While many other aspects of the bracero program deserve equally harsh criticism, the savings’ accounts controversy has come to epitomize the injustices directly experien ed by the ex-braceros.

The braceros’ local reuniones eventually involved younger generations of relatives. A core of supporters emerged to actively organize retired workers and their families into associations that could articulate their anguish with this tragic side of the bracero program. Representing local bracero groups in both Mexico and the United States, California resident and bracero relative Ventura Gutierrez founded Braceroproa in 2000 as an umbrella organization gathering together local bracero groups and venting their frustrations with the eventual objective of seeking redress. While the organization’s claims to directly represent 30,000 ex-braceros may be exaggerated, no doubt exists that Braceroproa accurately expresses the anger and desperation that many ex-braceros feel at not being as recognized as productive workers during and after World War II. That many did not receive their savings’ accounts underscores their dilemma.

However, the public discussions that local bracero groups and Braceroproa have generated since the late 1990s have resulted in much public interest in many sectors in both countries. Immigrants’ rights groups, labor unions, agribusiness organizations and public officials continue to express consternation over the injustices wrought against the Mexican immigrants contracted through the bracero program. The Mexican Cámara de Diputados appointed a special comission spearheaded by the PRD to investigate the charges, and propose solutions. Newspapers such as the Los Angeles Times, Dallas Morning News, La Jornada and Excelsior have assigned reporters to investigate and inform. These and others have published editorials that assign the final blame for the unresolved problems arising from the bracero program squarely with the two governments.

Eventually, the momentum created by the ex-braceros buttressed by media coverage generated support for concrete legal action. Law firms in California and Illinois became interested in the issue, and working with Braceroproa and other ex-bracero groups, eventually filed class action suits in San Francisco federal court in February of 2001 against the Mexican and U.S. governments, two Mexican banks, and Wells Fargo Bank to recover the savings’ accounts. Estimates place at $50,000,000 the approximate amount deducted from their salaries during World War for the savings’ accounts. Today, after compounding interest, that amount could total $500,000,000.

Unfortunately, after several rounds of arguments and motions, Judge Charles Breyer dismissed the suit for several reasons in September of 2002. Federal law prohibits legal actions against a foreign government in U.S. courts. Moreover, the suits against the Mexican banks were dismissed because those particular banks do not operate in the United States and finally the suit against Wells Fargo was disqualified because the institution provided some evidence that the moneys had been duly transmitted to Mexico. Most importantly, the judge openly sympathized with the plight of the workers and accepted the contention of their lawyers that the ex-braceros in all probability did not receive the savings’ accounts due them. He even suggested that ex-braceros present individual suits against the U.S. government, which is certainly a challege for workers and lawyers alike.

The bracero story did not end in August 2002. Almost immediately the California legislature approved a measure that extended the time limit for workers to present suits in the state. Lawyers for the plaintiff submitted arguments to overturn the ruling, although again in June of 2003 Judge Breyer ruled that the decision stood. Lawyers involved in the class action suit today continue to work with workers to achieve justice, although under different conditions. The propect of presenting thousands of individual lawsuits against the U.S. government involves very different strategies.

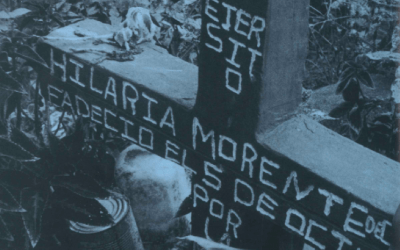

However, the persistence of the ex-braceros and their families means that the issue of the savings’ accounts will not disappear. As more information presumably becomes available, and other organizations become involved, the responsibility may well shift back to the Mexican and U.S. governments. In the end, the Mexican government assumed the role of advocate for the braceros and the U.S.government guaranteed compliance to the contract, which included full payment of wages. What is the legacy of the savings’ account controversy? First, the bracero program is finally receiving the attention it deserves. The public and active participation of ex-braceros has bestowed an undeniably human dimension to Mexican immigration of the 1940s and 1950s that escapes journalistic or academic analyses.

Likewise, the controversy embodies the contradictions inherent in any guest worker program. Contemporary proposals of guest worker programs that might govern the temporary migration of Mexican workers may strive to avoid the abuses so characteristic of the bracero program but they cannot complete sidestep problems inherent in contracting the labor of immigrant workers isolated from their social networks and support systems. Only the labor of guest workers is temporarily hired, not the whole person.

Herein lies the violations of labor and human rights inevitably associated with guest worker arrangements and specifically with the bracero program. Ironically, the recent public demonstrations of ex-braceros together with the formal, highly documented binational nature of the program during World War II provide a unique window into exactly how guest worker programs systematically undermine the human rights of guest workers by denying them access to the array of social networks, political resources and economic compensation that we usually associate with employment. Indeed, the experience of the bracero program clearly demonstrate that human rights are necessarily excluded from guest worker programs.

Fall 2003, Volume III, Number 1

Barbara Driscoll de Alvarado is a Latin American historian working as a researcher at the Centro de Investigaciones sobre America del Norte, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, in Mexico City. She was a Visiting Scholar at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies. She is the author of The Tracks North: The Railroad Bracero Program of World War II (Austin: CMAS Books-University of Texas, 1999).

Related Articles

Human Rights: Editor’s Letter

During the day, I edit story after story on human rights for the Fall issue of ReVista. During the evening, I work on my biography of Irma Flaquer, a courageous Guatemalan journalist who was…

ONGs en América Latina y los derechos humanos

Las ONG ofrecen mil modos de recordar la dignidad humana a los gobiernos y las sociedades. Las dos experiencias que esbozo en esta nota reflejan algunas de las estrategias asumidas por…

Peru’s Human Rights Coordinating Committee

The human rights abuses that devastated Peru from the early 1980s to the mid 1990s are once again an issue of debate in that country with the release of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation’s…