The Emergence of Religious Pluralism

A New Approach By the Peruvian Government

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), signed in 1966 under the auspices of the United Nations, gives people the right to freedom of religion. Article 18 of the Convention outlines this right both by guaranteeing individuals’ “freedom of thought, conscience and religion” as well as the right to manifest their belief individually and in community. The Convention also outlines that freedom of religion shall be recognized irrespective of race, color, sex, language, religion or political opinion. According to this international agreement then, not only do citizens have the right to hold and manifest their religious or other belief, but can also expect the state to ensure this right without discrimination.

As a doctoral student combining interests in Religious Studies and Human Rights, the right to freedom of religion as expressed and protected under the ICCPR is an international standard and thus becomes one important starting point in a discussion of freedom of religion. This is also the case in Perú where I had the opportunity to travel to this summer in order to conduct research for my dissertation.

I had always had in mind the idea of working in the geographical area of Latin America. My interest in Perú was peaked while reading a comparative analysis of the growth in the 1980’s and beyond of non-Catholic religions throughout Latin America. I learned that Perú is one of the countries which had experienced the most dramatic growth of non-Catholic religions outside of the Caribbean. Given Perú’s strong historical and contemporary inter-connectedness with the Catholic Church, I wondered how this shift was being lived, and what the possible repercussions were on freedom of religion and the wider political framework.

During my four-week stay, I had the opportunity to interview 35 people of many diverse backgrounds and interests: from human rights activists to religious leaders, elected congressmen to writers and artists. Everyone was open to my many questions about religion; in fact most were happy that someone had finally come to study what they perceive as one of Perú’s richest resources.

I quickly learned that the questions on religious freedom I was asking were the very ones being hotly debated in various segments of Peruvian society; they touched on issues dealing with the imminent political decentralization, the results of the Truth Commission (the conclusion of which was both celebrated and protested at the end of August) as well as proposed constitutional changes. The rest of this article will discuss in some detail the possible constitutional changes in regard to religion.

According to the religious leaders I interviewed, there is ample freedom to hold and practice the belief of one’s choice. Based on in-depth interviews with members of minority religious communities, including but not limited to, Anglicans, Baptists, Jews and Mormons, I was quickly persuaded that religious belief and practice are free and restricted only in so far as other rights are abided by. In this sense, article 18 of the ICCPR (see above) as well as article 2 of Perú’s 1993 constitution are observed. Article 2 of the Peruvian constitution states that:

Toda persona tiene derecho: 3) A la libertad de conciencia y de religión, en forma individual o asociada. No hay persecución por razón de ideas or creencias. No hay delito de opinión. El ejercicio público de todas las confesiones es libre, siempre que no ofenda la moral ni altere el orden público.

However, what of the question of religious discrimination? Are all religions and religious people treated equally in Perú? A short historical/constitutional tangent describing the development of religious freedom might be useful at this juncture.

As Guillermo Garcia-Montufar writes in his article entitled Antecedents, Perspectives, and Projections of a Legal Project about religious Liberty in Peru, until November 11th 1915, worship was illegal for all non-Catholic religions. On this day, the Peruvian Congress promulgated Law 2193 which abolished total protection of the Catholic Church by the state and allowed for freedom of worship for non-Catholic religions (until this time all non-Catholic religions were worshipping discreetly, at times secretly). The constitution of 1920 built on this notion and included in its text the freedom of conscience and belief—an act which pre-dated the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights by 28 years.1

We can see that at the time of these constitutional developments in the early part of this Century, the categorization of religions into Catholic and non-Catholic meant a new freedom for non-Catholic religions; non-Catholics were able to worship in public and officially marry within their faith. However, this does not mean that non-Catholic religions received the same status or protection under the constitution.

The Constitucion Politica Del Perú of 1993 states in article 50 that:

Dentro de un régimen de independencia y autonomía, el Estado reconoce a la Iglesia Católica como elemento importante en la formación histórica, cultural y moral del Perú, y le presta su colaboración. El Estado respeta otras confesiones y puede establecer formas de colaboración con ellas.

In my interview with Protestant Congressman Alejos of Ayacucho there are two words that are particularly difficult for those wishing to render the constitution more neutral vis a vis religions: the word ‘presta’ in the first sentence and the words ‘puede establecer’ in the second. The problem, in a nutshell, is that the Catholic Church is given not only special status, but the state lends its attention to it. In contrast, the state may establish forms of collaboration with non-Catholic religions. In reference to the Catholic Church then, the verb is active whereas in the case of the other religions it is conditional.

It is not only the protestant community which feels discriminated against due to this language. When President Toledo suggested the possibility of a constitutional re-negotiation—an issue which has not been ultimately decided upon—various suggestions as to the amendment of article 50 were made, including one by the Inter-confessional Committee of Perú (Comité Interconfesional del Perú) which is an organization representing diverse non-Catholic, but generally long-standing, religions in Perú.

Not surprisingly, there are many radically diverse opinions on how article 50 of the Peruvian constitution should be re-worked. Their common thread is that they all posit an answer to the same question: what type of state do Peruvians envision for themselves in the future? One difference between the groups is the answer they give—an answer invariably enmeshed with their particular political, economic and historical aspirations. Thus, some groups are lobbying for the reference to the Catholic Church to be deleted altogether, while others believe that it would be sufficient to remove the last clause of the first sentence, “y le presta su colaboración.”

Now, someone reading this article might at this point feel inclined to ask: what impact, if any, do these constitutional debates have on the practical point of religious discrimination in Perú? The fact is that the different treatment of the Catholic Church and non-Catholic religions written into the 1993 constitution translates into concrete privileges for the Catholic Church.

The most obvious examples of differing standards include: exemptions from certain municipal property taxes, financial benefit for donors who give to Catholic charities and finally an import tax exemption. However, it is not as though non-Catholic religions do not benefit from any sort of exemptions. In fact, non-Catholic religions are exempt from Rent Tax, General Tax on Sales and Selective Consumption by the importation of Donated Goods, the Tax of Vehicular Patrimony among others.

There are two important issues here, one of legal interpretation and the other of institutional capacity. The first point is that there are some exemptions which have simply been interpreted to apply to the Catholic religion only. This is usually done by narrowly interpreting words such as ‘convents and monasteries’ as applying only to Catholic institutions. Thus, for example, non-Catholic religions pay property taxes on the homes which house their ministers—an expense the Catholics are spared. The same is true for educational buildings, for example, which means that the private religious schools suffer under significant municipal taxes on their property. The result is a much heavier financial burden for non-Catholic religions and, in some cases, this translates into less monies for social outreach or missionary work.

The second important issue is one of institutional capacity. For some of the exemptions mentioned above, any religion would have to apply to the Ministry of Justice which housed, plainly translated, a Division of Catholic Affairs, to deal with these matters. Thus, until July 2002, all religions seeking relief of specific exemptions had to apply to this Division for approval. In this sense, the second sentence of article 50 which states “El Estado respeta otras confesiones y puede establecer formas de colaboración con ellas” in fact was not being put into practice because the Division in charge of collaborating with non-Catholic religions was one historically and practically devoted to Catholic issues.

This point has been taken up by religious freedom activists, lawyers, Catholics, Protestants and the Minister of Justice along with the President. The result is that on the 26 of July, 2002 a new Division within the Ministry of Justice was created which deals with Inter-confessional Issues (Dirección de Asuntos Interconfesionales) and is a sister to the Division of Catholic Affairs. The creation of this division is crucial not only because it seeks to rectify a representative imbalance by government vis a vis the Catholic Church and other religions, but because it gives non-Catholic religions a medium through which they can gain access to the government.

In my interview with the newly hired Director of this division, his excitement about the prospective work his division could achieve was obvious. The division’s mandate—a stack of written requests by non-Catholics lay on his desk ready to be processed—was clear. However, his work was delayed by one question the government has yet to answer: which religions should be considered by this new division? Should all groups which consider themselves religious be granted these special exemptions? Should there be objective criteria established that all groups claiming to be religious have to demonstrate?

The fear that underlies this question is one of abuse. The minister is very concerned about the possibility of quasi or non-religious groups forming and pressing for exemptions simply for financial gain and without being ‘truly religious.’ But, what is ‘religion’ or a ‘religious organization’? How does a society define, for practical purposes, religion? As the Director of the Division of Catholic Affairs pointed out to me, it is neither the expertise nor function of the state to define religion. While I agree that it is a notoriously difficult task, the Peruvian state has been defining religion since its inception as a Republic: it has been defining it as the Catholic religion. It is now time to develop this notion to include broader ideas of belief and move towards a less discriminatory model.

Fall 2003, Volume III, Number 1

Melanie Adrian is a doctoral student at Harvard who received a DRCLAS research grant to investigate religious freedom in Peru.

Related Articles

Human Rights: Editor’s Letter

During the day, I edit story after story on human rights for the Fall issue of ReVista. During the evening, I work on my biography of Irma Flaquer, a courageous Guatemalan journalist who was…

ONGs en América Latina y los derechos humanos

Las ONG ofrecen mil modos de recordar la dignidad humana a los gobiernos y las sociedades. Las dos experiencias que esbozo en esta nota reflejan algunas de las estrategias asumidas por…

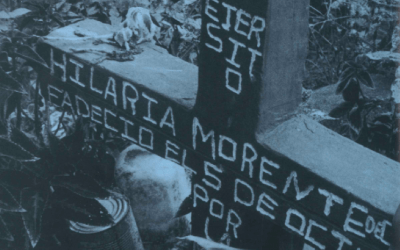

Peru’s Human Rights Coordinating Committee

The human rights abuses that devastated Peru from the early 1980s to the mid 1990s are once again an issue of debate in that country with the release of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation’s…