The Green Leap Forward

Chile’s Innovative Shift in Conservation

Tsunami shelter and overlook, designed and built by Samuel Bravo and Armando Montero in the Melimoyu reserve. PHOTO: ARMANDO MONTERO.

Chilean architect Cazú Zegers once stated, “The landscape is for Latin America what the cathedrals are for Europe.” The cultural power of territory has evaded every intention to dominate it for centuries. The Spanish conquerors unsuccessfully tried to impose the grid system mandated in the Law of the Indies, an operating system for territorial domination. And nowadays conventional urban planning has abdicated in the face of the spontaneous adaptation to the landscape of informal slums and architecture in all our cities.

With nearly 4,000 miles of coastline and expanding over more than 2,500 miles along the Andes mountain range, Chile features magnificent basins, fjords and glaciers, vast temperate evergreen rainforests, Patagonian grasslands and forests with some of the highest levels of biodiversity and endemism, as well as the driest desert on the planet and some of the most productive agricultural land in the continent. The Global 200 Initiative, promoted by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) together with the World Bank, has classified some of these ecosystems such as the Valdivian forest among the priority conservation sites worldwide.

In this context, the Chilean economy is strongly based on the extraction and exploitation of bulk copper, wood cellulose, salmon and fish powder, agricultural produce and most recently lithium. These highly intensive extractive activities produce environmental and social impacts at a regional, even planetary, scale that are challenging the country’s development model. The massive wildfires suffered during the Chilean summer of 2017 were in part fueled by massive monocultures of pines and eucalyptus, but also exacerbated by the deliberate action of radical groups reclaiming land taken from indigenous communities. On the other side of the country, in the arid zones of the Atacama Desert, large-scale mining operations are also challenging traditional villagers over the use of scarce water resources. These tensions have led to unprecedented political conflicts such as the resignation of two ministers from President Michelle Bachelet’s economic team in August 2017 because of the president’s decision to stop a 2.5 billion-dollar investment for a mining project near one of the main marine sanctuaries of Chile. In a territory stressed by the dynamics of massive extractive economies and the public’s awareness of its unique potential for conservation, Chileans begin to internalize the long-term commitments of such dilemmas.

In this context, the emergence of territorial and environmental conservation initiatives in Chile assumes great relevance. So far in the 21st century, the Chilean state has managed to establish national strategies for land conservation and biodiversity, with the ratification of the Convention on Biological Diversity and the approval of the Native Forest Act in 2008. Despite the lack of an appropriate legal framework, groups of philanthropists, individuals, corporations and foundations, as well as NGOs, have been leading initiatives parallel to governmental efforts to create a broad spectrum of private protected areas. This interest in the generation of natural, human and financial capital to generate a structure that allows the protection in perpetuity of private lands—particularly in areas of high environmental value—has been accompanied by remarkable innovations, both in legal and territorial planning areas.

The first efforts to promote private conservation came from wealthy philan-thropists such as Douglas Tompkins, founder of the clothing brands The North Face and Esprit, who invested nearly 300 million dollars in the purchase of more than 1.5 million acres of land in the Chilean Patagonia, or even wealthy locals like Chilean President Sebastián Piñera who bought 291,500 acres of native forest on the island of Chiloe in 2004 to create the Tantauco Park. In addition to these philanthropists, several foundations, corporations and individuals began to look for alternative ways to protect private areas in Chile. One of the main challenges was the lack of legally binding instruments such as land trusts to zone private land as conservation areas for perpetuity, as well as the lack of tax incentives to promote private investment in these issues.

In this context, the work carried out by Patagonia Sur, led by Warren Adams (MBA ’95), is especially significant. After an early success in the world of digital startups, Adams envisioned one of the first for-profit conservation funds in the world. Founded in 2007, Patagonia Sur purchases and permanently protects scenically remarkable and ecologically valuable ecosystems in Chilean Patagonia.

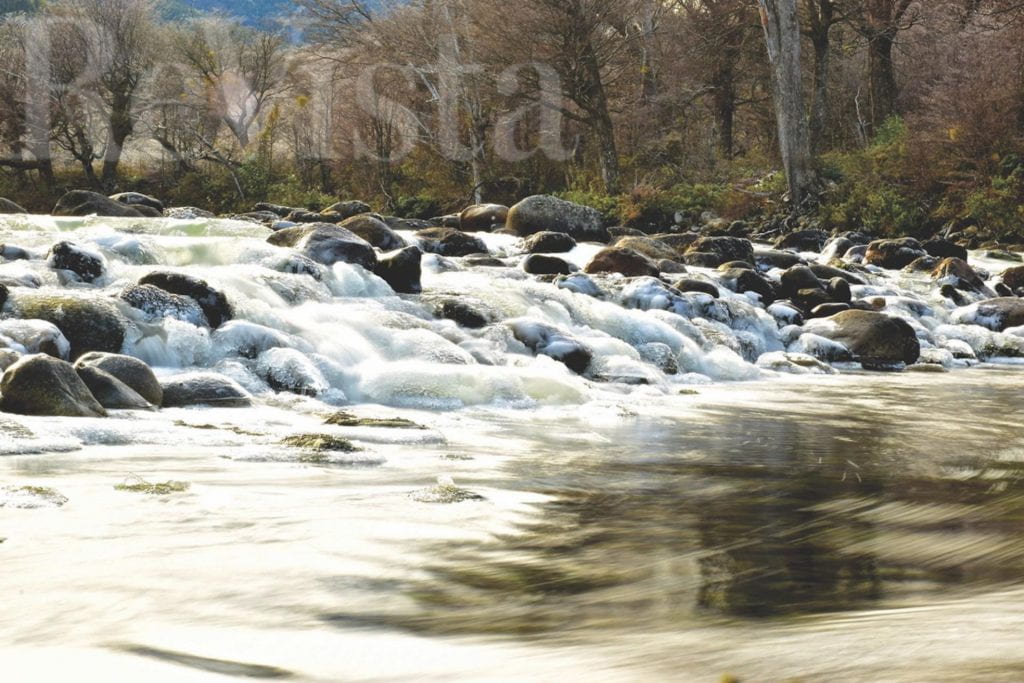

Views of Valle California reserve, the first for-profit conservation initiative developed by Patagonia Sur.

The Patagonia Sur model aspired to purchase 98,850 acres in territories of high environmental value—either a valley or a basin—for which, after a scrupulous environmental baseline study, a reforestation and conservation plan was developed in order to guarantee the recovery and care of its biodiversity over time. The business model originally created three income streams—an ecotourism venture that works on a vacation club or membership-fee model, a land brokerage and a carbon-offset business that sells credits to schools and corporations. The long-term value of conserving territories as virgin and remote as these would generate the expected returns for investors. The challenge was how to guarantee the resources to finance the conservation plans. This is when innovation converged with sound planning, architectural design, legislation and entrepreneurship. To consolidate his vision, Adams articulated a profitable conservation model. With the help of local consultants in conservation and landscape design, a territorial planning model was defined where at least 85 percent of the land stayed under protection and only a maximum of 15 percent was reserved for profitable low-impact uses, namely eco-tourism and real estate development under strict conditions such as design guides and a co-ownership regulation.

As an example of the Patagonia Sur model, the “Valle California” project in the remote province of Palena considered a protected area of 8,105 acres and seven Limited Development Areas (ADL), with only 25 lots of approximately 22 acres each. These lots were sold at prices ranging from $350,000 to three million dollars depending on their attributes. In this way, an investor bought land at a higher value than the market price in nearby properties, but his investment guaranteed perpetual maintenance, access and co-ownership of a natural reserve of more than 7,500 acres. The design of the ADLs, as well as the low impact infrastructure and constructions, had to deal with the climatic and logistical difficulties characteristic of such isolated areas. These difficulties led to the use of vernacular building techniques and an architectural language appropriate to the values embraced by southern Patagonia. Finally, to guarantee that more than 85 percent of the ecosystems could be protected for life, the legal office of Roberto Peralta interpreted and recycled an existing mechanism in the

Chilean legislation called “servidumbre voluntaria,” or voluntary right of use, under which it was possible to register and secure in perpetuity the conservation areas in each of the seven ecosystems recovered by Patagonia Sur, totaling more than 103 square miles of private land.

The Patagonia Sur experience allowed the creation of the first Land Trust in Chile: “Fundación Tierra Austral,” an independent non-profit organization that safeguards strict compliance with the conservation plans committed by the developers. Most consultants, architects and planners who participated in developing conservation plans for Patagonia Sur, have extended the model to other initiatives—in a sort of open source agreement—so other foundations, owners, cooperatives and corporations can participate in the protection of private lands, adding, up to date, more than 116,200 acres (181 square miles) of profitable conservation master plans in Chile.

Some critics like George Holmes, professor at the Sustainability Research Institute at the University of Leeds, call these initiatives “philanthrocapitalism” because they combine intentions as diverse as conservation and for-profit businesses; however, they recognize that—in the absence of resources or governmental mechanisms to promote non-profit conservation—new models such as Patagonia Sur could make conservation more effective in emerging countries like Chile. As Adams once mentioned in an interview for the Harvard Business School, “We learned that market-based solutions can be effective and efficient tools to augment the work of governments and NGOs on social issues.” In fact, Patagonia Sur nested several nonprofit spin-offs, like the Patagonia Sur Foundation, which helped nearby communities; the Melimoyu Ecosystem Research Institute (MERI), which studies blue whales and other endangered species; and Reforest Patagonia, a public-private campaign to plant a million indigenous trees in Torres del Paine and other national parks in Chile.

In June 2016, and after a decade since Adams established the profitable conservation model of Patagonia Sur, the Chilean Congress passed the first law establishing the “Derecho Real de Conservación” (Real Right of Conservation)—thanks to the work of the NGOs like “The Nature Conservancy,” “Así Conserva Chile” and several other organizations. This law grants every land owner the right to protect the environmental value, certain attributes or functions of a property in perpetuity.

Similar initiatives to Patagonia Sur have been replicated in the last decade in Chile adding more than 300 private protected areas in more than 3.9 million acres (6,093 square miles), equivalent to 2.2 percent of the total area of the country. Along with the enactment of the Real Right of Conservation Law—and after the tragic death of philanthropist Douglas Tompkins in a kayak accident—his widow Kristine McDivitt Tompkins and the foundation that bears his name fulfilled his posthumous desire to donate to the Chilean state about 988 thousand acres (1,543 square miles) of the park Pumalín (an area greater than the state of Rhode Island) in March 2017. Once perceived as a threat to Chilean geopolitical stability by the national government in the mid-90s, the perseverance and legitimacy of Tompkins’ commitment to the sustainable development of Chilean Patagonia found the necessary political ally in President Michelle Bachelet, who enthusiastically endorsed his will and opened the way for the recognition of his legacy.

The Tompkins’ donation along with the many private conservation projects and the Chilean National Parks Network make up a new protected area of 11 million acres (17,187 square miles), equivalent to the entire surface of Denmark, to which is added the recent expansion of the Marine Protected Areas of Juan Fernández, Cape Horn and Easter Island. With President Bachelet’s approval last February of these marine parks, Chile confirms its new role as a global leader in ocean conservation, protecting 103 million acres (160,937 square miles) of marine ecosystems, with a commitment to reach 395 million acres (617,187 square miles) of Marine Protected Areas in the coming years.

In summary, Chile has established more than 360 million acres (562,500 square miles) of sea and land conservation, which constitutes an increase from five percent to 38 percent of its protected land and sea in just four years. Chile leaves an irreversible legacy of conservation for the country and the world that capitalized the vision, commitment and consciousness of public and private initiatives in an emerging and still-developing country.

Spring/Summer 2018, Volume XVII, Number 3

Pablo Allard is the 2018 Robert F. Kennedy Visiting Professor of Latin American Studies at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. He is also Dean of the Faculty of Architecture and Arts at Universidad del Desarrollo in Chile and principal at Allard & Partners Landscape and Urban Design, where he collaborated in the creation of the Patagonia Sur conservation model.

Related Articles

Words that Matter

Those of us with little children often read The Lorax by Dr. Seuss to them at bedtime. The story points toward the past, because the Lorax is a ruin, with only residues remaining of something…

Prisoner of Pinochet: My Year in a Chilean Concentration Camp

English + Español

On September 11, 1973, at about eight o’clock in the morning, Sergio Bitar, one of Allende’s top economic advisers and the Minister of Mining, received a phone call from a colleague: the

One Long Night: A Global History of Concentration Camps

English + Español

In One Long Night: A Global History of Concentration Camps, Andrea Pitzer offers a thoughtful combination of investigative journalism and historical analysis that identifies the roots and