The Idea of Cuba

Whose Idea of Cuba? A Review by Kael Alford

Who could photograph a thought

as a horse is photographed at full gallop

or a bird in flight?

—José Martí (The epigraph from The Idea of Cuba)

First reactions to photographs are important. Photographs, in their slippery relationship to the observable world, often speak to us with quick impact, even before we can articulate to ourselves what they are saying.

For photographers, or those who look at a lot of photography, this impact is accelerated. The inscription to Alex Harris’s book holds special meaning for photographers, reminding us that the Cuban revolutionary José Martí lived his life close to an important moment in art history, the invention of still photography. It lets us know that we should read on. We photographers know quickly if we are drawn to the work or not.

The photographs in Alex Harris’ book have immediate appeal. They are also, for this photographer, immediately unsettling.

The text of the The Idea of Cuba delves into the history, politics and abstract notions of what it means to be Cuban, or at least what one American has learned about Cuban identity by observing Cuba. The cover image is selected from the most intimate series of images in the book—portraits of alluring, young Cuban women. The woman on the cover is posing next to a television set showing a man in a military uniform. For a book that contains as many complexities as this one, the cover image may initially raise doubts in the minds of those sensitive to cultural or gender stereotypes. But with this book, it’s important to keep looking—and reading.

Inside its pages, in addition to women, there are also cars. Rehabbed 1950s U.S. cars, photographed from the inside out so both the interior and the view through the windshield are visible in each frame. The interiors are lit so that the brightly painted trim, dashboard controls and car kitsch stand apart from the more muted tropical landscapes and dilapidated mansions framed through the cars’ windshields. It’s as if the viewer were a backseat driver. The driver is absent, or a ghost, as are the few figures in the streets who appear in the long exposures. The cars and the landscapes they frame, with their patina of age, are nostalgic and seductive in the way that old Ladas and flaking Stalinist blocks in eastern Europe are charming—unless of course you happen to live in one.

In contrast to the cars, the women are young, supple and scantily dressed, showing plenty of rich bronze skin. Sometimes they are faceless, their torsos examined in detail. In other images they look directly at us, daring us to be drawn in by their frank and confident sexuality.

In a third set of photographs are street scenes that all include a factory-produced bust or statue of José Martí, the Cuban revolutionary who spent his life as an exile in New York but devoted much of his work and writing to stirring up revolution among Cubans. His image is as ubiquitous as Lenin’s behind the Iron Curtain before 1989. Scenes that juxtapose the busts of Martí with gritty streets or playful children in decaying or neglected environments point to the contrast between the seminal ideals of that revolution and the modern realities of the Cuban state.

It’s well worth viewing the photos and imagining what those motivations might be before reading the text in the book. One’s shift in response to the images before and after reading the text may be striking.

At first glance, some of Harris’ visual metaphors are clear. Americans see Cuba through the economic and political relationships defined in the 1950s when the last American cars were imported and a trade embargo halted free trade, free travel and the free exchange of ideas between the two nations. As the photographs suggest, many Cubans see the world, literally, through the windshield of American cars. (Interestingly all the cars pictured are owned by men. The owners’ names and the location of the scene appear below each plate.) To an American viewing these images, Cuba looks like a country trapped in an economic and automotive time warp. Even the Cuban architecture reminds us of a particular, shared but colonial history. The view is nostalgic, gritty and it happens to be lovely.

Harris’s portraits of women are lovely too, but it’s not clear on initial viewing why these women are singled out. On first approach to the work, and before reading the text, it might seem that Cuba, which few Americans know at first hand thanks to the U.S. government’s travel ban, is populated largely by stunning, sexually astute nymphs. Only after we’ve read Harris’ essay do we lean that they are jineteras, “jockeys”— slang for women who trade sex for money, and other commodities. Why are prostitutes central to Harris’s idea of Cuba? We need to look beyond the photographs and read Harris’ essay to learn why.

There is a final group of images that provides a visual bridge between the previously mentioned groupings. The seductive portraits of women, American cars in the landscape, and busts of José Martí. gain context through a fourth set of pictures. This last set is the most visually direct and provides a fiber that tenuously holds the other disparate categories of photographs together. They are portraits of statues of women, statues on graves, in gardens, hotel lobbies, of women as angels, mothers and goddesses, echoing the ideals of the ancient Greeks or the sentiments of revolution as the fashion of the day required. They are iconic in their monumental roles. Some of the statues are broken; their worn expressions seem to reflect the loss of an arm or a wing, or the loss of a dream.

There is a resonance between these depictions of women and Harris’ portraits of jineteras, between the artful stone angels and the factory-produced busts, between the architecture of Havana in the car photos and the public art of the statues. Harris’ portraits of real women appear subtly defiant, beckoning, or composed, often gazing back at the camera as unapologetically as the camera gazes at them, while the women in the statues are frozen in iconic modes, in victory, in repose, in motherhood, in celebration. Is the author following a tradition or departing from it?

Both sets of women’s images remind us that the female form as muse and subject (or object) is nothing new, particularly among male artists. Photographs of beautiful young women in a book entitled The Idea of Cuba also imply that these women have been selected from the general population to represent Cuba in some way, not unlike the stone sculptures that came before them.

Certainly, Cuba, in one U.S. stereotype, is sexy. It’s warm, rhythmic ( at least Cuban music is), as well as politically defiant and transgressive. Even Cuban cigars are forbidden and coveted. In another U.S. conception, Cuba is a satellite, a tourist stomping ground, a historical colony and once an important stop on the slave trade route.

In the context of this book, Harris’s portraits of young women seem to allude to contemporary conceptions of Cuba, just as the artists whose work graces Havana’s famous Necropolis Cristóbal Colón found inspiration in their models when invoking the abstractions of spiritual life. Yet unlike sculpture, which removes the viewer from the model so we no longer recognize the individual or the time and place in which she lived, Harris’ portraits of jineteras portray more immediate flesh and blood and the particulars of each woman. Whether this is a tribute to or an over simplification of womanhood may come down to one’s perspective.

What we don’t learn is how these women might see themselves or what their lives might be like. Nor do we learn how their sacrifices, gains or circumstances are connected their own ideas of identity or country. The images themselves seem to be the product of transactions rather than relationships, but then, perhaps that in itself is telling about how our countries interact.

Too often, photographers’ writing muddles the clarity of their visual messages and one ends up wishing artists had stuck to what they know best. That is not the case with this book. Harris, who has collaborated extensively with Harvard Professor Robert Coles, has provided a text that is informative and revealing. An extended essay, interwoven with the images, is essential to understanding the author’s insights and intent. The text illuminates not only the history of Cuba but also the reflections of the photographer. Both are valuable.

We learn that the work was produced over a series of three trips. With each visit, Harris grew more familiar with the landscape of Cuba. First came the cars photos, then the Martí busts, and by the final trip, he had grown familiar enough with the country to travel and communicate on his own without the help of a driver or a translator. This is when he began taking portraits of the jineteras. In his writings, he describes his interactions with these women. He paid them, because it seemed to be the only way to get permission to take their photographs. He attempted to photograph them in public, with street life in the background, but found that he preferred photographing them in private, where their expressions were more revealing. Certainly there is a long tradition of voyeurism and photography behind these images, and Harris touches on some of his own discomforts with this tradition in his discussion.

Harris also outlines the efforts of the early Castro government to eradicate prostitution in exchange for equality and revolution, followed by prostitution’s resurgence when the twilight of Soviet-funded communism gave way to the economic apartheid of capitalism. Harris compares his personal values and attitudes toward women with the feminist leanings of José Martí and wonders frankly how much more enlightened he may or may not be.

In the end, it’s the portraits in the book that leave the most lasting impression, though we learn little about the women in these portraits as individuals. The complexity of these women’s lives, as Harris notes, is not captured within the frame. Harris is not a photographer immersed in Cuban life or subculture, so much as he is an earnest, sensitive and well-studied traveler affixing historical and symbolic lenses on a place that is foreign and yet has become familiar to him.

Viewing these photographs, an American who’s never been to Cuba may feel the push-pull effect of watching an interesting but reclusive neighbor through a fence. The subjects become familiar, even personal, but they ultimately mysterious, even taboo.

Fall 2009, Volume VIII, Number 3

Kael Alford is a 2009 Neiman Fellow. She is a photographer and documentary filmmaker.

Related Articles

Coconut Milk in Coca Cola Bottles

Common knowledge has it that virtually any movie, once removed from its original cultural context of production and reception, might be either misunderstood and misperceived or re-interpreted and re-signified. Likewise, we may agree that national cinemas seek to define, challenge….

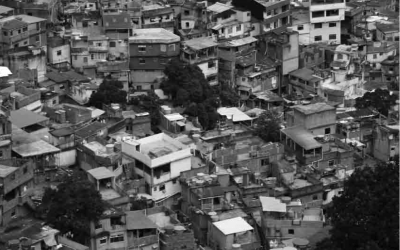

Neither the Sertão or the Favela

To frame the poetics of the ordinary in terms of subtlety and delicateness is to propose an antidote both for cynicism and for what I call Neo-Naturalism. Its appearance, at least in Brazilian cinema and literature, has been clearly identified, ranging from peripheral subjects…

Brazilian Cinema Now

Snow falling in the city of São Paulo, in southern Brazil? Taking a helicopter in São Paulo then arriving a few moments later in the deep wilderness of the Amazon jungle, half a continent further away to the north? Then meeting a white Asian tiger in the heart of the Amazon forest?…