The Japanese Brazilian Community

The large community of Japanese Brazilians is often seen as a model minority. Indeed, many Brazilians without any Japanese heritage are now taking pride in Japanese martial arts, food, culture and religions. Yet it wasn’t that long ago that Brazilians of Japanese origin were being seen as a “yellow peril.” And because of Brazil’s cyclical periods of economic instability, many Brazilian Japanese now find themselves as immigrants once more, now as second-class citizens in Japan. The history between the two nations is now 110 years old, and it is a complicated one.

At the end of the 19th century, there were too many people in Japan. There were too few in Brazil, especially with so much labor needed for its vast coffee plantations. Thus was born an exchange that would eventually make Brazil the country with the largest population of Japanese descendants outside Japan, more than one million and a half people.

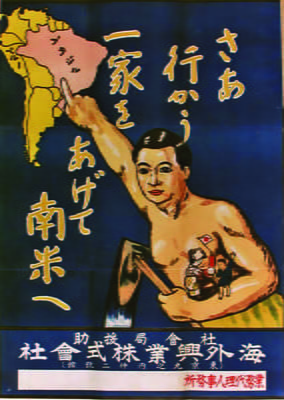

The first wave of Japanese migrants to Brazil arrived on June 18, 1908; a shipload of 781 people sailed into the port of Santos aboard the Kasato Maru. At first, most migrants intended to work hard for several years, with the dream of striking it rich and one day returning gloriously to Japan. However, few immigrants actually returned. In the pre-World War I period, the Japanese in Brazil became settlers organized independently or were promoted by the Japanese government, rather than contracted workers. The migration intensified in the 1920s and 1930s; in the mid-1930s there were more than half a million Japanese in Brazil.

Workers on coffee plantations later became independent farmers who settled together, forming Japanese enclaves known as colonies, scattered mainly around São Paulo and Paraná states. Social life revolved around Japanese customs, with little interaction with Brazilians. This increasing visibility of Japanese in Brazil propelled an anti-Japanese sentiment in the public and political sphere, rejecting this ethnic group as a “yellow element” not consistent with national identity.

World War II and the ensuing years proved to be a tough challenge for the community. Japanese—including the Japanese Brazilians—had a nationalistic devotion to Japan and its main symbol at this time, the Emperor. At the same time, Brazil itself had a nationalistic authoritarian regime under the dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas from the 1930s on. Caught between these two nationalisms, the Nikkei (descendants of Japanese) community suffered restrictions during World War II. In 1934, the Brazilian government established a compulsory assimilation program to foment nationalism; education was standardized throughout the country, and teaching in foreign languages was strictly forbidden in 1937. The Japanese were not allowed to run their schools, and their children were not allowed to study their language. In 1940, foreign language publications and newspapers were prohibited, and two years later Brazil broke off diplomatic relations with Japan. With Brazil and Japan on opposing sides in World War II, migrants took the brunt.

After the war, many Japanese Brazilians, unable to understand the news media in Portuguese, refused to believe that Japan had been defeated. Their education and worldview had centered on Japanese invincibility and superiority. These events provoked a traumatic confrontation in the community between the Nikkei who believed in the Japanese victory (Kachigumi) and those that accepted the Japanese defeat (Makegumi). Class division in the community was probably an essential factor in this split, one that even led to murder and terrorist actions from the Makegumi faction. The fanatical Kachigumi even assassinated some members of Makegumi who spoke against the ideal of invincibility of Japan.

But despite the divisions, the Japanese decided to remain, and Brazil became their adopted country, a possible homeland. Permanent residence in Brazil looked like a viable destiny among these migrants. Until the decade of the 1940s, nine out of every ten Japanese lived in rural communities. After many years of hard work, these migrants began to ascend socially. By the late 1950s, one out of every two Japanese lived in Brazil’s urban areas.

The second generation of Japanese born in Brazil (Nisei) became more involved in Brazilian national life. The Nisei saw themselves as individuals in the process of transition. In the 1960s, the Nikkeijin joined the middle classes and started to establish their economic, cultural and religious bases in the urban centers with high concentrations of Japanese migrants, such as Liberdade, a Japanese district in São Paulo. Engagement in industrial and commercial activities increased and families started to invest in the education of their children. In the first decade after the war, while a minority of Issei (first generation) and Nisei from the pre-war period remained attached to Japanese traditions and made efforts to preserve their ethnic identity, the majority underwent an identity crisis, which continued into the following decades.

The Japanese achieved considerable educational and socioeconomic success in Brazil—they had traveled a long and hard way from Japanese immigrant workers to Nikkeijin as a positive minority. The participation of Japanese officials and government in the promotion of Japanese culture and permanent settlement were decisive for the Nikkeijin in Brazil. The boundaries of ethnic identity between the Nikkeijin and the Brazilians were demarcated in a constructive way that was also promoted by the Japanese soft power, which helped the image of the Japanese Brazilians decisively as a model minority. Although the community continued to be divided in terms of generation, waves of migration, and prefectures of origin, the Nikkei could still be seen as an independent ethnic group.

Over the years, the Nikkeijin have become quite diverse and heterogenous. For example, in some communities in the countryside in which Nikkei from the third or fourth generation still use the term Gaijin to refer to people who have no Japanese ancestry, and many prefer to marry Nikkei. In contrast, many Nikkei are called Mestiços, because they are a mix of Brazilians and Nikkei (half or more than half Brazilian). Indeed, some cannot even be identified as Japanese descendants by appearance, but only by Japanese-sounding surnames. In contrast, the young generation of Nikkei cannot speak Japanese and have little attachment to Japan or Japanese culture. However, there is a new group of people without Japanese ancestry, who claim a certain level of “Japaneseness.” In general, these people are practitioners of Japanese martial arts, religions, enthusiastic fans of J-pop or any other Japanese-related activities. Many of these Japanese enthusiasts take their self-identification seriously by travelling and living in Japan for a period, learning the Japanese language and the philosophy behind these practices.

The Japanese contribution includes a diverse range of fields, such as agriculture; they are responsible for the increase in production of some vegetables and fruits brought from Japan and adapted to Brazil. Japanese introduced martial arts, such as judo and Aikido which became very popular among Brazilians. Japanese religions such as Buddhism and new religious groups also attract many Brazilians, not to mention the Brazilian fondness for Japanese food and arts.

Despite their success, the Nikkeijin also suffered from the country’s economic and political instability. In the 1990s, Brazil’s economic crises together with the need for blue-collar workers in Japan stimulated a substantial reverse migration. The Japanese government allowed the Nikkeijin— the first, second and third generation—to legally work in Japan, mainly in demanding industrial jobs. These reverse immigrants are called Dekasegi (roughly translated as “working away from home”), echoing the epithet of their ancestors, but in reverse. In Japan, the Nikkeijinhave built ethnic communities and are known as “Brazilians.” Many live without contact with the larger Japanese society, consuming Brazilian products and media. The construction of a Brazilian Nikkei identity as a minority group in Japan reveals the diversity within this transnational community. At the same time as they are considered a positive minority in Brazil, in Japan the Brazilians are seen in a lower position than the nationals. Most have no political rights and are seen as second-class citizens, performing unskilled jobs that no Japanese wants to do.

Nikkei identity becomes negotiated bilaterally with the respective majority societies. In Brazil, the Nikkei are native in culture and language, but they do not share the “racial” type usually identified as Brazilian, so they are identified as Japanese. In Japan, the Nikkeijin fit theoretically into the Japanese identity constructed on the tradition of valuing blood and race, but their lack of cultural and linguistic competence isolate them from interaction with the Japanese. In Brazil, family life and many Nikkei associations promote Buddhist rituals, typical Japanese festival and traditions. Therefore, the Japanese culture is not completely strange to many Nikkeijin. Conversely, in Japan, the Nikkeijin valorize Brazilian symbols such as samba, carnival and popular festivals, and in this way try to reinforce positive aspects of Brazil as a way of marking differences with the Japanese. Many Nikkeijin act as is contextually expected by the majority society in which they find themselves, justifying the label “Japanese” in Brazil and “Brazilian” in Japan—a dual diaspora.

The number of Brazilians in Japan was estimated at more than 300,000 during its peak. In 2008, however, during the Japanese economic recession, Brazilian workers faced layoffs, and after 2011, following Japan’s devastation by the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster, the number of Brazilians dropped to about 100,000. Now, Brazil is once again experiencing an economic crisis and 230,000 Brazilians are now estimated to be living in Japan. This movement could be called a circular migration; many of these migrants are caught in this circle between Japan and Brazil, depending on the fluctuation of the socioeconomic conditions of these two countries. The fluctuation of the waves of people coming and going is constant and also the maintenance of the recruitment system, communities and facilities for the Brazilians in Japan.

Although many of these Brazilians have little contact with Japanese except in the workplaces, many of their children are raised in Japan with Japanese classmates. However, these children performed poorly in school due to difficulties with the language and bullying in the Japanese school system, so they started to work when they were teenagers in the factories. In this sense, many of them are considered a lost generation, with no future in Japan nor in Brazil, perpetuating their position as citizens of the second class in Japan.

Despite these complications, the circular migration process brought much dynamism to both societies. Japan is in need of workers, and the presence of Brazilians exposes lots of old problems related to the minorities in the country and it is challenging the government and the civil society to find alternative ways to deal with them. At the same time, the Nikkei community in Brazil is renovating its ties and contacts with Japan. The people who lived in Japan and come back to Brazil bring with them a background and new ideas that have much impact in their community.

Fall 2018, Volume XVIII, Number 1

Rafael Shoji is a researcher at the Center for the Study of Oriental Religions (CERAL) at the Pontifical University of São Paulo. He has published on Japanese and Chinese religions in Brazil, Brazilian religions in Japan and Buddhism in Latin America.

Regina Yoshie Matsue is an anthropologist and professor at Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP). She did ethnographical research among Brazilians in Japan and in Brazil and has published widely on Japanese Brazilians religion, identity, health and gender.

Related Articles

From Vendedor to Fashion Designer

English + Español

Korean immigrants in Latin America are shaping and developing fashion economies there. Upon arrival, Korean immigrants to Argentina and Brazil may have been lonely, isolated and confused…

Shared Sentiments Inspire New Cultural Centers

English + Español

In the early afternoon of January 3, 2018, in the mountainous village of Shicang, Zhejiang Province, China, firecrackers burst into the air and flags waved in the wind as a parade of Clan…

Evidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st Century

A Review of Evidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st Century Contemporary Human Rights and Latin America On September 5, 1921, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, Hollywood’s then best-paid star, attended a party in San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel, drank...