The Journalist in an Open Pit Mine

The Adrenaline Keeps Flowing

The Veladero gold mine owned by Barrick in San Juan Province, Argentina, is a conventional open-pit operation. Photo courtesy of Gonzalo Quijandría

Some acquaintances asked me a few days ago if I missed journalism. Without hesitation, I answered yes: journalism had provided me with the tremendous privilege and opportunities for my work to be heard, seen or read, and this can turn into an addiction that is hard to break.

I left journalism 12 years ago when I decided to accept a job in the communications department of an international mining company, resigning from a position as editor of a business and economics magazine.

My first job had been at a television broadcasting station in Lima. Over a period of five years, I worked as a reporter, an interviewer and finally as anchorman for “Contrapunto,” a Sunday television show specializing in investigative reporting. Not only did the program achieve high national viewer ratings, it also became the standard for investigative journalism in Peru during Alberto Fujimori’s administration.

As a result of investigative reports broadcast on “Contrapunto” that included stories about alleged human rights violations and cases of corruption in the armed forces, as well as wiretapping, the Fujimori government in 1997 revoked the citizenship status of Israeli-born Baruch Ivcher, the owner of the television station I worked at. Ivcher had become a naturalized citizen of Peru several years earlier. This move by Fujimori’s government, designed by the president’s advisor, Vladimiro Montesinos, led to the company’s minority shareholders taking control of the television station. I resigned in protest.

The following year, in 1998, I was accepted into Harvard University’s Nieman Foundation program for journalists, which enabled me to pursue studies for one year and interact with some of the best journalists of my generation from 11 countries. At the end of my year as a Nieman Fellow, I returned to Peru accepting a job as editor of a business and economics magazine, a job I held for two years.

At this point in time, at the beginning of this century, then-Peruvian President Alejandro Toledo appointed my father, Alvaro Quijandría, as his Minister of Agriculture. At first, this appointment had no bearing on my job since the topics I had been working on were related to business and economics. But little by little I began to miss investigative reporting, particularly in the area of politics. I fully understood that my work might be the subject of criticism given my close family ties to the government, in the event I were to resume a career in political journalism. At that point, I went through a late vocational crisis. I thought that economic journalism would never succeed in filling the space left by political reporting. I began thinking about completely abandoning a career in journalism and reinventing myself in some related career. Within this context a job offer from the mining company appeared.

Compañîa Minera Antamina, a joint venture among Canadian, Australian and Japanese companies which became the largest mining project ever developed in Peru, offered me a job. Leaving journalism behind to accept a position at a mining company was not a decision made in haste. I’d been thinking about such an idea for a while—not the idea of working in the mining industry, about which I knew little despite my business editor job—but rather the decision of leaving journalism.

When I had been working as a journalist, I had reached the conclusion at one point that mining was not a good option for my country. The novels from the 1970s, which portrayed Peruvian miners as being heartlessly exploited, only reinforced that point of view. The novels were similar in tone to the description that film director James Cameron would make of miners of the future in his film Avatar. So when the offer came for a job in a mining company, I had conversation after conversation with friends who had some connection to the field and with others who were very critical of the role of mining in Peru.

I remembered how in one of the classes I took during my Nieman year at the Kennedy School of Government, a debate arose on a topic that seemed particularly surrealistic to me: “Is development good for humanity?” The arguments against that position centered on environmental impact as an undesired effect of progress. However, after that class, I couldn’t help thinking how far off that argument was for a country like Peru where, in the words of poet César Vallejo, “there is so much to be done.”

As I was mulling about whether to take the job at the mining company or not, I realized that no one uninvolved in the sector knew anything about it nor knew anyone connected with mining activity. These were the years of the “tigers of Southeast Asia.” High mineral prices had not yet arrived on the world scene, and there was little information in the media about mining.

What attracted my attention and in some way led me to accept the job was an assertion that would become reality only a few months later: “We need you to help get this mining project off the ground. Its construction will mean an extra growth point in the GNP this year.” How can you not want to be part of something so significant?

I began my job at Antamina the same day that the 38-foot diameter semi-autogenous grinding SAG mill entered into operation, a wonder of engineering installed at nearly 14,000 feet above sea level in the middle of the eastern Andean Mountains, 217 miles from Lima. In 2001, mineral prices had risen to appreciable levels, but talk of the Peruvian “mining boom” had not yet begun. One could still count on the fingers of one hand the number of transnational mining companies operating in Peru.

Antamina became the first mining company in Peru to talk about social responsibility and to start operations only after obtaining a social license, a process that often took years to build trust levels with the communities affected. This process actually enabled the construction of the mine to be completed ahead of schedule and under budget.

Antamina’s strategy in Peru was innovative, and at the beginning it was viewed with skepticism by the local mining industry, which years later ended up accepting—not without an absence of setbacks in its own mining operations—that things had in fact changed in the relationship between mining companies and communities.

I worked with this company for nine years, attempting to build consensus in the communities by implementing both mass and direct communication strategies. I established a policy of transparency and an open-door policy for the local media, I organized direct town hall meetings with the local population, and I produced a series of educational materials aimed at explaining the mining process and the technologies used to minimize environmental impact. To this very day, the process used to launch Antamina’s mining operation is studied around the world as a business success case, and there is no doubt that communication strategies contributed to that success.

Following this experience, it didn’t take me long to realize that I hadn’t left behind the adrenaline found in the practice of journalism for a quieter and safer line of work, because the mining industry explodes with intensity. As the years passed, mineral prices reached historic levels; communities neighboring mine deposits saw their income rise as a result of the influx of mining canon royalties (in Peru, half of the income tax generated by mining activities must be transferred to the municipal governments located near the site of the mine deposit)—resources that the local authorities were not properly prepared to manage. Thus, frustration grew among the communities upon seeing that they possessed financial resources to help them climb out of poverty but that their officials did not have the capacity and skills to execute development projects. Furthermore, mistrust also grew in the public opinion concerning the ability of the mining companies to effectively control their environmental impacts, an issue magnified by the more than 600 environmental liability sites identified in Peru dating back to the previous century. As a consequence of this complex set of problems, social violence began to occur more frequently. Even today, no effective formula to achieve social peace has been found.

During these past twelve years I have worked with various types of mining companies: Australian polymetallic mines, Canadian gold mines and the mining division of a Peruvian business group that has diversified operations and holdings in Peru and Brazil. The history of mining in the world over the course of this period has also suffered fundamental changes: it has gone from being an industry with a perpetually low profile to one that occupies news headlines in the media, and it has become the nucleus of social conflicts, some of them very violent and with loss of human lives.

For the media, the image and reputation of the mining industry that make up the intangibles that I am required to manage as part of my daily job have historically been complicated. A miner is always a new actor that appears on the scene of those areas in which the company operates, since his job is to search for minerals and to extract them at the sites where they are found. This fact of life in the mining industry makes it inevitable that miners will always be the viewed as the “new guys on the block” in the communities and this dynamic engenders mistrust.

I had never experienced this type of suspicion during my years in journalism. What the field of journalism had, particularly in television, is a high level of public exposure, and when an investigation was well prepared and adequately supported by evidence, people expressed their gratitude with their trust.

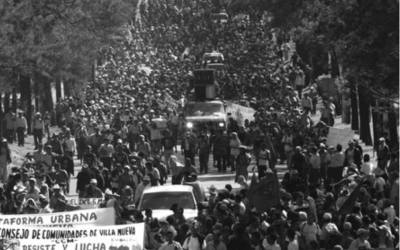

From the standpoint of the mining industry, building trust among the audience that I need to address is very complicated and it requires an extra dose of hard work and understanding. The main problem lies in the levels and degree of the violence in this relationship, as it is common to see highway roadblocks, public assemblies where “popular justice” is often administered (physical attacks not excluded) and hear constant criticism on the radio and in local newspapers.

That is the point of departure for mining projects, because it is becoming increasingly necessary to implement participative processes of open communication in business decisions that could have any community impact. Likewise, the environment of poverty in which most mining deposits in Peru are located (usually at the highest plateaus in the Andes Mountains), makes it essential for companies to develop social responsibility policies and projects.

Peru is preparing to receive the largest mining investment in its history: approximately US$50 billion in investment projects for the coming years. If these projects are successfully developed, there is no doubt that they will create an even deeper change in Peruvian society. An investment inflow of this magnitude will bring direct and indirect employment, tax revenues for the central and local governments, decentralized purchases of goods and services. However, if these revenues do not translate into the much-needed public infrastructure construction or increased welfare for the communities, outbreaks of social violence will increase.

I hope that the mining industry makes the most of the lessons learned over these past years and is able to address the challenge it faces. As a reporter, I experienced some of the events that may be considered part of Peru’s recent history. I covered the occupation of the residence of the Ambassador of Japan in Peru for four months by the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement, the wiretapping scandals by intelligence operatives in the government of Fujimori (whom I interviewed three times while he was president), the withdrawal of citizenship from Baruch Ivcher and Vladimiro Montesino’s dark sources of income. One might think that I could not experience moments as intense as those that I felt when reporting these incidents, but this is not so. These feelings come up at the popular assemblies, in the processes of public participation and in the direct negotiations with the community representatives where you sometimes feel like you are pushing a heavy automobile—but one with the power that is capable of creating opportunities for many people to climb out of poverty. This is the intensity that I discovered in the mining industry.

Winter 2014, Volume XIII, Number 2

Gonzalo Quijandría was a 1999 Nieman Fellow at Harvard University.

Related Articles

Making a Difference: Building Blocks

Since the first, unplanned visit of a Brazilian entrepreneur in 2011 to Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child, a diverse group of professors, practitioners, civil society leaders and other committed individuals at Harvard and in Brazil have…

Travails of a Miner, VIP-style

English + Español

Sergio Sepúlveda is a Chilean miner with an enviable salary—equivalent to that earned by a university-educated professional. He owns a brand new Korean-made car, and every three years…

Indigenous People and Resistance to Mining Projects

English + Español

Latin America’s governments and its indigenous peoples are clashing over the issue of mining. Governments, motivated by economic growth, have established legal frameworks to attract foreign investments to extract mining resources. When those resources are located in…