The Legacy of Che Guevara

His Significance in the Americas

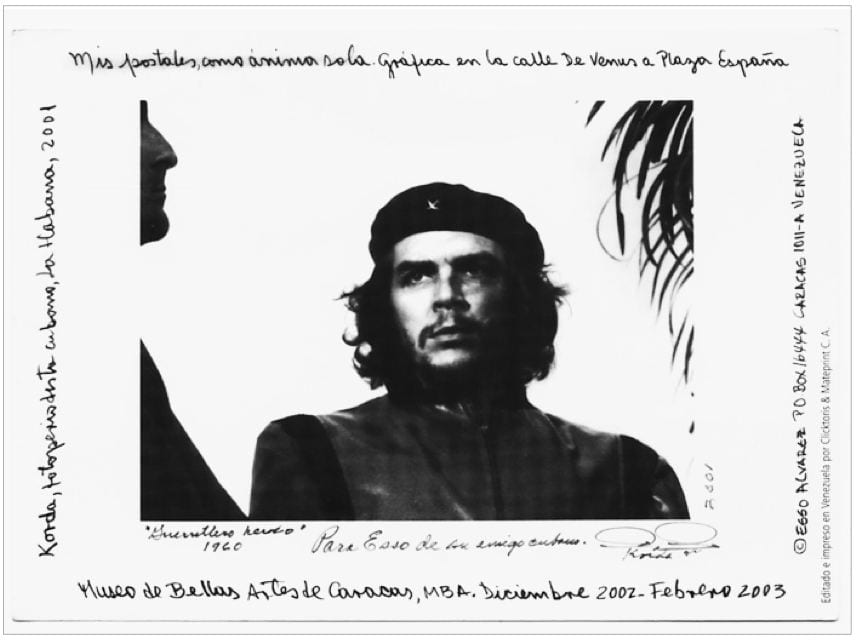

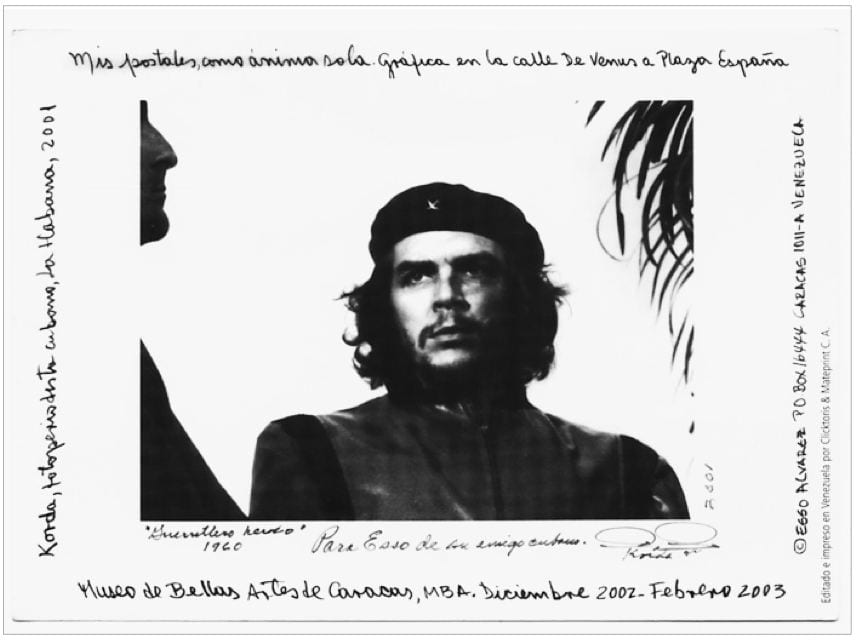

An art postcard displays photographer Alberto Korda’s iconic image of Che. Photo courtesy of Esso Alvarez

An October 2007 article in The Wall Street Journal intended to deprecate Ernesto “Che” Guevara on the 40th anniversary of his assassination in Bolivia. Instead, the article was an unintentionally eloquent description of his significance in the Americas.

The article, headlined “Forty years after, the shadow of Che still falls over Latin America,” reveals why the empire pursued Che with so much malice and assassinated him with so much hatred. Che was construed as the “ideologue of communism and the armed revolution against the West in the Third World,” too revolutionary even for Cuba, thus motivating Fidel Castro to send his great revolutionary collaborator abroad to promote the revolution in other countries.

“In his life, Che had scarce direct influence outside of Cuba, but his legend has done much more than sell t-shirts to discontented rich young people,” the WSJ article ironically noted.

“Che’s paranoid, anticapitalist economic doctrines have considerable appeal for Latin Americans. Many countries in the region have elected governments headed by Che sympathizers—from Salvador Allende’s Chile in 1970 to Evo Morales’ Bolivia and Rafael Correa’s Ecuador of today,” deplored the publication.

The article pointed out the supposedly negative effects for the region deriving from ideas inculcated during Che’s time. The article also expressed its concern for the wellbeing of the overall continent because of the example Che had set for Latin America.

“When Che was killed in 1967, the growth of productivity in Latin America was average compared to other countries, according to global estimates. But, from then on, it has fallen beneath the other regions. Only Brazil and Chile have had adequate developments, basically thanks to the extensive periods of rightist military governments, in which Cheismo was repressed.”

Then, the article conjectures: “Without Che’s legend, the annual growth rate would have been one percent higher. From there, it seems that the revolutionary has cost the region around 1.3 trillions of yearly internal development.” And the article emphatically concludes: “The shirts are cheap, but Che has been an expensive icon.”

While the article assumes that Che’s ideas led to the economic downfall of the region, in truth the economic and social disaster was the result of the neoliberal policies that Washington forced on the region. These were part of its global economic strategy in which it depended on military dictators and political repression to exercise imperial hegemony over the continent.

The representative democracy exercised by political parties was able to be controlled by the local oligarchies—in virtue of the neoliberal electoral rules—and was designed by Washington when it saw itself obligated to abandon the prior formula: stimulating social battles and armed revolutions such as that which triumphed in Cuba 50 years ago and which Che recommended with his example.

Now, U.S. transnational corporations, whose interests the WSJ reflects, observe with astonishment that, with the assassination of Che, Latin American people still have not stopped trying to obtain sovereignty and liberty for their nations.

Armed struggle was once the only path toward achieving revolutionary change and achieving sovereignity. The path has now been paved for electoral means to function as a resource for the promotion of popular aspirations from a position of power, and many revolutionaries on the continent have accepted the challenge as they lead their countries. A new scenario has been developing on the continent for the past two decades and for the first time in history, in which elected officials have come to power with the interests of their citizens at heart to an unprecedented degree.

These leaders are not always Marxists or revolutionaries—just like those non-Marxist patriots who chose armed struggle in the 60s—but they share a common and explicit belief in the importance of the defense of their nations’ independence and rejection of servile subordination to the hegemony of the United States that used to be the law of the land. That does not mean that now the empire and the oligarchies have become more understanding or that the struggle of Latin America’s people has become easier. Nothing is farther from the truth. The revolutionary fight continues to be very difficult because it must free itself from systems designed by oligarchs with game rules that give them advantages and supremacy of interests.

The new reality of Latin America, with the undefeated Cuban revolution and the electoral triumphs of several rulers with anti-oligarchic programs that affirm the sovereignty of their nations is, in very good measure, fruit of the rebellious Latin America of the iconic Che who confronted absolute dominion in the region that was the U.S, response to the Cuban revolution.

At the same time, the people of Latin America were not nor would ever be prepared to support tyrannies like that of Pinochet, genocides such as the Plan Condor and the submission of the dignity and sovereignty of their nations to the corporations through associations such as ALCA, in order to achieve the economic growth rates and Pyrrhic profits to which the WSJ alludes.

Che’s ideas were always those of an independent, united Latin America, with social justice, from the time the rebels banded together in Mexico to combat tyranny in Cuba. This ideology matured and deepened in the reality of the combat and in the confrontation with the bigger enemy, imperialism.

Che participated as a doctor in the expedition of the yacht “Granma” that disembarked in Cuba in December of 1956 with a contingent of 82 young, idealistic men. He took on an increasingly important role in the guerrilla army because of his tactical and strategic talent, as well as his courage in combat. Soon he was assigned to lead one of the five major columns in the Rebel Army and was the first to be promoted to Commander, a position that until then only Fidel Castro had obtained.

As a medical doctor with the guerillas, Che was a champion of careful attention to enemy prisoners, a practice that encouraged soldiers of the tyranny to surrender, convinced of the scrupulous respect for human rights of their insurrectional opponents. Che clearly identified with patriotic, Cuban ideology, and quickly turned into one of the principal leaders of the fight for liberation and the revolutionary construction in Cuba. After victory, he assumed the responsibilities of directing various areas of civil life without abandoning the area of defense.

He became president of the National Bank of Cuba and minister of industry and, in both positions, made important contributions to economic theory and practice in these fields—from the position of a revolutionary conducting a battle against the underdevelopment of a nation. His participation in international events and his contacts with Third-World figures extended his international prestige as one of the most representative figures of the Cuban revolution. Among his revolutionary qualities, most notable were his passion for justice, his humanism, his generosity, his constant practice of putting words into action, and the harmonic structuring of his political, economic and military ideas, all in the space of a short life. In the field of political ideas, he was a convinced Marxist who rejected intransigent dogmatism, stale doctrines and bureaucratic tendencies.

The exemplary way in which Che preached revolution has left a legacy much greater than the myth and image that today mobilizes millions of oppressed, exploited, excluded and dissatisfied people in the unjust world in which we live.

Che did not go to Bolivia to die, just as he did not come to Cuba to die, nor did he go to Africa to die before setting out to fight in Bolivia. He always wanted to demonstrate with his personal example the decisive action with which the people of the world had to act in order to shake off oppression. He understood the risk and readily accepted it.

An art postcard displays photographer Alberto Korda’s iconic image of Che. Photo courtesy of Esso Alvarez

El Che en los Ideales de Latinoamerica

Su Importancia

Por Manuel E. Yepe Menéndez

Sería difícil conceptuar la huella del Che Guevara en América con más elocuencia que como lo hizo—pretendiendo denigrarlo—un artículo del Wall Street Journal en octubre de 2007, al cumplirse 40 años de su captura y asesinato en Bolivia.

El artículo, titulado “Cuarenta años después, la sombra del Che aún pende sobre América Latina”, revela los motivos por los que el imperio persiguió con tanta saña y asesinó con tanto odio a quien identifica como “ideólogo del comunismo y de la revolución armada contra occidente en el Tercer Mundo” y sostiene que el Che era demasiado revolucionario hasta para Cuba, razón por la cual Fidel Castro envió a su gran colaborador revolucionario a promover la revolución en otras tierras.

“En vida, el Che tenia escasa influencia directa fuera de Cuba, pero su leyenda ha hecho mucho más que vender camisetas a descontentos jóvenes ricos”, ironiza el artículo del WSJ.

“Las paranoicas doctrinas económicas anticapitalistas del Che tienen considerable atractivo para los latinoamericanos. Muchos países en la región han elegido gobiernos encabezados por simpatizantes del Che—desde el Chile de Salvador Allende en 1970 hasta la Bolivia de Evo Morales y el Ecuador de Rafael Correa, hoy”, deplora la publicación.

El artículo señalaba supuestos efectos negativos para la región derivados de las ideas inculcadas por las luchas del Che y daba su apreciación acerca del gran bienestar continental que el ejemplo del Che había impedido para Latinoamérica.

“Cuando el Che terminó su vida en 1967, el crecimiento de la productividad en América Latina era medio, según consideración mundial. Pero, desde entonces, ha caído por debajo de otras regiones. Solo Brasil y Chile han tenido desempeños aceptables, básicamente gracias a los extensos períodos de gobiernos militares de derecha en los que el Cheismo fue reprimido.”

Luego conjetura: “Sin la leyenda del Che, la tasa anual de crecimiento habría sido un uno por ciento mayor. De ahí que lo que este revolucionario le ha costado a la región es alrededor de $1.3 trillones de crecimiento interno bruto anual.”

Y enfáticamente concluye: “Las camisetas son baratas, pero el Che ha sido un icono caro.”

Las afectaciones para América Latina que el WSJ imputa a las ideas del Che, son en verdad los resultados del desastre económico y social provocado por las políticas neoliberales a cuya implantación forzó Washington a la región en función de su estrategia económica global, luego de haber dependido de dictaduras militares y represión policial con asesoría estadounidense para el ejercicio, durante las dos décadas previas, de su hegemonía imperial en el continente.

La receta de democracia representativa ejercida por partidos políticos controlables por las oligarquías locales en virtud de reglas electorales neoliberales que así lo propician, fue diseñada por Washington cuando se vio obligado a abandonar la fórmula anterior, estimulante de luchas sociales y de la revoluciones armadas como la que triunfó en Cuba hace 50 años y la que el Che preconizó con su ejemplo.

Ahora, el sistema de corporaciones transnacionales de Estados Unidos, cuyos intereses refleja el WSJ, observa con estupor que, con el asesinato del Che, no ha muerto la voluntad y decisión de los pueblos latinoamericanos de obtener la soberanía y la libertad para sus naciones.

Porque si bien la lucha armada era el único camino que dejaba el imperio para la conquista revolucionaria de la soberanía y la libertad para sus naciones, allí donde se ha abierto el camino de las urnas como recurso para la promoción desde el poder de las aspiraciones populares, muchos revolucionarios del continente han aceptado el reto.

Así, en la región se ha conformado un nuevo escenario caracterizado por que, desde hace dos décadas y por primera vez en la historia, se ha hecho muy excepcional la elección de algún candidato a la presidencia promovido o preferido de Washington. Han llegado al poder mandatarios cuyos programas se identifican con los anhelos de sus ciudadanos en una proporción jamás vista antes.

No se trata siempre de dirigentes marxistas o revolucionarios consecuentes—como tampoco lo eran todos los patriotas que antes escogieron el camino de las armas—pero tienen en común el hecho de que proclaman sin ambages la defensa de la independencia de sus naciones y rechazan la subordinación servil a la hegemonía de los Estados Unidos que fuera ley en el continente.

No es que ahora el imperio y las oligarquías se hayan tornado más comprensivos y la lucha de los pueblos se haya hecho más fácil. Nada más lejos de la verdad. La lucha revolucionaria sigue siendo muy difícil porque se libra dentro de sistemas diseñados por las oligarquías con reglas de juego que les propicien ventajas y la supremacía de sus intereses.

La nueva realidad de América Latina, con la revolución cubana imbatida y triunfos electorales de varios mandatarios con programas antioligárquicos que afirman la soberanía de sus naciones es, en muy buena medida, fruto de la rebeldía latinoamericana—de la que el Che es icono—que enfrentó con su lucha las pretensiones de dominio absoluto en la región con que Estados Unidos intentó responder al desafío de la revolución cubana.

Ni qué decir que los pueblos de América Latina no estaban ni estarían jamás dispuestos a soportar tiranías como la de Pinochet, genocidios como el Plan Cóndor y el sometimiento de su dignidad y las soberanías de sus naciones a los dictados de las corporaciones mediante asociaciones como el ALCA, para lograr las tasas de crecimiento económico y demás pírricas ganancias a que alude el WSJ.

Las ideas del Che fueron siempre, incluso cuando se incorporó en México al contingente encabezado por Fidel Castro para luchar contra la tiranía en Cuba, las de una América Latina independiente, unida y socialmente justiciera. Ese ideario maduró y se profundizó en la realidad del combate y en la confrontación con el enemigo mayor, el imperialismo.

Incorporado como médico al contingente de 82 jóvenes en la expedición del yate Granma que desembarcó en Cuba en diciembre de 1956, por su talento táctico y estratégico, así como por su coraje e intrepidez en el combate, el Che pasó a desempeñar un papel cada vez más importante en la guerrilla. Pronto le fue asignada la jefatura de una de las cinco mayores columnas que tenia el Ejército Rebelde y fue el primero en ser ascendido al rango de Comandante que hasta entonces solo ostentaba Fidel Castro.

Como médico en la guerrilla, Che fue paladín de la atención privilegiada a los prisioneros enemigos, práctica que estimulaba la rendición de los militares de la tiranía, convencidos del escrupuloso respeto a los derechos humanos de sus contrincantes cautivos que dispensaban los insurrectos.

Identificado plenamente con los ideales patrióticos cubanos, el Che se convirtió en poco tiempo en uno de los líderes principales de la lucha de liberación y la construcción revolucionaria en Cuba.

A partir de la victoria en la guerra, asumió responsabilidades de dirección en varios campos de la vida civil sin abandonar éstas en el terreno de la defensa.

Se desempeñó como presidente del Banco Nacional de Cuba y como ministro de Industrias y, en el ejercicio de ambos cargos, hizo importantes contribuciones a la teoría y la práctica económicas en esos campos desde las posiciones revolucionarias de una nación en lucha contra el subdesarrollo.

A base de auto estudio, auto preparación y la misma temeridad de que había dado muestras en el combate guerrillero, se convirtió en referente de las posiciones e ideas más avanzadas en diversos aspectos del pensamiento socialista.

Su estilo riguroso de dirigir basado en la autoexigencia, sus críticas punzantes que todos asimilaban por la honestidad que trascendía en ellas, el respeto que inspiraba su entrega total y apasionada al trabajo, y su lealtad a la guía de Fidel Castro, lo llevaron al más alto sitial de la popularidad en Cuba.

Su participación en eventos internacionales y sus contactos con personalidades de naciones del tercer mundo extendieron su prestigio internacional como una de las figuras más representativas de la revolución cubana.

Entre sus cualidades revolucionarios mas significativas destaca su pasión por la justicia, su humanismo, su desprendimiento, su predica constante con el ejemplo y la armónica estructuración que alcanzaron sus ideas políticas, económicas y militares en el breve espacio de una corta vida.

En el campo de las ideas políticas era un marxista convencido que rechazaba el dogmatismo intransigente pretendía despojar el marxismo-leninismo de ataduras doctrinarias congelantes de la revolución y de tendencias burocráticas.

El ejemplo con que predicó el Che la revolución ha dejado mucho más que el mito y la imagen que hoy moviliza a millones de oprimidos, explotados, excluidos y personas insatisfechas con el orden mundial injusto en que viven.

El Che no fue a Bolivia a morir, como no vino a Cuba a morir, ni fue a eso al África antes de emprender el combate en Bolivia. Fue siempre a demostrar con su ejemplo personal cual era la decisión con que debían actuar los pueblos para sacudirse la opresión. Conocía el riesgo y lo asumió plenamente.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: The Sixties

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American Press Association fellowship in 1977. Others—journalist Penny Lernoux and photographer Richard Cross—had also committed much of their lives to Colombia, although their untimely deaths were …

The True Impact of the Peace Corps: Returning from the Dominican Republic ’03-’05

I am an RPCV: a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer. For me the Peace Corps was an intense life experience, above anything else. As I continue to reflect on it, I am struck with the many and varied ways in which it continues to affect my life. As a PCV in the Dominican Republic from September 2003 to November 2005, I lived, worked, and learned in a small sugar cane-dependent community two hours outside of Santo Domingo…

In the Shadow of JFK: One Peace Corps Experience

I am often asked about the Peace Corps by students and recent graduates. The most frequent questions are, “why join?”, “what did you do?”, and “what has it meant for your career?” Here is my story. My earliest recollection of international curiosity was in the fourth grade when Sister Margaret Thomas described her experience as a recently returned missionary in Bangladesh. In high school, my sister Mary went to Peru on …