About the Author

Maria Fernanda Ribeiro Cunha is studying for her Master’s degree in the Department of Social History at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro.

Acerca del Autor

Maria Fernanda R. Cunha é Mestranda do Departamento de História Social da Cultura da Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro.

The Literate Universe and the Pandemic

When my father tested positive for Covid-19 we became a worried, and lost, family. We didn’t know how he had become infected or what we could do to help him get better. I looked for someone who could tell me what to do, sifting through abundance of information that we, who were born the 1990s, grew up with.

It is not big news that, with a click, I found different miracle recipes, promising the best recovery and the best procedures for someone infected with coronavirus. Although nothing could make me feel safe, I have decided to adopt a intuitive way of family care: protect myself as possible and assure that my father ate healthily and was hydrated throughout the day.

My father recovered well and, now that we are beginning to see the numbers of cases of Covid-19 in Brazil falling, we can also see some hope in the efficacy of vaccines in the testing phase. But, until we arrived at that moment, I was in constant doubt about how to take care of my family’s health.

The search for instant answers on the internet for that which is still unknown—like the new coronavirus—is part of an almost natural procedure among my generation. We are used to having the answers in the palm of our hands, in a second. However, this anxiety to discover things we don’t know is not an exclusively contemporary habit. The press and the lettered universe always had an important function in this task of searching for the unknown.

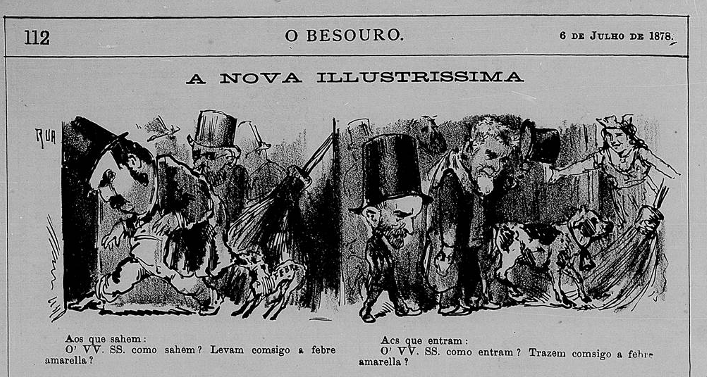

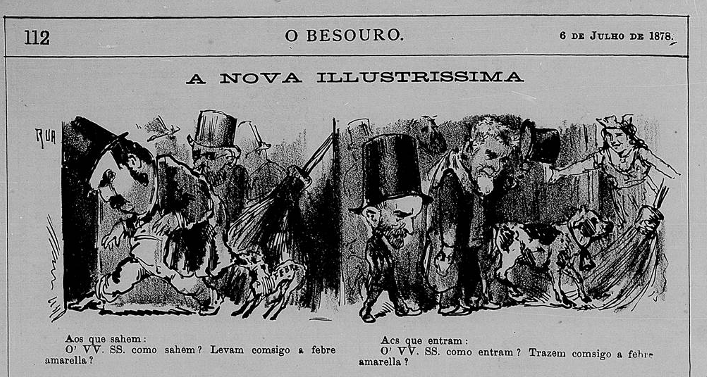

Caricature made by the Portuguese caricaturist, Rafael Bordallo Pinheiro, at O Besouro. In the caption: “To those who leave: Oh, Your Honor, how are you leaving? Are you taking wih you the yellow fever? To those who arrive: Oh, Your Honor, how are you arriving? Are you bringing with you the yellow fever?”. Source: O Besouro, 06/07/1878. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira.

On April 11, 1878, an article in the daily newspaper, O Cruzeiro, tried to answer a lot of doubts about the yellow fever epidemic. The disease that haunted Rio de Janeiro in summers since the early 1850s concerned the Court, particularly because the disease was highly contagious. The author of the article, “Hygiene: the Endogeny of Yellow Fever” asserted that the disease had come from the Gulf of Mexico. Signing as Dr. I. F. dos Reis, the author called upon authorities to reinforce the sanitation of coastal regions, because he believed the epidemic had arrived through the maritime trade.

Doctors specialized in sanitation believed that the public housing, like the cortiços (tenements), represented the most dangerous hotbed of contagions, because the poor living conditions of these places facilitated the proliferation of diseases. Not knowing that the yellow fever was transmitted by the bite of the mosquito Aedes aegypti, the measures focused on hygiene and increased surveillance of lower-class communities.

In Bolsonaro’s Brazil, it is also possible to observe how living conditions can change the reality of patients with Covid-19. The working class suffers from abandonment, receiving emergency aid just a little bit more than the half the minimum wage.

Exame magazine had pointed ut that, as soon as the first cases of the disease appeared in Brazil, that 44% of the intensive care (ICU) beds in the country are in the Brazilian Health System (SUS) and the other 56% in the private network. However, 75% of the Brazilian population depends on the public health system. The collapse was obvious, although the SUS does provide free medical assistance.

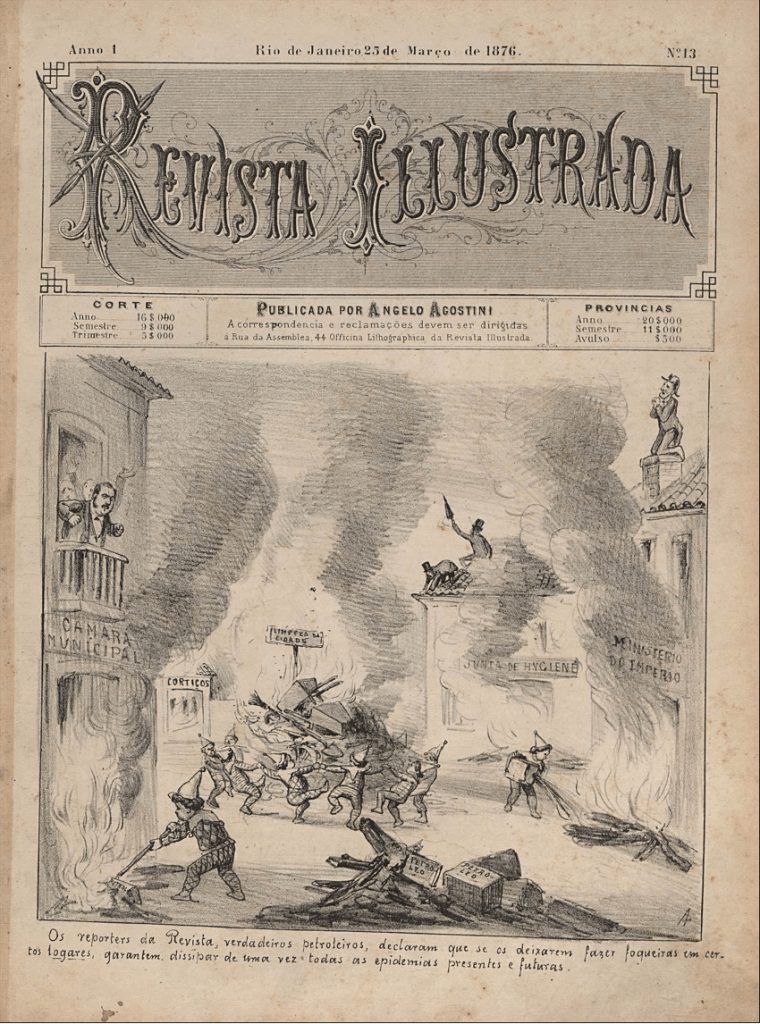

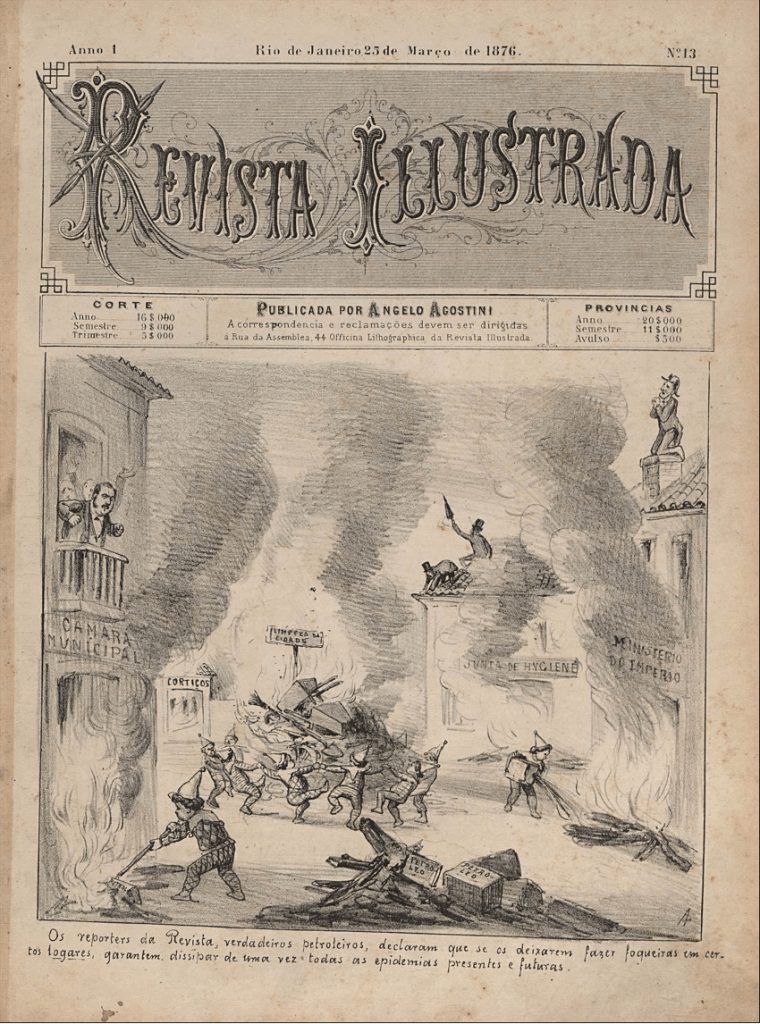

On the cover of the March 23, 1876, edition of Revista Illustrada, the Italian caricaturist Ângelo Agostini draws the cortiços, the hygiene joints, the ministery of the Empire and the town hall burned, for the end of the epidemics of yellow fever. In the caption: “The magazine reporters, true tankers, declare that if they let them make fires in certain places, they guarantee to dissipate at once all the present and future epidemics.” Source: Revista Illustrada, 23/03/1876. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira.

With my father’s situation, I was in search of information. Brazil has not even had a Minister of Health for more than a hundred days. I search obsessively in the media for ways to be informed. I find some information from the World Health Organization, with international protocols, and then I encounter supposedly miraculous recipes on kooky sites that float around the social media. Underestimating science and medicine, many deniers promise to have found the cure for Covid-19 in homemade syrups, thus encouraging the end of social isolation.

The denialism, in this way, seems to be a consequence of Jair Bolsonaro’s discourse, widely reproduced in social media, that mobilizes the part of the population that still believes in the president. And, like in the 19th century, we’re drowned in the relation between the medical science and the media, before print and now, mostly digital platforms.

Still in the lettered universe, the fantasy and the fiction may seem like a refuge to the chaotic and uncertain reality of the health crisis in Brazil. Dystopic narratives, romances and comics still give us tools to understand the pandemic world that we are living. However, researchers point out that Brazil’s book market faces a recession, during the pandemic. According to Nielsen Media Research, published by Época magazine in July, book sales accumulated a loss of 13% over the same period in 2019.

Meanwhile, literary characters still can manage to translate real and collective feelings around the reality. More than the life imitating art, we have the art imitating life. And, just like Tita, from the romance Como água para chocolate by Mexican novelist Laura Esquivel, I tried to heal my family and myself with a large porridge of cornmeal with spices.

Brás Cubas, the defunct storyteller of Machado de Assis,wanted to see all diseases healed through the use of a patch. Ironically, he dies from pneumonia and presents us with his own story starting with his death, but doesn’t fail to revive in his posthumous memories the love stories that he lived, to the sound of cities and the flavor of the encounters.

Advertisement for medicines and medicinal syrups. Source: A Estação, 31/08/1898. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira.

After a long time, distant from these meetings, our tiredness leaves us just the hope. Are we all waiting for just one patch that can restore health to the more than four million people infected with Covid-19 in our country?

O Universo Letrado e a Pandemia

Por Maria Fernanda Ribeiro Cunha

Quando meu pai testou positivo para a Covid-19 nos tornamos uma família preocupada e perdida. Não sabíamos como ele havia se infectado e nem o que faríamos para vê-lo melhor. Procurei alguém que pudesse me dizer o que fazer, na chuva de informações em que nós, nascidos nos anos 1990, nos alfabetizamos.

Não é novidade que, com um clique, acessei diferentes receitas milagrosas, prometendo a melhor recuperação e o melhor procedimento com uma pessoa infectada com o novo vírus. Embora nada pudesse me fazer sentir segura, decidi adotar uma maneira mais intuitiva de cuidado familiar: me proteger o máximo possível e garantir que ele se alimentasse bem e se hidratasse ao longo do dia.

Meu pai se recuperou e, agora que começamos a ver os números de casos de Covid-19 caírem no Brasil, nós podemos também ver alguma esperança na eficácia de vacinas em fase de teste. Mas, até chegarmos a esse momento, eu estava em constante dúvida acerca da maneira com que deveria cuidar da saúde da minha família.

A procura por respostas instantâneas na internet para aquilo que ainda é desconhecido, como o novo coronavirus, faz parte de um movimento quase natural entre os nascidos na mesma época que eu. Nos acostumamos a ter respostas na palma da mão,

Caricatura feita pelo caricaturista português Rafael Bordallo Pinheiro, no periódico satírico O Besouro. Na legenda: “Aos que saem: Ó, Vossa Senhoria, como saem? Levam consigo a febre amarela? Aos que entram: Ó, Vossa Senhoria, como entram? Trazem consigo a febre amarela?” Fonte: O Besouro, 06/07/1878. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira.

em fração de segundos. No entanto, essa ansiedade de descobrir sobre algo que não conhecemos não é algo exclusivamente contemporâneo. A imprensa e o universo das letras sempre tiveram papel importante nesse exercício de buscar saber sobre o desconhecido.

Caricatura feita pelo caricaturista português Rafael Bordallo Pinheiro, no periódico satírico O Besouro. Na legenda: “Aos que saem: Ó, Vossa Senhoria, como saem? Levam consigo a febre amarela? Aos que entram: Ó, Vossa Senhoria, como entram? Trazem consigo a febre amarela?” Fonte: O Besouro, 06/07/1878. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira.

No dia 11 de abril de 1878, um artigo no jornal O Cruzeiro tentava responder perguntas a respeito das epidemias de febre amarela. A doença, que assombrou o Rio de Janeiro nos verões a partir dos primeiros anos da década de 1850, causava ansiedade nos moradores da Corte, sobretudo em relação ao contágio. Para o autor do artigo, intitulado “Higiene: endogenia da febre amarela”, a doença teria sido importada do Golfo do México. Assinando como Dr. I. F. dos Reis, o autor reclamava às autoridades que reforçassem a sanitarização das regiões litorâneas, por acreditar que a epidemia tivesse chegado por meio das importações comerciais.

Médicos especialistas na sanitização acreditavam que as habitações coletivas, como os cortiços, representavam maior perigo de contágio, o que pode se explicar por meio das condições precárias da vida nesses lugares, que facilitavam a proliferação de doenças. Não sabendo que a febre amarela era transmitida por meio da picada do mosquito Aedes aegypti, as teorias a respeito da epidemia davam brecha para uma série de medidas higienistas, que tinham como preceito o controle da vida das comunidades de pessoas de classes mais baixas.

No Brasil de Bolsonaro também é possível observar como as condições sociais podem mudar a realidade de pacientes com Covid-19. A classe trabalhadora sofre com o abandono, recebendo um auxílio emergencial apenas um pouco maior do que a metade do salário mínimo.

A revista Exame havia apontado, logo que os primeiros casos da doença apareceram no Brasil, que 44% dos leitos de UTI no país estão no Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS) e os outros 56% na rede privada. Sendo que 75% da população brasileira depende da rede pública de saúde. O colapso era óbvio, embora o SUS seja referência de assistência médica gratuita.

Na capa da edição da Revista Illustrada, de 23 de março de 1876, o caricaturista Ângelo Agostini desenha os cortiços, as juntas de higiene, o ministério do Império e a Câmara Municipal incendiados, em prol do fim das epidemias de febre amarela. Na legenda: “Os repórteres da Revista, verdadeiros petroleiros, declaram que se os deixarem fazer fogueiras em certos lugares, garantem dissipar de uma vez todas as epidemias presentes e futuras”. Fonte: Revista Illustrada, 23/03/1876. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira.

Com a situação enfrentada pela minha família, estive procurando por informações. O Brasil não tem sequer ministro da saúde, há mais de cem dias. Precisei procurar obsessivamente nos meios de comunicação maneiras de me manter informada. Encontrei algumas recomendações da Organização Mundial da Saúde (OMS), com protocolos internacionais, e também receitas supostamente milagrosas em sites excêntricos que flutuam nas mídias. Subestimando a ciência e a medicina, muitos negacionistas prometem ter encontrado a cura para a Covid-19 em xaropes caseiros, encorajando, portanto, o fim do isolamento social.

O negacionismo, dessa forma, parece ser consequência do discurso de Jair Bolsonaro, amplamente reproduzido nas mídias sociais, que mobilizam a camada da população que ainda acredita no presidente. E, bem como no século XIX, estamos mergulhados na relação entre as ciências da saúde e os meios de comunicação, antes impressos e agora, em sua maioria, digitais.

Ainda no universo das letras, a fantasia e a ficção podem parecer um refúgio para a realidade caótica e incerta da crise sanitária no Brasil. As narrativas distópicas, os romances, as histórias em quadrinhos ainda dão instrumentos para a compreensão do mundo pandêmico que estamos vivenciando. No entanto, as pesquisas apontam que o mercado de livros no país enfrenta uma recessão durante a pandemia. De acordo com pesquisa da Nielsen Media Research, divulgada pela Revista Época em julho, a venda de títulos acumula uma perda de 13% em relação ao mesmo período no ano de 2019.

Enquanto isso, personagens da literatura ainda conseguem traduzir sentimentos coletivos e reais em torno da realidade. Mais do que a vida imitando a arte, temos a arte imitando a vida. E, assim como Tita, do romance Como água para chocolate, da autora mexicana, Laura Esquivel, quis tratar minha família e a mim mesma com um caudaloso mingau de fubá e especiarias.

Brás Cubas, o narrador-defunto de Machado de Assis queria ver curadas todas as doenças com seu emplasto. Ironicamente sucumbe a uma pneumonia e nos apresenta a própria história a partir de sua própria morte, mas não deixa de reviver em suas memórias póstumas os romances que viveu, ao som das cidades e ao sabor dos encontros.

Anúncio de remédios e tônicos medicinais. Fonte: A Estação, 31/08/1898. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira.

Depois de tanto tempo distantes desses encontros, nosso cansaço nos reserva a esperança. Estaríamos, todos nós, apenas esperando um emplasto capaz de devolver saúde aos mais de quatro milhões de infectados por Covid-19 em nosso país?

More Student Views

Puerto Rico’s Act 60: More Than Economics, a Human Rights Issue

For my senior research analysis project, I chose to examine Puerto Rico’s Act 60 policy. To gain a personal perspective on its impact, I interviewed Nyia Chusan, a Puerto Rican graduate student at Virginia Commonwealth University, who shared her experiences of how gentrification has changed her island:

Beyond Presence: Building Kichwa Community at Harvard

I recently had the pleasure of reuniting with Américo Mendoza-Mori, current assistant professor at St Olaf’s College, at my current institution and alma mater, the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Professor Mendoza-Mori, who was invited to Madison by the university’s Latin American, Caribbean, and Iberian Studies Program, shared how Indigenous languages and knowledges can reshape the ways universities teach, research and engage with communities, both local and abroad.

Of Salamanders and Spirits

I probably could’ve chosen a better day to visit the CIIDIR-IPN for the first time. It was the last week of September and the city had come to a full stop. Citizens barricaded the streets with tarps and plastic chairs, and protest banners covered the walls of the Edificio de Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca, all demanding fair wages for the state’s educators. It was my first (but certainly not my last) encounter with the fierce political activism that Oaxaca is known for.