The Naked Emperor of the Southern Cone

Pinochet and the New Chile

On a hot and dusty January day in Santiago de Chile, I was riding in my host father Alberto’s pickup truck, passing the large factories and ramshackle homes that line the city’s north border, when I heard something on the radio about a Chilean military declaration regarding the Pinochet dictatorship. I was in Chile for only two weeks to conduct research for my senior thesis, exploring how the Pinochet case had affected Chile’s re-democratization process. I immediately asked Alberto what had happened. “Oh,” he responded, “Army chief Emilio Cheyre has just made an announcement in which he condemned human rights violations of the past and proclaimed that the Army belongs equally to all Chileans.” My jaw dropped at the timeliness of this event; the last thing I expected, over four years after Pinochet’s arrest in London, was an important moment in the history of the Pinochet case.

This event highlighted one of the most salient facts I’ve learned about the Pinochet case: it means radically different things for Chileans and non-Chileans. The image and legacy of Augusto Pinochet are indelibly intertwined with the triumph and tragedy of modern Chile. Thus, his international downfall would inevitably have serious implications for this nation, regardless of the case’s impact on the rest of the world. Of course, Pinochet’s arrest did change international standards, in ways that validated those who have clamored for domestic justice for human rights abusers, as well the concept of “universal justice” in national courts. The Pinochet precedent has become increasingly accepted, particularly in Latin America and Europe. Mexico’s extradition of Argentine naval officer Ricardo Cavallo to Spain, and Argentine President Nestor Kirchner’s decision this July to permit the extradition of that nation’s most notorious “Dirty War” criminals are recent examples. These men face justice from the same Judge Balthasar Garzón who indicted Pinochet himself.

Despite intense press coverage, most people do not have a realistic view of what happened in Chile after Pinochet’s return, nor the effects of the arrest on the nation’s democracy. I personally was shocked when, researching the case for a seminar paper, I learned that Pinochet had been arrested upon his return in Chile. I had been certain the government’s prior claims that Pinochet could be tried at home were disingenuous at best. Although Pinochet never went to prison in Chile, it was only because he was found unfit to stand trial due to alleged senility. His defense never argued that Pinochet was not guilty of the crimes as charged, and public opinion solidly agreed with his domestic trial. I became fascinated with the international impact of the arrest and its implications within Chile itself—an encouraging story for democratization and justice.

DISSECTING TWO MYTHS

Many Chileans and Americans familiar with this topic told me about two mistaken ideas regarding the domestic political impact of the Pinochet case. The first is that the arrest of Pinochet represented a threat to the re-democratization process, a viewpoint famously articulated by Harold Muñoz and Ricardo Lagos (now Chile’s president) in Foreign Policy and Chile’s El Mercurio in 1999. Secondly, while Pinochet languished in London, observers began to notice that judicial independence in Chile was actually increasing, reflecting a newfound willingness to address human rights issues. Many Chilean and international scholars credited the British and Spanish legal systems and their political pressure, showing mostly contempt for the Chilean judiciary and domestic politicians’ efforts to increase democracy and address the human rights question.

DISMANTLING PINOCHET’S AUTHORITARIAN ENCLAVES

When Augusto Pinochet handed the Chile’s Presidential sash over to Patricio Aylwin on March 11, 1990, he did so reluctantly and with open contempt for the incoming democratic system. Forced to leave the presidency after defeat in a national plebiscite on his rule, Pinochet endured another defeat when his handpicked successor, Hernan Buchi, lost the following Presidential election to Aylwin. Chile’s return to democracy was assured.

However, military authorities soon designed a plan to restrict the reach and authority of democratic actors. Pinochet was always distrustful of what he called “musty” democratic institutions, and wanted to create a protected democracy. Essentially, Pinochet and his allies hoped to keep the new regime as similar to the old regime as possible. They created checks on civilian power that came to be known as authoritarian enclaves, explained as an “interlocking system of non-democratic prerogatives” by Juan Linz and Alfred Stepan in 1993. This included bastions of authoritarian power built into the constitution, such as appointed Senators, preservation of the Amnesty Law of 1978 (which protects human rights violators), and continuation of a power base around Pinochet and other authoritarian actors.

Amazingly, Chile today operates under the same constitution written and promulgated during Pinochet’s dictatorship. Pinochet was able to maintain this balance of power because significant portions of the public considered the outgoing regime to be a “successful” military dictatorship for wiping out Marxist opposition and fostering economic growth. Gross human rights violations of torture, murder and disappearances were almost exclusively committed against politically active leftists and mostly did not affect the general population, as in other Latin American dictatorships. Thus, it was easier for the government to deny or justify these actions and for the public to ignore them.

Despite dual losses for the military authorities in 1988 and 1989, Pinochet and his allies still held a great deal of influence at the outset of the new democracy. Pinochet became Commander-in-Chief of the Army, a position protected by the Organic Laws, which were enacted to protect the autonomy of the military institution. He also issued an explicit threat against the incoming government, stating that the day he or one of his men was touched, the rule of law would end. Despite this serious peril, from the moment of Aylwin’s inauguration, civilian authorities worked to increase the regime’s democratic nature and to redress past human rights abuses as best they could.

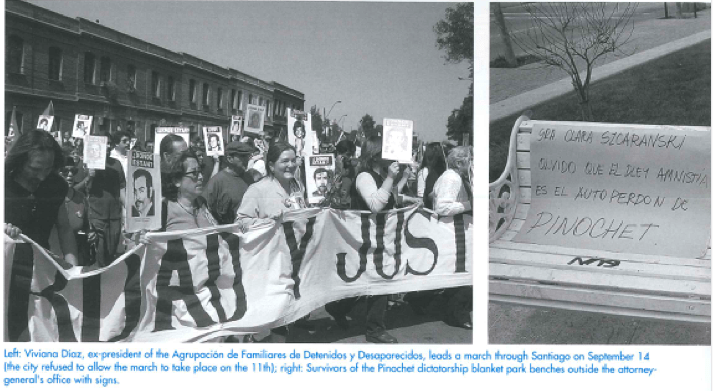

In April 1990, President Aylwin created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which conducted a highly professional and detailed investigation and documented more than 3,000 serious human rights abuses perpetuated by the Pinochet regime. When human rights activists first learned that the word “Justice” was lacking from the commission’s title, they were disheartened, noted Viviana Diaz, former president of the Association of Families of the Disappeared. The Commission had no authority to prosecute anyone. But today virtually all Chileans—from hardened human rights activists to those on the ideological right—acknowledge that the Commission was an important step forward in the Chilean reconciliation process.

Immediately before leaving office, Pinochet had stacked the Supreme Court with justices who would be loyal to him, attempting to perpetuate the highly subservient role the judiciary had played throughout his dictatorship. Under intense pressure from Chilean human rights organizations, the courts began to require the full investigation of a crime before the application of the Amnesty Law. As time progressed, more and more judges were appointed by the civilian government, and after several years things shifted in regards to human rights trials. Most importantly, Manuel Contreras, the former head of Pinochet’s secret police, was convicted in June of 1995 of conspiracy in the murder of prominent exile Orlando Letelier. After his conviction he was spirited away to a naval hospital, where a standoff ensued. In the end the military caved, and even though this case had been exempted from the Amnesty Law, it still showed Pinochet’s previous threat to be hollow. After this conviction a steady trickle of human rights criminals joined Contreras at the special prison built for him in Punto Pueco, with more cases pending each day.

A CATALYST FOR CHANGE

After Pinochet’s 1998 retirement as Commander-in-Chief, he kept his immunity by assuming the position of Senator-for-Life. At this point most Chileans expected him to live out his days quietly, although he still cast a powerful shadow over the new democracy. But instead he chose to have tea with Lady Margaret Thatcher and undergo back surgery in London, not believing that a Spanish judge named Garzón represented a true threat to him. His October 16, 1998 arrest was met with complete incredulity in Chile. No one—left, right or center—could believe that this fearsome and omnipotent dictator was now a prisoner who might have to face trial for crimes against humanity.

A new sense of urgency was given to the processes of redressing the past human rights violations. While the courts had gradually become more willing to prosecute and punish for human rights crimes, the arrest accelerated this process, led by Judge Juan Guzman’s significant ruling that disappearances could be considered “perpetual kidnappings” and therefore extend past the Amnesty Law’s cutoff point. Equally important, the then-ruling government of Eduardo Frei initiated theMesa de Dialogo, a forum in which human rights advocates, religious figures, and military leaders would sit down and discuss past and present human rights issues. This Mesa sought to both obtain information on the whereabouts of the bodies of the disappeared and to get the military to admit its culpability for human rights violations. In the first aspect, the Mesa failed completely. However, in the second it was such a success that Mesa participant Jose Zalaquett referred to it as a “civic sacrament.” The Mesa’s dual goals explain the human rights community’s disparate views regarding its success. More radical activists denounced the Mesa as the legitimization of an “institutional lie,” while others view it as a crucial step towards accepting the truth about past human rights abuses.

After Pinochet’s detention, the Chilean right initially rallied around “the jefe,” defending Pinochet’s record and casting the prosecution as a socialist conspiracy. However, when I recently asked prominent conservative advisor Marco Antonio González of the Jaime Guzmán Foundation if he still considered Pinochet the leader of Chile’s right, he compared my question to him coming to the United States and asking Republicans about Richard Nixon. That was part of Chile’s past, he said; the right is concerned about Chile’s problems today; it is the left that needs Pinochet—to keep him around as a symbol.

THE EMPEROR’S NEW CLOTHES

When Pinochet returned to Chile in March 2000, it became evident that his international disgrace had destroyed his domestic image. Although he was received with full military honors, his first act was to stand up from his wheelchair and defiantly raise his cane in the air, in an attempt to recapture his “superman” image. This gesture, which disclosed that his health defense was a lie, shocked and offended a great majority of the Chilean public. Soon Pinochet was back in court, charged with more than 300 cases of human rights violations. The prosecution successfully stripped Pinochet of his immunity as a Senator-for-Life, but once again Pinochet escaped jail time after citing his age and alleged mental incapacity. Although Pinochet will never face jail time, even the once supremely loyal Chilean military has distanced itself from him and the dictatorship. In the Mesa’s June 2000 report, military representatives publicly admitted responsibility for human rights violations and declared that such acts were inexcusable. This fact was further emphasized by Cheyre’s 2003 declaration.

In the end though, what is the relevance of Pinochet’s arrest? In light of the progress that Chileans had been making between 1990 and 1998, it is plausible that the arrest simply served as a catalyst by accelerating the processes in effect since Aylwin assumed the Presidency. This was the opinion expressed by Zalaquett, who said that many of these processes would have happened without the arrest, maybe less so and more slowly, but they would have happened. In my opinion, however, something about the arrest itself set off a genuine and powerful psychological reaction in the Chilean consciousness. For years, Pinochet had been revered and reviled, but after crushing opponents, surviving upheaval and assassination attempts, he was universally viewed as the Untouchable. But then he blundered into the hands of the British and ended up at the mercy of a foreign court, creating a situation that was more than humiliating. The arrest was, according to scholar Gregory Weeks, a symbolic death. Pinochet could perhaps have survived this mistake, but his pleas of infirmity and incapacity sealed his fate. The Emperor was revealed to be naked, and his once-imposing image could not hold the same sway over the Chilean people and their democracy ever again.

Fall 2003, Volume III, Number 1

Jonathan Taylor ’03 graduated from Harvard in June with a bachelor’s degree in government and a Latin American studies certificate. He is currently working for Poder Ciudadano in Buenos Aires, and in January will go to work for IDL in Lima. For a much, much longer discussion of this article, write to him at jonathan_taylor@post.harvard.edu.

Related Articles

Human Rights: Editor’s Letter

During the day, I edit story after story on human rights for the Fall issue of ReVista. During the evening, I work on my biography of Irma Flaquer, a courageous Guatemalan journalist who was…

ONGs en América Latina y los derechos humanos

Las ONG ofrecen mil modos de recordar la dignidad humana a los gobiernos y las sociedades. Las dos experiencias que esbozo en esta nota reflejan algunas de las estrategias asumidas por…

Peru’s Human Rights Coordinating Committee

The human rights abuses that devastated Peru from the early 1980s to the mid 1990s are once again an issue of debate in that country with the release of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation’s…