The Overlapping Geographies of Resource Extraction

Four months, three decisions, one pattern?

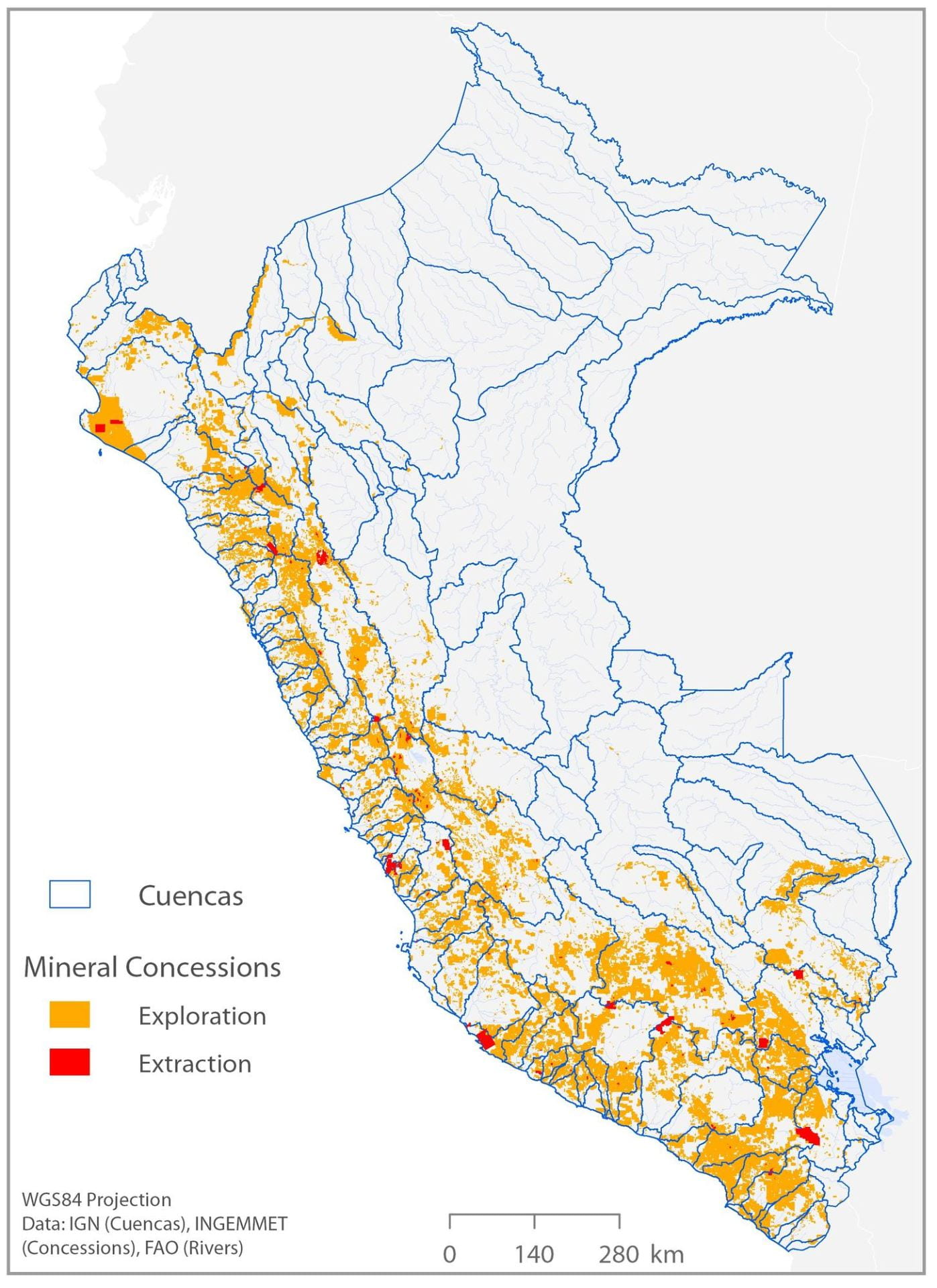

Map overlaying the geography of mining concessions and the geography of drainage basins in Peru. Map courtesy of Anthony Bebbington.

On May 23, 2013, Vice President Alvaro García Linera announced that Bolivia would promote drilling for hydrocarbons inside protected areas. His statement projected the image of a sovereign, ecologically modernizing and necessary extraction: an extraction for Bolivian development, by the Bolivian state, protecting Bolivia’s environment. Associating existing protected areas with non-sovereign interests, he commented that it was “not by chance that national parks have been declared in a good part of these oil- and gas-rich zones, preventing us from exploring them and doubtless protecting these resources for someone else.” He continued, “We are going to use (the resources) ourselves, with due care, with due capacity to mitigate environmental impacts, with the care needed to protect the natural structure of the forests, mountains and rivers, spending as much money as is necessary to guarantee this mitigation: it is incumbent on us Bolivians to use this wealth.”

Two short months later, in July 2013, the Peruvian government overrode its own Ministry of Culture, which had expressed concerns that designs for an expansion of the Camisea gas project into protected areas would threaten the well-being of indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation. There were clear echoes here of an argument that then-President Alan Garcia had made several years earlier: “Against oil, they have created the figure of the ‘non-contacted’ jungle native, unknown but presumed to exist, on whose account millions of hectares must not be explored, and Peruvian oil has to stay underground.” Then came another case, on August 15, 2013, as Ecuador’s President Rafael Correa completed an Andean hat-trick and announced that oil drilling would proceed inside the Yasuní National Park, another protected area occupied by indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation (http://www.bbc.co.uk/go/em/fr/-/news/world-latin-america-23722204). This third decision was especially dramatic, as Yasuní had been the object of an internationally recognized experiment in which the world would have paid Ecuador not to exploit the oil in recognition of the inherent cultural, biophysical and climatic impacts that such extractions would imply.

Although these decisions relate to a different extractive industry, that of gas and oil, both the decisions and their justifications are highly relevant for mining and other exploitation of natural resources in the region. Ecuador’s President Correa and his ministers have used two arguments to justify their government’s position. First, that the decision to go into Yasuní was the responsibility of the international community, which had not stepped up with the resources to compensate Ecuador for leaving the oil in the ground and, second, that the country’s poverty reduction needs were so great that, absent this compensation, he could not afford to leave the oil in the ground—the revenue was needed to finance social development. A few years earlier, on October 7, 2009, Bolivia’s President Evo Morales had said something similar: “What, then, is Bolivia going to live off if some NGOs say ‘Amazonia without oil’? ….They are saying, in effect, that the Bolivian people ought not to have money, that there should be neither IDH [a direct tax on hydrocarbons used to fund government investments] nor royalties, and also that there should be no Juancito Pinto, Renta Dignidad nor Juana Azurduy” [cash transfer and social programs]. In Peru the emphasis was slightly different. Minister of Energy and Mines Jorge Merino simply declared that there were no contacted indigenous peoples in the area into which Pluspetrol, the operator of Camisea, would expand, and that therefore there was no need for any process of prior consultation. Both government and company argued that environmental risks could be mitigated.

There are many ways of making sense of these decisions. They can be seen as legitimate manifestations of sovereign power exercised by democratically elected governments. These political leaders have each invoked sovereignty to justify their decisions and question the legitimacy of their critics. These justifications can also be seen as one more formulation of the argument that “growth is good for the poor” (the title of David Dollar and Aart Kray’s widely cited defense of economic growth). The belief that natural resource extraction will generate wealth that will help “the poor” is pervasive, even though the evidence that oil and mining revenues necessarily enhance their well-being is decidedly mixed, and certainly the social and infrastructural spending triggered by Ecuador’s last round of oil-led growth in the 1970s proved unsustainable. Third, these different decisions and justifications can be interpreted as one more indication that 21st-century socialism and 20th-century neoliberal capitalism approach the governance of natural resource extraction in strikingly similar ways. They are also further examples of how institutions are “flexibilized” in order to allow drilling and mining, a pattern in which the rules of the game are always shifting, and where, despite efforts to introduce environmental and social safeguards, these seem ultimately to be softened to accommodate extraction. In the words of Peru’s former Minister of Culture, Luis Peirano, “the idea of the government and the Office of the Executive is that there should be no obstacles or impediments to investment” (as quoted by Paola Arica in the Peruvian publication La Revista Agraria).

The ways in which such decisions are justified resonate with broader claims made in theories on development and sustainability. Decisions about extraction are consistently framed as responses to the urgent need to reduce poverty and finance social policy. Less attention is paid to the precise mechanisms through which this poverty reduction will occur, while potential purposes motivating these decisions go unspoken. These silences remind us of arguments that have been made by Colombian anthropologist Arturo Escobar, among others, that we must always be attentive to what is done “in the name of development” and that very frequently the notion of development is invoked in order to justify decisions that are really about something else. This does not mean going so far as to argue that “development” is always “destruction,” but it is important to recognize that the language of development can all too easily be used to justify destruction in the service of some greater good. This is one of the arguments that the Uruguayan social ecologist and commentator, Eduardo Gudynas, has been making in recent years, as he has established himself as one of the most trenchant critics of Latin America’s commitment to large-scale resource extraction, industrial agriculture and mega-infrastructure. Gudynas constantly reminds his audience of all that is being risked and traded in as governments of the region rush for the subsoil.

In a related vein, it might be argued that underlying such decisions is a notion of democracy as a problem of arithmetic more than one of fundamental rights. Of course it is true that the number of people who will benefit from the taxes generated by natural resource extraction will far exceed the number of indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation who will be adversely affected. It is also very likely to exceed the number of indigenous and other people whose livelihoods and territorial claims might be compromised. The question that is not asked, however, is whether one person’s right of access to education and health services is equivalent to another person’s right to existence, to an ethnic group’s collective right to territory or, even, to nature’s right to existence. Posing this question does not mean that one automatically concludes that these latter rights (to existence, territory, identity) necessarily trump rights of access to social services. It does mean that this question about how to discuss, agree upon and legitimize trade-offs among these different sorts of rights has to be addressed head on and debated seriously in the public sphere. To the extent that these discussions are elided (and they often seem to be in these presidential interventions), then the quality of democracy is impoverished and space is created for development strategies that can systematically privilege some social, racial and ethnic groups over others.

At the same time as these resource extraction decisions are being framed within particular discourses of development and democracy, they are also being framed within discourses of care and technological modernity. In this sense they are part of a larger argument about “ecological modernization,” which claims that with the appropriate technology and institutions, economic growth can accompany, and be a vehicle for, environmental protection and restoration. We see this in the García Linera quotation introducing this article, as well as in the way that Rafael Correa couched his Yasuní decision, saying that oil exploration would leave most of the park untouched, affecting less than one percent of its area (to quote the BBC). Spokespersons for Pluspetrol, the operator of the Camisea project, likewise said that their plan to expand operations “far and away satisfies Peruvian laws and international standards” and that “these are high level standards against which Camisea has performed successfully during these ten years of working in the area and of serving as an outstanding example internationally.”

OVERLAPPING GEOGRAPHIES

While these three cases are particularly poignant, involving areas of great biodiversity and indigenous peoples who in some instances live in voluntary isolation, they are really just the sharp end of a broader phenomenon associated with the expansion of extractive industries—a phenomenon of “overlapping geographies.” In these cases the expansion of natural resource extraction overlaps with areas already demarcated as “protected” and in some instances occupied by groups opting to live in isolation. In other cases, mining and hydrocarbon concessions overlap areas occupied and used by indigenous and/or peasant communities, by pastoralists or by market-oriented farmers. They also overlap with areas on which urban settlements depend for their water resources. More than spatial overlaps in a simple descriptive sense, these can also be viewed as “overlapping geographical projects.” That is to say, there are different ideas at play here regarding who should occupy particular spaces, who should govern and control what goes on in those spaces, whose symbols should be visible in those landscapes, and who should have access to the land, water and biogeographical resources existing in those spaces. Thus, geographical projects that are often unselfconscious and taken-for-granted become very definite when they are challenged by other projects that are based on other ideas of who should control space and access resources.

Over the last decade or so, a number of Latin American, North American and European organizations and scholars have explored ways of mapping these overlapping geographies. They have sought to give visual expression to supranational, national, subnational and really quite local forms of overlap, and have also explored different types of overlaps. They have mapped overlaps between mining licenses and water resources (Figure 1), hydrocarbon concessions and indigenous territory (Figures 2 and 3), mining concessions and rural communities, and natural resource concessions and protected areas (Figure 3). Maps have also honed in on specific drainage basins, and zoomed out to give a sense of the overall geography of environmental costs produced by extraction, while others are trying to give visual expression to the flows of tax revenue generated by extraction.

The goal of such visualizations is to communicate dimensions of the extractive economy that are not adequately conveyed by text, graphs or tables. The underlying idea is that the spatial dimension communicates something specific and unique, and it is often the case that as soon as such maps are projected, the audience’s intake of breath is at once sharp and audible. The question, however, is whether such visualizations are adequate vehicles of communication. Indeed, we have often heard officials criticize such maps of concessions on the grounds that they vastly overstate the significance of extraction. Such critics argue that only a very small area of a mining or oil or gas concession is ultimately converted into pits, tunnels, wells, pipelines and other operational infrastructure. This, of course, is true. However, these concession maps still communicate many things that are important.

First, the visualizations show the overlapping geographies that those actors who are driving the extractive economy are willing to countenance as they seek out minerals and hydrocarbons. That is, they draw attention to development trade-offs that decision makers are at least willing to consider. Second, they reveal the geographies of uncertainty produced by the extractive economy. When a local population finds out that the subsoil beneath them has been subject to a concession (and they generally find out after the fact because they are very rarely consulted beforehand), then a great deal changes. Visions of the future change dramatically and begin to incorporate a raft of new potential losses and gains, all imagined on a relatively large scale (lots of jobs, lots of pollution, big roads, bigger holes in the ground). This sense of uncertainty (and all its attendant risks and opportunities) has been a recurrent theme in the fieldwork that I and my colleagues and students have done over the last few years in Peru, Bolivia, El Salvador, Ecuador and Colombia. The national maps of exploration licenses and contracts give a sense of just how widely this uncertainty extends, while the subnational maps help draw attention to its particular dimensions in specific places (“what does this mean for our water?” “what will happen to our territory?”). Meanwhile, a large literature on social protest helps us understand the different ways in which this uncertainty contributes to conflict and social mobilization.

Third, maps such as these make visually explicit the existence of governance systems that produce overlapping and potentially contradictory claims on, and rights in, natural resources. They help to show which of these systems are more and less coordinated. For instance, systems granting rights to explore the subsoil and systems delineating protected areas seem to be better coordinated. There are fewer overlaps between national parks and mineral concessions, and indeed the three cases introduced at the start of the article have become contentious precisely because the normal practice has been to avoid overlaps between extractive industries and protected areas. Conversely, there seems to be far less coordination between the governance of extractive industry and that of water and agricultural resources, the result being significant overlaps between areas in which extractive industry has been given rights and areas that are important for water resources and agricultural production. The maps do not tell whether the reasons for this lack of coordination are inefficiency, information constraints, a policy or political commitment to prioritize resource extraction over other activities and needs, the lack of politically organized constituencies to demand coordination, or some other reason. But they do help pose the question quite forcefully.

Visualizations such as these are also one way of showing how the construction of any particular territory as well as the construction of a nation state depends on the ways in which different geographical projects are combined and negotiated. These “projects” imply different ways of controlling and using natural resources and of occupying and governing space. They imply the presence of different social actors at the helm of such projects, and different ways of producing wealth. As these projects meet, one may dominate others or they may negotiate modes of coexistence. The expansion of extractive industries is one such geographical project—and a particularly powerful one. How it ends up interacting, mediating and negotiating with other geographies and geographical projects is already proving to be an important factor in the refashioning of nation, territory and the state in Latin America. In this sense, the political significance of mining, oil and gas is immense.

Winter 2014, Volume XIII, Number 2

Anthony Bebbington is the Milton and Alice Higgins Professor of Environment and Society and Director of the Graduate School of Geography, Clark University. He is also a Professorial Research Fellow, Institute of Development Policy and Management (IDPM) at the University of Manchester.

Nicholas Cuba is a doctoral student in the Graduate School of Geography, Clark University.

John Rogan is Associate Professor in the Graduate School of Geography, Clark University.

Related Articles

Making a Difference: Building Blocks

Since the first, unplanned visit of a Brazilian entrepreneur in 2011 to Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child, a diverse group of professors, practitioners, civil society leaders and other committed individuals at Harvard and in Brazil have…

Travails of a Miner, VIP-style

English + Español

Sergio Sepúlveda is a Chilean miner with an enviable salary—equivalent to that earned by a university-educated professional. He owns a brand new Korean-made car, and every three years…

Indigenous People and Resistance to Mining Projects

English + Español

Latin America’s governments and its indigenous peoples are clashing over the issue of mining. Governments, motivated by economic growth, have established legal frameworks to attract foreign investments to extract mining resources. When those resources are located in…