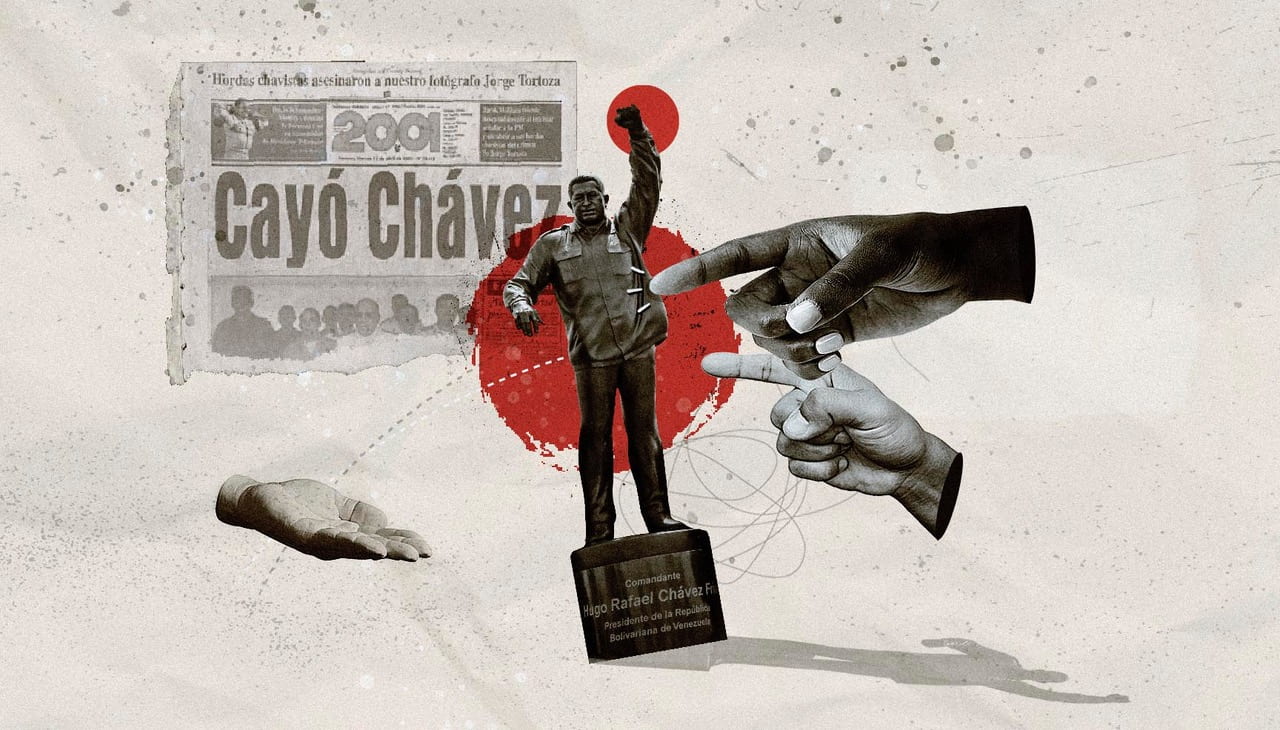

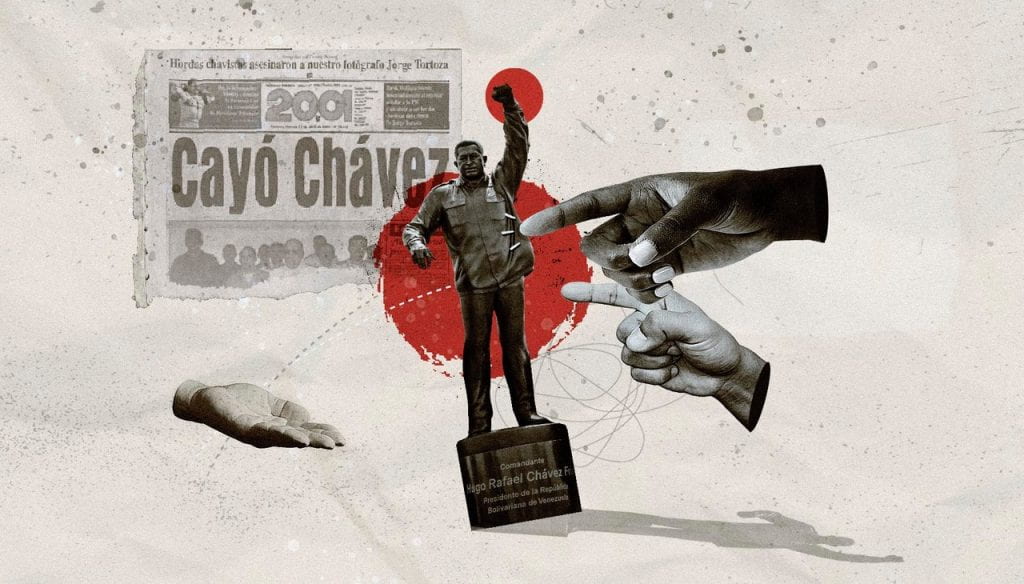

The Statues of Hugo Chávez

Sites of a Contested Legacy

It has been eight years since the death of Hugo Chávez. Given the public knowledge of the former Venezuelan president’s battle with cancer and the speculation stirred up by his absence in the political scene in the months prior to his death, the announcement of his passing on March 5, 2013, was not entirely unexpected. Nonetheless, Chávez’s demise was still shocking and unsettling to most Venezuelans. His opponents, long yearning for a change in Venezuelan politics, were overcome by feelings of hope at the prospect of a political change prompted by Chávez’s death. Supporters mourned the loss of “their giant” whilst grappling with the challenge of how to continue the Bolivarian Revolution without its most prominent figure and architect.

Amid the subsequent uncertainty, one thing did become clear: People were not ready to just let Chávez rest in peace. Particularly noticeable were the efforts of the succeeding government of Nicolás Maduro, which in light of Chávez’s physical absence resorted to a series of commemorative practices to remind his followers—and opponents—of his legacy.

Chávez’s name and political project was (and continues to be) repeated endlessly in the discourse of government officials and supporters. His image is seen on the sides of buildings, on t-shirts, billboards, and murals across the country. Portraits of Chávez hang from the walls of every major public building. His signature has been tattooed on the bodies of fervent supporters and all across the urban landscape, his gaze looks vigilantly upon citizens. Moreover, he has been immortalized in statues that have come to occupy and share spaces in parks and other public places alongside the nation’s historical heroes.

Among all these forms of commemoration, the statues of Chávez erected in Venezuela’s main cities deserve particular attention. Not only are the statues the most imposing and permanent tributes to his legacy, but their fate is also being tested in acts of contestation almost a decade after Chávez’s death, triggered by the deep and intractable social, economic and political crises of the country.

No official records are available about the exact number of Chávez’s statues in Venezuela. However, an investigative piece by the digital news site El estímulo points to the existence of 17 statues and busts distributed across the national territory.

One way of making sense of the Maduro government’s intentions behind erecting statues of Chávez is by reflecting on the discourses of government officials. For example, Diosdado Cabello, vice president of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela and widely considered the country’s second most powerful man, declared in 2016 at the unveiling of one the most well-known statues of the deceased president, “Estamos obligados a hacer este tipo de homenajes porque la derecha insiste en borrarnos al comandante Hugo Chávez de la memoria y ustedes, muchachos más jóvenes, deben tener a Chávez todos los días presente. Deben tener al comandante Chávez como el maestro, como el guía.” [We are forced to pay this kind of tribute because the Right insists on erasing our commander in chief Hugo Chávez from our memory, and you, the younger generation must keep Chávez on your mind every day. You must hold Chávez as your teacher, your guide.]

The 10-foot-high statue in Margarita Island to which Cabello referred, was made of bronze and portrayed Chávez raising one hand and looking to the sky “a la eternidad, a la esperanza de nuestro pueblo”—to eternity, to the hope of our people—, as he had done once during his last end-of-campaign rally in 2012. The statue’s site was purposefully chosen: the 17th Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement was going to be celebrated on the island, and thus representatives from the different countries that comprise the organization would be welcomed by the late president’s powerful image.

As this case makes evident, the erection of statues of Chávez is not an innocent act of commemoration of his persona and political legacy. By their very definition, statues are structures, usually placed in public spaces, that serve to commemorate persons or events deemed important enough to require remembrance. Because statues are erected by governments or figures of authority, they also legitimize the narratives associated with those persons and help create a collective social memory of them. In that sense, statues are politically charged, since the legitimization of certain narratives means that other discourses are silenced.

These basic characteristics already raise some issues about placing statues in public spaces honoring Chávez. To begin with, since statues in Venezuela are usually reserved to and associated with national heroes, by extension, erecting statues of Chávez confers unto him a heroic status—even though a large sector of the Venezuelan population does not consider him as such and instead blame him for the current socio-political and humanitarian crises of the country. Thus, considering that Chávez’s persona incited—and continues to incite—extreme political polarization in Venezuela, statues in his honor contribute to fuel existing political tensions and invite provocation.

Besides helping to create the myth of Hugo Chávez, the statues also serve to assert who controls certain spaces. They act as physical and daily reminders to all who walk past them that although Chávez is dead, chavismo still rules the country. This is particularly relevant when considering the case of the statue in Margarita, which was placed there despite—or perhaps precisely because of—in the weeks before the summit, some of the island’s residents had begun to revolt and had received Maduro with a strong protest during one of his visits. By putting a statue of Chávez in a place that has shown rejection to the government’s ideas, an act of honoring and admiration becomes one of political subjugation.

But perhaps the Maduro’s government’s most exploited and successful use of the iconography of Chávez has been to gain symbolic power for its own political purposes. Drawing on the affection that Chávez inspired in his supporters, Maduro and his government were able to create an illusion of political continuity of leadership, which in turn granted them legitimacy and allowed them to maintain unity during times of political transition. In other words, by using Chávez’s image in its different forms, including statues (or as I have outlined elsewhere, through the use of the images of his eyes in posters, banners and murals in prominent public spaces) the Maduro government was able to link itself with the image of Chávez to enhance its own fragile authority and benefit from the late president’s popularity.

The unexpected effect that Maduro’s government did not foresee, however, was that when its own popularity was put to the test, feelings of rejection were transferred to symbolic icons such as the statues of Chávez. This was evident when, during times of intense protest activity such as the wave of demonstrations in 2017, the statues of the late president became the subject of citizens’ anger, leading to vandalization and destruction.

A noteworthy case was that of the toppling of a statue of the late leader in La Villa del Rosario, a town located in the oil-producing State of Zulia. In a number of videos that went viral on the Internet, it is possible to observe how a group of students participating in a protest set fire to a statue and then pull it down in an act received with cheers by onlookers. Not content with having dismounted the statue, other protesters picked it up and repeatedly smashed it against the ground in an attempt to break it into pieces. This act is not one of a kind: attacks against statues have been repeated on at least 11 occasions in eight other states of the country over the past three years. The statues have been burnt, defaced, mutilated, toppled, and/or hung from bridges, leading to strong military presence surrounding those remaining in order to safeguard their integrity.

These recent acts of contestation not only show that Venezuelans have already reached a breaking point (as newspaper headlines have often suggested). The significance of these events goes beyond the recognition of popular frustration, as they also help us to understand the statues and the spaces they occupy as contested sites in which the narratives of the country’s contemporary history are being forged and challenged. Their erection speaks of the undeniable authority that Chávez represents for a sector of the population and the permanence of his political project in today’s Venezuela. Their toppling and destruction, on the other hand, are a call to challenge a definite and one-sided interpretation of the role of Chávez in the country and at the same time contest the current landscape as inherently chavista. In particular, the act of toppling statues should signal to the government that subjugation through the use of iconography of Chávez no longer seems to be working as a means of controlling its citizens.

As with many things in the country, uncertainty remains about the fate of the spaces that the vanquished statues of Chávez used to occupy. It is difficult to know whether the government is planning to replace them, reconstruct them, or if the pedestals on which Chávez once stood will remain empty for the time being. Personally, I prefer the image of the empty pedestal. Empty pedestals are powerful symbols because they invite reflection. They do not constitute an empty space: The presence of the pedestal reminds us that something once stood there that represented the views of the nation-state, but that it has been challenged or it is in the process of being re-imagined. The empty pedestal can make us rethink our collective memory and practices of memorialization, and lead to an understanding of both as shaped by dynamic forces that are open to interpretation and contestation. Thus, by staying there, empty pedestals such as the ones in which Chávez once stood, can prompt us to question how we memorialize conflicting legacies.

Spring/Summer 2021, Volume XX, Number 3

Jessica Velásquez Urribarrí is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Applied linguistics at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia. Her research focuses on changes in the semiotic landscape of protest in Venezuela, with emphasis on the wave of protest of 2017.

Related Articles

The Eye that Cries: Peru’s Unreconciled Memories

English + Español

In Lima, Peru, in the midst of Campo de Marte, a public park named after the god of war, a Zen space for reflection is guarded by a cast iron fence. El Ojo que Llora (“The Eye that Cries”…

Editor’s Letter: Monuments and Counter-Monuments

Cuba may be the only country on the planet that sports statues of John Lennon and Vladimir Lenin. Uruguay may be the first in planning a full-fledged monument to the victims of the Covid-19 pandemic.

A Monumental Battle for the Story of Texas

In 2016, I visited the Alamo, as part of my first real return to Texas in many years. I had mapped out a road trip with my brother Edmund Roberts. Though Edmund has long known of…