Through a Glass Darkly

Reflecting on Bolivia

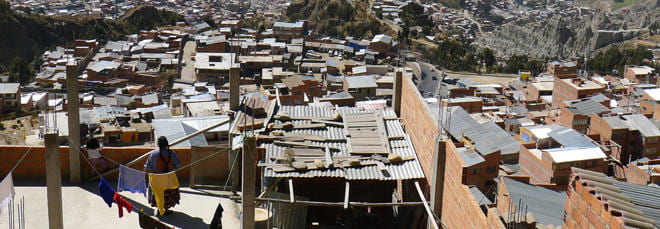

A humble home with red bricks and zinc roofing hovers over the sprawling La Paz skyline. Photo by Winifred Parker

As the American Airlines flight from Miami neared La Paz, we peered down through the thin light of early morning, trying to make sense of the arid land below us. Were the neat pyramids of stones at the corner of each field the result of clearing the land for planting? If so, it must be rocky, inhospitable soil for growing crops. Were those really herds of llamas and alpacas that dotted the landscape? And how spectacular the snow-covered Andes appeared in comparison with the altiplano. We continued to watch as the walled compounds at the edges of El Alto appeared, gaining clarity and detail as we descended to the runway. Before us, Bolivia’s high plains and mountains seemed an exotic moonscape.

Moments later, entering a rustic immigration hall, we took note of the oxygen tanks available for passengers with difficulty breathing at 4,000 meters. Soon, our taxi wove through the early morning throngs of El Alto’s commerce and we descended the sculpted bowl into La Paz. Foot trails bit into the hillsides; shacks clung precariously on dry cliffs along with modern mansions; women in bowler hats and wide, floating skirts trekked downhill, and a river spilled muddy water down a steep sluice. As we entered the city, crowds of indigenous people waited for buses and set up street markets in the shadow of crumbling colonial churches and 19th century buildings recalling the exuberance of periodic economic booms.

Despite the passage of time, our memories of this 1993 arrival are still crystal clear. For both of us, it was a first trip to Bolivia. For one, it was the fulfillment of a lifetime dream to see the Andes and the start of a demanding and unfamiliar assignment. For the other—already well traveled in Latin America—it was the chance to take in the sights and sounds of a new country, to learn firsthand about political, social and economic realities.

This was the first of many visits to a country dramatic in its landscape and its history. Initially, we were pursuing research for a report for the United Nations Development Programme on public sector reform. Within months, however, we were actively engaged in a much larger project involving the Harvard Institute for International Development (HIID) and the Universidad Católica Boliviana (UCB). In this USAID-sponsored initiative, HIID and the university would collaborate to establish a Master’s program in public policy at UCB. We hoped that many of the characteristics of the Harvard Kennedy School, where both of us were teaching, could be adapted to the Bolivian context, contributing to pedagogy and public policy research in this interesting environment.

That program evolved into the Maestrías para el Desarrollo (MpD), the first Master’s program of any kind at a Bolivian university. The MpD has made an important contribution to human capital development for Bolivia’s public, nonprofit and private sectors, training hundreds of students in analytic methods, organizational management and leadership, reaching thousands more through its executive courses and research and consulting work. Setting a standard for postgraduate education in the country, it has consistently demonstrated that scarcity of resources can be compensated through innovation and deep dedication.

Equally important for us, this relationship with the MpD and with a cadre of graduates from the Harvard Kennedy School has been a foundation for enduring friendships with many of the most engaged and articulate citizens of Bolivia. Several of them have written for this important issue of ReVista. Although the original USAID-HIID project is long over, the MpD and the Harvard Kennedy School have continued working together and our history of professional and personal engagement in the country has now spanned almost 18 years. We have vivid memories of that first touchdown in El Alto, for it opened a window on the dramatic history of Bolivia over those years.

Yet we have seen through this window only darkly. The year 1993 was a time of great hope for the country; we saw many problems but we also saw a political and economic landscape that was becoming more stable and secure. Following many years marked by coups and military dictatorships, drug trafficking and corruption and deep economic crisis, Bolivia by then had had a functioning electoral democracy in place for a decade; the military seemed marginalized from political engagement; hyperinflation had been defeated. Successive administrations had introduced policy reforms that aimed to supplant the state-led economy of the preceding decades with a more market-led model of development. Widely touted popular participation reforms gave local communities more resources and decision-making power. The international community eagerly promoted Bolivia’s experience as a model of reform initiatives, and hotel coffee shops in La Paz were bustling with international experts consulting over breakfast and meeting with Bolivian colleagues over generous lunch buffets. It seemed a good time to be introduced to the country’s potential.

What we perceived in 1993 turned out to be untrustworthy, however. Economic growth proved elusive over the following years, especially on the altiplano. Austerity and structural reforms were painful; they required a payoff at some point to be sustainable, and that payoff did not come soon enough for the large population of poor and indigenous people. Many had lost their jobs through economic turmoil and reform; many had been affected by drug enforcement initiatives that threatened their livelihoods and even their customs and values. Many felt betrayed and they denounced neoliberal policies for the hardships they faced. Meanwhile, regional tensions revived when some parts of the country began to grow economically. Neither the political nor the economic reforms had directly addressed the fundamental inequality and injustice in the country’s institutions.

We were not alone in our failure to understand the unresolved issues that Bolivia faced in the mid-1990s. Indeed, the country’s experience turned into a challenge for how economic development was understood and practiced in the 1990s and early 2000s. Some claimed that the reforms had not been deep enough nor fully enough implemented and argued for staying the course; others questioned whether the reforms had been appropriate from the beginning. If stabilization and structural adjustment reforms did not lead to economic growth within a reasonable time period, was a different approach to development needed? If democratic elections and decentralization left so many marginalized from the political process and with little prospect of addressing deep inequalities in the society, how were such issues to be addressed? If drug eradication programs were capable of mobilizing protests from large numbers of poor people, were they the right programs? If regional inequalities increased in the wake of such changes, what needed to be done to ameliorate them? The experience of Bolivia posed these tough questions; it did not, alas, suggest the answers.

A decade after our first visit to Bolivia, we had another opportunity to reflect on the uncertainties involved in understanding current events in a country. The setting, in September 2003, was a dinner party, lively with conversation and excellent Andean food. We were surrounded by friends from the Harvard Kennedy School and the MpD. Many were now professors, while others were serving in government, providing policy analysis and advice to political leaders; two former government ministers were part of the group; others worked in foundations looking for solutions to problems of poverty, poor education, and national identity.

The following day was to be marked by a massive demonstration of indigenous organizations; La Paz would be largely shut down. Thus, much of the discussion at the table concerned serious issues. How should we understand what was happening in the country? How would policy and development issues be decided in the future? How were conflicts about identity and representation to be resolved? The themes were often general: the extent to which neoliberal reforms had opened up space for changing the rules of political engagement or had simply incited anger and protest; the ability of the democratic institutions re-introduced in 1982 to survive tomorrow’s demands for change; the capacity of the government to contain the potential violence of the crowd; the leadership and organization of indigenous protest. But these issues spilled over into more personal questions that underlined the gravity of the immediate situation. Are you going to go to the office tomorrow? Will it be safe to send the kids to school in the morning? Should we stockpile food in case it becomes unsafe to leave the house?

The next day, the two of us stood on the steps of a downtown hotel—thinking that if violence erupted we could easily duck inside—and watched the protest. From this vantage point, it seemed a peaceful demonstration. Rank upon rank of civil and political organizations marched by, each with a banner, the women in indigenous dress and the men in working clothes and jackets, their knitted hats worn as emblems of their cultures. There was little chanting, and we did not feel threatened by the banners or the protesters. We watched for over an hour as thousands passed by, insistently denouncing the government for its management of the economy and the country’s vast natural resources, demanding recognition of distinct cultural identities, claiming power in a new Bolivia, but doing so in well-rehearsed style. This was the first time that we had seen a major demonstration in the cellular era, and we marveled at how order was kept and communications maintained by a small army of marshals with cell phones and walkie-talkies.

In the end, the day ended peacefully, the crowd dispersed, and the government survived. We returned to Cambridge, believing we had witnessed an important event, but fairly sanguine about the capacity of the government to manage such dissent. Two weeks later, however, in the context of growing and increasingly violent opposition, government forces fired on a group of protesters, several were killed, and the president was soon forced to resign and leave the country. A new political era was at hand, one in which the country’s indigenous population would become much more important participants in decisions about the political, economic and social future of the country. Perhaps ironically, or perhaps inevitably, the new democratic institutions introduced in the 1980s and 1990s, if inadequate in themselves, had provided an opening for major political demands for the inclusion of the indigenous peoples of Bolivia into its formal institutions.

These stories—our first impressions of a country and perceptions from a decade later—are unsettling in retrospect. We had probably witnessed far more than we thought we had as our taxi fought against indigenous foot traffic in El Alto in 1993 and as we stood on the steps of a hotel watching a protest in 2003. Should we have been able to “read” these situations more accurately? We were, after all, trained as political scientists, academics who study political processes and work to explain stasis and change in institutional arrangements. At the time, however, we were unable to see clearly into the future or assess the extent to which it would be marked by change.

Indeed, since the early 2000s, the extent of change in Bolivia has been extraordinary. Political, social, and economic issues in the fall of 2011 include questions about the control and use of natural resources, the relationship between central and local governments, the recognition of ancient demands for participation, the right to secede from the nation, and how identity would define political mobilization and voting. A newly written constitution has laid the basis for reshaping political and economic institutions to address some of these fundamental issues, yet turning that document into a set of living, viable institutions will be a long process, and many basic questions remain to be worked out.

Today, we insist that political events such as those that played out in the 2000s in Bolivia reflect prior conflicts over identity, participation, legitimacy and resources. Equally, however, the big steps from 1993 to 2003 to 2011 are a reminder that history is shaped not only over the longer term but also in the shorter term in conflicts about the consolidation of power, how interests are represented and engaged, and how choices are made about the construction of new institutions. While changes may seem foregone conclusions in retrospect, they are anything but certain as energies, strategies, and political resources are put to use in conflicts about power and the direction of development.

As we consider over two decades of change in Bolivia, it now seems to us that understanding history involves adjusting short-term perspectives to longer-term interpretations and, looking backward, seeing through windows more clearly. This is not easily done, and may or may not provide greater insights into the future. As social scientists, we are accustomed to making reference to the enduring nature of institutions and the characteristics of political and social systems, attempting to assess current events in light of continuities and expectations based on what we know of the past. But the day-to-day view from the street is often that of how much change occurs over the short term—and how abruptly it can occur—and of how contingent those changes are.

Certainly Everyman might question the academic view if the recent history of Bolivia is consulted. The 1980s and 1990s had brought many significant changes. But the more fundamental change to come in the 2000s, deeply affecting the country’s political and social institutions and the dynamics of its politics and economic development, could not have been clearly foreseen in those years. There is no question that the Bolivia of 2011 is a very different country from what had existed in those prior decades. Yet the question of how to understand these changes and how to place them in historical context remains elusive.

For many Bolivians who had lived at the margins of politics and economic development for centuries, 2011 is a time of hope again. But many questions remain about the direction and long-term sustainability of economic policies, development strategies, institutional frameworks, and political representation. It is not clear yet whether the balance between hope and disappointment, so often settled on the negative side in the past, will this time sustain the positive expectations of so many Bolivians. The analysis and accounts included in this issue of ReVista may help us understand better some of the aspects of the current situation, the accomplishments, perhaps the failures, and certainly the work remaining to be done. At the street-level, however, we continue to see the future through a glass darkly.

Mary Hilderbrand is a Fellow in Development and director of the Mexico Program at Harvard Kennedy School.

Merilee Grindle is Edward S. Mason Professor of International Development at Harvard Kennedy School and DRCLAS director.

Related Articles

A Review of Alberto Edwards: Profeta de la dictadura en Chile by Rafael Sagredo Baeza

Chile is often cited as a country of strong democratic traditions and institutions. They can be broken, however, as shown by the notorious civil-military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990). And yet, even a cursory view of the nation’s history shows persistent authoritarian tendencies.

A Review of Born in Blood and Fire

The fourth edition of Born in Blood and Fire is a concise yet comprehensive account of the intriguing history of Latin America and will be followed this year by a fifth edition.

A Review of El populismo en América Latina. La pieza que falta para comprender un fenómeno global

In 1946, during a campaign event in Argentina, then-candidate for president Juan Domingo Perón formulated a slogan, “Braden or Perón,” with which he could effectively discredit his opponents and position himself as a defender of national dignity against a foreign power.